Julia Ruuttila was a labor and investigative journalist, a poet and fiction writer, and a union, peace, and justice activist who lived all but a few years of her life in Oregon.

Ruuttila was born Julia Evelyn Godman on April 26, 1907, in Eugene to John B. Godman and Ella B. Padan Godman. She was raised there, as well as on a Lane County farm and in logging camps. The Godman home was frequented by socialists, anarchists, and traveling Wobblies (members of the Industrial Workers of the World), and as a young girl she eavesdropped on their discussions and began to absorb their ideas. She was also influenced by her father’s history books and often accompanied her mother on marches for woman suffrage and when she went door-to-door distributing then-illegal birth control information.

Mostly home schooled, Julia Godman was drilled in writing, and she developed a lifelong dedication to writing poetry and fiction. Her active imagination served her well in writing fiction, but it also led her to recreate her own life story. In her later years, for example, she falsely claimed that her father was the son of a slave who had come to Oregon to “pass for white,” an apparent desire to identify with the underdog.

In 1935, as a surge of union organizing hit the nation, she was living with her husband Maurice “Butch” Bertram (and young son) at a Linnton sawmill where he was employed. The couple recruited mill workers for a woodworkers’ union, and she founded and headed the ladies’ auxiliary. In 1937, the union left the AFL for the CIO and became the International Woodworkers of America (IWA), precipitating an eight and half month lock out. Under her leadership, the auxiliary successfully supported the workers and their families so they could afford to maintain solidarity until their hearing before the National Labor Relations Board, where they were successful.

In 1936, Ruuttila enlisted the support of the IWA to organize the Free Ray Becker Committee. Becker was the last Wobbly in prison following the events in Centralia, Washington, on November 11, 1919, when the American Legion and the IWW clashed and five men died. To publicize Becker’s case, she began writing for The Timberworker, the woodworker's union paper. Soon she was Oregon editor, a position she held until 1940.

In May 1948, she covered the Vanport flood for the People’s World, focusing on the inadequacies of the Portland Housing Authority and the State Public Welfare Commission’s response to flood victims. Because she was employed as a stenographer for the State Public Welfare Commission, she wrote under the pen name Kathleen Cronin. She was fired when her identity was discovered.

She then went to work for the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union (ILWU), first as a publicist during a strike and then as a secretary to the international representative for the Northwest and a stringer for The Dispatcher, the ILWU newspaper. She was also a correspondent for Federated Press, the labor and farm news service, until its demise in December 1956.

Following her 1951 marriage to Oscar Ruuttila, a warehouseman and ILWU and Communist Party activist, Julia Ruuttila moved to Astoria, where she worked for the Columbia River Fishermen's Protective Union. She organized an ILWU Ladies Auxiliary there and a Committee for Protection of Foreign Born. Though she claimed not to have joined the Communist Party herself, she was subpoenaed to a House Committee on Un-American Activities hearing on Communist Political Subversion, held in Seattle in December 1956, investigating the Committee for Protection of Foreign Born.

Following Oscar’s death in 1962, Ruuttila returned to Portland, where she joined the Portland Longshore Auxiliary and served as the chair of their Legislative Committee. She was active in the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom’s campaign to prevent the transport of nerve gas to the Chemical Depot in Umatilla, protested the Vietnam War, and worked to draw the labor movement into the anti-war struggle.

Ruuttila said she had been arrested for the first time during the IWA lockout. Her last arrest was in 1975 for sitting in at the Pacific Power & Light offices in Portland in protest of electric rate hikes. When she was eighty years old, she retired from The Dispatcher and moved to Anchorage, Alaska, to live with her grandson Shane. She died there in 1991.

An honorary lifetime member of the IWA, Ruuttila was first elected a Democratic Party precinct committeewoman in 1938 and was still serving when she retired in 1987. Never forgetting her father’s history lessons, she often published labor history articles for union papers; but she was proudest of her investigative reporting, especially one exposing court ordered peonage on Sauvie Island which led to the termination of the practice.

-

![]()

Julia Godman Ruuttila, c. 1942.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi21716

-

![]()

Julia Godman Ruuttila.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi086148

-

![Julia Ruuttila at a City Council Meeting Against Violence, 1970.]()

Julia Ruuttila (center, in dark dress), 1970.

