Joaquin Miller's early career as a writer illustrates a Biblical truth: “A prophet is not without honor, save in his own country.” Before American audiences paid much attention to him or his work, Miller had to win the buoying salutes of the British literati. Once he was headlined in English sources and became among the first internationally recognized Oregon writers, Miller gained notice among Oregon and California writers and readers and eventually became known as a leader among western Local Color authors.

Born Cincinnatus Hiner Miller to Quaker parents in Indiana in 1837, Miller immigrated west with his family in a covered wagon in 1852. Living near Eugene in the Willamette Valley, he took a few courses at Columbia College before spending two or three years in the mid-1850s in northern California, where Miller lived with a Native woman and fathered a daughter named Cali-Shasta. He returned to Eugene, gained the support of well-known Oregon politician Joseph Lane, and for a few months edited the Democratic Register (also Democratic Review), a pro-Confederate newspaper, until the federal government shut it down. In 1862, he married Theresa Dyer, a writer better known by her pen name Minnie Myrtle. While in Eugene, Miller changed his first name to Joaquin, after the California bandit Joaquin Murietta. By 1864, the couple was in Canyon City, where Miller was elected judge and practiced law.

Miller began his writing career in the late 1860s. Specimens (1868), a collection of poems, and Joaquin, et al. (1869) were self-published in Portland. Neither book benefitted from needed editorial revision or positive newspaper reviews and were largely overlooked in Oregon.

Meanwhile, Miller's marriage was falling apart. On April 4, 1870, Minnie Myrtle sued for divorce, accusing Joaquin of abandoning her and their children. It was a charge that Joaquin never refuted. A divorce was granted about two weeks later. That summer, Miller traveled down to San Francisco. There he met several aspiring California writers, among them Bret Harte, already nationally known for his Local Color stories. Harte praised the Joaquin collection and urged Miller to soldier on as a writer.

In late 1870, Miller visited Scotland, England, and other places in western Europe. His published works continued to roll out with Pacific Poems and Songs of the Sierras, both in 1871. The two books gained attention from English readers and wirters, such as Alfred Lord Tennyson, Christina Rossetti, and Robert Browning, who saw inviting shades of Lord Byron in Miller's romantic works. Perhaps even more influential in Miller's mounting reputation was his presence—his dress, actions, and manner of speaking. To his English peers, Miller became the embodiment of the mythic Wild Westerner, the Far West writer, and the Poet of the Sierras. Like Ernest Hemingway a half-century later, Miller’s presence—his sombrero and cowboy boots and lively activities—shaped opinion about him as much as his writing.

Miller returned briefly to the United States in 1871-72, then sailed back to England. In 1873, Life Amongst the Modocs: Unwritten History was published in London. A retitled Unwritten History: Life Amongst the Modocs appeared the next year in the United States. For Miller, Indians were preservers of the land, and miners were destroyers. The book stirred controversies. Some consider it Miller's most ambitious book, but many readers of the time were not ready to embrace his points of view on those subjects.

After brief stays in New York City and Washington, D.C., in the early 1880s, Miller returned to the West Coast. He had married again, to Abigail Leland, and they had a daughter, Juanita. He settled near Oakland in a spot he named The Hights [sic]. Soon, the carefree pilgrim was again on the road, reporting on the Klondike rush in 1897–1898 and the Boxer Rebellion in China the next year. Then back to Hights, where he remained until his death in 1913. He lived apart from Abigail for most of that period, but they never divorced. They reuinited in 1911, when Miller became seriously ill, and she inherited the rights to his work.

If other Local Color writers such as Bret Harte, Mary Hallock Foote, and Mark Twain were noted for their short stories and novels emphasizing the dress, dialects, and social customs of westerners, Miller did the same in his poetry and some of his poetic prose. He reacted ambivalently to the changes invading and reshaping the West from 1860 to 1910. For the most part, he saw the newcomers as destroyers of the land and other fragile environments and as agents of destruction in mistreating Indians. No one should claim that Joaquin Miller was as influential in showing the molding power of region on character and identity as regionalist writers would soon do, but he proved to be a writer known for his descriptions of western landscapes and westerners going through enormous changes.

