Tobacco is native to the Americas, including in the Pacific Northwest, where it was harvested and often cultivated for thousands of years. Introduced to Europe by Christopher Columbus, who first saw the plant on an island in the Bahamas in October 1492, tobacco subsequently was spread throughout the world by early maritime traders and explorers.

There are many species of the tobacco plant, but two principal native species grow in western North America. Nicotiana attenuata, the so-called coyote tobacco, is common throughout the drier climate of the Desert West, while Nicotiana quadrivalvis, sometimes called Indian tobacco, has a more coastal range, extending from southern California to Oregon. Other plants are sometimes mixed with tobacco, including manzanita (Arctostaphylos columbiana); kinnikinnick, also known as bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi); sumac (Rhus glabra), and willow bark.

Tobacco (Nicotiana attenuata) seeds have been recovered from hearths, coprolites, and food-cooking pits in present-day Oregon, Idaho, and Utah. The earliest seeds were found in a cultural hearth in Utah dating to about 12,300 years ago. It is not clear whether tobacco was smoked, chewed, or consumed in teas in these contexts—that is, the environment within which the object was found and connected to—but the presence of charred seeds in cultural features confirms the great antiquity for human tobacco use in the American West.

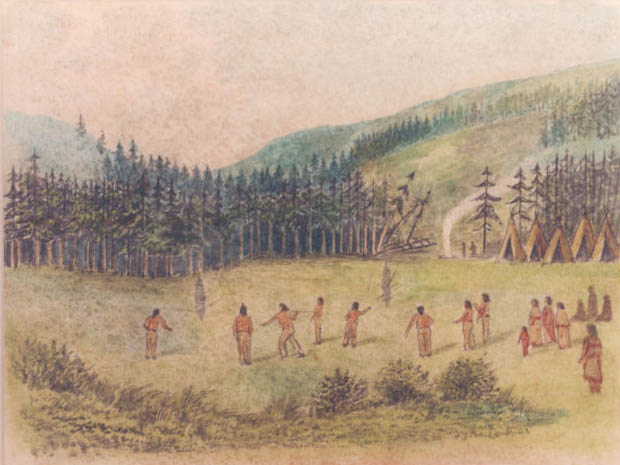

Tobacco was cultivated by many Native groups in western North America who actively managed plants by burning, pruning, and harvesting them selectively to enhance productivity. It was often the only plant for which some groups purposefully prepared the soil and planted seed, including by people who lived beyond tobacco’s natural range. There is evidence to suggest that Nicotiana quadrivalvis gardens were maintained among the Haida, Tsimshian, and Tlingit of British Columbia and southeast Alaska, indicating that tobacco had been spread through trade and intentionally cultivated before encounters with non-Natives. Scottish botanist David Douglas reported finding a tobacco garden near a village on the Multnomah River (the present-day Willamette River) in 1825: "An open place in the wood is chosen where there is dead wood, which they burn, and sow the seed in the ashes….I met the owner who…told me that wood ashes made it grow very large."

Two decades earlier, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had found that tobacco was being grown by groups they encountered during their trek to the Pacific. Clark wrote on October 12, 1804, that Arikaras in the Dakotas “raise great quantites [sic] of corn beans &c also Tobacco for the men to Smoke.” In December 1805, while wintering at Fort Clatsop, Clark purchased “a Small pouch of Tobacco of their own manufactory” from some Chinook people, and Lewis observed on January 8, 1806, that "the Clatsops Chinnooks and others inhabiting the coast and country in this neighbourhood, are excessively fond of smoking tobacco." Smoking was an element in important decision-making occasions, Clark wrote, and tobacco was "indispenceable [sic] in those cases." Throughout their journey, members of the expedition traded tobacco for food and other essentials.

