The repurposing and reuse of buildings in Portland have their roots in the earliest days of the city, but it was not until after World War II that the practice of building renovation and conservation grew into a movement. By the 1940s, a market for used building materials developed that continues to this day, and while the principal interest of this industry is economic, it has also embraced nostalgia and the recognition that keeping used building materials away from the landfill has a positive effect on the environment.

By the 1970s, the historic preservation movement recognized that building reuse, rather than new construction, reduced carbon emissions; yet it was not until the later part of the twentieth century that this became more widely accepted by architects, engineers, and others in the building industry. In the twenty-first century, it is just as common for Portland buildings of all shapes and sizes to be renovated or repurposed as it is for them to be demolished or deconstructed.

As the population of Portland grew from the late nineteenth and into the early twentieth century, it was common to see houses and even small commercial buildings relocated for their continued use and occupancy elsewhere. This was particularly true of smaller buildings in the downtown area that could easily be lifted onto logs or wheels and pulled to a new site using horses. The residence of Capt. Nathaniel Crosby, believed to have been the first wood-framed house constructed in Portland, in about 1847, served as a plumbers' supply and tailor shop and was moved at least once before being demolished in about 1920. In 1883, Philip A. Marquam relocated the three-story Central School building from the present site of Pioneer Courthouse Square to another property he owned one block north, at Southwest Sixth and Alder Street. The old school was repurposed with storefronts, offices, and tenement-style housing until it was demolished to build the Selling Building, completed in 1910.

At the turn of the twentieth century, it made both economic and practical sense to move and repurpose buildings in Portland. When a property owner decided to build something new and bigger or to redevelop land for another purpose altogether, it was not uncommon to see a building moved. There appear to have been few restrictions on building relocation at the time and little concern about how a building move might affect infrastructure, such as telephone or electric wires, or trees. St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church, for example, occupied a small wood-framed chapel on property acquired by the City of Portland for a new City Hall. The church was subsequently moved to Southwest Thirteenth Avenue and Clay Street, thereby keeping the church close to its parishioners and likely saving the church a significant sum of money in new building costs.

