Hilda Grossman Deutsch Morris was an influential modernist sculptor associated with the Northwest School, a movement of artists that began in the Seattle area in the mid-twentieth century. She exhibited regionally and nationally, maintaining close ties to the New York art world throughout her career. Her sculptures—The Ring of Time (1967), in the Standard Plaza in downtown Portland; Winter Column (1979), at the Portland Art Museum; and Windgate (1980), at Reed College—are important examples of her public work. Throughout her life she stressed a strong conviction that she be regarded as an artist, not as a woman artist in an art world dominated by men.

Born in New York City in 1911, Hilda Grossman studied at the Art Students League of New York and Cooper Union. Her New York upbringing exposed her to sculptors Constantin Brancusi and Reuben Nakian, whose characteristic textural figuration is echoed throughout her sculptures. Her marriage to Arthur Deutsch in 1930 ended in divorce. In 1938, she was hired by the Works Progress Administration, and she moved to Washington State to help establish a sculpture program at the Spokane Art Center, where she taught for two years. While at the Center, she met painters Clyfford Still, Guy Anderson, and Carl Morris, whose contributions to modern art would help connect the Northwest to the epicenter of American modernism in New York. Her time at the Spokane Art Center gave her the connections and institutional support that solidified her artistic development.

Hilda Deutsch and Carl Morris married soon after she arrived in Spokane, and the couple moved to Seattle in 1940. There they befriended Mark Tobey, founder of the Northwest School, who together with Anderson, Still, and Kenneth Callahan helped distinguish the region as a force of American modernism. The Morrises maintained a close correspondence with Tobey, and their discussions about Eastern art and religion and the experience of being in the western landscape greatly affected Hilda Morris’s work. She and Tobey also shared a deep fascination with the mystical symbolism of the written letter. Tobey’s swirling brush lines drew from Eastern calligraphy, while Morris’s roots in Judaism are reflected in the symbolic archetypal references she made through the names of her works and her calligraphic sumi paintings.

In 1941, the Morrises moved to Portland, where Hilda was hired to teach at the Art Museum School (now the Pacific Northwest College of Art). The Vanport flood in 1948 provided salvaged materials for their home and the studio they built in southwest Portland. Hilda taught students and focused on creating art and exhibiting work in galleries and museums.

Both Hilda and Carl Morris were original artists in Arlene Schnitzer’s Fountain Gallery in Portland. During the 1970s, the scale of her sculptures grew, beginning with Mountain Piece (1971), and she became known for her monumental bronze-cast works. Her search for bronze foundries led her to Pietra Santa, Italy, where she worked for part of each year, although Portland remained her home. She also worked in clay, steel/cement, stone, and sumi ink.

Hilda Morris was influenced by abstract expressionism, and as her work matured she moved from quasi-figurative to spontaneous, gestural forms. “Someone asked me what led me to abstraction in sculpture,” she wrote in 1983. “In retrospect, I realize it was the reverse; it was abstraction that led me to sculpture.” Her move toward abstraction was tied to a personal philosophy that emphasized inner strength and human connectedness in relation to the power of organic, rhythmic, and archetypal form. She was influenced by the work of mythologist Joseph Campbell and the ideography of artist Barnett Newman. Poet Carolyn Kizer wrote that Morris’s art is “the bone of legend, the armature on which is strung our sex, our history, our exultant or despairing reach toward imagined places.”

Hilda Morris died at her home in 1991. With over five decades of artistic production, she helped bring national recognition to modern art from the Pacific Northwest. During her life she exhibited nationally and internationally, with exhibitions at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the Smithsonian National Gallery of Art; the Munson William Proctor Institute in Utica, New York; the Seattle Art Museum; the Museo de Arte Moderna in Sao Paolo, Brazil; and the National Museum of Art in Osaka, Japan. At her death, art critic Barry Johnson wrote that Morris “had a quickness of wit, passion for reading and learning and a single mindedness that kept her fixed on her art despite the obstacles women artists faced at the time.” She was honored in 2006 by the Portland Art Museum with a major retrospective exhibition.

