Near Laurelhurst Park in Portland, above the street signs at Southeast Thirty-First Street and Pine, is a two-sided topper featuring the smiling face of a young Ethiopian immigrant, Mulugeta Seraw, killed there in a confrontation with racist skinheads in the early hours of November 13, 1988. The topper, written in both English and Amharic, is one of seventeen in the immediate area installed through the efforts of the Portland Urban League, Southeast Uplift, the Office of Community and Civic Affairs, the Kerns Neighborhood Association, and the Portland Bureau of Transportation. Unveiled in a public ceremony on November 13, 2018, the zone of remembrance is a tribute to an otherwise inconspicuous person whose killing made him a symbol of the rise of the White supremacist movement in the United States, as well as the opposition to it. But it is important to remember that before he became a public symbol, he was a man.

Born on October 21, 1960, Mulugeta Seraw began his life in a farming hamlet in the Ethiopian highlands. He moved to Addis Ababa in the 1970s to attend high school, following in the footsteps of an uncle, Engedaw Berhanu, who had studied there before moving to the United States in 1973. Berhanu had planned to complete his undergraduate studies and return to Ethiopia, but with the overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974 and the subsequent civil war, he could not go home. Instead, he settled in Portland, where he obtained a master’s degree in social work from Portland State University.

Living in Addis Ababa during the Red Terror, Mulugeta Seraw dreamed of furthering his education in the United States. In November 1980, he arrived in Oregon and moved in with his uncle in an apartment in Beaverton. He began business and engineering classes at Portland Community College and worked at a succession of jobs. When Berhanu moved to California to begin his career, Seraw stayed on, a welcome member of Portland’s growing Ethiopian exile community.

In the fall of 1988, Seraw was working as an airport bus driver and sharing an apartment at 212 Southeast Thirty-first Street. Next to it, on Pine, was an apartment frequented by White supremacists associated with East Side White Pride. At about one in the morning on November 13, as Seraw was being dropped off after a party, three skinheads and their girlfriends piled into their car at the southwest corner of Southeast Pine and turned onto Southeast Thirty-first Avenue, where Mulugeta and his Ethiopian friends were talking in their car. Blocked, the skinheads began honking and shouting. When they realized that the people in the other car were Black, they shouted racist slurs. Undoubtedly trying to stop the assault, Seraw got out of the car and walked toward his apartment, gesturing to the others to settle down, but it did not stop. As the men flew out from both cars and began to fight, he turned back from his door and ran down the street to help his friends. Within minutes, his head was smashed by one of the skinheads wielding a bat. Soon he was dead. The three skinheads later pleaded guilty, one to murder and two to manslaughter, and went to prison.

While the life of the man was over, the life of the symbol was just beginning. With the headline “SKINHEADS BLAMED IN MAN’S DEATH” in the next day’s Oregonian, the vulnerability of the state’s Black population was brutally exposed. In spite of the unbroken history of racism in Oregon—from the exclusion of Black people by the 1859 State Constitution to the open presence of neo-Nazi skinheads in the streets during the 1980s—its existence had been unacknowledged. “Racism is un-Oregonian” declared a political leader at an antiracism rally after Seraw’s death. As the killing remained the center of civic attention week after week, such denials of reality became increasingly difficult to sustain.

Drawing on the groundbreaking research of Portland State University professor Darrell Milner into the racist convictions that permeated the state’s origin and shaped its institutions, grassroots organizations such as the Coalition for Human Dignity (formed after Seraw’s death) carried the facts about Oregon’s racial history into Portland and other communities. After 1990, Seraw’s killing took on even broader significance, when a civil suit brought by the Southern Poverty Law Center in a Portland court successfully linked Portland’s East Side White Pride to California White Aryan Resistance leader Tom Metzger, bankrupting Metzger and giving the case a lasting place not only in the history of White supremacy in Oregon but in the history of the rise of the neo-Nazi movement in the United States and worldwide. By the time of the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020, almost every local news story began with a reference to Oregon’s constitutional exclusion clause.

With the passage of time, the life and death of Mulugeta Seraw have come to have an increasingly important role in the struggle against racism in Oregon. The date of his death is marked with public commemorations staged by organizations that include the Western States Center, the Urban League, the Oregon Jewish Museum and Center for Holocaust Education, and Fear No Music, a chamber orchestra that premiered a composition and film titled Nightwalk on the thirty-first anniversary of the fatal beating in 2019.

