Indian Place was a Native community on the Necanicum River estuary in present-day Seaside, on the north Oregon Coast. Though the community was a successor to traditional settlements in the area, including Necotat and Neacoxie, Indian Place refers to a community of families that coalesced at the site throughout the nineteenth century. The village included longtime residents of Clatsop and Nehalem-Tillamook ancestry and their kin who had been displaced from traditional homelands. Ultimately situated on the Necanicum estuary's east bank, not far from the site of Necotat, the settlement became known to Seaside's non-Native residents as Indian Place, a toponym eventually adopted by many tribal members. Like the Hobsonville Indian Community on Tillamook Bay, it was among the few tribally owned and initiated reserves in Oregon.

Several events contributed to displacing Clatsop people from their traditional lands. The Hudson’s Bay Company attacked a large village at Point Adams, at the mouth of the Columbia River, in 1829; and villages were ravaged by epidemic diseases, especially during the 1830s. A presidential proclamation in 1852 slated Point Adams for military preemption, leading to the expulsion of remaining residents in 1863 during the construction of Fort Stevens. Donation Land Claims and associated EuroAmerican agricultural settlement also forced people out of many Clatsop settlements.

Families of survivors and refugees regrouped and moved in two principal directions. Some relocated north of the Columbia, joining Chinook kin at Bay Center, Washington, while others moved as far north as the Quinault Reservation on the southwestern Olympic Peninsula. Others moved south, joining refugee and resident families in Seaside or the Hobsonville Indian Community on Tillamook Bay. In time, some became part of the Grand Ronde and Siletz reservation communities.

First-person written accounts in the nineteenth century consistently describe Seaside as a place of both Clatsop and Nehalem-Tillamook heritage. Displaced families from the Columbia estuary to Tillamook Bay converged here, forging a community that organized itself along kinship networks and maintained a semblance of traditional life. Indian Place became an important center of social, ceremonial, and economic activity that was linked to a constellation of other tribal communities along the Oregon and Washington Coasts. It was also a stopover for members of many tribes traveling along the northern Oregon Coast.

Chief Kotata and Chief Dunkle were key leaders at Indian Place in the mid-nineteenth century. Both were signatories to the unratified 1851 Tansy Point treaties, which had promised the Clatsop a reservation at Point Adams and fishing rights at Seaside. Dunkle had been a signatory to the treaty between the United States and the Nehalem Band of Tillamook. Lacking a treaty reservation and resisting relocation, Kotata and Dunkle coordinated the relocation of Clatsop and Nehalem-Tillamook people within their homelands. A succession of Indian agents, typically associated with either the Grand Ronde or Siletz agencies, sometimes visited the community, but agency relationships with the off-reservation community remained murky and tenuous.

A 294-acre Donation Land Claim registered to James A. Cook in 1873 included the site of Indian Place. He sold that portion of the claim to W.J. Loomis, who then sold it to T.B. Morrison. In 1879, Morrison sold the village site to Kotata’s niece Tsin-is-tum (known as Jennie Michel) and her husband, former Hudson’s Bay Company employee Michel Martineau. Smaller tracts were sold to others, including tribal members. Tsin-is-tum and Martineau made portions of their lands available, temporarily or permanently, to tribal members who relocated there. Together, these private landholdings became a de facto reserve created and owned in fee simple title by tribal members.

Dunkle’s death in 1880 and Kotata’s in 1883 marked an end to the traditional chieftainship at Seaside, and most day-to-day management was in the hands of Tsin-is-tum and Martineau. The community maintained a complex but often congenial relationship with EuroAmerican settlers and tourists who visited the area. Indian Place residents procured and shared wild foods with white families, including shellfish, fish, meat, and strawberries. They also sold berries, clams, and firewood to the Seaside House and other inns, where some worked as domestic staff. Hoteliers sometimes hired village residents, such as Nancy Gervais, to entertain guests as storytellers.

In July 1890, anthropologist Franz Boas visited Indian Place to record Clatsop linguistic and cultural data, but he found that residents largely spoke Nehalem-Tillamook. He carried out his research with "a few of their relatives, who still continued to speak Clatsop" at Bay Center.

Indian Place also became a popular tourist destination, where visitors took photos and purchased baskets, especially those made by Tsin-is-tum. When she died in 1905, the Morning Oregonian wrote: “It is doubtful if any person, man or woman, in the State of Oregon has been photographed so frequently as has Jennie Michel.”

