For years after achieving statehood in 1859, Oregon was deprived of a proper capitol due to controversy over fixing the seat of government in Salem. The Classical Revival territorial capitol had burned under suspicious circumstances in 1855; thereafter, legislators assembled in rented rooms in commercial buildings in Salem’s downtown. The Oregon Constitution, enacted in 1857, prohibited expenditure of public funds on a capitol building before 1865, by which time Salem was confirmed as the capital by a vote of the people.

The first state capitol was opened for use in 1876 and finished in stages until, in 1893, it was complete with a central dome. Thomas U. Walter’s iron dome, added to the national capitol in 1859-1863, had provided fresh inspiration to capitol builders across the country. An imposing three-story structure of brick and native Umpqua sandstone, the Oregon state capitol also was Classical in style, but it combined features of Italian Renaissance architecture with those drawn from antiquity.

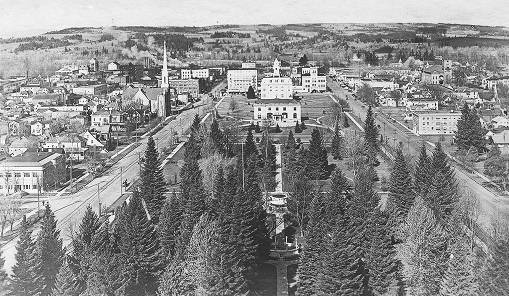

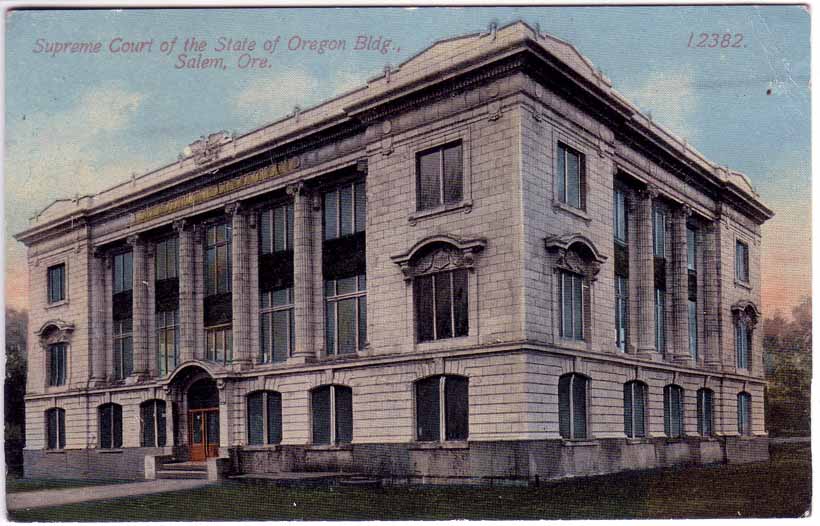

The building occupied block 84 in the town plat filed by former Methodist missionary William H. Willson in 1846. The short-lived territorial capitol had occupied the same site, which had been reserved for a capitol at the head of Willson Avenue, an elongated public square closely bordered by churches and some of the city’s finest residences. Opposite the lower, west end of the square, the Marion County Courthouse of 1873 stood on axis with the monumental state house. The buildings faced west toward the Willamette River and the heart of town. The old capitol housed the State Supreme Court until a separate building for the judiciary was constructed nearby in 1913.

On reviewing proposals, the Board of Capitol Building Commissioners unanimously selected as capitol architects a Portland firm established by the German-born Justus F. Krumbein and W.G. Gilbert. Following the initial legislative appropriation of $100,000, construction was begun in 1873 with excavation aided by convict labor from the state penitentiary, which also produced the brick. Krumbein & Gilbert had projected the cost of construction at $550,000, but some expense was spared with simplification of the scheme.

Through twenty years of development, as appropriations were made for completion, repairs, and improvements, architects W.W. Piper, Wilbur F. Boothby, and Delos D. Neer were placed in charge of work at the capitol at different times. In 1892, Justus Krumbein was re-employed to modify and oversee construction of the dome.

The capitol was cruciform in plan. The length of the main building extended 264 feet from north to south and terminated in corner pavilions at either end. Minor arms serving as entrance wings were centered on west and east facades. In front of temple-fronted porticoes, grand staircases rose above the ground story of rusticated ashlar (squared building stone) to the principal floor, where the Senate and House chambers were located in opposing main wings.

