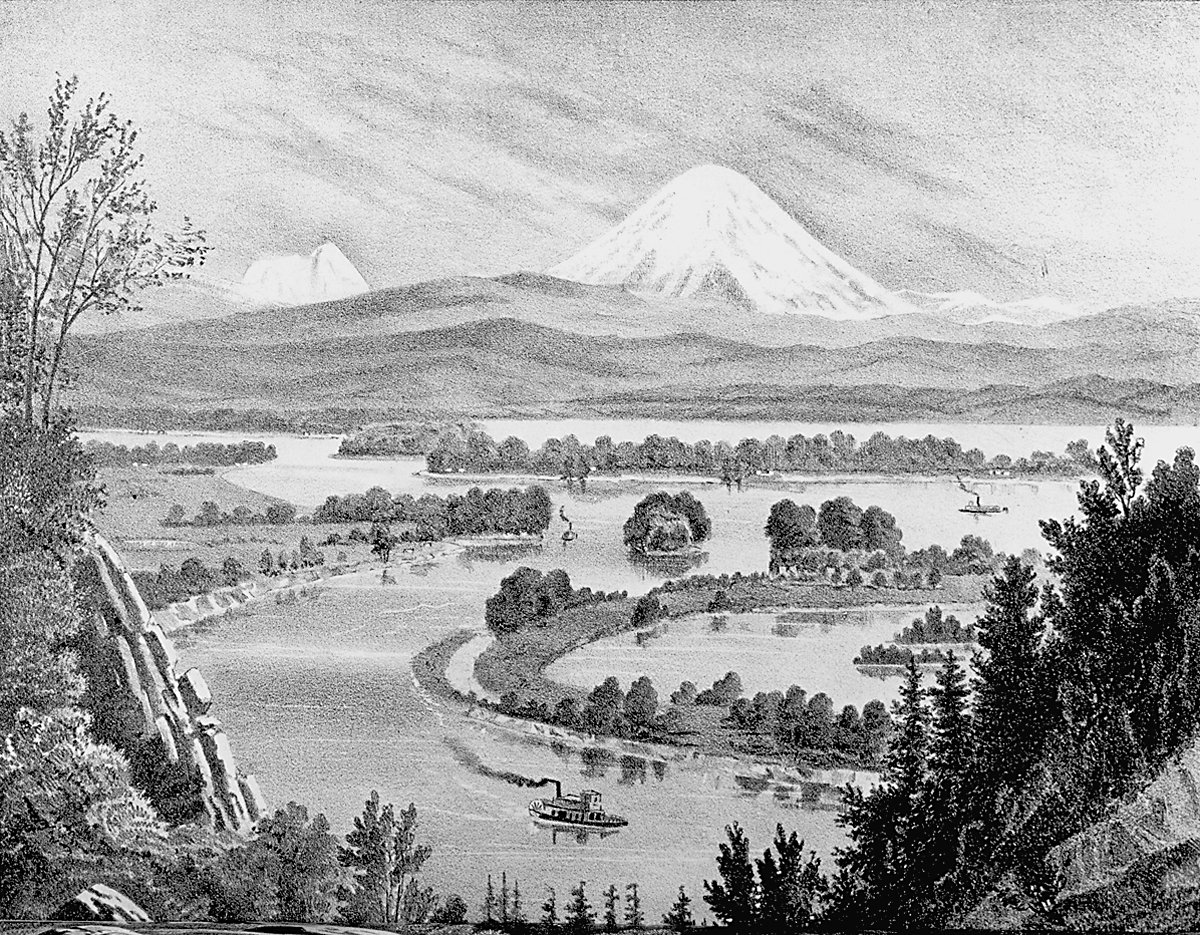

The Willamette National Forest stretches along the western slope of Oregon’s Cascade Range, from Mount Jefferson south to Windigo Pass near Diamond Lake. It borders the Mount Hood National Forest to the north and the Umpqua National Forest to the south. An administrative unit of Region 6 of the U.S. Forest Service, with headquarters in Eugene, the Willamette National Forest is 1.7 million acres, with 123,330 acres managed by private inholders and other public agencies. The Willamette’s mountains and steep valleys range from about 1,500 feet to over 10,000 feet at the summits of the Three Sisters and Mount Jefferson.

