Wayne Morse and the Vietnam War: the name and the conflict will be forever linked in American history. Not only did Morse, senator from Oregon, 1945-1969, cast one of the two votes against the 1964 Tonkin Gulf resolution, which gave congressional approval to America's enlarged military involvement in Vietnam, but he also became the Senate's most vocal and persistent critic of the war and those who ran it. With his frequent appearances on television and anti-war speech-making across the country, Morse was rightfully credited for helping turn public opinion in favor of ending the bloody conflict and bringing the troops back home.

It is both fitting and unfair to tie Morse to Vietnam in our collective political memory: fitting because his opposition to the war was so powerful; unfair because that memory tends to eclipse the many other significant accomplishments that characterized an eventful, controversial, and productive lifetime of public service.

Born in Verona, Wisconsin, on October 20, 1900, Wayne Lyman Morse grew up in a struggling farming family steeped in the independent beliefs of Midwestern Progressivism. Morse did his undergraduate work in speech and economics at the University of Wisconsin, from which he graduated in 1923. Upon receiving an M.A. in speech from Wisconsin in 1924, he married his childhood sweetheart, Mildred "Midge" Downie, who would be his companion for life. He then taught speech at the University of Minnesota, where he also earned a law degree in 1928. He began teaching at the University of Oregon Law School in 1929; two years later, at the age of thirty-one, he was named dean, thereby becoming the youngest head of a law school in the nation. With his new status, he led a successful statewide effort to defeat the infamous Zorn-McPherson bill, an initiative intended to dissolve the University of Oregon by combining it with Oregon State College (later Oregon State University) under one roof in Corvallis.

In the late-1930s, Morse, while still serving as Law School dean, acted as a labor mediator on the Pacific waterfront. He was in heavy demand up and down the West Coast by both shippers and dockworkers, so much so that parties on either side often refused to negotiate unless Dean Morse agreed to arbitrate their contract. One magazine labeled him "Boss of the Waterfront." Also during the 1930s, Midge gave birth to three daughters, Nancy, Judith and Amy.

Morse caught the eye of the Roosevelt administration, which employed him first to head a study for the Justice Department, then to settle a nationwide railroad strike, and finally, in 1942, to be a member of the National War Labor Board, a role in which he distinguished himself by writing three times the number of opinions on wartime labor-management grievances than produced by the other eleven members of the board combined.

Morse entered politics in 1944 and in his very first race won a seat in the U.S. Senate. Though elected as a Republican, he announced, in the language of the maverick, that he was "going to serve as my own master, under obligation to no one." That he would follow the maverick's way and not the path of party fidelity became evident almost immediately: he offered his own views on nearly every issue that came before Congress, from atomic weapons secrecy to parking regulations in the District of Columbia. More often than not—two-thirds of the time—he voted with the opposition Democrats. Morse was reelected in 1950 by one of the widest margins in Oregon history. Earlier that year he, along with six other senators, signed a Declaration of Conscience condemning the tactics used in congressional anti-Communist "witch hunts."

Morse broke party ranks entirely in 1952, angrily refusing to support the Eisenhower-Nixon ticket, whose platform he believed had been hijacked by reactionary elements of the Republican leadership. He declared himself an independent, campaigned vigorously for Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson, and went on to serve in the Senate as a one-man "Independent party" for the next two-and-a-half years. During this period, he attracted national attention by speaking—on his feet, without leaving the Senate floor—for twenty-two hours and twenty-six minutes in a record-setting filibuster against the government's attempt to weaken public control over off-shore oil deposits.

Morse was reelected as a Democrat in 1956, soundly defeating Secretary of the Interior and former Oregon governor Douglas McKay. His popularity could be attributed, in part, to the record he had made in fostering the state's all-important timber industry: a record based on promoting sustained-yield logging and marketing opportunities for the smaller-sized forest-products companies. One of his first acts in the new Congress was to cast the deciding vote that gave the Democrats—and their majority leader, Lyndon Johnson—control of the Senate. This led to a restoration of his senatorial seniority, lost when he bolted the Republican Party. Thus Morse became an influential member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and especially of the Labor and Public Welfare Committee, where he was named chairman of the powerful Subcommittee on Education.

