Portland's commission form of municipal government, which the city adopted as a progressive innovation in 1913, was a rarity and relic by the twenty-first century. Despite Portland’s reputation for innovation in other realms, voters for more than a century stubbornly stuck with the basic structure in which a small set of elected officials serve simultaneously as the executives of city bureaus and as the city's legislative body. In 2022, however, they reversed course by approving sweeping city charter amendments that did away with the system.

Portland voters opted for a commission government at a time of rapid growth (especially after 1905) and criticism of city government. The mayor-council system was vulnerable to corruption and inefficiency, and the administration of Harry Lane (1905-1909) had demonstrated that electing a reform-minded mayor was not a solution. An entrenched city council consistently could block the mayor’s initiatives.

In 1912, during Allen G. Rushlight’s mayoral term (1911-1913), the Portland Vice Commission reported that four hundred downtown hotels and apartment buildings were involved in illicit sexual activity. The next year, the New York Bureau of Municipal Research—invited to Portland by leading businessmen, including Oregon Journal publisher Sam Jackson—offered a detailed and devastating critique of Portland’s operating departments in local government. Several competing reform proposals surfaced, to be winnowed to the option favored by the civic-minded business community.

A new charter mandating a commission government passed in May 1913 by a scant margin of 292 votes out of 34,342 cast. Opposition came from the local Republican Party machine, which had benefitted from the status quo. Support came from Roosevelt Progressives, downtown businesses, and the middle class of homeowners, small businessmen, professionals, and skilled workers in the new neighborhoods on the city’s east side.

Commission government blends legislative and executive functions. Voters choose a mayor and four commissioners to serve four-year terms (the commissioner terms are staggered). Elections are nonpartisan and citywide, with all five commissioners (the mayor is considered the fifth commissioner) representing the city as a whole. Sitting together, the five commissioners form the City Council to enact ordinances and serve as the legislative decision-making body. Each of the five is the chief executive of a set of city operating departments and bureaus, such as parks, police, and transportation. Voters also elect an independent city auditor, an office that has become increasingly active as a watchdog.

The commission form of government was devised in Galveston, Texas, after that city’s devastating 1900 hurricane. The idea was to allow voters to choose experienced business and professional people who could run city affairs more efficiently than political hacks. As the system has evolved in Portland, the mayor and commissioners confine themselves to questions of policy and rely on professional administrators to oversee most operations.

A frequent complaint about the system is that the division of bureaus among the five commissioners leads to turf wars and horse-trading that can override a uniform vision or policy for the city. This problem can be obviated to some degree by the authority of the mayor to define and propose the annual budget and to control the assignment of bureaus.

A second criticism is that citywide elections, with no council districts, tilt the playing field toward well-connected members of the civic-commercial leadership community who have the ability to raise campaign funds, thereby stifling the voices of minorities and poorer neighborhoods. From 1914 through 2022, only three Black men, one Black woman, and one Latina, were elected as city commissioners. Three women served as mayor under the commission system out of sixteen mayors total)—Dorothy McCullough Lee (1949-1952), Connie McCready (1979-1980), and Vera Katz (1993-2004). Seven other women have served as commissioners. Geographic concentration is variable. For example, four of five City Council members in 2017 lived on the west side of the Willamette River, but in the mid-1970s, four of five lived in the well-to-do Irvington-Alameda-Grant Park neighborhoods in northeast Portland.

Efforts to get rid of the commission government in Portland failed repeatedly. In 1950, an attempt to shift to a council-manager system, backed by Mayor Lee, failed to make the ballot. In 1958, voters rejected council-manager government by a relatively narrow 6 percent margin. Voters in 1966 crushed a proposal for a strong mayor-council system (62-38 percent) and, in 1974, soundly rejected a plan to consolidate Portland, Multnomah County, and east county suburbs into a single municipality. A proposal for a strong mayor system with an expanded city council elected by districts failed at the polls in 2002, as did a 2007 proposal to centralize administrative authority in a strong mayor and limit the four commissioners to legislative duties. Voters long saw a municipality that worked reasonably well and that offered multiple points for citizen input.

