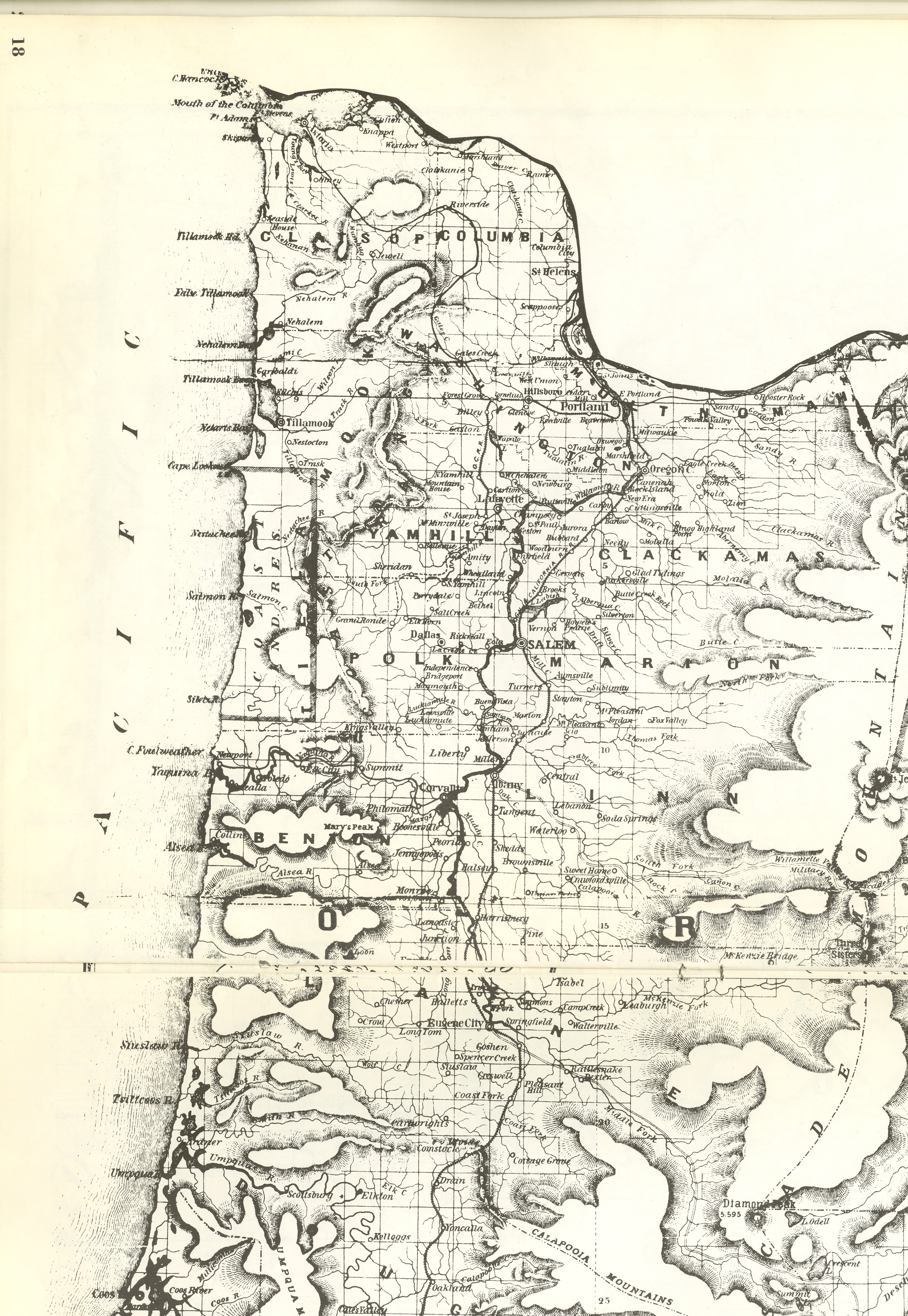

When Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Law in 1850, the legislation set in motion procedures for the disposal of public lands that left a permanent imprint on the Oregon landscape. The grid-square pattern of property ownerships imposed on rural lands in the Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue valleys is visible to the present day.