Tobacco has long been considered a sacred plant throughout Native America, used in prayer and to solemnize formal occasions but used in other social contexts as well. In 1932, ethnographer J. P. Harrington, who worked among tribes of coastal Oregon and California, described some of the ways Karuk, on the lower Klamath River, used tobacco. When men met on a trail, for example, one would treat the other to his tobacco and the second would reciprocate. A hunter spread tobacco on the ground to "feed the mountain" and to offer thanks for the game he hoped to take. Tobacco was used in public ritual, in personal prayer for luck in gambling or hunting, and as medicine for ailments. It was consumed recreationally and was sometimes smoked to achieve altered consciousness, a result of the psychoactive properties of nicotine.

Nonritual tobacco use varied from group to group. In her 1932 ethnography about the Paiute people, Isabel Kelly (1932) reported that “smoking was solely a male indulgence,” while ethnographer Leslie Spier (1930) found that among the Klamath “women use tobacco as freely as men.” Spier and Sapir (1930) wrote that smoking was mainly an activity of chiefs and shamans among the Wishram on the Columbia River.

Aboriginal smoking pipes are most commonly tube pipes (or cloud blowers) that have an unangled hole from bowl to mouthpiece, and elbow pipes whose bowls are angled from the mouthpiece. Pipes were most commonly made from stone, such as steatite/soapstone, catlinite/pipestone, siltstone/sandstone, and volcanic tuff; they were also made of clay and sometimes wood. Often a stem mouthpiece—a tube of cane or hollow bone—was added.

Among the oldest pipes and pipe fragments known in western North America are from sites in Washington, Oregon, and California. Four pipes from a site near present-day East Wenatchee, Washington, have been reported from a context dating to about 4,500 years ago. Three sites in the Fort Rock and Silver Lake basins in Oregon have pipes dating from about 5,600 and 3,600 years ago. Pipes from a site in California’s Tulelake subbasin, which is in the Klamath Basin, are from contexts dating more than 5,000 years old. Pipes have also been found in much more recent sites. Researchers analyze smoking residues on ancient pipes to identify nicotine and other smoking products to confirm their use for tobacco.

Native communities continue to regard tobacco as a sacred element. Commercial tobacco is widely used, but some tribes are now cultivating the local varieties used by their ancestors. Practices differ among tribes, who might sprinkle tobacco as part of ritual or burn it in a dish so the smoke can carry prayers to the Creator. In modern times, the tobacco might be smoked but not inhaled. In contrast to the modern association of tobacco with death and illness, tobacco is a symbol for peace and healing among many American Native communities, where its traditional association with peaceful negotiation, with medicine, and with prayer remains strong.

-

![]()

Chief Tamason or Timothy (Nez Perce) holding an elbow pipe, 1868.

Courtesy Smithsonian National Museum of American History -

![]()

Nicotiana quadrivalvis Pursh.

Courtesy Oregon Flora -

![Lee Moorhouse heavily curated his images of Native people.]()

Chief Five Crows (Cayuse) holding a pipe in his left hand, c. 1900.

Lee Moorhouse heavily curated his images of Native people. Picturing the Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Umatilla Tribes, University of Oregon. "Chief Five Crows Cayuse Tribe" Oregon Digital. -

![]()

Coyote Tobacco (Nicotiana attenuata).

Courtesy Oregon Flora -

![]()

Sumac (Rhus glabra).

Courtesy Oregon Flora -

![]()

Kinnikinnik (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi).

Courtesy Oregon State University

Related Entries

-

![Camas]()

Camas

Camas is a North American bulb-forming geophyte whose greatest diversit…

-

![Indian Use of Fire in Early Oregon]()

Indian Use of Fire in Early Oregon

Anthropogenic (human-caused) fire was a major component of the Native s…

-

![Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the early 1800s]()

Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the early 1800s

During the early nineteenth century, upwards of thirty Native American …

-

![Tules]()

Tules

In Oregon and much of the western United States, tule is the common nam…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Arkush, Brooke S., and Denise Arkush. "Aboriginal Plant Use in the Central Rocky Mountains: Macrobotanical Records from Three Prehistoric Sites in Birch Creek Valley, Eastern Idaho." North American Archaeologist 42.1 (66-108): 2021.