The forest’s principal streams include the Willamette, the McKenzie, and the Santiam Rivers and their significant tributaries. Seven large reservoirs on tributary streams control flooding, generate electrical power, and provide recreational benefits. Since World War II, Congress has set aside 380,000 acres in the Willamette National Forest for wilderness, 16,000 acres for the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, and specific areas for recreation and research. Two major river segments are listed as National Wild and Scenic Rivers—thirteen miles of the upper McKenzie River and forty-three miles of the North Fork of the Willamette River.

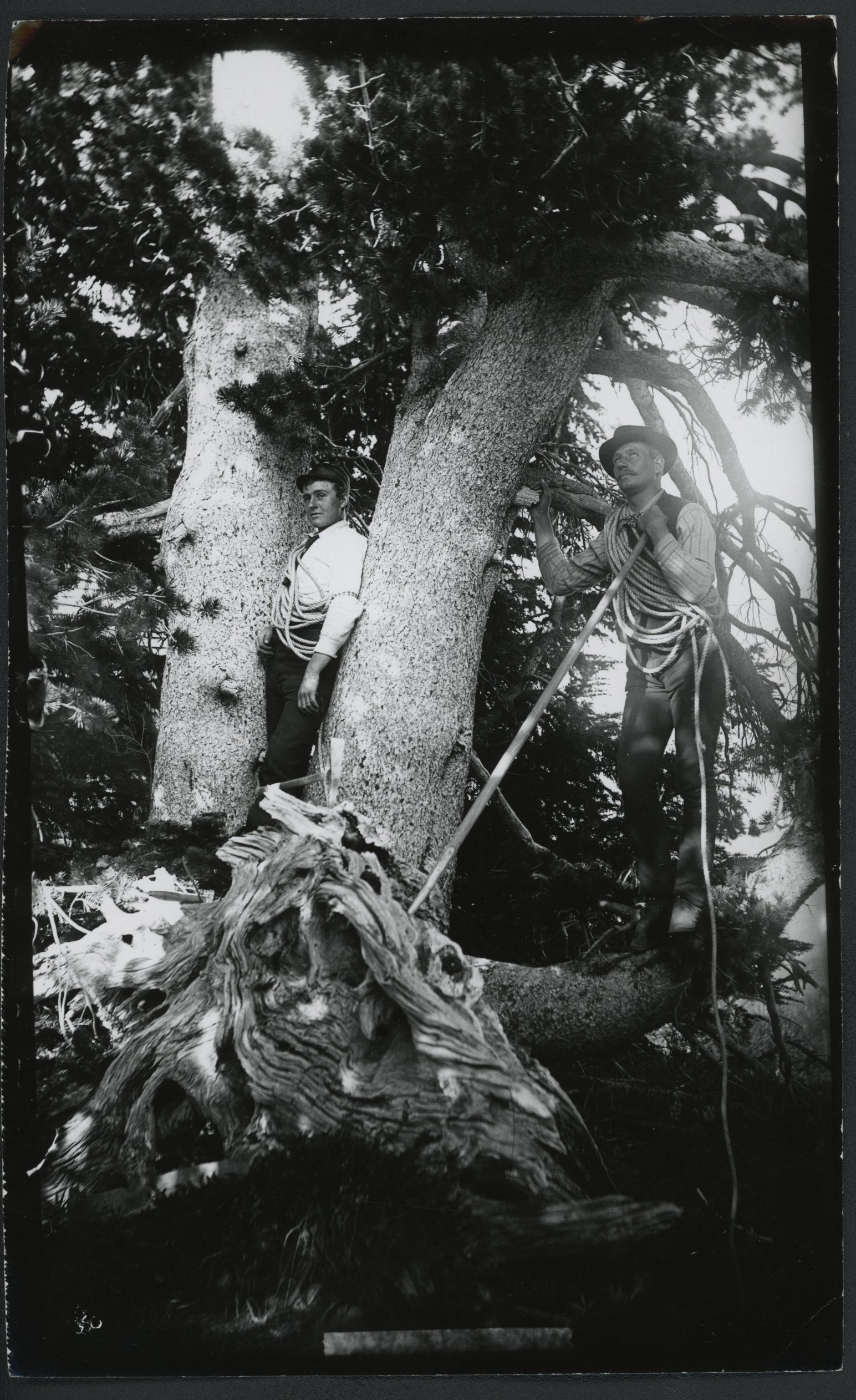

Most of the aboriginal forest in the Willamette National Forest hosted great stands of Douglas-fir, many of the trees measuring three to eight feet in diameter breast high. Western red cedar and hemlock mix with Douglas-fir at lower elevations, giving way to sugar pine, silver, and other species of fir at higher elevations. Studies of tree rings in the historic forest reveal variations in precipitation, the effects of fire and disease, and the ravages of severe windstorms, including the great Columbus Day storm of 1962. The Willamette National Forest is similar to other national forests in Oregon, from the crest of the Cascades to the Pacific, that show the effects of tremendous timber harvests since World War II.

The Land Revision Act of 1891, also known as the Forest Reserve Act, authorized the president to withdraw federal forestlands from public entry. President Grover Cleveland withdrew the Cascade Range Forest Reserve in 1893, 4,883,588 acres extending from the Columbia River along the western slope of the Cascade Range to Crater Lake. The Cascade Reserve, under the jurisdiction of the General Land Office in the Department of the Interior, was transferred in 1905 to the Department of Agriculture, where the Bureau of Forestry (later renamed the Forest Service) assumed control under Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot.