After Tsin-is-tum's death, most remaining tribal members moved away to tribal and nontribal communities in western Oregon and Washington, and the settlement site was overrun by residential development. History enthusiasts in Seaside twice raised funds to erect memorials at the approximate site of the village, first with a modest marker in the 1950s and then with a permanent marker in the 1980s. The modern memorial features a small plaque that commemorates the life of Tsin-is-tum but does not specifically mention Indian Place.

-

![]()

Tsin-is-tum (Jennie Michel) stands in front of an Indian Place house; the woman seated is likely De-o-so, wife of Chief Kotata..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., bb010093

-

![]()

Tsin-is-tum (Jennie Michel) stands in front of an Indian Place house; the woman seated is likely De-o-so, wife of Chief Kotata..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., bb010093

-

![]()

A sign marking Indian Place, Oregon.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., orhi75547

-

![]()

A sign marking Indian Place, Oregon.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., orhi75547

-

![]()

Section of Lewis and Clark's 1806 map of the lower Columbia, showing Pt. Adams and the Clatsop village Neak'ilaki; the future site of Indian Place is south along the coast, labeled "Clott Sopp and Ki la mox.".

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., bb010758

-

![]()

Section of Lewis and Clark's 1806 map of the lower Columbia, showing Pt. Adams and the Clatsop village Neak'ilaki; the future site of Indian Place is south along the coast, labeled "Clott Sopp and Ki la mox.".

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., bb010758

-

![]()

Hand drawn map of Indian Place by Harold Gill, 1961.

Courtesy National Park Service

-

![]()

Hand drawn map of Indian Place by Harold Gill, 1961.

Courtesy National Park Service

-

![]()

Clatsop Chief Tostom.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., bb015034

-

![]()

Clatsop Chief Tostom.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., bb015034

-

![]()

Indian Place residents: Joseph Swahaw (l), Grace (Kotata) Swahaw, Jennie Lane, Michel Martineau, and Jennie Michel.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., bb015025

-

![]()

Indian Place residents: Joseph Swahaw (l), Grace (Kotata) Swahaw, Jennie Lane, Michel Martineau, and Jennie Michel.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., bb015025

-

![]()

Tsin-is-tum (Jennie Michel), c.1911.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., 4354, photo file 561

-

![]()

Tsin-is-tum (Jennie Michel), c.1911.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., 4354, photo file 561

-

![]()

Michel Martineau.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., acc724, photo file 724

-

![]()

Michel Martineau.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., acc724, photo file 724

-

![]()

Necanicum River, Seaside, 1892.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., photo file 951G

-

![]()

Necanicum River, Seaside, 1892.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., photo file 951G

-

![]()

Necanicum River, Seaside, 1892.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., photo file 951G

-

![]()

Necanicum River, Seaside, 1892.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., photo file 951G

-

![]()

Non-Natives settled along Necanicum Creek, pushing out residents of Indian Place, still visible in the forested background of this photo, 1899.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., orhi79686

-

![]()

Non-Natives settled along Necanicum Creek, pushing out residents of Indian Place, still visible in the forested background of this photo, 1899.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., orhi79686

Related Entries

-

![Fort Stevens]()

Fort Stevens

One of the three major forts designed to protect the mouth of the Colum…

-

![Hobsonville Indian Community]()

