The first forest reserves in the state were established in 1892-1893, although management of the federal forests did not begin until the summer of 1898. The origin of the Cascade Range Forest Reserve dates from the summer of 1885, after William G. Steel visited Crater Lake near the southern end of the 300-mile Cascade Range. Steel stopped in Salem to meet with Judge John B. Waldo, who suggested that federal protection for the entire Cascade Range was needed. Steel began with the effort to make Crater Lake into a national park.

On February 1, 1886, Pres. Grover Cleveland, by executive order, suspended homesteading in ten townships around Crater Lake and northward to encompass the Diamond Lake area. It was the first withdrawal of public land in Oregon for scenic or forestry purposes. Congress would establish Crater Lake National Park in 1902.

Waldo and Steel led an effort to obtain a much larger forest reserve along the crest of the Oregon Cascade Range. In early 1891, Congress was reconsidering provisions in the nation's land laws. An amendment (Section 24) attached to the legislation would allow the president to establish forest reserves. The act, signed on March 3, 1891, was later referred to as the Creative Act or the Forest Reserve Act.

First Forest Reserves in Oregon

The first attempt to use the law in Oregon was by the City of Portland. In the early 1890s, Henry Failing, chair of the Portland Water Commission, asked that a forest reserve be created around the new municipal watershed. The Bull Run Timberland Reserve, covering 142,080 acres, was established by presidential proclamation on June 17, 1892. It was the first forest reserve in Oregon.

The second forest reserve in the state was established in the fall of 1893 to protect the City of Ashland’s watershed. The Ashland Forest Reserve, which set aside 18,560 acres, was established on September 28, 1893. The Cascade Range Forest Reserve was created on the same day. Whereas the other reserves were small in size, the Cascade Range Forest Reserve encompassed 4,492,800 acres and was 235 miles in length, the largest forest reserve in the nation.

Petitions to dismantle the reserve came in 1895-1896. The protests came from sheep owners in north-central Oregon, a few homesteaders in or near the reserve, and miners in the Bohemia Mining District. The entire Oregon congressional delegation was ready to eliminate or severely reduce the Cascade Range Forest Reserve until William Steel spent several months in Washington, D.C., persuading the president and bureaucrats to keep the reserve intact. Meanwhile, Waldo and others from the Mazamas, an Oregon mountaineering group, kept up a steady letter, petition, and telegram campaign to the president, Congress, and the General Land Office. By the late spring of 1896, their combined efforts were successful in keeping the reserve intact.

The large Cascade Range Forest Reserve was eventually split into the Oregon (now Mount Hood), Cascade (now Willamette), Umpqua, and Crater (now Rogue River-Siskiyou) National Forests on July 1, 1908. Another division followed three years later when the Santiam National Forest was carved from portions of the Oregon and Cascade National Forests. On the same day, the land area east of the crest of the Cascade Range was given to the new Deschutes and Paulina National Forests. The Cascade National Forest name disappeared as a distinct entity in 1933 when it was combined with the Santiam National Forest to form the Willamette National Forest.

From 1893 to 1897, no additional forest reserves were established in Oregon or elsewhere in the country. Pres. Cleveland was awaiting action by Congress to pass legislation that would authorize the investigation and management of these federal forests.

Washington's Birthday Reserves

Meanwhile, efforts were underway in Congress to change the procedures for establishing federal forests. The National Forest Commission, funded by Congress through the National Academy of Sciences, was sent in 1896 to investigate the forest reserve situation in the West. William Steel was invited to guide the commission through the Oregon mountains. After the commission left Crater Lake, they traveled to the Sierras in California, then to southern California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado before returning to Oregon. John Muir accompanied the commission as an unpaid member.

The commission proposed that thirteen new forest reserves be created or expanded across the nation, totaling 21,378,840 acres. On February 22, 1897, Cleveland issued the proclamations that were afterward known as the Washington's Birthday Reserves. None of them were in Oregon.

Many people were in favor of the forest reserves, but their voices were barely heard over opponents’ letters to editors, Congress, and the president. Nevertheless, the Forest Management Act was signed into law on June 4, 1897; it is often referred to as the Organic Act of 1897. One of the clauses in the act provided that any new reserves would have to improve and protect the forest, secure favorable conditions for water flows, and furnish a continuous supply of timber. The act established the basis for federal forest management for the next sixty-three years.

In the summer of 1897, the General Land Office in the Department of the Interior appointed superintendents for each state where there were forest reserves. By the next year, supervisors had been appointed and forest rangers had been assigned to patrol the reserves during the dry summer months. On February 1, 1905, responsibility for the forest reserves was transferred to the Department of Agriculture, where they were managed by Gifford Pinchot, head of the newly created U.S. Forest Service.