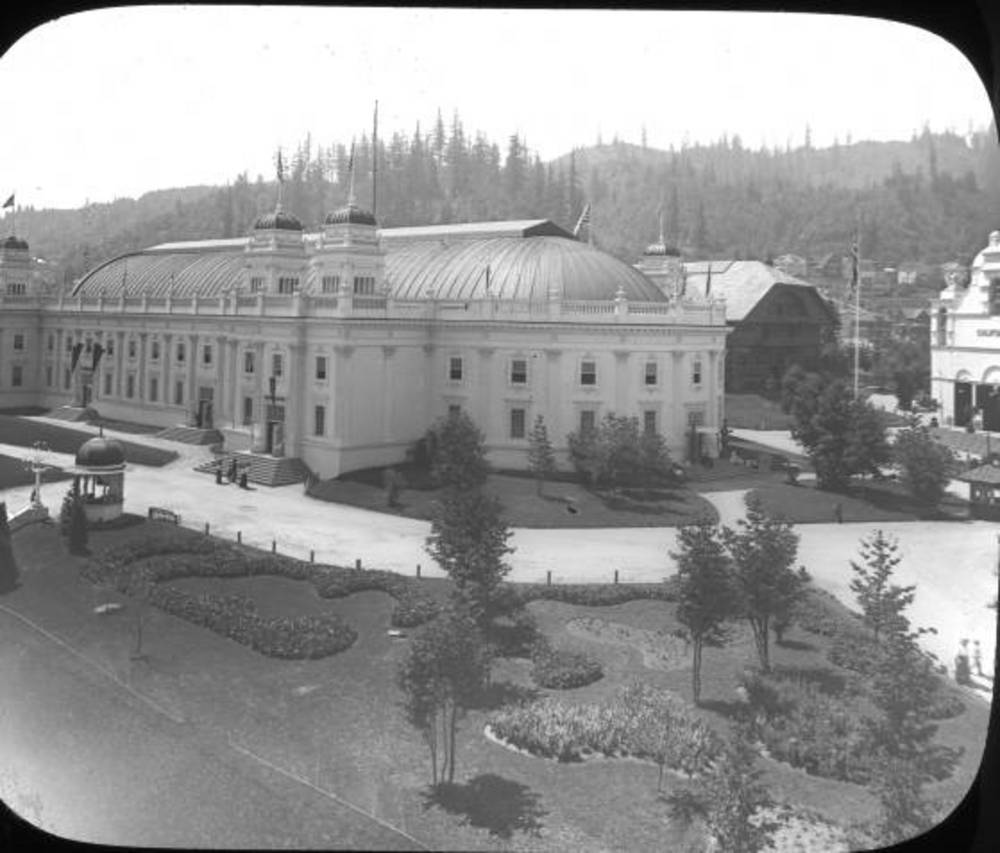

Several buildings or parts of buildings constructed in Northwest Portland for the 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition were moved elsewhere after the fair closed. The National Cash Register building, for example, was moved to the St. Johns neighborhood in 1906 and is now the St. Johns Theater and Pub. The American Inn condominium building on Northrup Street was constructed from parts of a much larger fairground hotel just a mile away. A few other buildings from the Expo were relocated, but most had been designed as temporary structures. While many of the materials used in Expo buildings went to the landfill, there was enough that was reusable that it helped fuel a new industry in Portland—building wrecking.

The Wrecking Industry

The city boomed during the decade or so after the fair. Portland’s downtown expanded, and new neighborhoods and commercial districts were developed. Fire and building codes emphasized new construction, which meant that fewer buildings were moved or repurposed. The demolition of buildings was led by so-called wrecking companies that recognized they could resell much of what they salvaged from their demolition work. In newspaper advertisements, Portland building wreckers noted the volume of material salvaged from Exposition buildings and available for resale. In 1910, the Portland Wrecking Company advertised that it had two million feet of lumber for sale, along with brick and plumbing products from several Exposition buildings.

The wrecking industry grew throughout the Depression and into the 1940s. The owners of older downtown commercial buildings found that more profit was to be found in parking lots than in rents in the increasingly stagnant central city, beginning a trend that would last until the early 1970s when a cap was placed on downtown parking spaces. In late 1941, for example, the Dolan Wrecking Company advertised that it had more than two million bricks for sale, several thousand feet of linoleum flooring, and five hundred washbasins salvaged from its recent demolition of the Worcester Block on Southwest Third Avenue. Half of the property where the 200-foot-long Worcester Block stood became a parking garage that was still in use in 2022.

Historic Preservation and Salvage

During the early 1940s, many of the city’s finest examples of cast-iron-fronted buildings near the downtown waterfront were demolished to make way for the expansion of Front Avenue (now Naito Parkway) and the construction of Harbor Drive. The destruction led some Portlanders to publicly lament the loss of buildings that others considered to be obsolete and to acknowledge that Portland’s architecture had matured enough to have a history worthy of recognition. Despite these realizations, it was still several more years before historic preservation in Portland began to gain a foothold. In about 1950, Eric Ladd began a career that would influence a generation of Portlanders who valued the city’s history and recognized monetary value in used building parts.

A native Portlander, Ladd (born Leslie Hansen) became interested in historic preservation while living in New York in the late 1940s. After returning to Portland, he moved the Jacob Kamm house, built in 1872, from Salmon Street and Eighteenth Avenue (the site of Lincoln High School, demolished in 2022) several blocks west to Southwest Twentieth Avenue, just south of Jefferson Street in the Goose Hollow neighborhood. He also moved the Illinois State Building, a replica of Abraham Lincoln’s boyhood home built for the Lewis and Clark Exposition, from Northwest Twenty-Sixth Avenue and Nicolai Street to a property adjacent to the Kamm House as part of what he called his “Colony.” After sustaining heavy damage in a fire, the Lincoln House was later demolished, but the Kamm House remains one of Portland’s most important architectural landmarks.