Hobsonville Indian Community

The Hobsonville Indian Community was a Native settlement on Tillamook B…

-

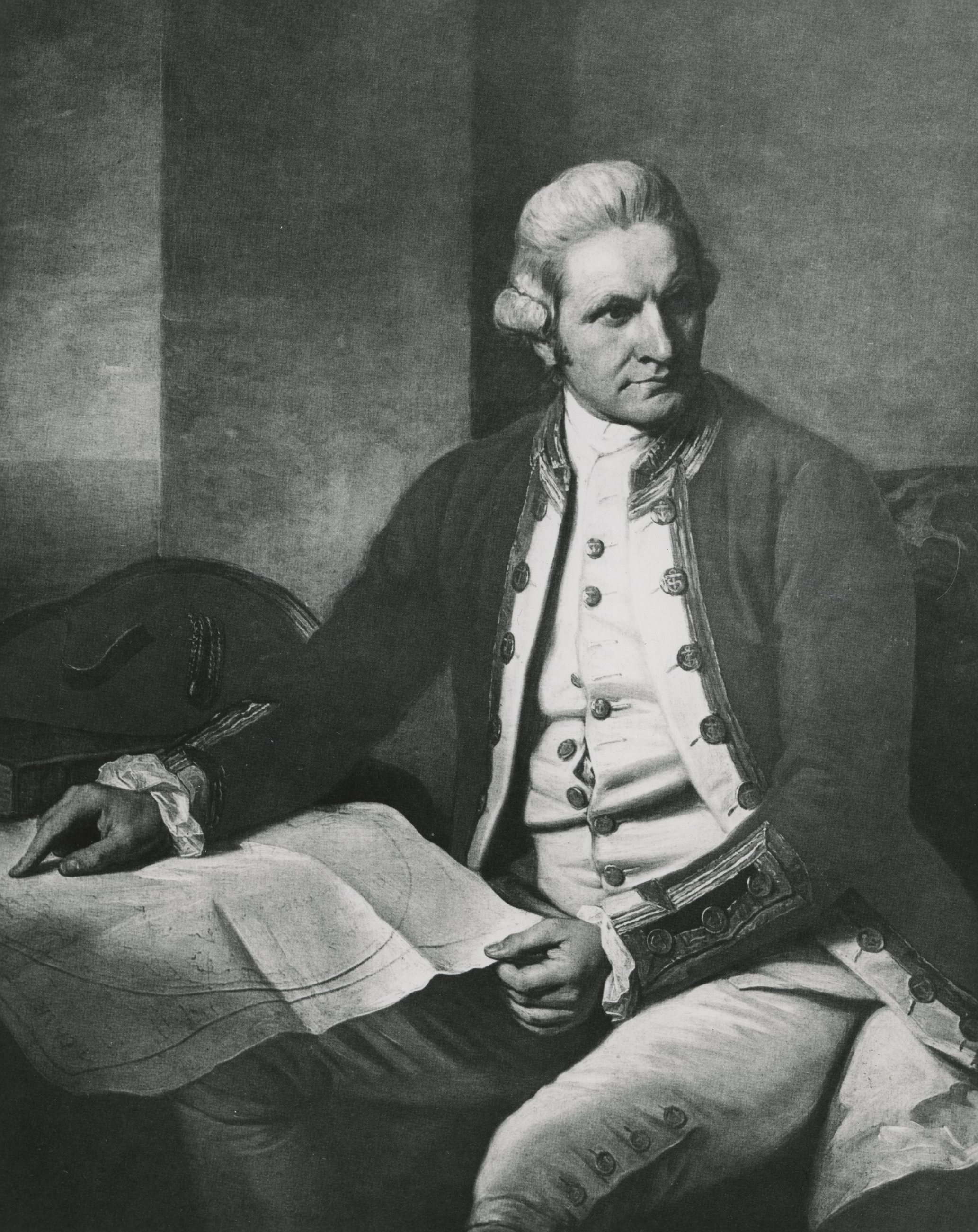

![James Cook (1728-1779)]()

James Cook (1728-1779)

In the lower right-hand corner of his magnificent Chart of the NW Coast…

-

![Point Adams]()

Point Adams

Located at the mouth of the Columbia River and marking the extreme nort…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Boas, Franz. "Chinook Texts." Bulletin of the U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology 20 (1894). U.S. Government Printing Office.

Deur, Douglas. Community, Place, and Persistence. Report to Oregon Heritage Commission, Salem OR, 2005.

_____. "The Making of Seaside’s 'Indian Place': Enduring and Contested Native Spaces on Oregon’s North Coast." Oregon Historical Quarterly 117.4 (Winter 2016): 536-73.

Ellis, David V. “Cultural Geography of the Lower Columbia.” In Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia, edited by K. Ames, R. Boyd, and T. Johnson. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013.

McChesney, Charles. Rolls of Certain Indian Tribes in Oregon and Washington. Fairfield, Wash.: Ye Galleon Press, 1969.

Michel, Jennie. Personal account, in L.B. Cox, “Report of the Committee of the Oregon Historical Society which investigated and accepted identification of the sites of Fort Clatsop and the Salt Cairn,” in Proceedings of the Oregon Historical Society, Annual Reports, 1899–1905. Portland: Oregon Historical Society (1900), Appendix A: 17.