Land Frauds in Oregon

Another provision of the Organic Act was the Forest Lieu clause, which allowed homesteaders within the proclaimed forest reserve boundary to exchange their claims for public domain land outside the boundary. The provision would lead to massive land frauds in Oregon.

Stephen A. Douglas Puter, the self-proclaimed "king of the Oregon land fraud ring," wrote Looters of the Public Domain in 1907 while serving time in the Multnomah County jail. His insider account of defrauding the U.S. government provided names, dates, and dollar amounts and described the actions of many land speculators in the state.

Puter testified against his friends in the Oregon Land Fraud Trials, including state representative Binger Hermann and U.S. senator John H. Mitchell from Oregon. Mitchell was indicted, tried in a sensational trial that lasted for several months, convicted of fraud on July 3, 1905, and sentenced to six months in jail. He died of complications following a tooth extraction on December 8, 1905, while his conviction was under appeal.

Hermann, who was dismissed from his post by Pres. Roosevelt in early 1903 for trying to cover up his involvement in the frauds, was indicted for his role in the Blue Mountains Forest Reserve case. He went to trial in January 1910, but because the prosecution had difficulty proving his direct involvement in the land frauds, the jury was deadlocked and Hermann was set free. He had avoided conviction by destroying key General Land Office files and letters while he was still in office. It was the last of the big land fraud trials in Oregon.

Meanwhile, Roosevelt continued to make proclamations creating new forest reserves and enlarging existing ones. Between 1904 and 1906, ten new forest reserves were established in Oregon: Baker City (1904), Blue Mountains (1906), Chesnimnus (1905), Fremont (1906), Goose Lake (1906), Heppner (1906), Maury Mountain (1905), Siskiyou (1906), Wallowa (1905), and Wenaha (1905).

Soon thereafter, U.S. senator Charles W. Fulton of Oregon introduced an amendment to a bill that would eliminate the president's authority to establish national forests in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. Only Congress would be allowed to establish forest reserves in those states. The amendment also changed the name of the forest reserves to national forests in order to make it clear that the forests were to be used, not preserved.

With less than a month before the act would be signed into law on March 4, 1907, Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot and his assistants drew new forest reserves on a map of the United States. As soon as the maps were finished and proclamations written, the documents were carried to Roosevelt, who signed each proclamation. Within a few days, the president proclaimed over 16 million acres of new reserves, afterwards known as the "Midnight Reserves." Opponents to the forest reserves were furious, but they were outflanked. Five new national forests were proclaimed in Oregon: Blue Mountains National Forest (added to the older Maury Mountain Forest Reserve), Coquille National Forest, Imnaha National Forest (created from the older Wallowa and Chesnimnus Forest Reserves), Tillamook National Forest, and Umpqua National Forest (Coast Range).

The creation of these new national forests established the foundation for the national forest system in Oregon as we know it. Many changes have been made in the names and boundaries of the national forests, but the basic land areas that were set aside between 1892 and 1907 are still with us today.

Management of Forest Reserves and National Forests

Congress transferred all forest reserves and their management to the Department of Agriculture on February 1, 1905. The United States Forest Service (USFS) was created on July 1 by making a simple name change from the Bureau of Forestry. After late 1904, Forest Service employees were hired through the Civil Service Commission rather than by political appointment, as they were under Department of the Interior management.

Probably the most difficult part of the Civil Service ranger exam was properly tying a diamond hitch to hold boxes on a horse or mule. In some exams, a candidate was required to cook a meal over an open fire, then eat it. On passing the exam, the new rangers were issued uniforms, a bronze badge, and the Use Book (a small volume of 142 pages that contained all the laws and rules for management of the national forests). The Forest Service shield, as it is referred to, was printed on all agency publications and signs and was used for the identification of Forest Service vehicles.

Thousands of hours were spent surveying forest boundaries, mapping them, and posting USFS property signs. In some cases, rangers could rely on old USGS survey maps and notes, but the job was difficult in more remote locations where there were no adjacent land surveys, much less township, range, and section lines and marked corners.

The ground level of the Forest Service is comprised of the ranger districts, which were organized around grazing units. By the 1920s, many old grazing units were combined into one or more ranger districts. When the first ranger stations were built, they were usually located along main trails or adjacent to lakes and rivers. The early rangers, who often traveled by horseback, used the stations to get out of inclement weather. If rangers were fortunate, they used old homestead cabins that had been converted into ranger stations, but most early stations were nothing more than shelters without windows, doors, or even floors. For years, the USFS raged a battle with Congress over the amount of money spent on building ranger stations, and many stations were not built or improved until the 1930s, when the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was created.

Within a few years, the USFS added new categories of forest rangers, including assistant rangers, forest guards, forest assistants, forest examiners, forest clerks, protective assistants, junior forest rangers, and district rangers. In the early days, the forest rangers earned between $900 and $1,500 a year. Rangers in the field—as most were—had to provide most of their own equipment, including horses, pack animals, saddles, shovels, axes, food, and sleeping materials.

