One of the most powerful and polarizing people in Oregon history, John McLoughlin championed the Hudson’s Bay Company’s (HBC) business interests in the Pacific Northwest. He was a striking figure, with steel blue-grey eyes, a ruddy complexion, a tall, muscular frame, and shoulder-length white hair. George Simpson, the HBC’s Northern District governor, described him as “a man of strict honour and integrity but a great stickler for rights and privileges,” and one who possessed an “ungovernable Violent temper and turbulent disposition” that frequently led to conflict.

Born on October 19, 1784, in Riviere-du-Loop, Quebec, McLoughlin grew up near the St. Lawrence River in a family riven by Protestant and Catholic conflict. He desired a career in medicine and as a thirteen-year-old apprenticed to a Quebec physician, receiving a license to practice medicine in 1803. Thanks in part to the influence of his uncle, Malcolm Fraser, McLoughlin joined the North West Company that year as surgeon and apprentice clerk.

Following a short-lived relationship with an Ojibwa woman that produced one son, McLoughlin entered into a long-term relationship au façon du pays (in the manner of the country) with Marguerite Waddens McKay in 1810 or 1811, which lasted until his death. By report, McLoughlin was devoted to Marguerite, and she had a cooling effect on his temper. A visiting Anglican minister, Rev. Herbert Beaver, learned the price of questioning the fidelity of their relationship when his description of Marguerite as “a female of notoriously loose character” provoked McLoughlin’s most aggressive act of physical violence—a beating of Beaver in the public courtyard of Fort Vancouver.

McLoughlin’s connection to Oregon began in 1824, three years after the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company merged. HBC appointed him chief factor (head) of the Columbia Department, which ranged from the crest of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. He spent his first four months with Simpson at the department’s headquarters at Fort George, crafting plans to squeeze a profit from the region. McLoughlin’s marching orders were clear: increase profits by reducing dependency on imported European items, initiating a maritime coastal trade, and increasing British presence between the Columbia River and the 49th parallel. He was also to extract as much profit as possible from the region south and east of the Columbia River before it became American.

From Fort Vancouver, soon to become the department’s headquarters and depot, McLoughlin recognized natural resource extraction as key to the HBC’s success. He diversified the HBC’s operations, launching the Oregon Country’s first large-scale agricultural, lumber, and salmon export industries. He established new posts, including Fort Umpqua in west central Oregon, and empowered trapping brigades to extract as many furs as possible south of the Columbia.

Initially, McLoughlin dissuaded retiring HBC employees from homesteading in the Willamette Valley, but by the 1830s he realized that “such a country will not remain long without settlers.” Preferring settlers that he and HBC could influence, McLoughlin nurtured Euroamerican communities in French Prairie.

At first, Simpson lauded the new chief factor and gave him wide authority, but by 1841 McLoughlin’s extension of credit to arriving Americans and the department’s declining revenue troubled him. In meetings in Hawaii, McLoughlin vehemently—and fruitlessly—objected to Simpson’s plans, including the closure of several northern forts and the discontinuation of the fur brigades in Oregon and California. He also deeply resented Simpson’s perfunctory investigation into the 1842 murder of McLoughlin’s son at Fort Stikine.

McLoughlin faced growing opposition from Americans who coveted the HBC’s resources at Fort Vancouver and his land claims in Oregon City. This was punctuated by the Shortess Petition in March 1843, a litany of exaggerated and counterfactual grievances against McLoughlin’s treatment of Americans, signed by sixty-five residents and sent to Congress. He defended his actions to both the HBC and American settlers. “If I had acted Differently to what I have and refused assistance to the first [American] Immigrants,” he wrote, “[Fort] Vancouver would have been taken and the Companys property in it and the Companys Business in the Department Destroyed and for which Robbery and Outrage the Company would never have recovered a farthing.…if I had refused them assistance—they would have starved, the World would have Raised a hue and cry against the company and the succeeding Immigrations would have Eaten the crops the farmers had on hand and they would as a last resource have taken Vancouver.”

In 1845, McLoughlin suggested to the HBC that it hold in his name a recently resolved land claim at Oregon City that included Abernethy Island. He sent drafts on his personal accounts to cover the value of the claim but also ambiguously offered to transfer title, ostensibly to “further the Interests of the Company and Extend British influence.” By including the drafts on his personal accounts, Simpson and the HBC saw an opportunity to remove McLoughlin and accepted his offer to purchase the claim.