Arguably the most generous federal land act in American history, the law legitimized the 640-acre claims provided in 1843 under the Oregon Provisional Government, with the proviso that white male citizens were entitled to 320 acres and their wives were eligible for 320 acres. For citizens arriving after 1850, the acreage limitation was halved, so a married couple could receive a total of 320 acres. To gain legal title to property, claimants had to reside and make improvements on the land for four years.

The 1850 law originally set a two-year window for surveying lands open for claims, limiting the offer to December 1, 1853, but Congress amended the law twice. In 1853, the rights of widows to land claims was added, and the law was extended until 1855 to address complaints about the slow progress in surveying lands. In 1854, Congress again amended the law by reducing the residency requirement from four years to one year.

Section 4 of the Donation Law outlined the requirements for eligibility: “granted to every white settler or occupant of the public lands, American half-breed Indians included, above the age of 18 years, being a citizen of the United States, or having made a declaration according to law of his intention to become a citizen.” In effect, the Oregon Donation Land Law benefited incoming whites and dispossessed Indians.

To meet constitutional requirements, Territorial Delegate Samuel Thurston had told Congress that extinguishing Native title to land was the “first prerequisite step” to settling Oregon’s land question. Therefore, before lawmakers voted for the Donation Land Law, they passed legislation authorizing commissioners to negotiate treaties to extinguish Indian title and to remove tribes "and leave the whole of the most desirable portion open to white settlers.”

While the Donation Land Law explicitly excluded Blacks and Hawaiians, the act validated white settler claims in the Willamette Valley and attracted an in-rush of people to the Umpqua and Rogue valleys. In the Willamette Valley, Kalapuya bands had suffered catastrophic losses from seasonal malaria outbreaks during the early 1830s, but bands in the Rogue Valley were still numerous and resisted the incursions of whites, especially miners, in the 1850s. The consequence was something akin to a race war in 1852 and 1853, with white volunteer forces ruthlessly driving Natives from their traditional hunting and gathering grounds. Regular U.S. Army troops eventually removed most of the surviving bands to the newly established Coast Reservation.

The Donation Land Law was significant in shaping the course of Oregon history. By the time the law expired in 1855, approximately 30,000 white immigrants had entered Oregon Territory, with some 7,000 of them making claims to 2.5 million acres of land. The overwhelming majority of the claims were west of the Cascade Mountains. Oregon’s population increased from 11,873 in 1850 to some 60,000 by 1860.

-

![]()