Ladd also salvaged pieces from other historic, but demolished, Portland buildings. Terracotta ornaments from the 1892 Oregonian Tower, the former chapel for St. Mary’s School, and pieces from a dozen or so cast-iron-fronted buildings made their way to Ladd’s Colony. He also determined that there was money to be made in reusing salvage from old buildings. Before the elegant former home of Richard and Minnie Knapp was demolished in 1951, he ran a sale at the house that included furnishings but also pieces of the house itself. He salvaged a significant amount of material for himself and outfitted a room in his Kamm house, which he opened as the Kamm House Restaurant in 1955.

Ladd’s interest in historic preservation, salvage, and profitable building parts influenced other Portlanders. In the mid-1950s, teenager Jerry Bosco began buying and salvaging pieces from demolished houses in the neighborhood being redeveloped as the Lloyd Center. His earliest salvage included stained glass windows that he bought for ten dollars from a house that had been the Battleship Oregon Museum. By the end of the 1960s, Bosco and his partner Ben Milligan were salvaging pieces of demolished Portland houses and other buildings. They renovated a pair of Victorian-era houses they owned in southeast Portland’s Sunnyside neighborhood and restored plaster and stained glass for clients. Opening one of the houses as Victorian Facades, they sold used building parts in the shop. Before their deaths in the late 1980s, Bosco and Milligan would go on to found the nonprofit Bosco-Milligan Foundation, which operates the Architectural Heritage Center in Portland’s Central Eastside.

In 1963, Elizabeth Fowler opened 1874 House on Southwest Thirteenth Avenue. Both the house and nearby St. Helen’s Hall (a school that became Oregon Episcopal School in 1972) were in the path of Interstate 405 and scheduled for demolition. Fowler acquired pieces of the two buildings from wreckers and set up the shop as a fundraiser for the school. After the buildings were demolished, she moved 1874 House to Southeast Thirteenth Avenue in the Sellwood neighborhood. By the 1970s, Southeast Thirteenth was popular as Antique Row.

Beginning in the 1970s, Bill and Sam Naito bought and restored over twenty historic buildings in Portland, including Montgomery Park and the Olds, Wortman & King Building. The Naitos purchased the historic Albers Mill Building and transformed it into office space; they helped move the Simon Benson House in 2000 to Portland State University after it was condemned to demolition; and they renovated the Natural Capital Center building (1895) in the Pearl with spaces for Ecotrust and Patagonia. Their impact on historical renovation and salvage was recognized by the city in 1996 when Front Street was renamed Naito Parkway.

The influence of Bosco and Milligan, Fowler, Ladd, the Naitos, and the building wreckers who were selling building parts in the early twentieth century continued. Rejuvenation Inc. was founded in 1977 by Jim Kelly and Barbara Kerr, both acquaintances of Bosco and Milligan. The store sold antique doorknobs and other hardware and became known for its reproduction lighting. Before the company was sold to Williams-Sonoma in 2011, Rejuvenation’s southeast Portland store was also a source for used building parts, including doors, windows, and plumbing and light fixtures.

Taking a cue from Bosco and Milligan, representatives of Rejuvenation and Aurora Mills Architectural Salvage, founded in Aurora in 1999, began touring the country in search of building salvage they could resell as the supply in Portland began to wane. From the 1960s into the early 2000s, budget-conscious homeowners could spruce up their older homes by buying parts from stores like Rejuvenation or Hippo Hardware, founded on East Burnside in 1976. It was also during this period that a do-it-yourself ethic embraced the idea of reuse as an important tenet of environmental sustainability. In the twenty-first century, reuse remains a way to keep old building parts out of landfills. At the same time, however, concerns over hazardous materials such as lead paint and asbestos made it increasingly difficult for do-it-yourselfers to find affordable and usable old building parts.

In recent years, an increased desire to reduce the environmental impact of new construction led to the remodel and reuse of several large downtown buildings, including the 1982 Portland Building and the 1974 Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt Federal Building, which was thoroughly transformed in the early 2010s from a concrete box into one of the most energy efficient buildings in the city.

In 2022, it is common to see Portland area buildings renovated, but far less so to see one relocated. Permits, fees, and the presence of other infrastructure, like overhead light rail and streetcar lines, make the cost of moving a building prohibitive in most circumstances. In recent years, however, there have been a few important buildings that were relocated and repurposed. In 2007, the 1883 Ladd Carriage House, a horse stable for William S. Ladd that was later used as an office building, was moved from Southwest Broadway and Columbia Street during construction of an underground parking garage and apartment tower. The building was returned to its original location in 2008 and thoroughly renovated the following year.