"History of Native American Pipes." Luther College, Decorah, Iowa.

Bollwerk, Elizabeth A., and Shannon Tushingham, eds. Perspectives on the Archaeology of Pipes, Tobacco and other Smoke Plants in the Ancient Americas. New York: Springer International, 2016.

Bull, Brian. "Once thought lost for good, Native Americans' prized tobacco is back in Oregon." Oregon Public Broadcasting. November 21, 2023.

Connolly, Thomas J., Christopher L. Ruiz, Dennis L. Jenkins, and Douglas Deur. "This Place is Home: Exploring Heritage and Community of the Klamath Tribes at the Beatty Curve Site (35KL95)." University of Oregon Museum of Natural and Cultural History Museum, Report 2015-006, Eugene, 2015.

Coville, Frederick V. "Notes on the Plants Used by the Klamath Indians of Oregon." Contributions to the U.S. National Herbarium 5.2 (1897): 87-107.

Damitio, William J., Shannon Tushingham, Korey J. Brownstein, R. G. Matson, and David R. Gang. "The Evolution of Smoking and Intoxicant Plant Use in Ancient Northwestern North America." American Antiquity 86.4 (2021): 715-733.

Duke, Daron, et al. "Earliest Evidence for Human Use of Tobacco in the Pleistocene Americas." Nature Human Behaviour 6 (2022): 183-192.

Galm, Jerry R., and Dana Komen. "Cox’s Pond and Middle Holocene Ceremonial Activity in the Inland Pacific Northwest." In Festschrift in Honor of Max G. Pavesic, edited by Kenneth C. Reid and Jerry R. Galm. Journal of Northwest Anthropology Memoir 7 (2012): 73-96.

Harrington, John P. "Tobacco among the Karuk Indians of California." Smithsonian Instituion Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 94 (1932).

Jenkins, Dennis L. "Archaeological Investigations at Three Wetlands Sites in the Silver Lake Area of the Fort Rock Basin." In Archaeological Researches in the Northern Great Basin: Fort Rock Archaeology Since Cressman, edited by C. Melvin Aikens and Dennis L. Jenkins, 213-258. Eugene: University of Oregon Anthropological Papers, Museum of Natural & Cultural History, 1994.

Kennedy, Jaime L., and Geoffrey M. Smith. "Paleoethnobotany at the LSP-1 Rockshelter, South Central Oregon: Assessing the Nutritional Diversity of Plant Foods in Holocene Diet." Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 5 (2016): 640-648.

Jenkins, Dennis L., Thomas J. Connolly, and C. Melvin Aikens, eds. "Early and Middle Holocene Archaeology of the Northern Great Basin." University of Oregon Anthropological Papers 62 (2004): 95-122.

Moss, Madonna. "Tlingit Horticulture: An Indigenous or Introduced Development?" In Keeping It Living: Traditions of Plant Use and Cultivation on the Northwest Coast of North America, edited by Douglas Deur and Nancy Turner, 274-295. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2005.

Struthers, Roxanne, and Felicia S. Hodge. "Sacred Tobacco Use in Ojibwe Communities." Journal of Holistic Nursing 22.3 (2004): 209-222.

Turner, Nancy. Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America. Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2014.

Tushingham, Shannon, et al. "Hunter-gatherer tobacco smoking: earliest evidence from the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America." Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (2013): 1397-1407.

Tushingham, Shannon, et al. "Biomolecular archaeology reveals ancient origins of indigenous tobacco smoking in North American Plateau." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115.46 (2018): 11742–11747.

Whereat Phillips, Patricia. "History and Modern Use of Sacred Tobacco on the Central and Southern Oregon Coast." In Perspectives on the Archaeology of Pipes, Tobacco and other Smoke Plants in the Ancient Americas, edited by Elizabeth A. Bollwerk and Shannon Tushingham, 199-210. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Publishing, 2016.