The company divided the Columbia Department into multiple districts, reducing McLoughlin’s responsibilities and pay, and replaced his authority with a triumvirate board of management at Fort Vancouver. Simpson and the HBC then placed McLoughlin in checkmate: they offered him the choice of a leave of absence to remain in Oregon—a legal requirement if he meant to hold his claim—or a transfer to a position east of the Rocky Mountains.

McLoughlin’s appeals fell on deaf ears, and he chose to stay in Oregon, accepting a combination of furlough and leave of absence that extended his HBC service on paper to mid-1849. He then focused on constructing a house on his claim, building much of it himself, but the presence of extended family did little to lift his melancholy spirit.

Committed to protecting his land claims and providing financial stability for his family, McLoughlin filed an intention to become a U.S. citizen—and in 1851 became one—but some businessmen continued to challenge him. Eventually, legislation was passed to deprive him of significant property holdings.

After considering a move to California, he remained in Oregon City with his family for the rest of his life. There, he managed his mercantile and milling interests, served briefly as the city’s mayor, and helped provision relief efforts following the murder of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman in 1847. Suffering from numerous ailments, including diabetes, McLoughlin died in his home on September 3, 1857.

American sentiment toward McLoughlin shifted after his death, with many settlers publicizing the support he had provided them. He is remembered through the streets, schools, businesses, and geographic features named for him, including Oregon’s southernmost snow-capped volcano, Mount McLoughlin. His house in Oregon City is preserved today as the McLoughlin House Unit of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

-

![]()

John McLoughlin, c.1850.

Cased photographs collection, Org. Lot 1414, Box 225-A, 0225-A5005, Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Portland, Oregon.

-

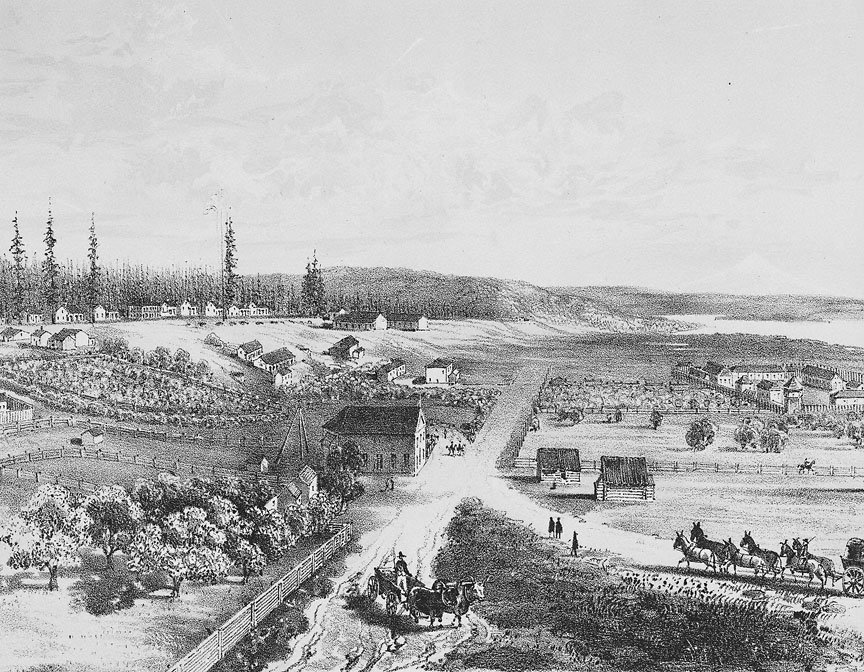

![Sketch by H.J. Warre]()

Fort Vancouver, 1848.

Sketch by H.J. Warre Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi83437

-

![]()

Dr. John McLoughlin.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi73380

-

![]()

Marguerite Wadin/Waddens (McKay) McLoughlin.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi260

-

![This photograph has been tentatively identified as McLoughlin's daughter Eloisa,]()

Eloisa McLoughlin Rae Harvey (?).

This photograph has been tentatively identified as McLoughlin's daughter Eloisa, Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi56638

-

![]()