Two factors combined to bring a rapid change in public opinion. One was the growing size and political activism of Portland’s nonwhite communities and their perception that at-large elections diluted their voices and concerns. The second was the apparent inability of the city government to respond nimbly and effectively to address increases in crime and visible homelessness in the early 2020s. In November 2022, voters scrapped the 110-year-old commission system by a margin of 57 percent to 43 percent.

-

![]()

Portland City Hall, c.1914.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 002143

-

![]()

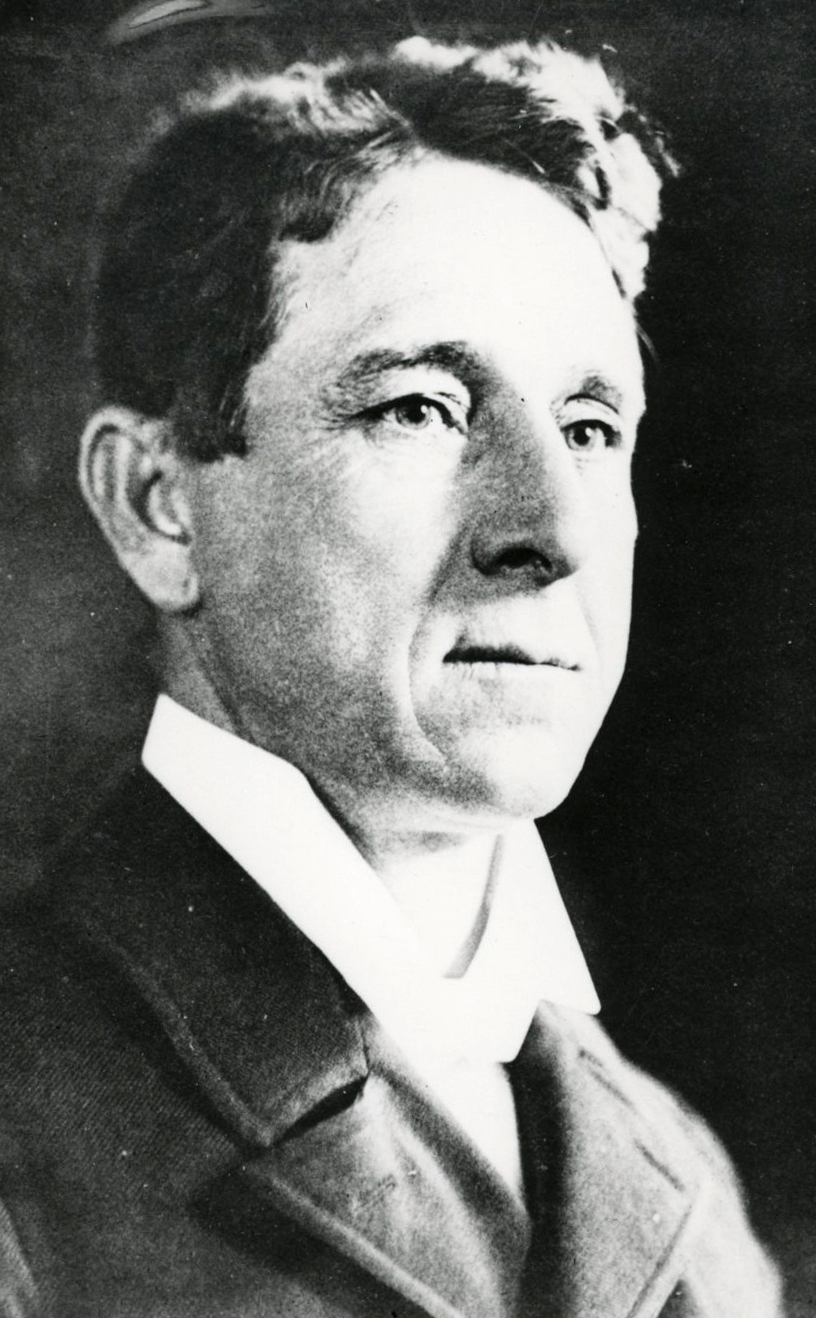

Mayor Harry Lane.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 009120

-

![]()

C.S. "Sam" Jackson.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 020681

-

![Mayor (1911-1913)]()

Mayor A.G. Rushlight, c.1910.