-

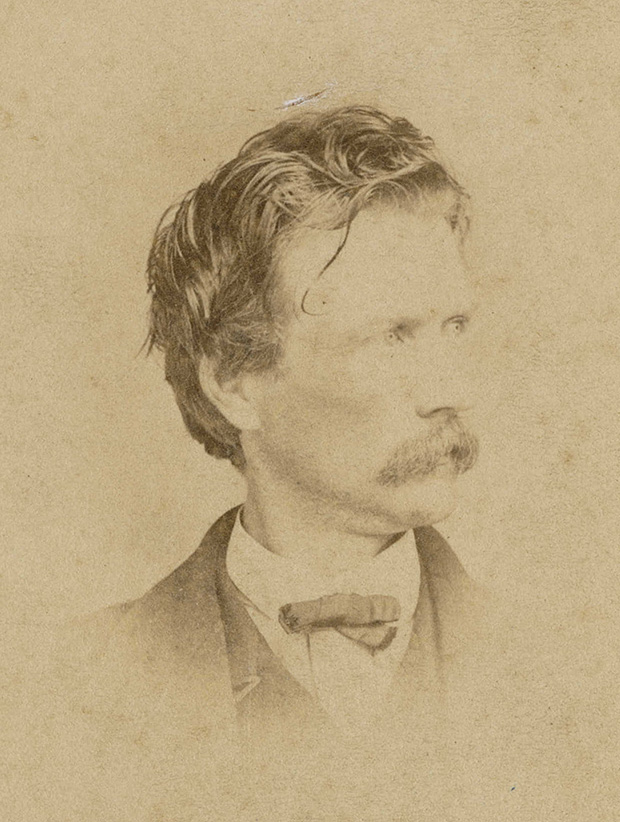

![]()

Joaquin Miller. c. 1868.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrgLot500_A_120 -

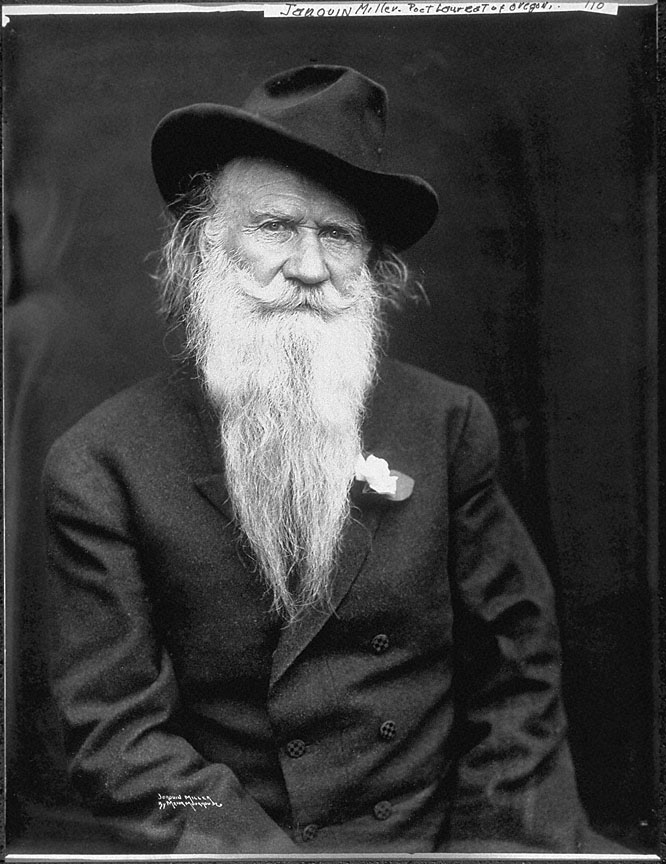

![]()

Joaquin Miller, 1907.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrHi 95226

-

![]()

Capt. O. C. Applegate and Joaquin Miller.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, ba020842 -

![]()

L-R: Phil Metscham, Dr. Edgar Hill, Senator Charles Fulton, Joaquin Miller, and William Steel at Crater Lake, 1903.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, bb000360 -

![]()

Joaquin Miller's cabin, Canyon City.