President Theodore Roosevelt used his executive powers in 1907 to create sixteen million acres of federal forests before Congress rescinded the president’s unilateral authority in the Agricultural Appropriations bill of that year. When Roosevelt and Pinchot gave the reserves new names in 1907, the Cascade Reserve became the Cascade National Forest and was divided into the Oregon, Cascadia, and Umpqua National Forests. The Santiam and Cascade National Forests were created from the old Cascadia National Forest in 1911. The Forest Service subsequently combined the Santiam and Cascade Forests to form the Willamette National Forest in 1933.

Because the withdrawals of land were not subject to local taxes and hurt the ability to support schools and roads, state and county officials protested the creation of the reserves and, after 1907, the national forests. Congress eventually required the Forest Service to make payments to states from national forest revenues. Because the receipts were limited to grazing fees and timber harvests, they provided little revenue until the 1920s, and even then such support was minimal because of low timber sales. Throughout those years, staff on the Santiam and Cascade forests continued to extend trail systems and lay telephone lines to seasonal ranger posts.

Early loggers in the Cascades used animal power and river drives to transport logs to sawmills. During the 1920s, larger operators began using railroads in the North Santiam Canyon to deliver logs to mills. Although the Forest Service made some sales, most of the early Cascade timber harvests were on lower-elevation private lands. Significant cutting on the Willamette National Forest did not occur until the 1940s and the national building boom that followed World War II.

