James D. Saules was a Black American sailor and musician who arrived in Oregon in 1841 as part of the U.S. Exploring Expedition. He ran a freight business on the Columbia River and was known for playing the fiddle at social events. By 1843, Saules faced racist attitudes when Oregon Trail emigrants began arriving in the region in large numbers. While most Anglo-American settlers were anti-slavery, they also believed that Blacks were inherently inferior and would form a troublesome population if allowed to live among whites in Oregon. Saules may have inspired the first Black exclusion law in present-day Oregon.

Saules was probably born in 1806, although his birthplace is unknown. By the 1830s, he was living in New Haven, Connecticut, and working in the maritime industry, the largest employer of free Black men in the antebellum United States. As a mate on the whaling bark Winslow in 1833, he sailed from New Bedford, Massachusetts, to the offshore whaling grounds of the Pacific Ocean.

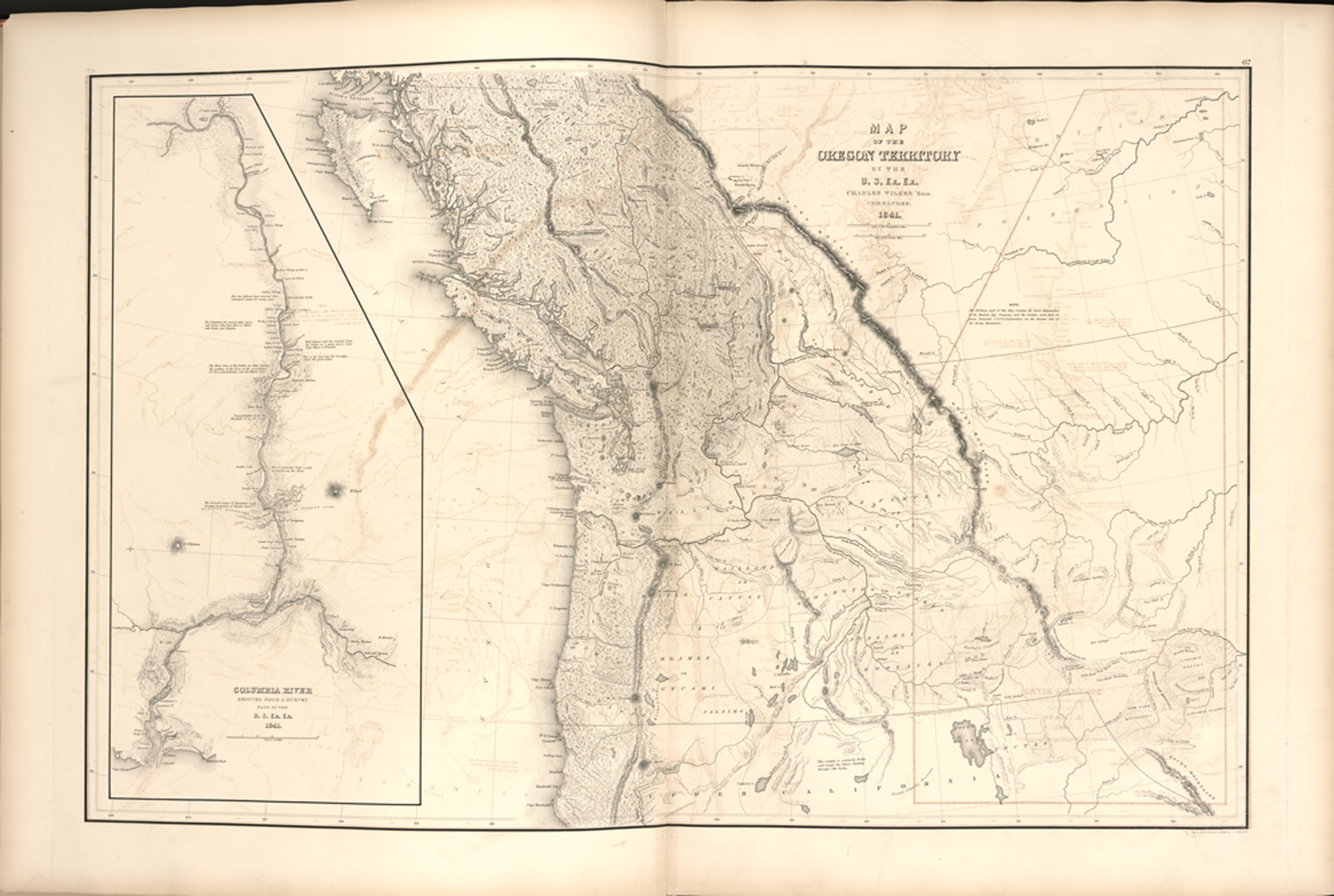

By July 1839, Saules had deserted the Winslow and was living in Callao, Peru, where he signed on to serve as ship’s cook for the U.S. Exploring Expedition (1838–1842). The U.S. Congress had created the six-vessel naval mission to explore and survey uncharted locations in the South Pole, the South Pacific, and the Pacific Northwest. Saules joined the expedition during its second year.