-

![]()

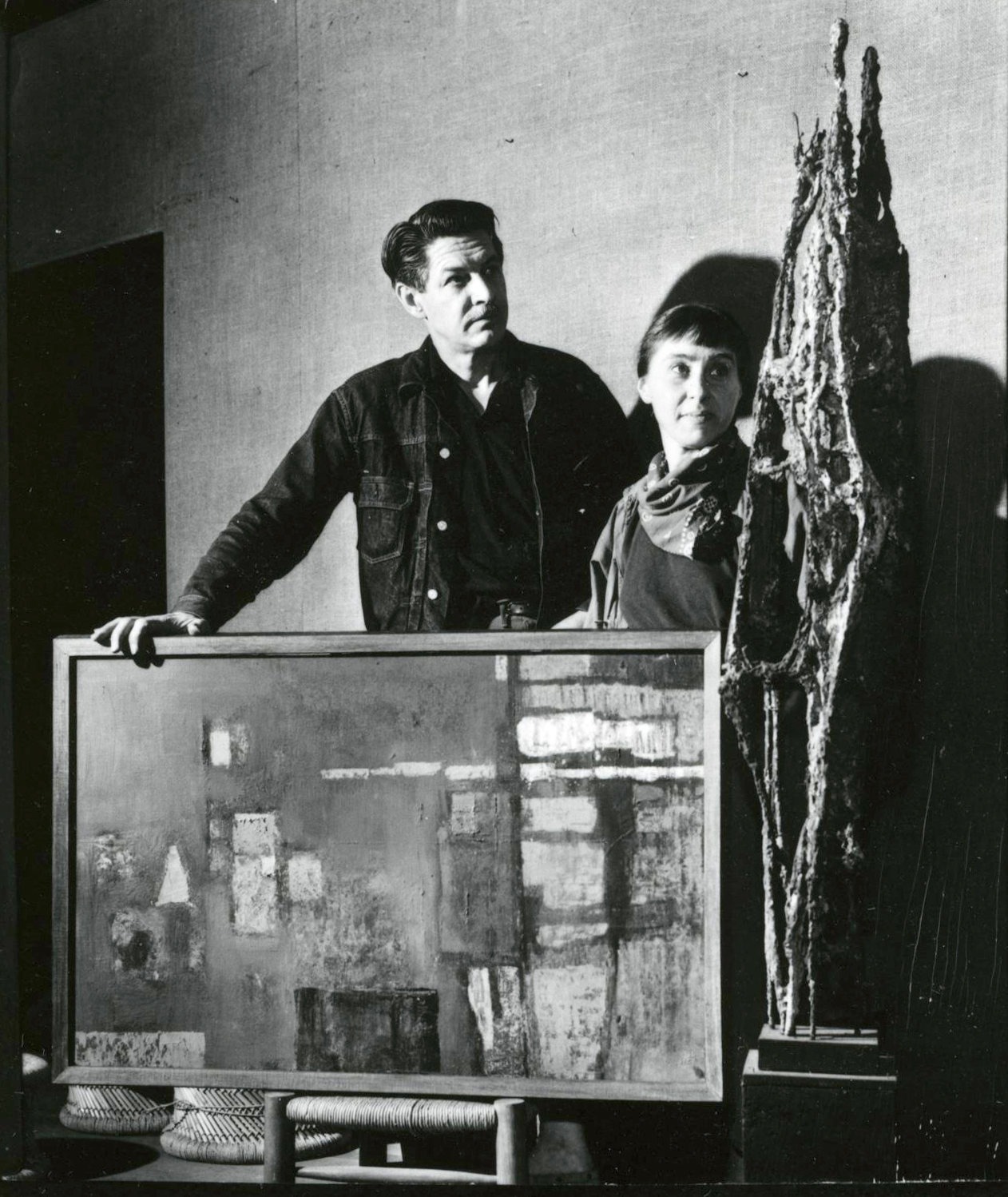

Hilda Morris with her husband Carl in their living room, with paintings, 1959.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 013027

-

![]()