Essential details of the formally composed exterior included colossal two-story stuccoed brick pilasters and portico columns of the Roman composite order, which rose to a full Classical entablature (the horizontal beam spanning the columns) that included a bracketed cornice of sheet iron. The seal of the State of Oregon was displayed in pediments (triangular areas over the cornice) of the entrance porticoes. Arched windows and doorways of the upper stories had varied pedimented frames of limestone. Wrought iron girders were used in the building’s framing. Cast iron was used in the dome and decorative elements, and enclosed steel lattice girders supported the dome.

The high, hemispherical copper-clad dome rested on a drum and single-story lantern that gave natural light to the rotunda beneath. Surmounting the dome was a cupola from which people could gain panoramic views of the surrounding valley. At its pinnacle, the capitol dome was reported to reach 190 feet above the ground, a record height among the city’s buildings.

The building had been the seat of representative government through a period of intense agitation for electoral and social reforms. Oregon’s early adoption of direct legislation by popular vote (initiative and referendum in 1902 and direct presidential primary in 1904) identified the state with Progressive politics. Subsequent direct legislation, including equal suffrage (1912), secured the state’s prominence in the Progressive reform movement. A notable example of the legislature’s deliberations in the same period was the bill passed in 1903 to limit working hours for women in industry to a ten-hour day. When challenged through the courts, the act became a landmark in constitutional case law (upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in Muller v. Oregon, 1908).