Julia Ruuttila at a City Council Meeting Against Violence, 1970. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, acc11735

-

![]()

Ruuttila at a Red Lion labor protest in 1966.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi85712

-

![]()

Julia Ruuttila being arrested at a peace march in Portland, 1966.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 23920

-

![]()

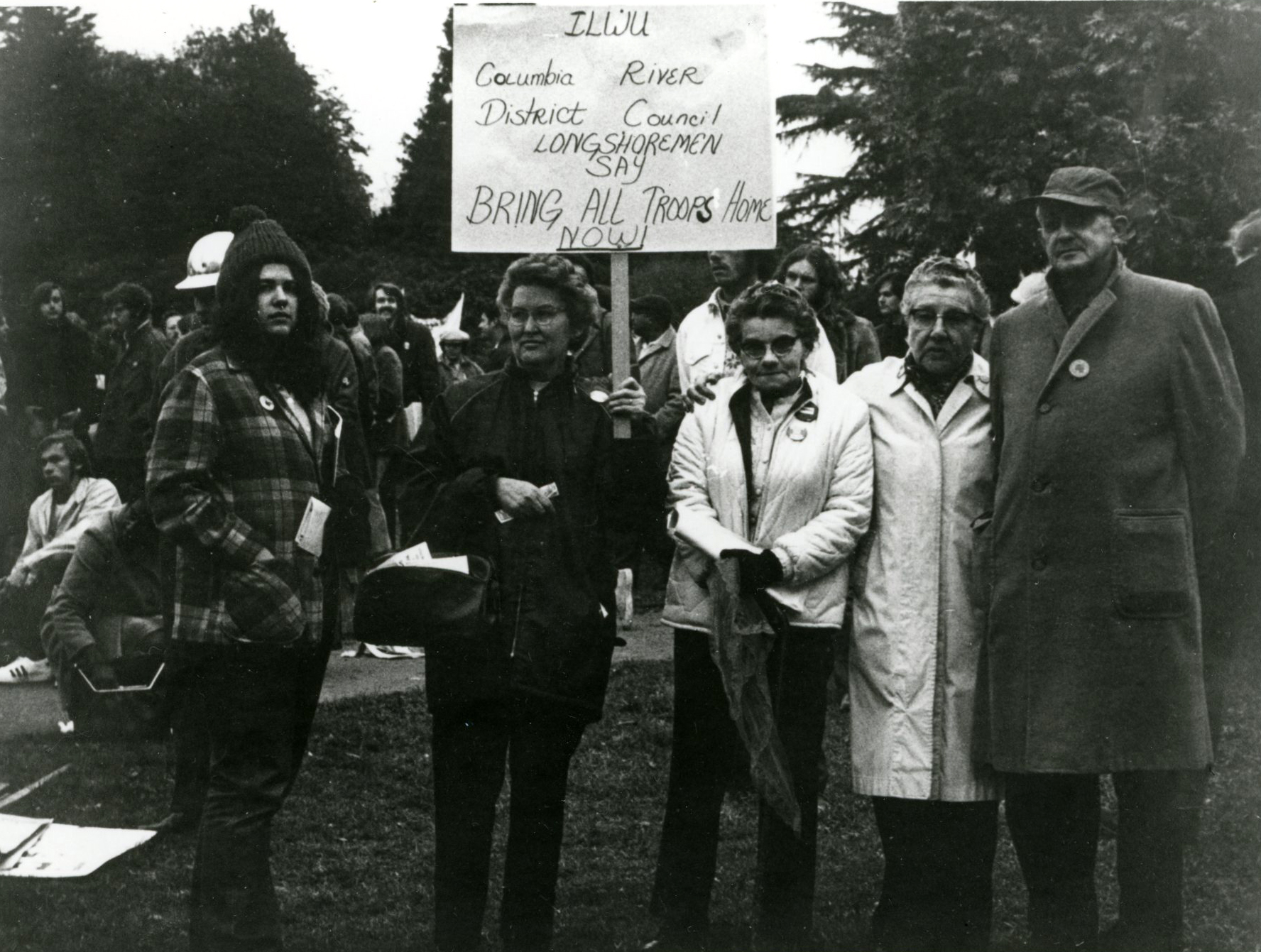

Julia Ruuttila (center) with members of the Stranahan family at a Vietnam demonstration in Seattle.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi086147

Related Entries

-

![Columbia River Fisherman's Protective Union]()