For much of his previous legislative career, Morse had been seen as a fearless and oft-times contentious defender of the positions he believed in, and his attacks sometimes turned opponents of the moment into lasting enemies. But as chair of the Education Subcommittee, working to advance John F. Kennedy's New Frontier and Johnson's Great Society programs, he was a master of consensus-building. He was described by a former adversary as "a man of high integrity . . . fair, open-minded, honest, and reliable." So regarded, he led a revolution in federal education policy, spearheading the passage of nearly sixty pieces of legislation, covering everything from the Head Start and Teacher Corps experiments to acts that revitalized teaching institutions, from pre-school to university, throughout the country. He came to be known as "Mr. Education" by his congressional colleagues.

In 1962, Morse was reelected by a convincing fifty-four percent of the vote. Four years later, in Oregon's 1966 senatorial race, he broke ranks again, this time by backing a Republican, Governor Mark O. Hatfield, a dove on Vietnam, against a Democratic candidate who was a staunch defender of the administration's war policy. Many Democratic activists would not forgive him for this apostasy and did little to help him in 1968 in his bid for a fifth term in the Senate. Morse lost to Republican Bob Packwood in a very tight contest. In a comeback attempt, he ran unsuccessfully against Hatfield in 1972. Morse died suddenly on July 22, 1974, in the midst of a vigorous campaign to reclaim his seat from Senator Packwood.

If admiration of a political figure can be measured by the number of posthumous tributes in his name, then admiration for Morse, especially by hometown friends and followers in Eugene, is close to limitless. The Morse ranch in Eugene has been turned into a city park, administered by the Wayne Morse Historical Park Corporation. The University of Oregon offers studies in the Wayne Morse Center for Law and Politics. There is a Wayne L. Morse Federal Courthouse and a Wayne Morse Free Speech Plaza in downtown Eugene. And perhaps of most significance, the Morse Historical Park Corporation issues an annual Integrity in Politics award to a national figure who, in its estimation, best follows Senator Morse's personal credo: "Principle Over Politics."

-

![Wayne Morse]()

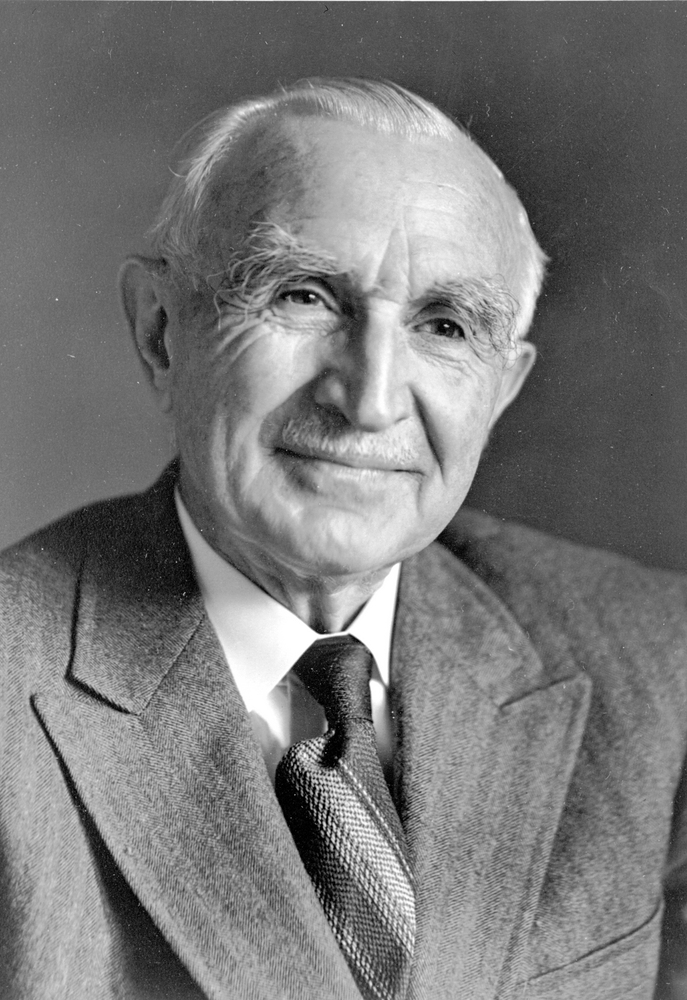

Wayne Morse.

Wayne Morse Oregon Historical Society Research Library OrHi 73854

-

![]()

Wayne Morse.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library OrHi 73858

-

![]()

Wayne Morse.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library CN 013763

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Drukman, Mason. Wayne Morse: A political biography. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1997.