Mayor (1911-1913)

-

![]()

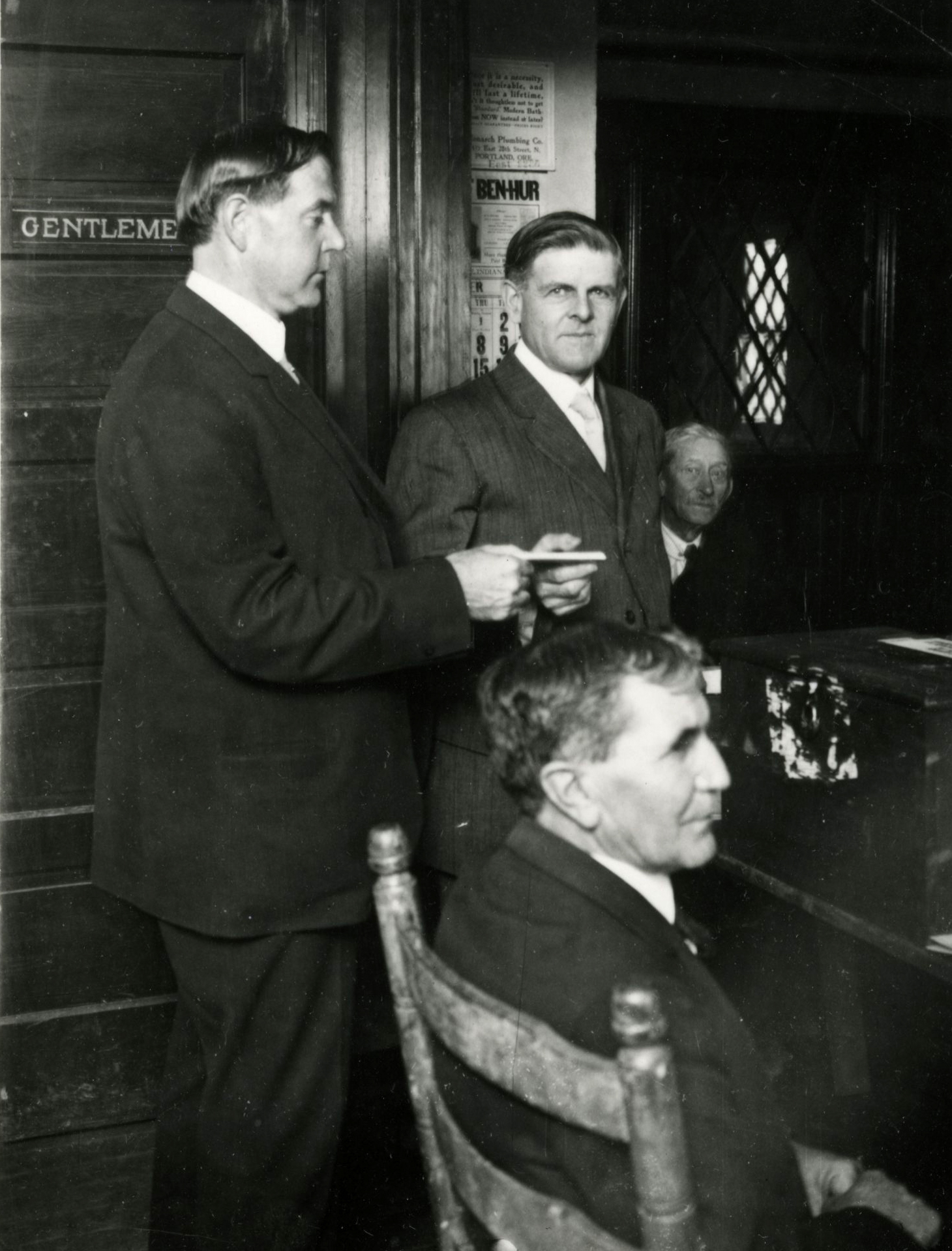

Mayor Rushlight (l) and Mayor H.R. Albee, c.1913.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 023696

-

![L-R: Ormond Bean, Kenneth Cooper, Fred Peterson, William Bowes, and Mayor Dorothy McCullough Lee]()

Portland City Commission, 1949.