In 2017, Karen Karlsson and Rick Michaelson moved the 1880 Fried-Durkheimer House (also known as the Morris Marks House) from Southwest Twelfth Avenue to a lot at the end of Southwest Broadway, where it was substantially renovated. Michaelson has been involved in other historic building moves dating back to the 1970s. While such relocations are unusual, the building salvage industry continues to flourish, selling pieces to those who want to reduce the impact of new construction and also live with a touch of Portland history.

-

National Cash Register Building, 1905.

City of Portland Oregon Archives, A2004-002.290 -

![]()

YMCA in 1932 on N. Ivanhoe and Richmond, former National Cash Register building, now St. John's Pub.

Courtesy Portland City Archives -

![]()

McMenamins St. Johns Theater & Pub, formerly the National Cash Register building.

Courtesy McMenamins

-

![]()

American Inn, Lewis and Clark Expo, 1905.

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries -

![]()

American Inn Condos, Portland.

Google maps

-

![]()

Worcester Building, Portland, 1939.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrgLot52_390318-7 -

![]()

Downtown Portland and Waterfront, c.1920.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrgLot78_B1F17_012 -

![]()

Harbor Drive, along former waterfront business district on west side, Portland, 1955.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, OrgLot1284_2527_4 -

![]()

Waterfront Park, which replaced Harbor Drive, in Portland, 1970s.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., ba018326

-

![]()

Kamm House, SW Fourteenth and Main, March 27, 1939.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi9344

-

![]()

Jerry Bosco and Ben Milligan, 1979.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi96251

-

![]()

Architectural Heritage Center, Portland.

Courtesy Architectural Heritage Center -

![]()

-

![]()

Montgomery Ward building, 1920.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Digital Collections, Oregon Journal, Org. Lot 1368: Box 376; 376G0323

-

![]()

-

![]()

Olds, Wortman, & King Department Store, Portland.

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries -

![]()

Galleria, former Olds, Wortman & King Building.

Courtesy Lost Portland, Molly J. Smith -

![]()

Simon Benson House.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org. Lot. 472, box 1, f21

-

Simon Benson House, NE ext, Oct 19 2011.

Simon Benson House on Portland State University campus, Oct. 2011. Photo James V. Hillegas

-

![]()

Albers Bros. Mill on NW Front Ave. (Naito Pkwy), Portland. Broadway Bridge in background..

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries

-

![Portland Building]()

Portland Building.

Portland Building Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries, pna_19482

-

![]()

Ladd Carriage House.

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries -

![]()

Marks, Morris, House, Portland.

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries

Related Entries

-

![Bosco-Milligan Foundation]()

Bosco-Milligan Foundation

The Bosco-Milligan Foundation of Portland was founded in 1987 by Jerry …

-

Cast iron buildings in Portland

Portland is home to the second largest collection of cast iron architec…

-

![Climate Change in Oregon]()

Climate Change in Oregon

Within a few hundred miles in Oregon, you can see snowy volcanoes, parc…

-

![Lewis and Clark Exposition]()

Lewis and Clark Exposition

Portland staged its first and only world's fair from June 1 through Oct…

-

Simon Benson House

The Simon Benson House, a Queen Anne-style house built in 1900 by timbe…

-

![William Sumio Naito (1925-1996)]()

William Sumio Naito (1925-1996)

William “Bill” Naito was born in Portland in 1925. His parents, Hide an…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Ballestrem, Val C. Lost Portland, Oregon. Charleston, SC: HIstory Press, 2018.

Hawkins, William J., III, and William F. Willingham. Classic Houses of Portland, Oregon 1850 – 1950. Portland, Ore.: Timber Press,1999.

Lindberg, James B. “Avoiding Carbon: Mitigating Climate Change Through Preservation and Reuse.” From Preservation, Sustainability, and Equity, edited by Erica Avrami. New York: Columbia University Press, 2021.

Nelson, Donald R. Progressive Portland – On The Move. Portland: 2004.