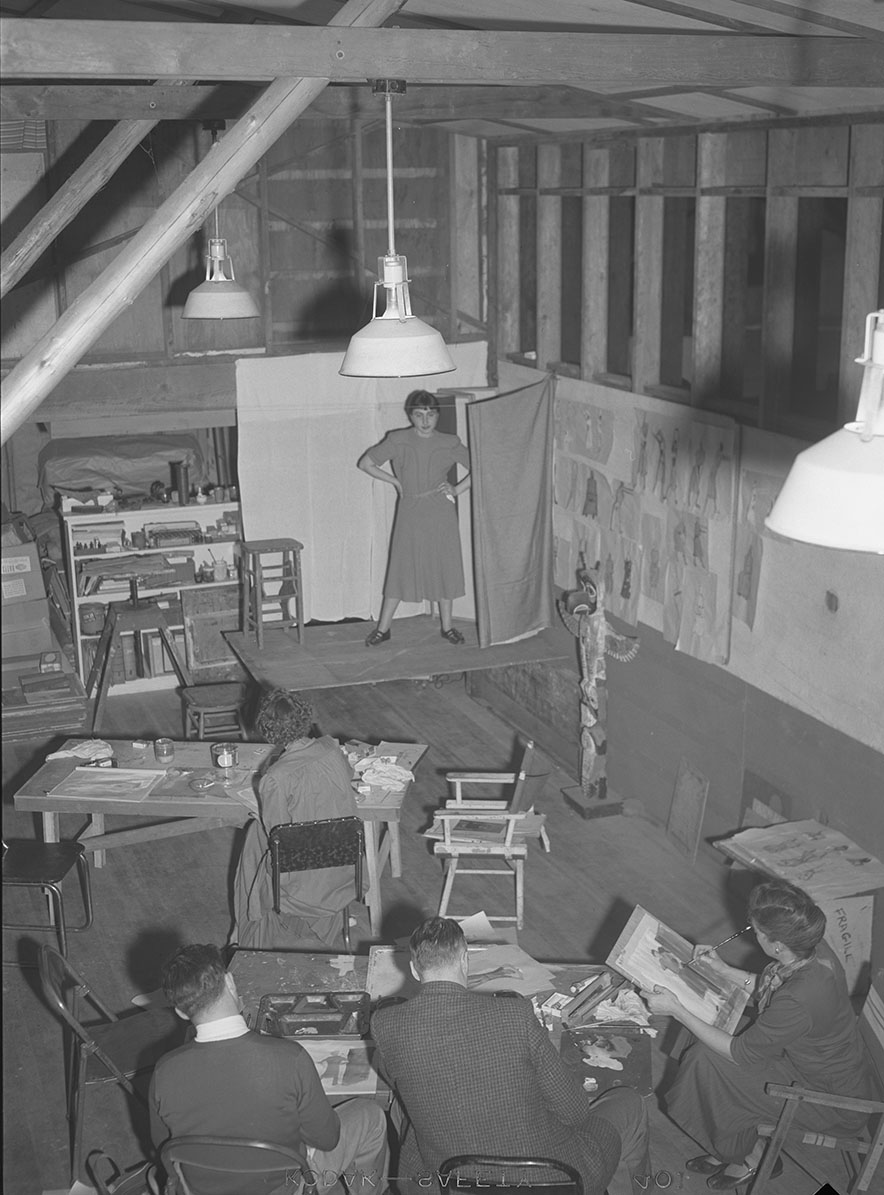

Hilda Morris, 1951.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Al Monner, Org. Lot 1284_1831_1

-

![]()