L-R: Ormond Bean, Kenneth Cooper, Fred Peterson, William Bowes, and Mayor Dorothy McCullough Lee Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 008915

-

![Commissioner (1967-1980)

Mayor (1980-1985)]()

Frank Ivancie.

Commissioner (1967-1980) Mayor (1980-1985) Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi102698

-

![Commissioner (1970-1979)

Mayor (1979-1980)]()

Connie McCready.

Commissioner (1970-1979) Mayor (1979-1980) Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 691, Box 1 f6

-

![Commissioner (1972-1987)]()

Mildred Schwab.

Commissioner (1972-1987) Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 691, Box 1 f1

-

![Commissioner (1974-1984)]()

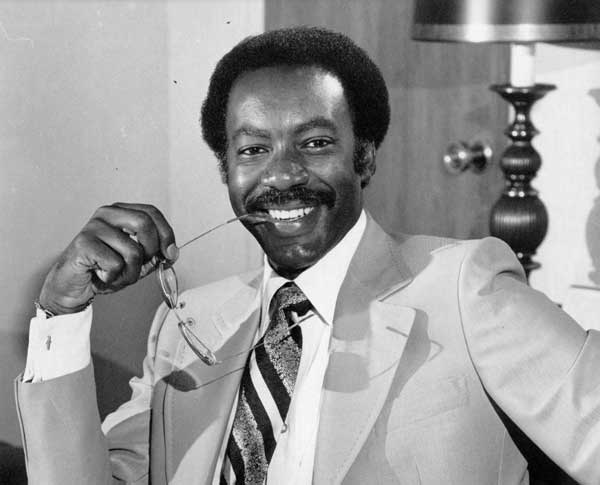

Charles Jordan, 1976.

Commissioner (1974-1984) Courtesy City of Portland, A2001-081

-

![Commissioner (1981-1986)]()

Margaret Strachen.

Commissioner (1981-1986) Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb005086

-

![Commissioner (1982-1986)]()