In 1911, the Weeks Act allowed the Forest Service to support fire suppression activities in federal, state, and private forestlands. In the aftermath of the 1910 fires in Montana and Idaho, the Forest Service made fighting fires on the national forests the most important aspect of management. It was not until the CCC was established in the 1930s, however, that there were enough fire fighters available to fight fires and stop them from spreading.

The Forest Service set liberal timber harvest policies in Oregon during the first three decades of the twentieth century. In eastern and central Oregon, auction sales of the sizable old-growth pine stands supported expanding forest industries in Bend and Burns. Increasing timber cutting from the national forests on the west side became standard in the 1920s and early 1930s, although the Depression curtailed much of the harvest activities. The Forest Service also preserved forest stands, including the protection of watersheds supplying clean water to the cities of Portland and Ashland.

By the time of the Great Depression, USFS management of Oregon's federal forestland had established a regimen that protected forest resources, encouraged industrial forestry, and created special preserves. Demand for timber remained depressed in Oregon through the 1930s. The era of increased timber harvest off federal forests in Oregon would not begin until the early years of World War II, when a new phase in the history of the U.S. Forest Service in Oregon began.

-

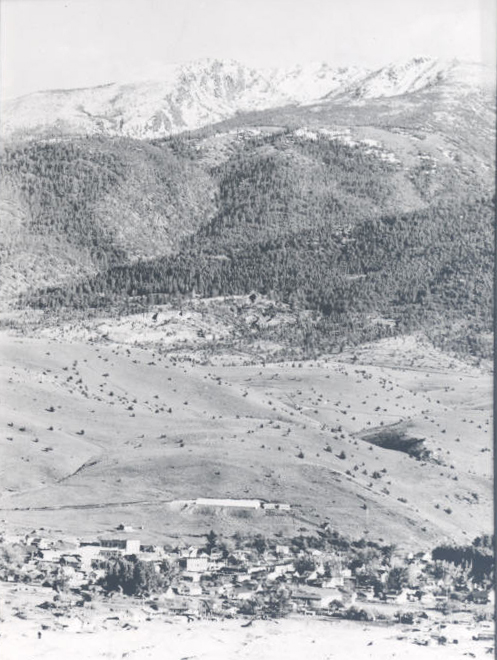

![Siskiyou National Forest]()

Siskiyou National Forest.

Siskiyou National Forest Courtesy United States Forest Service

-

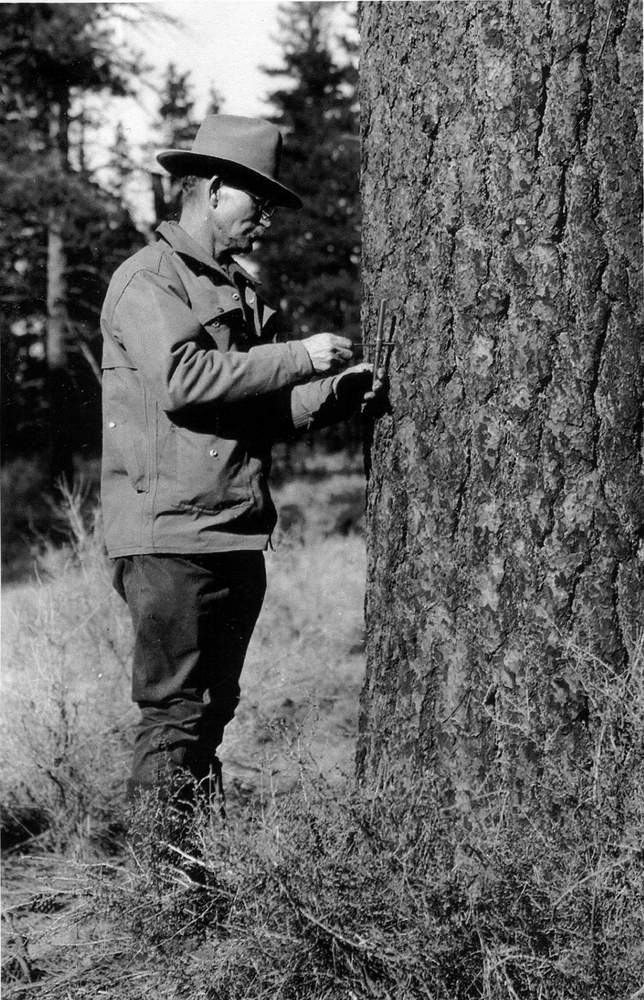

![Forest Ranger Loren J. Cooper, ca.1930s .]()

Forest Ranger Loren J. Cooper, ca.1930s. .