Saules arrived at the mouth of the Columbia River on July 17, 1841, aboard the U.S.S. Peacock, a sloop commanded by Lieutenant William L. Hudson. The following day, in an attempt to sail into the river across the treacherous Columbia Bar, the ship’s bow became submerged in sand, and waves smashed it to pieces. All 133 crewmembers survived. That October, when the expedition left the Columbia on the brig Oregon, Saules stayed behind. He married a Chinook woman, built a cabin on Cape Disappointment, and started a freight business. By early 1844 he and his wife had relocated to a farm near the nascent American community at Willamette Falls, where he was peripherally involved in what became known as the Cockstock Incident.

On May 1, 1844, Sheriff Joseph L. Meek arrested Saules for inciting several Natives to threaten the life and property of Charles E. Pickett, an erstwhile journalist and pro-slavery Virginian. Saules was tried by an all-white jury, found guilty, and handed over to Elijah White, a United States subagent of Indian Affairs, who instructed Saules to leave the Willamette Valley and relocate to Clatsop Plains. White wrote Secretary of War William Wilkins, referring to Saules and all Blacks in Oregon as “dangerous subjects” and inquiring about a ban on Black immigration. Oregon’s Provisional Government did not wait for a response from the secretary. On June 26, 1844, the legislative committee passed Oregon’s first Black exclusion law, which prescribed public flogging to any Black who came to Oregon and stayed beyond an allotted time––two years for males and three years for females.

Saules spent the rest of his life near the mouth of the Columbia River, where he witnessed growing imperial tensions between the United States and Great Britain over control of the Pacific Northwest. In September 1845, Hudson’s Bay Company Chief Factor Peter Skene Ogden arrived at Saules’s property at Cape Disappointment to purchase part of his land. Ogden was secretly working on behalf of the British government to install artillery on the cape in order to attack U.S. ships in the event of war. The deal fell through, however, when two American settlers claimed to be the land’s rightful owners. The settlers’ claim was questionable, but they succeeded in removing Saules from the land.

On July 18, 1846, the U.S.S. Shark sailed into the Columbia to project American power in the region, and Saules was hired to pilot the ship up the river. He was relieved of his duties when he guided the ship onto a sandbar. A month earlier, Britain had ceded all of Oregon south of the 49th parallel to the United States in the Oregon Treaty.

Little is known about the remainder of Saules’s life. In December 1846, he was brought before Justice Andrew Hood in Oregon City on charges of causing the death of his wife; he eventually was released from custody. He largely disappeared from the historical record after 1851, although some historians have speculated that he drowned in the Columbia River in the 1850s.