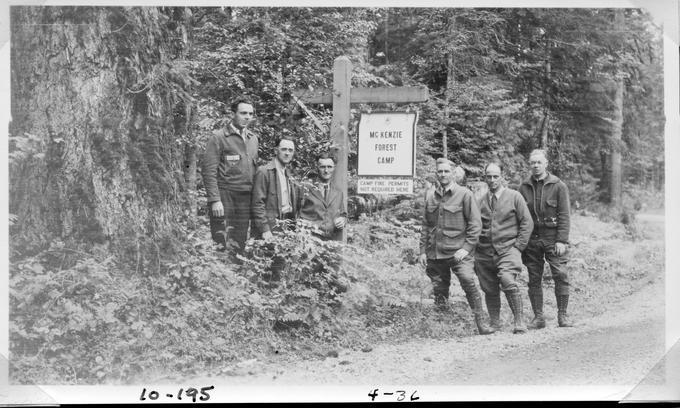

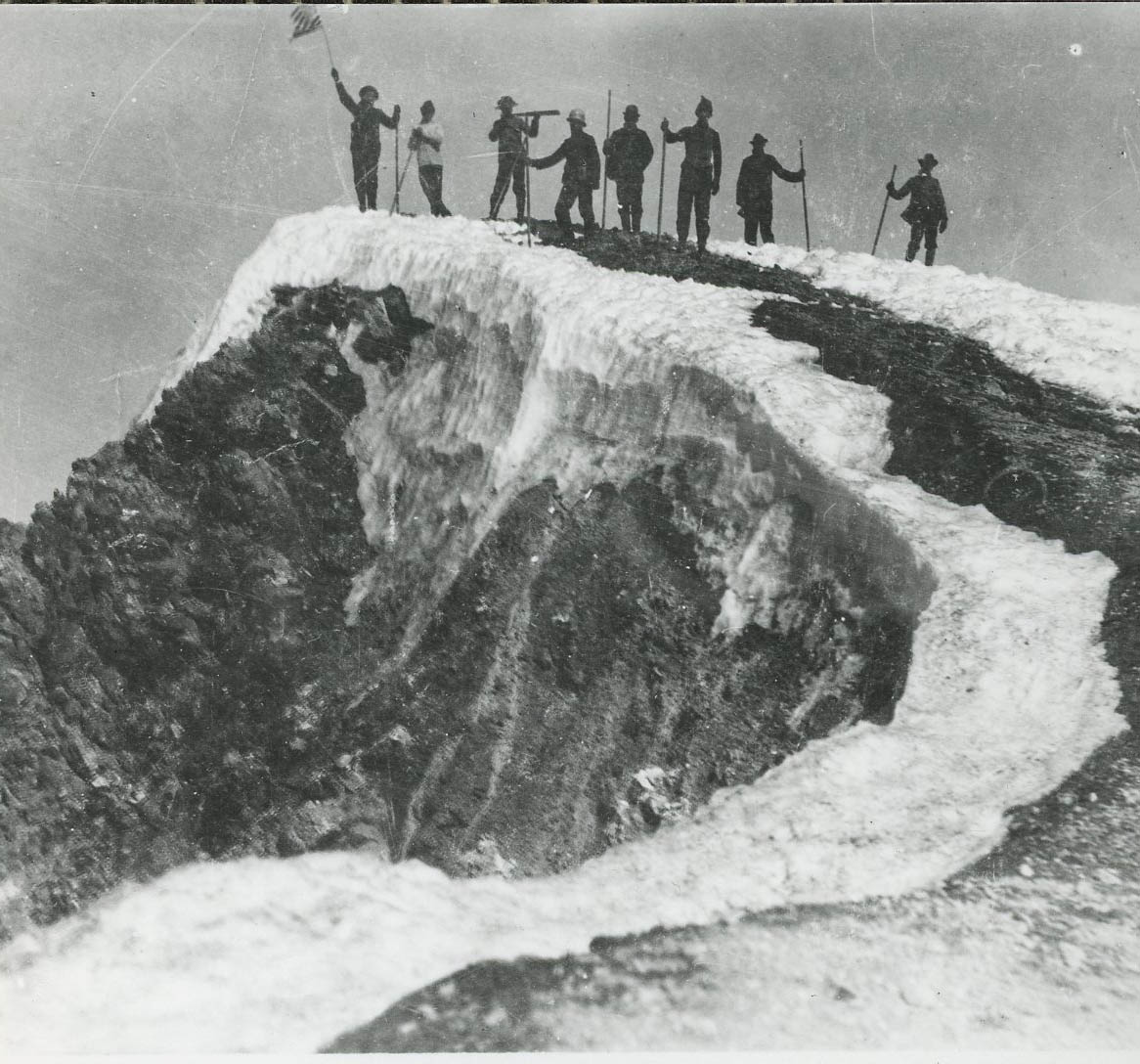

The Willamette National Forest was established during the Great Depression, just as President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal was creating agencies to put people to work. It was a serendipitous moment when Willamette National Forest Supervisor Pat Thompson hired William Parke, the forest’s first recreation officer, at about the same time that the president signed legislation establishing the Civilian Conservation Corps. Between 1933 and 1942, when the program was disbanded, CCC crews constructed trails, lookouts, campgrounds, and other amenities in the Willamette under Parke’s direction. When the Forest Service issued a special permit to develop a ski slope at Hoodoo Butte near Santiam Pass on Highway 20, the CCC built Santiam Lodge, a garage, and a pump house. The Corps’ most significant structure in the Willamette National Forest was the Dee Wright Observatory at McKenzie Pass, on today’s Highway 242. The turret-shaped observatory, another William Parke idea, has thick lava-rock walls, with small ports on the second level framing the Cascades’ spectacular mountain peaks.

During World War II, timber harvests on the Willamette National Forest grew from 44 million board feet in 1940 to 144 million in 1944, an increase that presaged the tremendous harvests of the next four decades. To advance production after the war, timber operators had an array of mechanized equipment, including the chainsaw. To meet production needs, the Forest Service adopted the “conversion” model of forestry—that is, harvesting old-growth, so-called decadent forests and replanting clear-cut areas with vigorous, fast-growing trees.

The 1950s were boom years for “getting out the cut,” and Oregon’s public and private harvests reached an all-time high of 9.1 billion board feet in 1955. Environmental organizations, urging the establishment of wilderness areas, eventually challenged the heavy harvests and Forest Service management prerogatives. With the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964, three wilderness areas were established in the Willamette National Forest, including the Three Sisters Wilderness. Congress created five additional wilderness areas in the Willamette between 1968 and 1996. The most controversial was the French Pete drainage, which the Forest Service had targeted for harvesting until a groundswell of opposition, much of it from the Eugene area, persuaded Oregon Senator Bob Packwood to push a measure through Congress. The French Pete drainage was added to the Three Sisters Wilderness in 1978.