Forest Ranger Loren J. Cooper, ca.1930s . Courtesy Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest

Related Entries

-

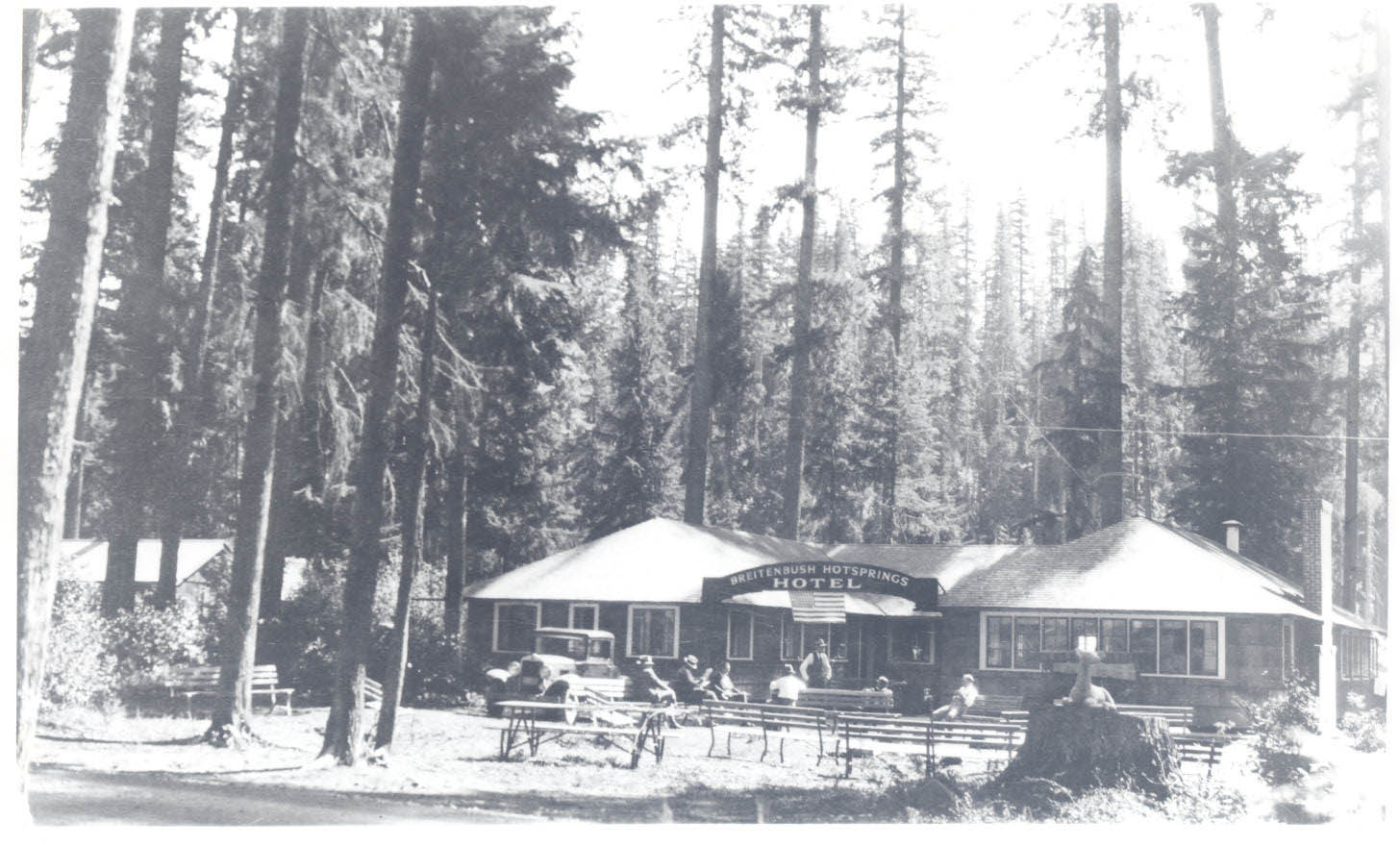

![Breitenbush Hot Springs]()

Breitenbush Hot Springs

Nestled in the northern tip of the Willamette National Forest, about si…

-

![Company Towns]()

Company Towns

While there have been scores of industrial settlements and communities …

-

![David T. Mason (1883-1973)]()

David T. Mason (1883-1973)

David T. Mason was a professional forester, one of the first in Oregon.…

-

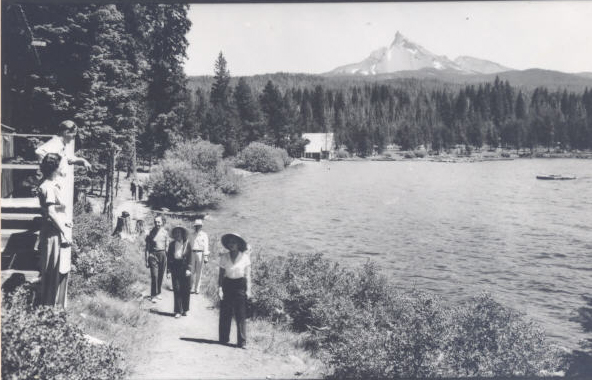

![Diamond Lake]()