Courtesy Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives -

![]()

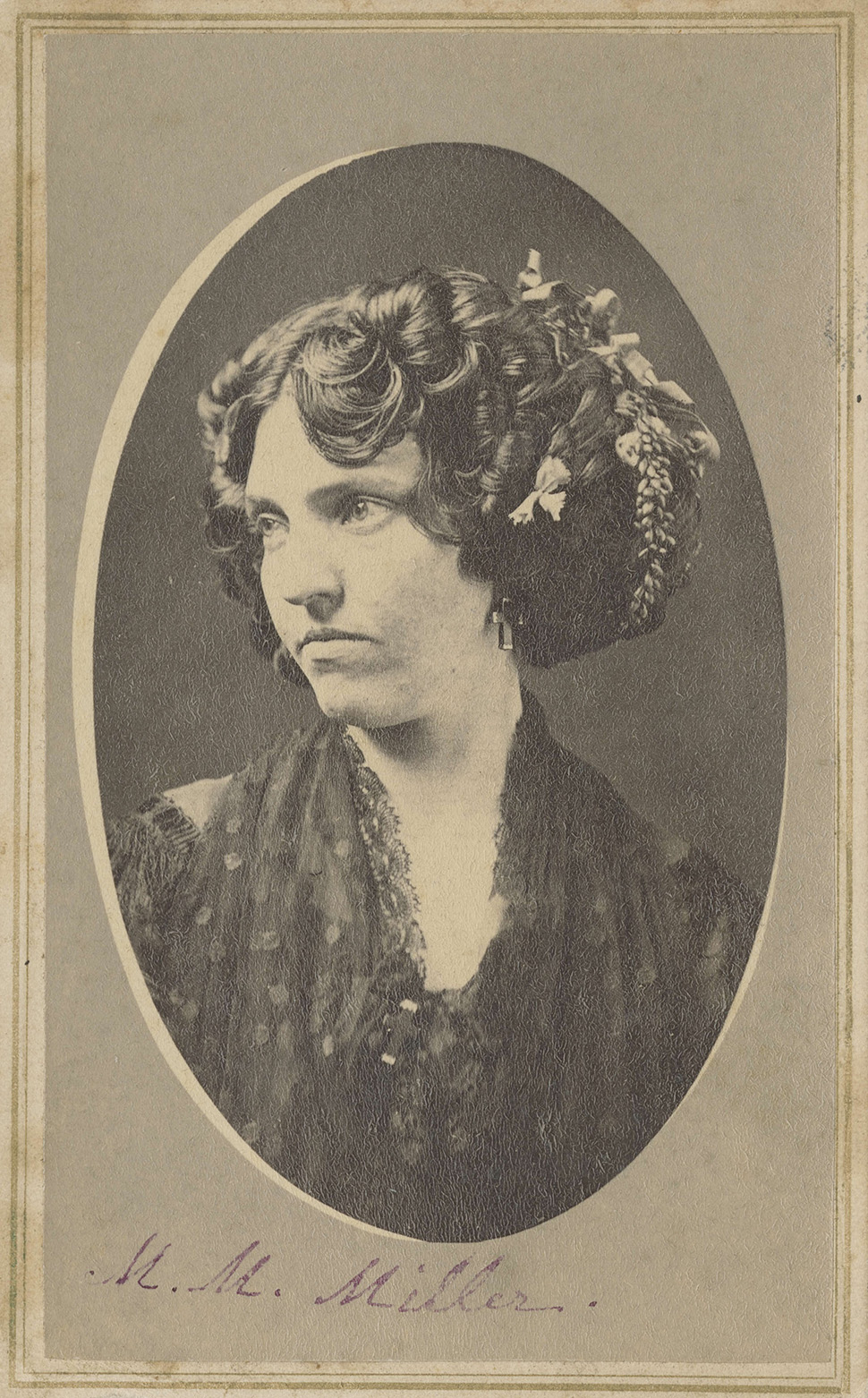

Minnie Myrtle Miller, c. 1870.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrgLot500_A_121 -

![]()

Maud Miller, c. 1873.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrgLot500_A_122

Related Entries

-

![Frances Fuller Victor (1826–1902)]()

Frances Fuller Victor (1826–1902)

In 1869, the Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine featured "Manifest …

-

![Margaret Jewett Smith Bailey (1812-1882)]()