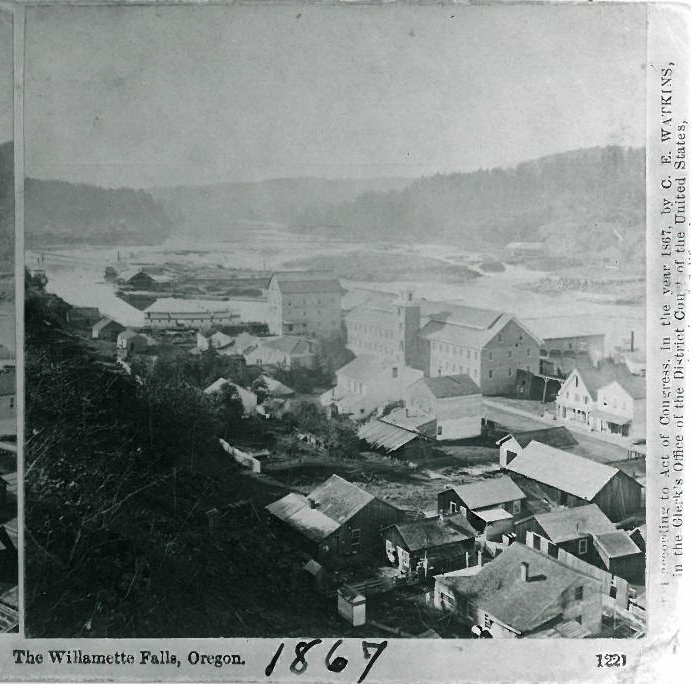

Oregon City, 1867.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., photo by Watkins, 016964

-

![]()

The town of Rufus, 1961.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 006314

-

![]()

McLoughlin in Statuary Hall, D.C..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi11121

-

![Window depicts McLoughlin as a Knight of St. Gregory.]()

Stained glass window, St. John's Church, Oregon City.

Window depicts McLoughlin as a Knight of St. Gregory. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 43249

-

![Sculpted by Adrian Voisin, commissioned by Oregon Congress of Parents and Teachers, located on 99E in Oregon City.]()

Dedication of McLoughlin statue, 1941.

Sculpted by Adrian Voisin, commissioned by Oregon Congress of Parents and Teachers, located on 99E in Oregon City. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![The mural, by Barry Faulkner, is displayed in Oregon capitol building, Salem.]()

McLoughlin meeting with missionaries, mural.

The mural, by Barry Faulkner, is displayed in Oregon capitol building, Salem. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 015824

-

![John and Marguerite were reburied on the corner of Washington and Fifth in Oregon City before being moved a third and final time in 1970 to the relocated McLoughlin House on 7th and Center.]()

Reburial ceremony, 1948.

John and Marguerite were reburied on the corner of Washington and Fifth in Oregon City before being moved a third and final time in 1970 to the relocated McLoughlin House on 7th and Center. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![The church expanded over the graveyard and enshrined the McLoughlins's gravestones in the foundation.]()

John and Marguerite McLoughlin grave sites, St. John Church.

The church expanded over the graveyard and enshrined the McLoughlins's gravestones in the foundation. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![First burial sites on the grounds of the St John the Apostle Catholic Church in Oregon City.]()

John and Marguerite McLoughlin grave sites, 1900.

First burial sites on the grounds of the St John the Apostle Catholic Church in Oregon City. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 21056

-

![The restored home of John and Marguerite McLoughlin.]()

McLoughlin House.

The restored home of John and Marguerite McLoughlin. Courtesy National Park Service

Related Entries

-

![Fort Vancouver]()

Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver, a British fur trading post built in 1824 to optimize th…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

![McLoughlin House Unit of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site]()

McLoughlin House Unit of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site

One of the grandest and most elaborate homes in Oregon when it was buil…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Morrison, Dorothy N. Outpost: John McLoughlin and the Far Northwest. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1999.

Hussey, John A. The History of Fort Vancouver and Its Physical Structure. Portland: Abbott, Kearns, & Bell Co., 1957.

McLoughlin, John. The Letters of John McLoughlin from Fort Vancouver to the Governor and Committee, First Series, 1825-38. Edited by E. E. Rich. Toronto, Canada: The Champlain Society for the Hudson's Bay Record Society, 1941.

McLoughlin, John. The Letters of John McLoughlin from Fort Vancouver to the Governor and Committee, Second Series, 1839-44. Edited by E. E. Rich. Toronto, Canada: The Champlain Society for the Hudson's Bay Record Society, 1943.

John McLoughlin, The Letters of John McLoughlin from Fort Vancouver to the Governor and Committee, Third Series, 1844-46. Edited by E. E. Rich. Toronto, Canada: The Champlain Society for the Hudson's Bay Record Society, 1944.

Gibson, James R. Farming the Frontier: The Agricultural Opening of the Oregon Country, 1786-1846. Seattle: Univ. of Wash. Press, 1986.

Hussey, John A. Champoeg, Place of Transition: A Disputed History. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1967.

Merk, Frederick. Fur Trade and Empire: George Simpson’s Journal. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press, 1968.