Diamond Lake

“Gem of the Cascades” is how Diamond Lake is heralded by those who trou…

-

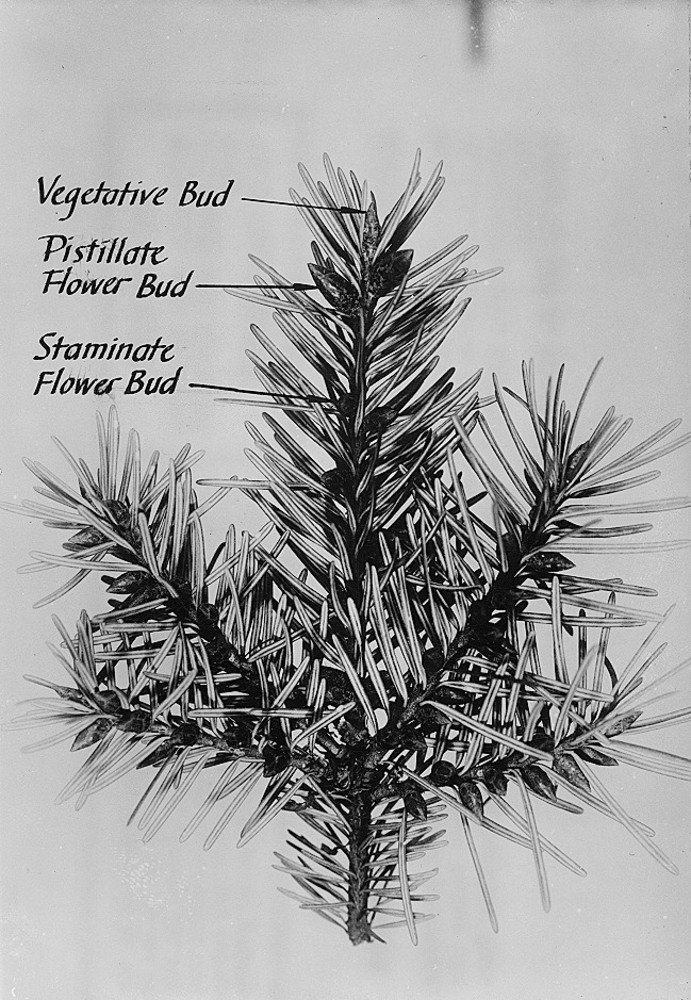

![Douglas-fir]()

Douglas-fir

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), perhaps the most common tree in Or…

-

![Elk Lake Guard Station]()

Elk Lake Guard Station

In 1920, when a wagon road connected Bend with Elk Lake thirty-five mil…

-

![Forest Fires of 1910]()

Forest Fires of 1910

During the late summer of 1910, a searing drought combined with high-ve…

-

Forest Service Radio Lab

The Forest Service Radio Laboratory (FSRL)—located in Portland from 193…

-

![Gilchrist]()

Gilchrist

Gilchrist, in northern Klamath County, located along U.S. Highway 97 ab…

-

![Henry Haefner (1884-1980)]()

Henry Haefner (1884-1980)