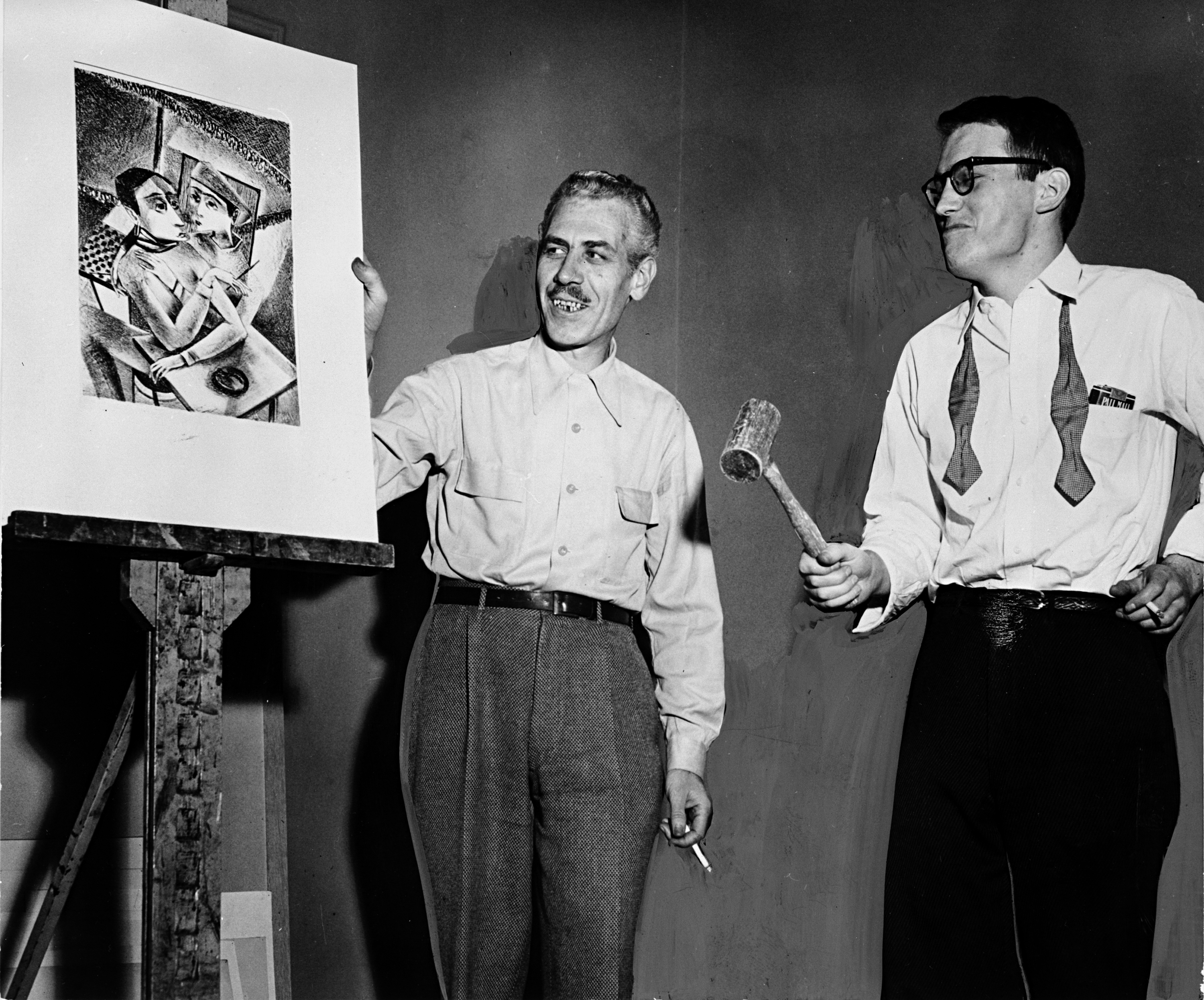

Hilda Morris teaching a class, 1951.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Al Monner, Org. Lot 1284_1831_3

Related Entries

-

![Alexander Phimister Proctor (1860-1950)]()

Alexander Phimister Proctor (1860-1950)

Alexander Phimister Proctor, an American sculptor known for monumental …

-

![Jan Zach (1914–1986)]()

Jan Zach (1914–1986)

Sculptor Jan Zach, who joined the faculty of the University of Oregon i…

-

![Lillian Pitt (1944-)]()

Lillian Pitt (1944-)

Lillian Pitt (Warm Springs, Wasco, and Yakama) was born on the Warm Spr…

-

![Manuel Izquierdo (1925 - 2009)]()

Manuel Izquierdo (1925 - 2009)

Manuel Izquierdo, who arrived in Portland in 1942 as a teenaged refugee…

-

![Mark Sponenburgh (1918-2012)]()

Mark Sponenburgh (1918-2012)

Mark Sponenburgh was an Oregon sculptor, art historian, educator, art c…

-

![Pacific Northwest College of Art]()

Pacific Northwest College of Art

Pacific Northwest College of Art (PNCA), founded in 1909 by the Portlan…

-

![Portland Art Association]()

Portland Art Association

The Portland Art Association (PAA) was organized on December 12, 1892, …

-

![Portland Art Museum]()

Portland Art Museum

The Portland Art Museum, which opened in 1895 in the city library with …

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Filin-Yeh, Susan. “Twists and Surprises.” In Hilda Morris, edited by Bruce Guenther, 41-55. Portland, Ore.: Portland Art Museum and University of Washington Press, 2006.

Griffin, Rachel. “Roots, Rocks, and the Ring of Time: an Interview with Hilda Morris.” Encore Magazine of the Arts 1.4 (January 1977): 6-7.

Guenther, Bruce. “A Stubborn Ambition.” In Hilda Morris, edited by Bruce Guenther, 10-37. Portland, Ore.: Portland Art Museum and University of Washington Press, 2006.

Johnson, Barry. “Remembering.” Artists Trust, A Quarterly Publication (Summer 1991).

Kizer, Carolyn. Hilda Morris: Recent Bronzes. Portland, Ore.: Portland Art Museum; Florence Italy; Centro Di, 1973.

Taylor, Sue. “Morris’s Eye Language.” Art In America (March 2007): 164-166.