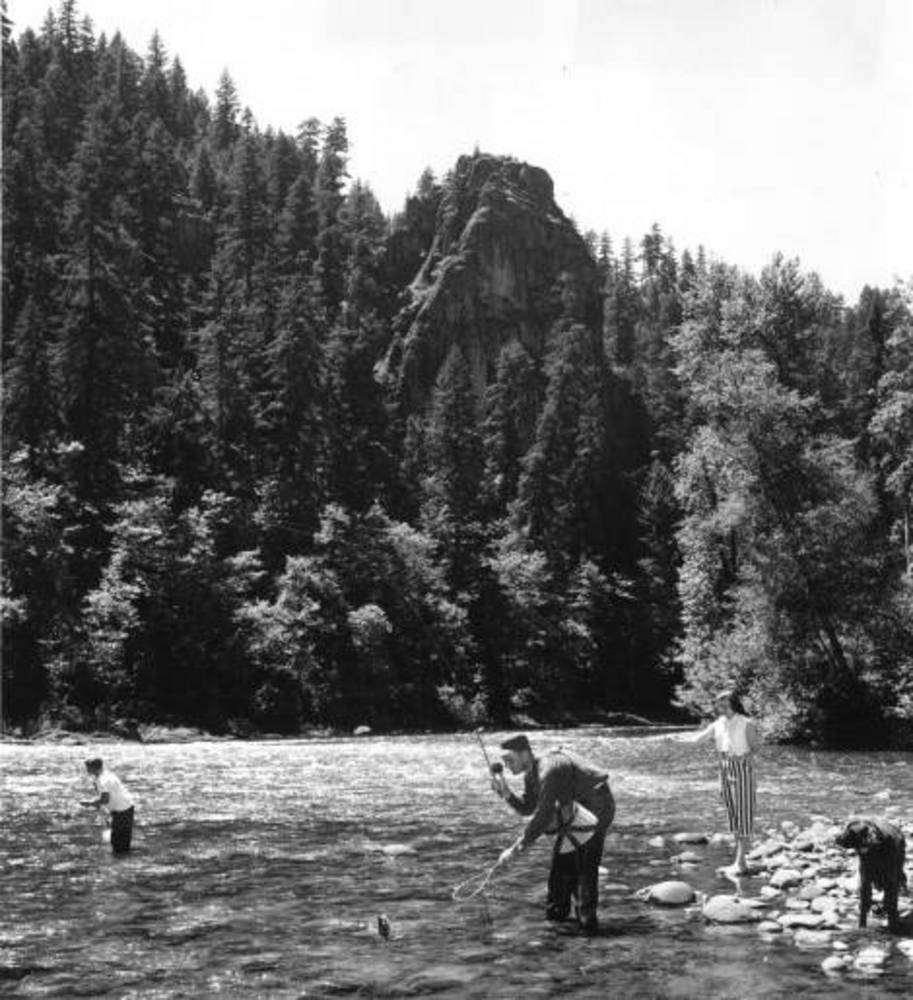

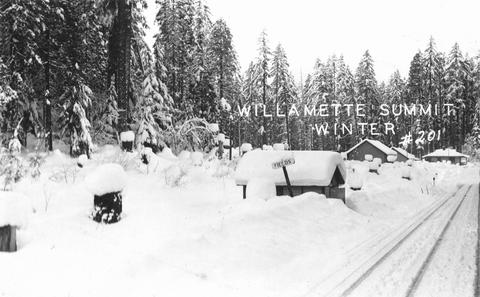

Americans increasingly camped, fished, and hiked in the Willamette National Forest after World War II. Improved travel from population centers in the Willamette Valley and an expanding system of forest roads provided access to the backcountry. The Forest Service extended its trail system, built new campgrounds, and modernized others. The Sierra Club and other environmental organizations advocated for more wilderness areas in Oregon and contributed to greater numbers of people spending time in the Cascade Range, hiking the Three Sisters Wilderness, fishing the high lakes, and visiting the expansive lava fields near the Dee Wright Observatory. Winter sporting includes skiing at the Hoodoo, Mount Bachelor, and Willamette Pass ski areas, riding snowmobiles outside wilderness areas, and skiing cross-country trails in the high country.

Significant natural events periodically struck western Oregon and the Willamette National Forest. The Columbus Day storm in 1962 blew down a huge volume of timber, causing logjams on major streams and creating an uptick in salvage timber sales. Two years later, the Christmas-week floods of 1964 damaged highways, forest roads, and campgrounds. In early 1996, heavy snowfall in the Cascades, followed by rain and warming temperatures, caused major flooding in western Oregon. The best data and eyewitness accounts on the Willamette National Forest were gathered on the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest, where scientists observed the cascading waters of Lookout Creek and its tributaries.

Environmental issues affected management practices on the Willamette and other national forests in the 1970s. The Forest Service’s work to replant clear-cuts and accelerate the growth of new trees involved the heavy use of herbicides, including 2,4,5-T, a chemical used in Agent Orange. When the Defense Department ended the use of the herbicides in Vietnam because of reports of miscarriages and deformed babies, activists in rural Oregon protested the use of 2,4,5-T in the national forests, especially in the Siuslaw along Oregon’s Coast Range. The Environmental Protection Agency eventually delisted use of the herbicide on all national forests.

The large postwar timber harvests on the Willamette and other national forests in the Northwest came to a halt in May 1991 when District Judge William Dwyer issued an injunction blocking federal timber sales until the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management met the requirements of the National Forest Management Act (1976). The judge’s decision cited harm to the spotted owl, an endangered species, whose habitat was old-growth forests. Dwyer chastised the Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service for their deliberate refusal to follow the law. The unsustainable timber harvests from the 1960s through the 1980s—encouraged by mill owners who were running out of private timber—contributed to the crisis. From that point forward, declining timber revenues made it difficult for the Willamette National Forest to meet its multiple-use responsibilities, including recreation.

President Bill Clinton’s Northwest Forest Plan in 1994 resumed limited timber harvests—primarily thinning operations of small trees—but at a fraction of the Forest Service cut allowed over the previous two decades. In addition, appropriations devoted to firefighting consumed an increasing percentage of the agency’s budget in the twenty-first century. Because Congress has refused to fund firefighting as a separate line item, the Forest Service has been forced to reduce staffing, close campgrounds, and require fees for entering wilderness and special-use areas. Volunteers now maintain the trail systems in the Willamette National Forest, including the iconic Pacific Crest Trail, and the reductions in timber harvesting on the Willamette and other national forests continue to be a hot-button issue.