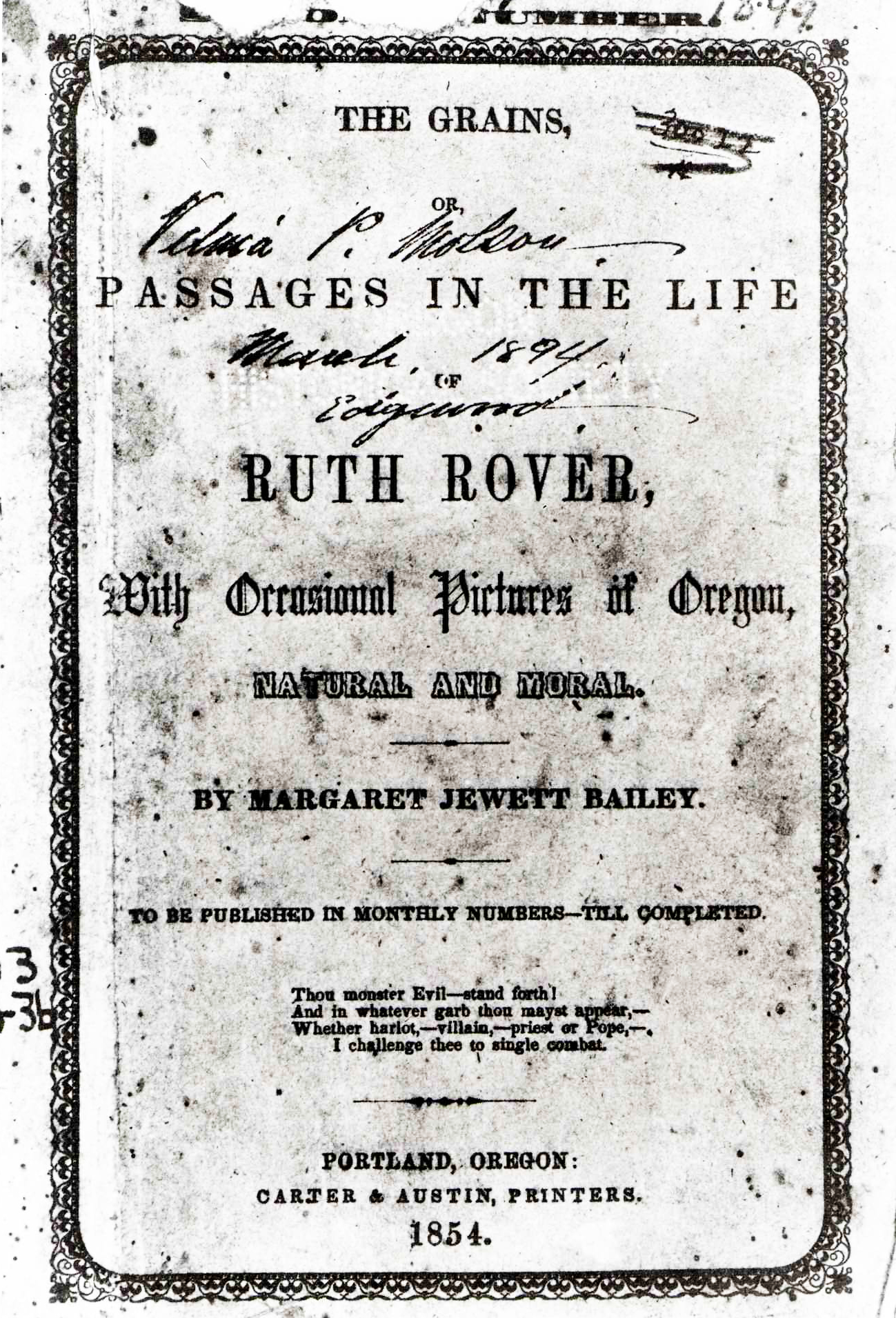

Margaret Jewett Smith Bailey (1812-1882)

Writing under the pen name Ruth Rover, Margaret Jewett Smith Bailey wro…

-

![Minnie Myrtle Miller (Theresa Dyer) (1845-1882)]()

Minnie Myrtle Miller (Theresa Dyer) (1845-1882)

Minnie Myrtle Miller, the "Poetess of the Coquille," was born Theresa D…

-

![Samuel L. Simpson (1845-1899)]()

Samuel L. Simpson (1845-1899)

Sam Simpson was a singer of love songs to Oregon. In 1899, Judge John B…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Frost, O. W. Joaquin Miller. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1967

Powers, Alfred. History of Oregon Literature. Portland, Ore.: Metropolitan Press, 1935.

Rosenus, Alan. "Joaquin Miller (1837-1913)," Fred Erisman and Richard W. Etulain, eds, 303-12. In Fifty Western Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1982.