Henry Haefner was an early forester and oral historian in the Siskiyou …

-

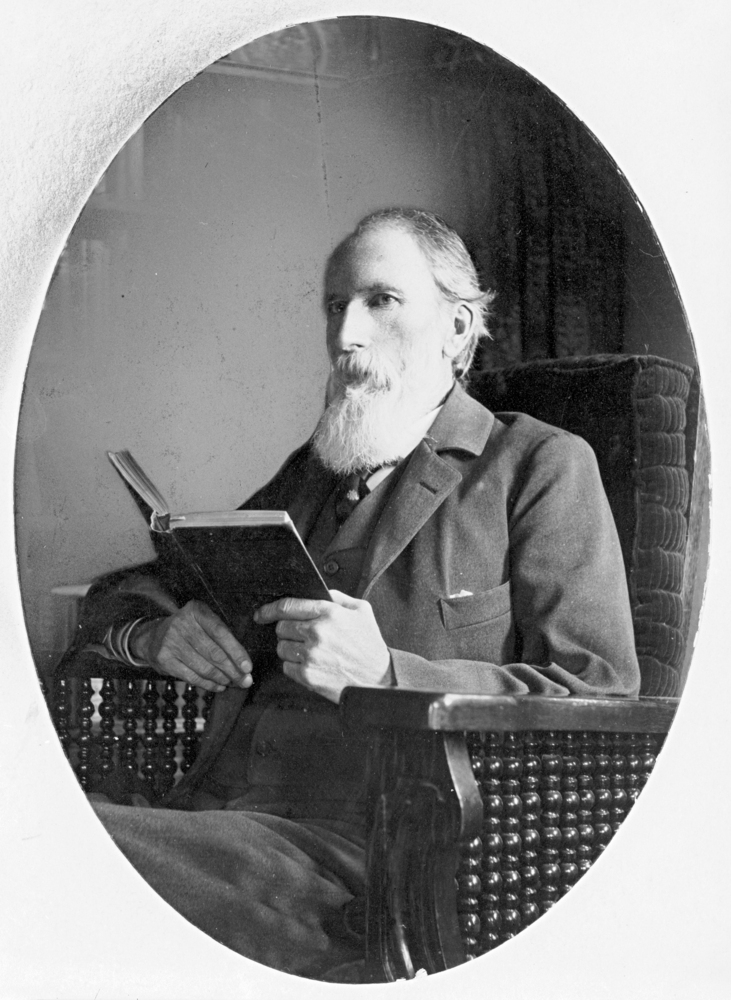

![John B. Waldo (1844-1907)]()

John B. Waldo (1844-1907)

John Breckenridge Waldo was the first Oregon Supreme Court chief justic…

-

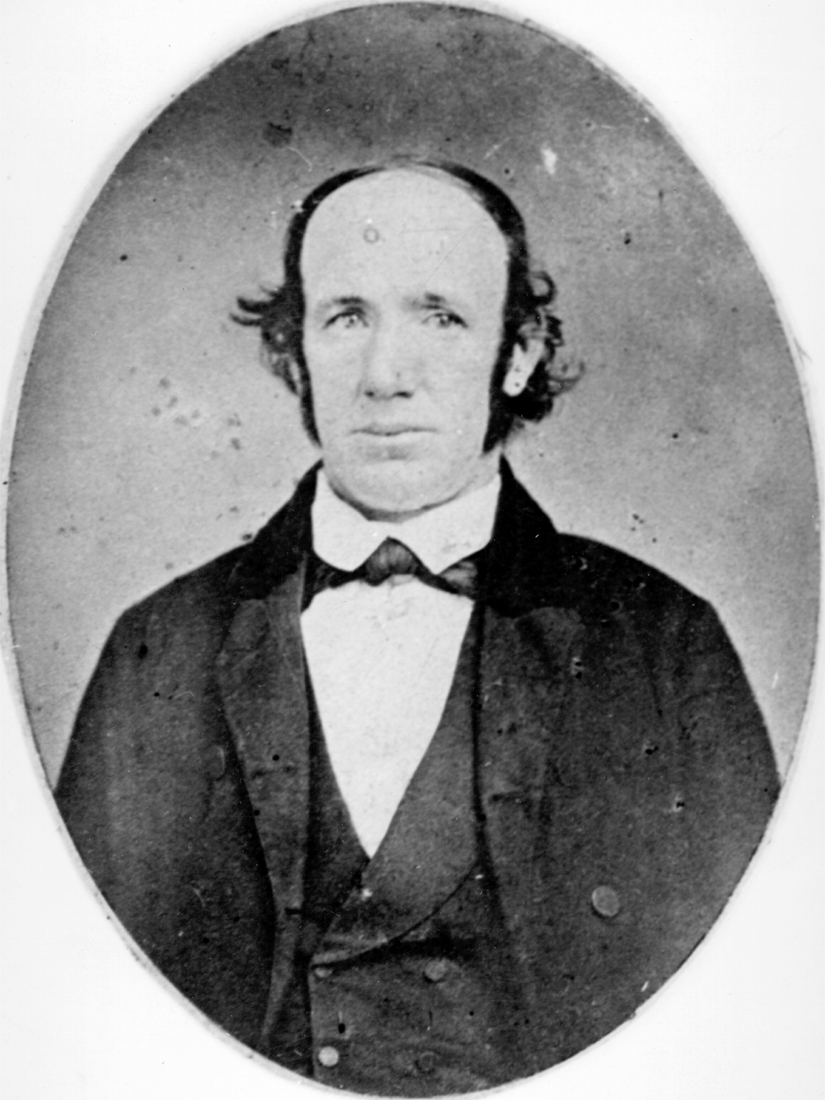

![John Minto (1822-1915)]()

John Minto (1822-1915)

John Minto described his sudden decision in 1844 to strike out for Oreg…

-

![Kalmiopsis Wilderness]()

Kalmiopsis Wilderness

The 179,850-acre Kalmiopsis Wilderness, located in southwestern Oregon …

-

![Oregon Land Fraud Trials (1904-1910)]()

Oregon Land Fraud Trials (1904-1910)