-

![]()

-

![]()

Oakridge planting station, Willamette National Forest, 1924.

Courtesy Gerald W. Williams Collection, Oregon State University. "Oakridge planting station" Oregon Digital -

![]()

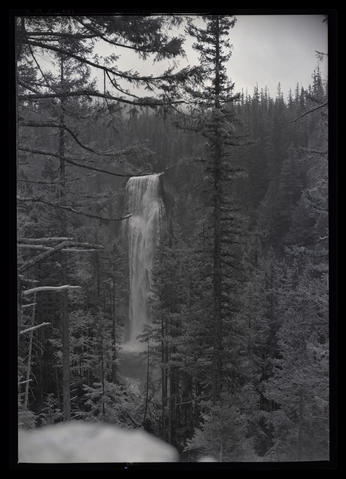

Salt Creek Falls, Willamette Highway, Gilliam Portrait Studio and Camera Shop negatives, 1930-1970.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Digital Collections, Org. Lot 1275; Box 2; S-233

-

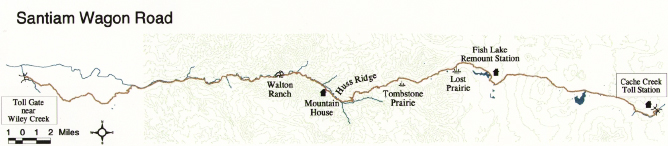

Santiam Wagon Road map, USFS.

Map of Santiam Wagon Road. U.S. Forest Service

Related Entries

-

![Cascade Mountain Range in Oregon]()

Cascade Mountain Range in Oregon

The Cascade mountain system extends from northern California to central…

-

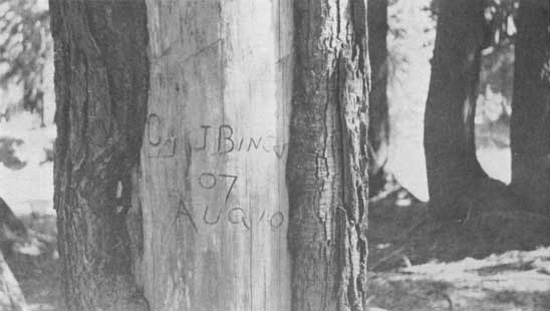

![Cyrus Bingham (1870-1937)]()

Cyrus Bingham (1870-1937)