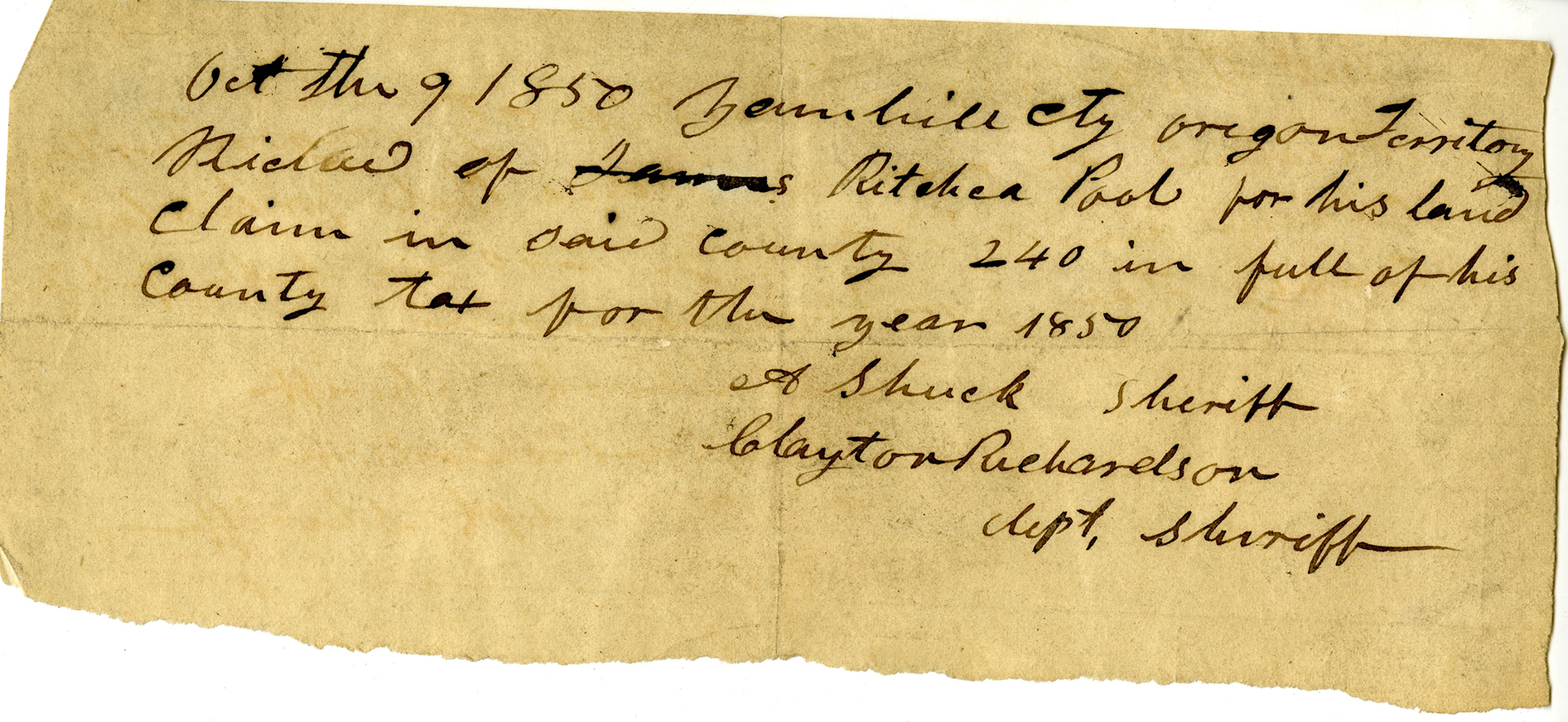

Tax receipt for a donation land claim, October 9, 1850.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss1501, box 1, land tax folder

-

![]()

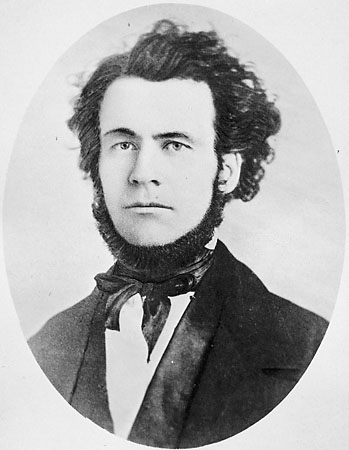

Samuel Thurston.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 020665

-

![]()