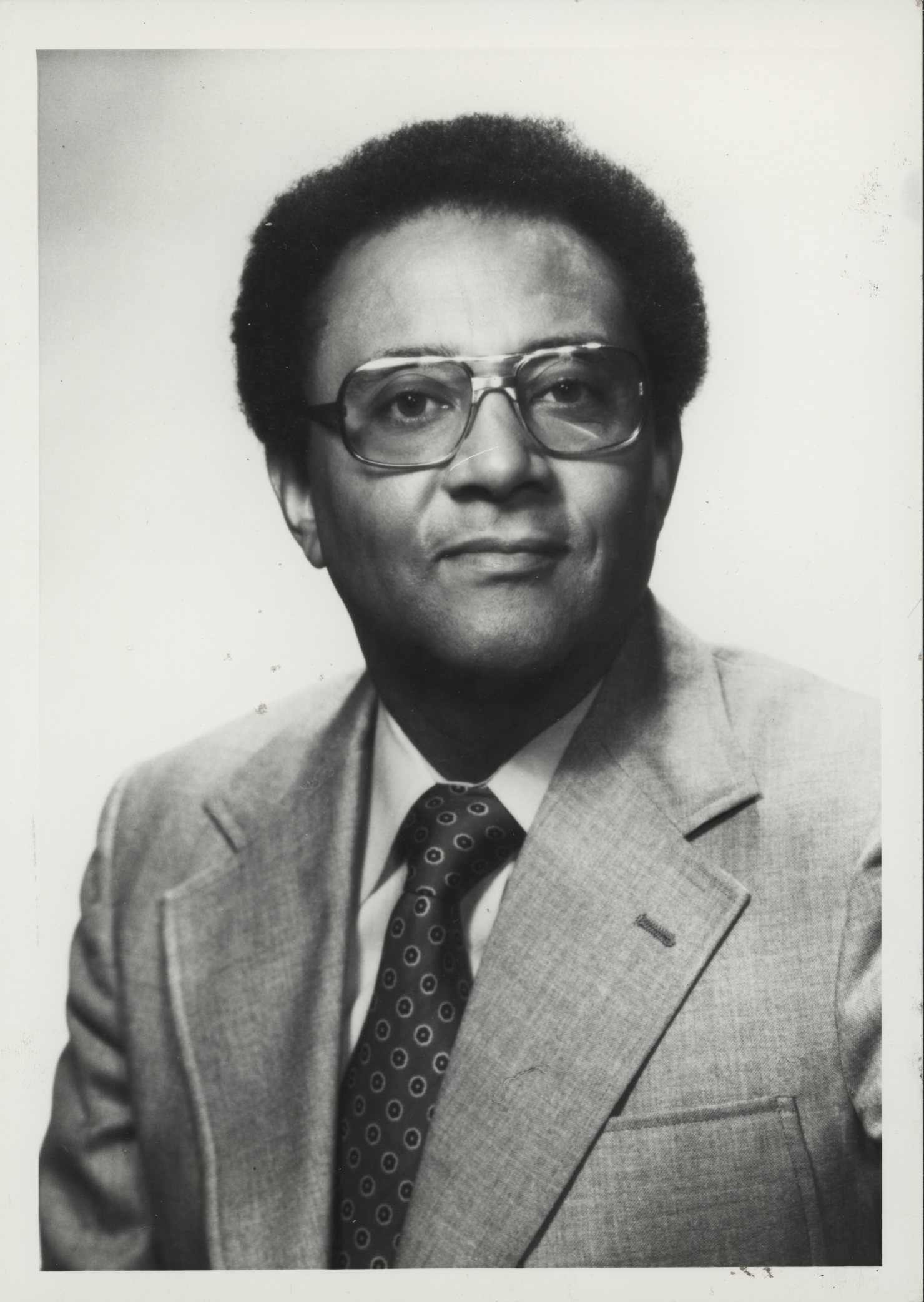

Richard Bogle.

Commissioner (1982-1986) Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bd000442

-

![Mayor (1985-1992)]()

Mayor Bud Clark (seated), 1986.

Mayor (1985-1992) Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 691, Box 1 f4

-

![Mayor (1993-2005)]()

Vera Katz.

Mayor (1993-2005) Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi104781

Related Entries

-

![Charles S. (Sam) Jackson (1860-1924)]()

Charles S. (Sam) Jackson (1860-1924)

Charles S. “Sam” Jackson, born in Virginia on September 15, 1860, came …

-

![Constance Averill McCready (1921–2000)]()

Constance Averill McCready (1921–2000)

Connie McCready was the second woman to serve as mayor of Portland, at …

-

![Dorothy McCullough Lee (1902-1981)]()

Dorothy McCullough Lee (1902-1981)

In 1947, the city of Portland crawled with gambling halls, strip joints…

-

Harry Lane (1855-1917)

Harry Lane epitomized the spirit and activism of Oregon’s progressive r…

-

![Portland]()

Portland

Portland, with a 2020 population of 652,503 within its city limits and …

-

![Portland Vice Scandal (1912-1913)]()

Portland Vice Scandal (1912-1913)

On November 8, 1912, Portland police arrested nineteen-year-old Benjami…

-

![Vera Katz (1933–2017)]()

Vera Katz (1933–2017)

Once dubbed a "militant housewife" by the Oregonian, Vera Katz arrived …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Lansing, Jewell. Portland: People, Politics and Power. Corvallis: Oregon State Univ. Press, 2005.

Johnston, Robert. The Radical Middle Class: Populist Democracy and the Question of Capitalism in Progressive Era Portland, Oregon. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press, 2006.