Cyrus James “Cy” Bingham, an early U.S. forest ranger, serv…

-

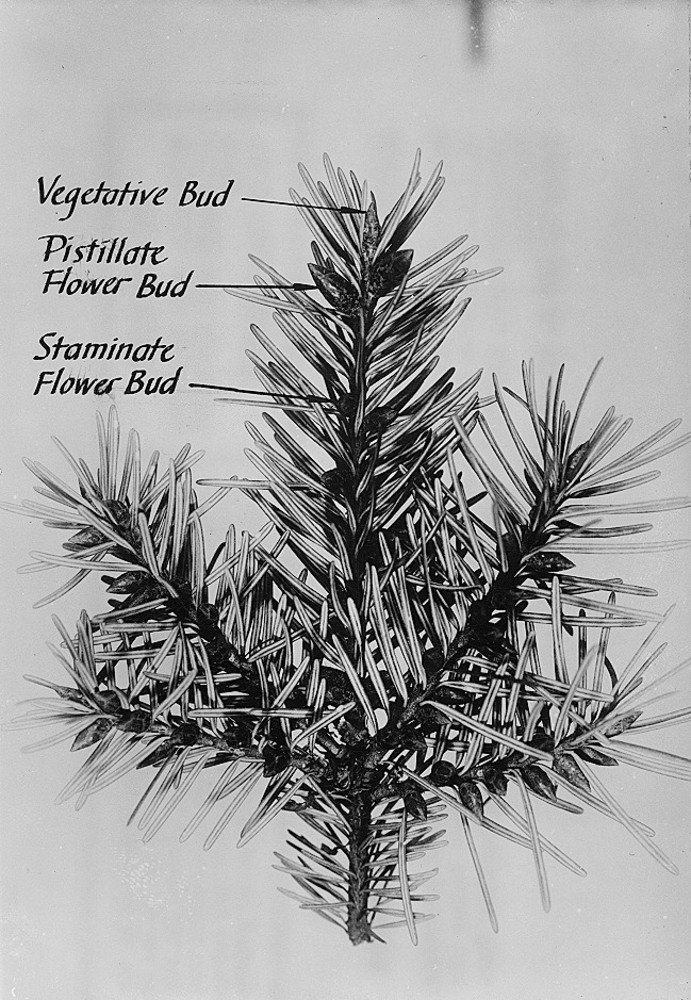

![Douglas-fir]()

Douglas-fir

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), perhaps the most common tree in Or…

-

![Hart Mountain Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Camp]()

Hart Mountain Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) Camp

Camp Hart Mountain, a Civilian Conservation Corps camp, operated from O…

-

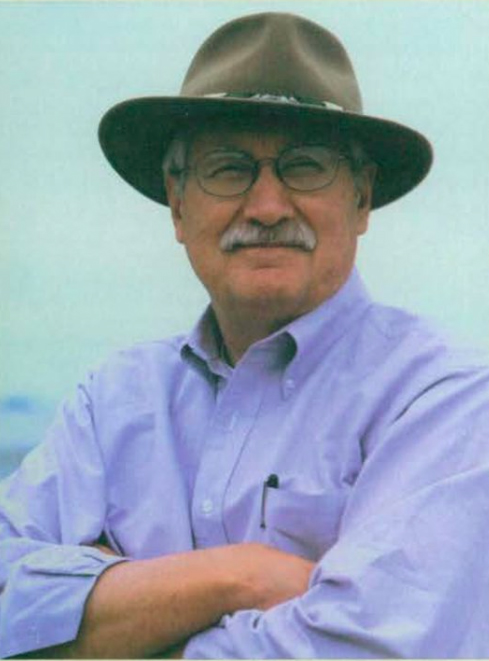

![Jerry F. Franklin (1936-)]()

Jerry F. Franklin (1936-)

Jerry F. Franklin’s early experiences in Oregon and Washington forests …

-

![McKenzie River]()

McKenzie River

The McKenzie River, on the western slope of the Cascade Range, starts o…

-

![National Forests in Oregon, 1892 to 1933]()

National Forests in Oregon, 1892 to 1933

The first forest reserves in the state were established in 1892-1893, a…

-

![Santiam Pass]()

Santiam Pass

Santiam Pass, at an elevation of 4,817 feet, is a major highway crossin…

-

Santiam Wagon Road

The Santiam Wagon Road was a vital commercial link connecting the Willa…

-

![Siskiyou National Forest]()

Siskiyou National Forest

The Siskiyou Forest Reserve was created on March 2, 1907; within two da…

-

Three Sisters Wilderness

The Three Sisters Wilderness area in the central Cascade Mountains has …

-

![Western hemlock]()

Western hemlock

Western hemlock, or Alaska-spruce (Tsuga heterophylla), is a common con…

-

![Western red cedar]()

Western red cedar

Western red cedar (Thuja plicata) is one of the grand trees that grows …

-

![Willamette Pass]()

Willamette Pass

Willamette Pass, a 5,128-foot-high mountain pass in the Cascade Range, …

-

Willamette River

The Willamette River and its extensive drainage basin lie in the greate…

-

![William A. Langille (1868-1956)]()

William A. Langille (1868-1956)

While some have called William A. Langille the father of forestry in Al…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

"A Brief History of the Willamette National Forest." USDA, Forest Service, Willamette National Forest.

Rakestraw, Lawrence. History of the Willamette National Forest. Eugene, Ore.: USDA-Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Region, 1991.

Robbins, William G. Landscapes of Promise: The Oregon Story, 1800-1940. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Robbins, William G. Landscapes of Conflict: The Oregon Story, 1940-2000. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000.