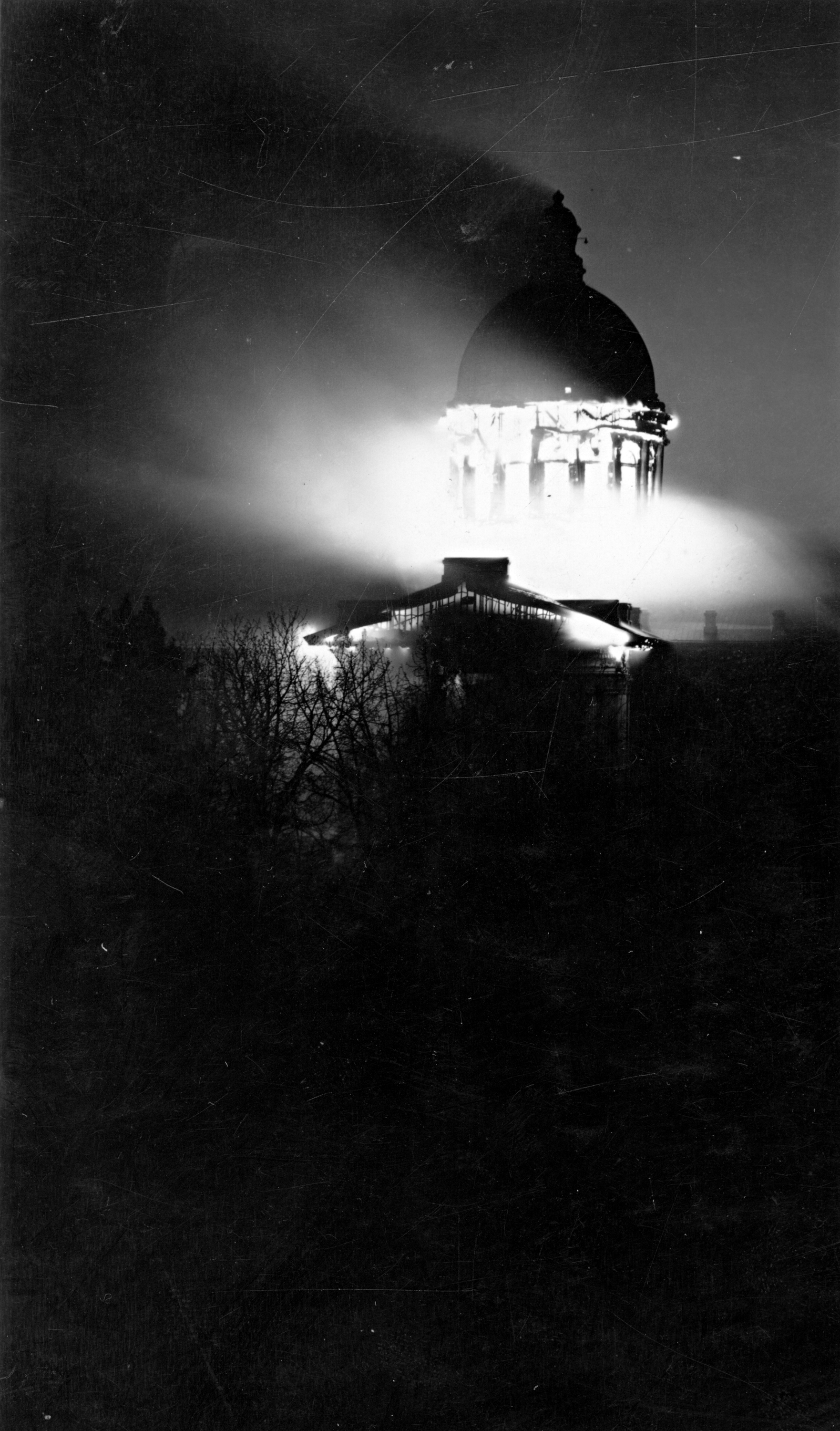

The state house served the varied branches and departments of government for fifty-eight years until, on the night of April 25, 1935, it was destroyed by a quickly-spreading fire drawn from the bottom story up through dome-supporting column shafts to break out in a spectacular blaze. Although an investigation failed to pinpoint the exact cause, it was generally believed the fire was accidental and that it originated in the storeroom-service area in the basement of the east entrance wing.

In the aftermath of the fire, officials promptly laid plans for a new building. The Modernistic present-day capitol was dedicated in 1938 following reconfiguration of the neighborhood for a north-extending mall that would accommodate inevitable expansion of Oregon state government in the years to come.

-

![1876 Oregon Capitol Building, Salem.]()

Salem, old capitol bldg, OrHi 62727.

1876 Oregon Capitol Building, Salem. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 62727

-

![Looking west at city of Salem from Oregon State Capitol building, 1920.]()

Salem, view of, from capitol bldg, 1920.

Looking west at city of Salem from Oregon State Capitol building, 1920. Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Gerald W. Williams Collec., Willamette Valley album, WilliamsG:WV Salem view

-

![Ray Stormont and John Gordon in front of Oregon State Capitol during bicycle trip from Portland to New York.]()

Salem, Capitol, bikes at, OrHi 17929-A.

Ray Stormont and John Gordon in front of Oregon State Capitol during bicycle trip from Portland to New York. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 17929-A

-

![Oregon State Capital Building, Salem.]()

Salem, capitol bldg, 0173 G 047.

Oregon State Capital Building, Salem. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 0173 G 047

-

![Fire of April 25, 1935, destroyed the 1876 Oregon State Capitol building.]()

Salem, Capitol, on fire, OrHi 5420-5421.

Fire of April 25, 1935, destroyed the 1876 Oregon State Capitol building. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 5420-5421

-

![Breyman Fountain and Oregon State Capitol, Salem, 1906.]()

Salem, old capitol bldg and Breyman Fountain.

Breyman Fountain and Oregon State Capitol, Salem, 1906. Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Gerald W. Williams Collec., Willamette Valley album, WilliamsG:WV Breyman fountain

Related Entries

-

![City of Salem]()

City of Salem

Salem, the capital of Oregon, is located at a crossroads of trade and t…

-

![Oregon State Capitol]()

Oregon State Capitol

Among capitol buildings in the United States, the Oregon State Capitol …

-

![Oregon Supreme Court Building]()

Oregon Supreme Court Building

The Oregon Supreme Court Building, at the corner of State and 12th Stre…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Barber, Joel Conrad. “A History of the Old State Capitol Buildings of the State of Oregon, 1841-1935.” MA thesis, University of Oregon, June 1966.

Bentson, William Allen. Historic Capitols of Oregon: An Illustrated History. Salem: Oregon State Library Foundation, 1987.

Hawkins, William J., III. “Justus Krumbein, Architect, 1847-1907.” Portland Friends of Cast-Iron Architecture Newsletter 16 (ca. June 1980).

Jansson, Kyle. “The Fury on the Night of Kismet.” Historic Marion (The Marion County Historical Society Quarterly) 39:2 (Summer 2001), 11-15.

Ritz, Richard Ellison. Architects of Oregon: A Biographical Dictionary of Architects Deceased – 19th and 20th Centuries. Portland, Ore.: Lair Hill Publishing, 2002.