During the summer of 1905, while visitors enjoyed the amusements of the…

-

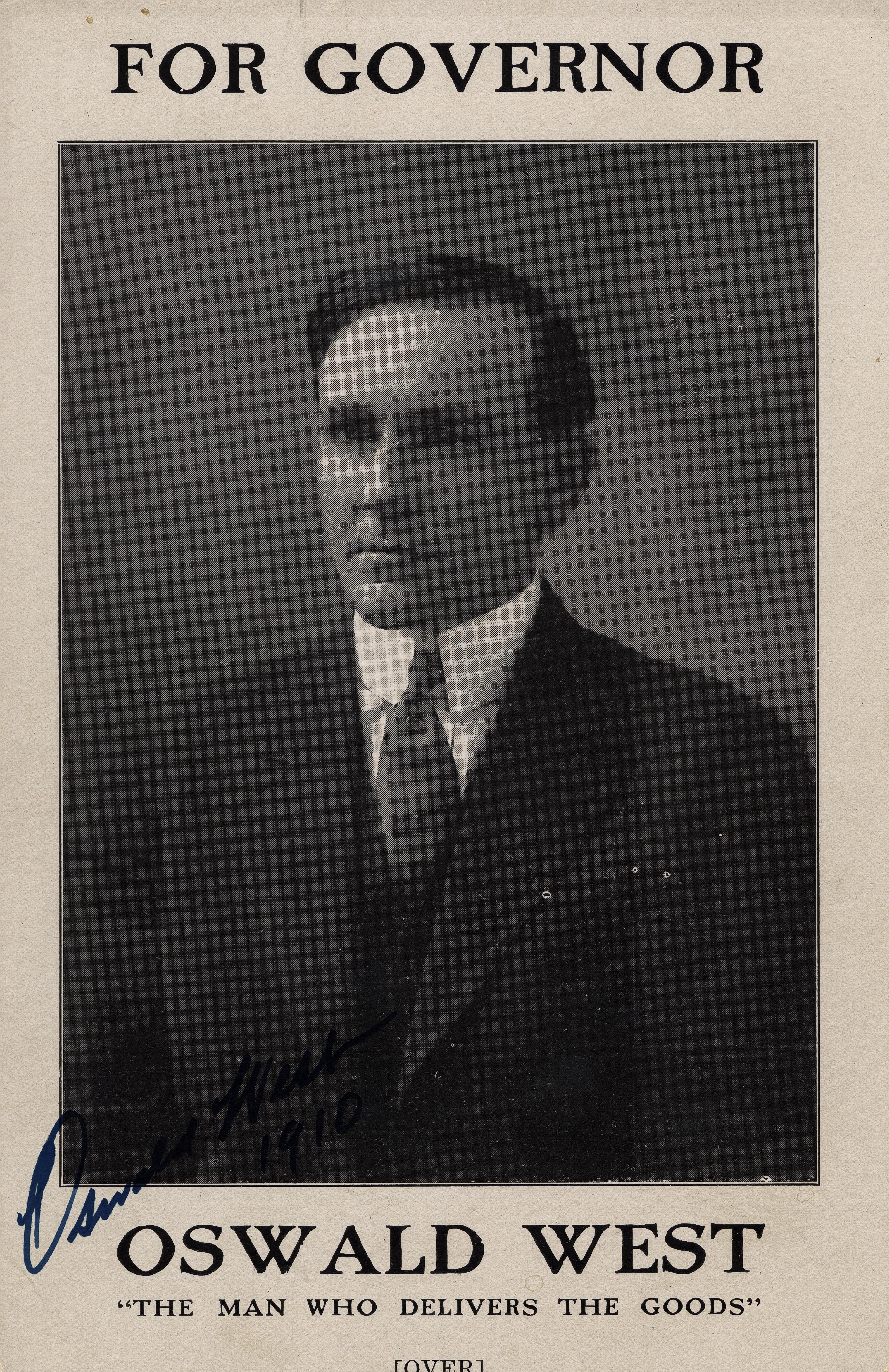

![Oswald D. West (1873-1960)]()

Oswald D. West (1873-1960)

Oswald D. West served as Oregon's fourteenth governor, between 1911 and…

-

Paulina Lake Guard Station

The Civilian Conservation Corps built Paulina Lake Guard Station in 193…

-

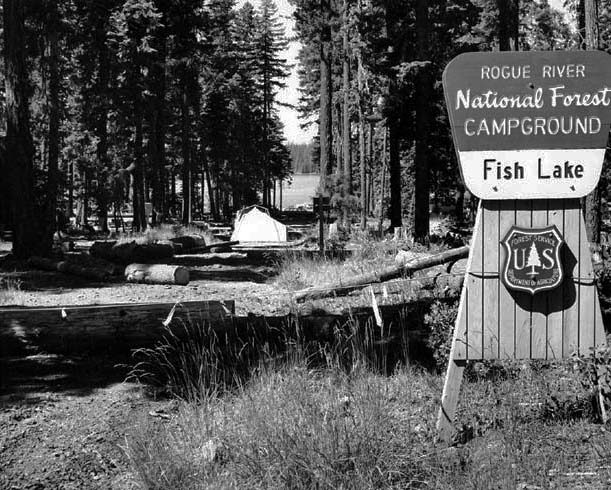

![Rogue River National Forest]()