Mulugeta Seraw was a modest man from a troubled country seeking to finish his education in the United States, and he would doubtless be surprised by his renown. He was buried beneath a simple stone in Portland’s Riverview Cemetery, surrounded by the Portlanders of his adopted home.

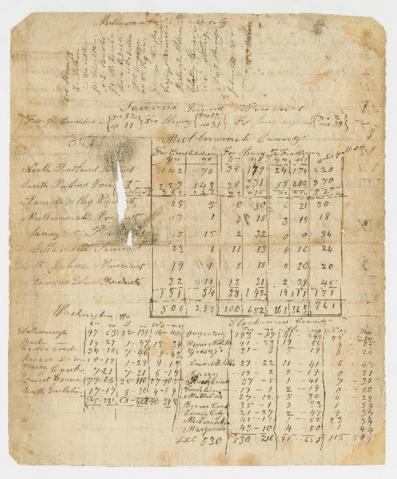

-

![]()

Mulugeta Seraw.

-

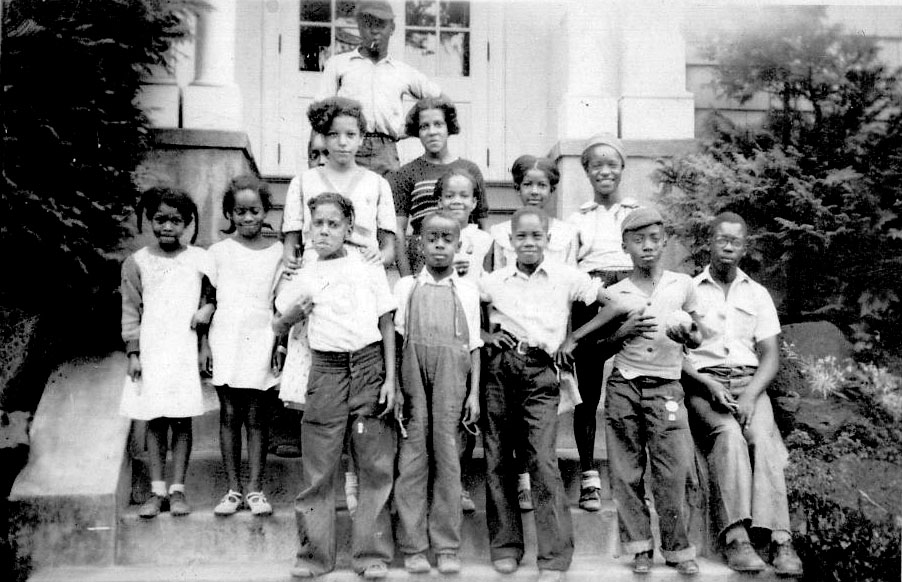

![]()

Anti-racism protesters gather in support of the conviction of Seraw's murderers, Pioneer Square, Portland, 1989.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Skanner Coll., bb001389

-

![Elden Rosenthal shows Berhanu a photograph of Mulugeta Seraw as Berhanu wipes tears from his eye.]()

Engedaw Berhanu, Seraw's uncle, testifies at the civil trial against the White supremacist Tom Metzger, 1990.

Elden Rosenthal shows Berhanu a photograph of Mulugeta Seraw as Berhanu wipes tears from his eye. Courtesy Portland Oregonian

-

![]()

Ancer Haggerty.

Courtesy U.S. District Court of Oregon Historical Society

Related Entries

-

![Ancer L. Haggerty (1944–)]()

Ancer L. Haggerty (1944–)

Ancer L. Haggerty was the first African American to become a partner in…

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![Elden Rosenthal (1947–)]()

Elden Rosenthal (1947–)

A respected and successful trial lawyer, Elden Rosenthal practiced law …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Langer, Elinor. A Hundred Little Hitlers: The Death of a Black Man, The Trial of a White Racist, and the Rise of the Neo-Nazi Movement in American. New York: Picador, 2003.

Langer, Elinor. “The American Neo-Nazi Movement Today.” Special Issue, The Nation (July 16/23 1990).