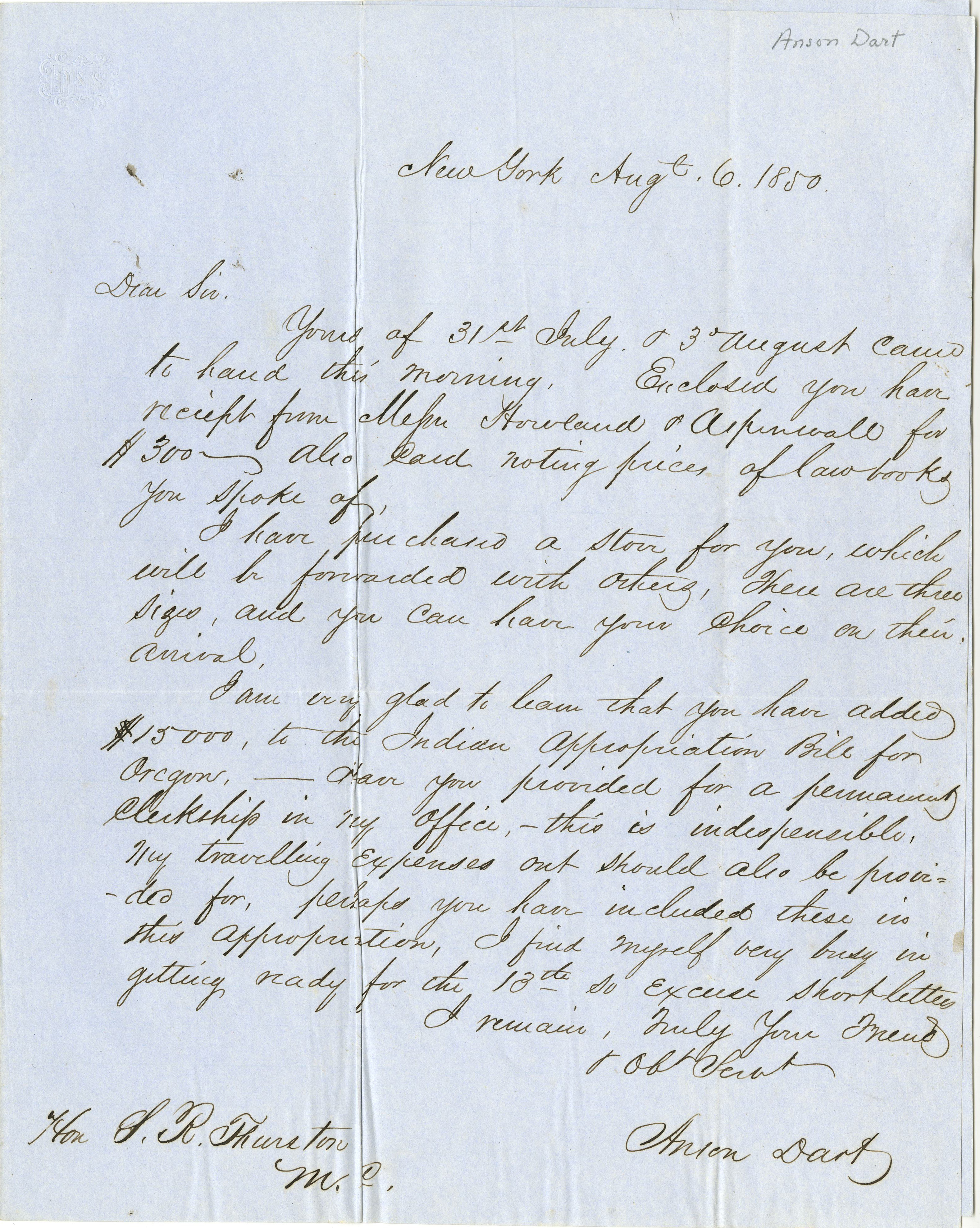

Letter from Anson Dart to Thurston, Aug. 6, 1850.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss379, folder 3

Related Entries

-

![Kalapuyan peoples]()

Kalapuyan peoples

The name Kalapuya (kǎlə poo´ yu), also appearing in the modern geograph…

-

![Oregon Land Survey, 1851-1855]()

Oregon Land Survey, 1851-1855

In 1850, President Millard Fillmore appointed John B. Preston as Oregon…

-

![Provisional Government]()

Provisional Government

The Provisional Government, created in May-July 1843, was the first gov…

-

![U.S. General Land Office in Oregon, ca. 1850-1946]()

U.S. General Land Office in Oregon, ca. 1850-1946

With the acquisition of the Oregon Country in 1846, the United States w…

-

![Willamette Stone and Willamette Meridian]()

Willamette Stone and Willamette Meridian

Land surveys accomplished under the U.S. Government's Rectangular Surve…

-

![Willamette Valley]()

Willamette Valley

The Willamette Valley, bounded on the west by the Coast Range and on th…

Related Historical Records

Further Reading

Johansen, Dorothy O. Empire of the Columbia: A History of the Pacific Northwest. 2d ed. New York: HarperCollins, 1967.

Pomeroy, Earl. The Pacific Slope: A History. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1965.

Robbins, William G. Landscapes of Promise: The Oregon Story, 1800-1940. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997.

Robbins, William G. Oregon, This Storied Land. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2005.