Rogue River National Forest

For over a century, the Rogue River National Forest has filled an impor…

-

![Siskiyou National Forest]()

Siskiyou National Forest

The Siskiyou Forest Reserve was created on March 2, 1907; within two da…

-

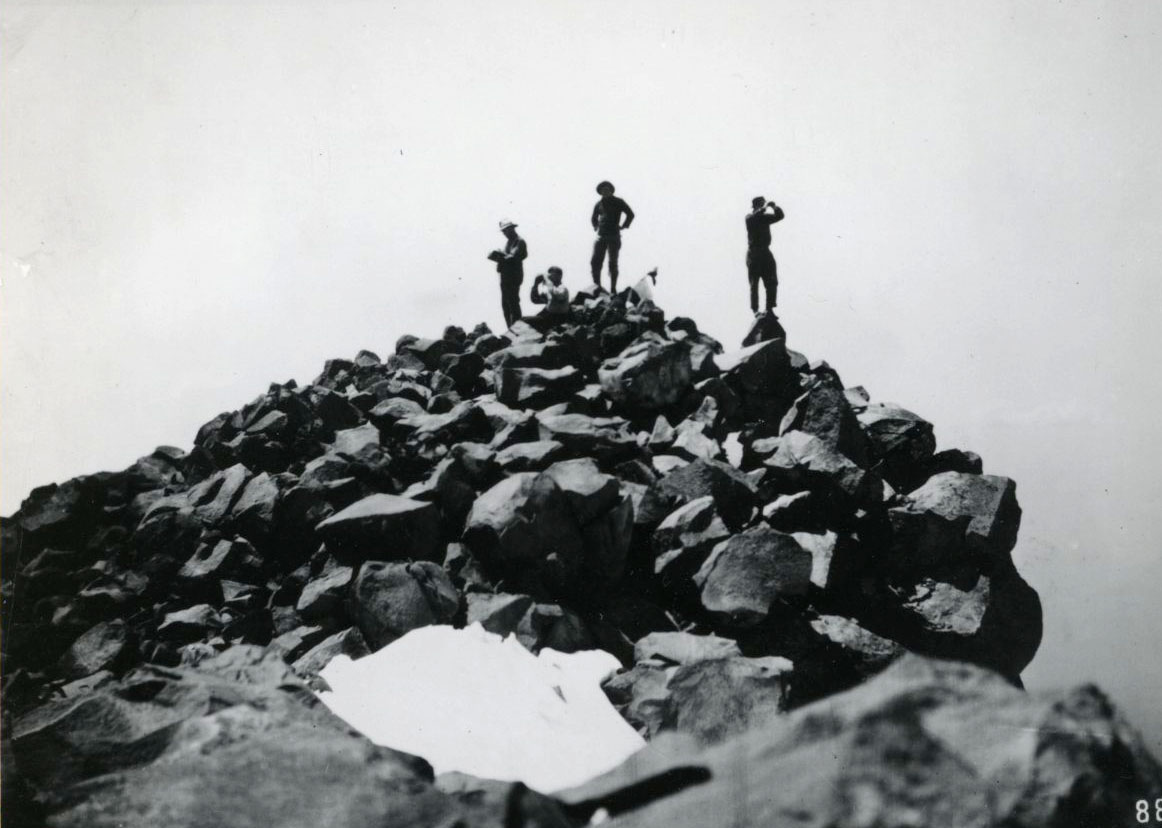

![Strawberry Mountains]()

Strawberry Mountains

The Strawberry Mountains—among the highest peaks in the Blue Mountain R…

-

Thornton Munger (1883-1975)

Thornton Taft Munger was the first director of the U.S. Forest Service'…

-

Three Sisters Wilderness

The Three Sisters Wilderness area in the central Cascade Mountains has …

-

Walter Perry (1873-1959)

Walter Julian Perry arrived in Bend, Oregon, on New Year's Day 1925. He…

-

![William Bernard Milbury (1872-1916)]()

William Bernard Milbury (1872-1916)

William Bernard Milbury was the first federal forest ranger in western …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Rakestraw, Lawrence. A History of Forest Conservation in the Pacific Northwest 1891-1913. New York: Arno Press, 1973.

Williams, Gerald W. The U.S. Forest Service in the Pacific Northwest: A History. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2009.

Williams, Gerald W. and Stephen R. Mark. Establishing and Defending the Cascade Range Forest Reserve from 1885 to 1912. Portland: U.S. Forest Service and Crater Lake, U.S. National Park Service, 1995.