Columbia River Fisherman's Protective Union

The Columbia River Fishermen's Beneficial Aid Society was organized on …

-

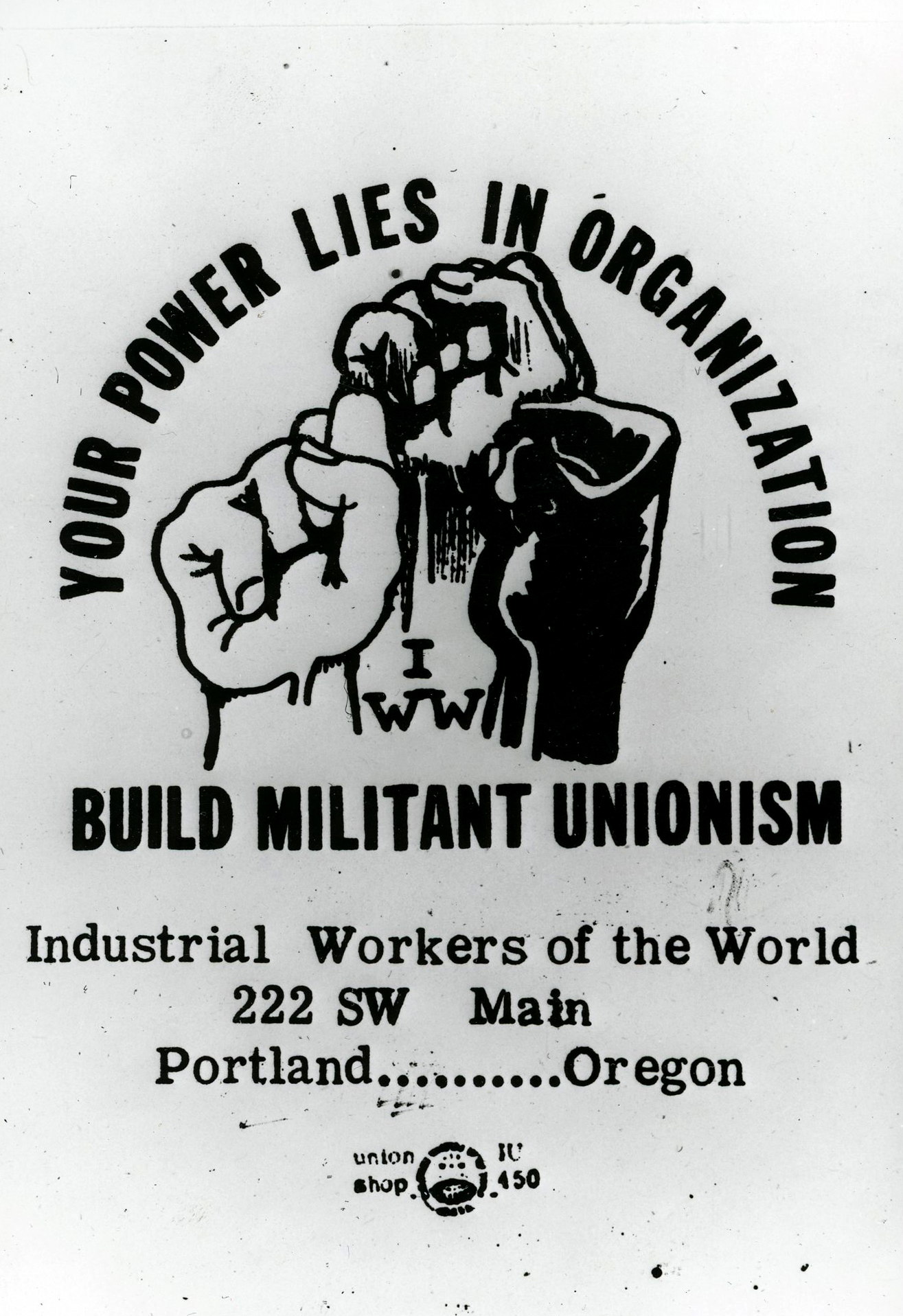

![Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)]()

Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or "Wobblies"), founded in 190…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Copeland, Tom. The Centralia Tragedy of 1919: Elmer Smith and the Wobblies. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000.

Lembcke, Jerry and William M. Tattam. One Union in Wood: A Political History of the International Woodworkers of America. New York: International, 1984.

Polishuk, Sandy. Sticking to the Union: An Oral History of the Life and Times of Julia Ruuttila. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.