-

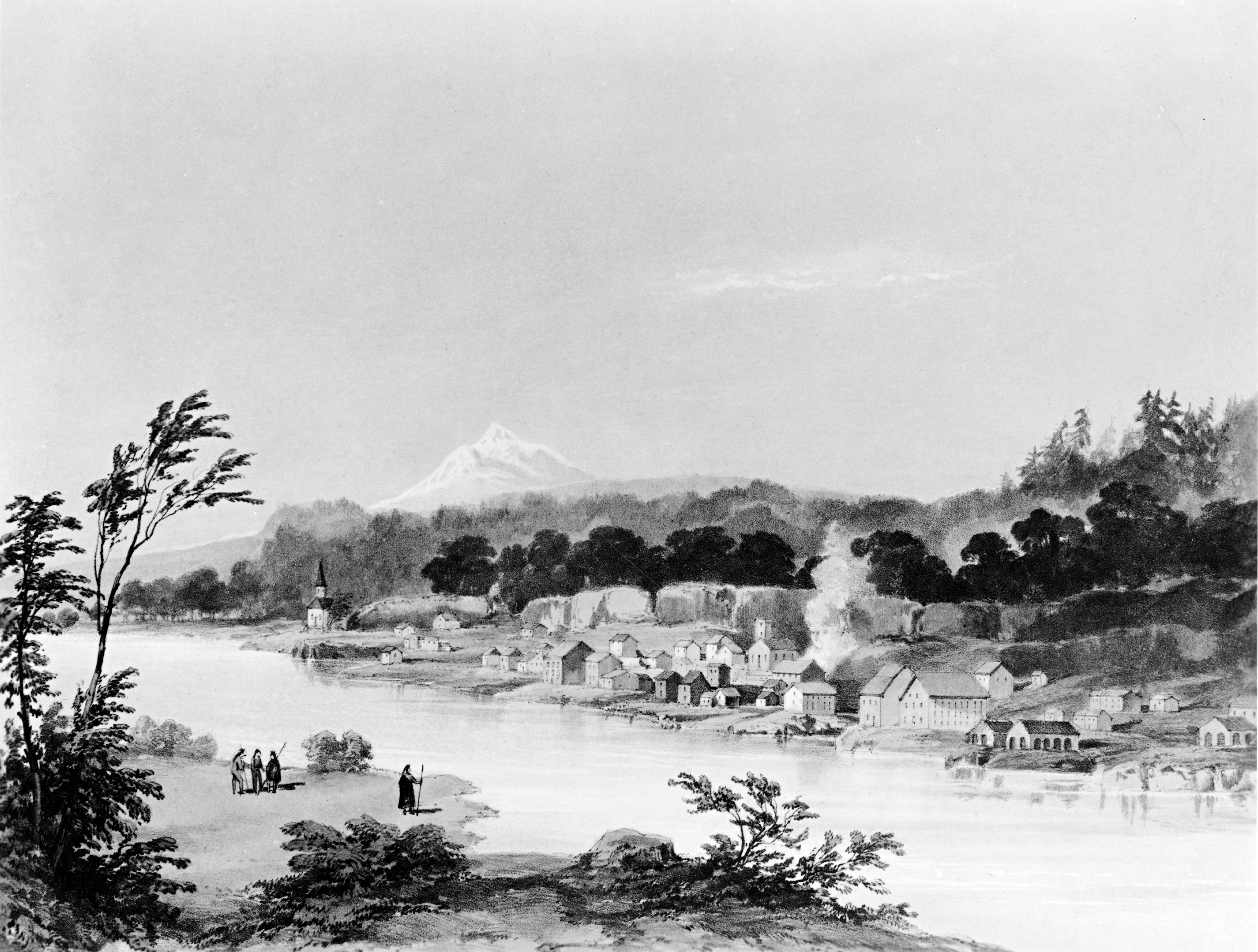

![Lithograph of Oregon City, early 1845.]()

Oregon City, 1845, ba014134.

Lithograph of Oregon City, early 1845. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., ba014134

-

![]()

The Shark on a Mediterranean Cruise, 1935-8; watercolor by Francois Roux.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 13289, photo file 1164

-

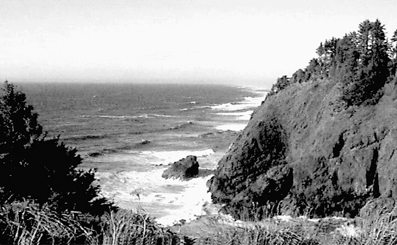

![Cape Disappointment]()

Cape Disappointment.

Cape Disappointment Courtesy Washington State Parks & Rec. Commission

-

!["Peacock contact with iceberg with Wilkes Expedition." Drawing by M. Osbourne.]()

U.S.S. Peacock.

"Peacock contact with iceberg with Wilkes Expedition." Drawing by M. Osbourne. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi91013

Related Entries

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![Cockstock Incident]()

Cockstock Incident

The Cockstock Incident in 1844, also known as the Cockstock Affair, was…

-

![Joseph L. Meek (1810–1875)]()

Joseph L. Meek (1810–1875)

Joseph L. Meek, a mountain man, storyteller, and public personality, pl…

-

![United States Exploring Expedition (1838-1842)]()

United States Exploring Expedition (1838-1842)

The United States Exploring Expedition (1838-1842), also known as the W…

-

![U.S.S. Peacock]()

U.S.S. Peacock

The U.S.S. Peacock, a ten-gun, three-masted sloop, was the first ship o…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Coleman, Kenneth R. Dangerous Subjects: James D. Saules and the Rise of Black Exclusion in Oregon. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2017.

McClintock, Thomas C. "James Saules, Peter Burnett, and the Oregon Black Exclusion Law of June 1844." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 86, no. 3 (1995): 121–130.

McLagan, Elizabeth, and Oregon Black History Project. A Peculiar Paradise: A History of Blacks in Oregon, 1778-1940. Athens, GA: Gerorgian Press, 1980.

Stanton, WIlliam Ragan. The Great United States Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975.