Louis Southworth came to Oregon in 1853, a time that was less than hospitable to African Americans. Most people who traveled the Oregon Trail by wagon were from the nation’s midwestern and border states, and many hoped to avoid the conflicts caused by slavery. Slavery was not legal in Oregon, but African Americans had been prohibited from settling in Oregon since the days of the provisional government. The Oregon State Constitution, passed in 1859, contained an exclusion clause that made it illegal for African Americans to live in Oregon (the clause was not repealed until 1926, and the population of African Americans in Oregon did not surpass one percent until 1960). Those prejudices and restrictions did not stop Southworth from making a good life in the state.

Southworth was born into slavery in Tennessee on July 4, 1829, and was twenty-four years old when his owner, James Southworth, brought him to Oregon. Southworth considered Louis to be his property in Oregon, and he and his brother William Southworth signed a petition to the Oregon territorial government to protect slave property. Before long, James Southworth, along with his family and Louis Southworth, left Oregon for California to try his hand at gold mining. Louis Southworth soon found that he could make more money playing his violin for dance schools, and by 1858, he had raised $1,000 (equivalent to $23,000 in 2009), enough money to purchase his freedom.

Louis Southworth would first live on an Oregon Donation Land Claim that Benjamin Richardson allowed him to settle in 1853, a claim near Monroe that Richardson’s son had abandoned. Richardson and his family may have known the Southworths in Missouri; they had lived in the same town (Boone) and had immigrated to Oregon five years before. The law did not allow Louis Southworth to apply for his own Oregon Donation Land Claim, since the privilege was only extended to whites and "half-breed Indians."

In 1870, Louis Southworth lived in Buena Vista, where he ran a livery stable and worked as a blacksmith on the 100-foot-wide main street of the town of 183 residents. In 1873, he married Mary Cooper, whose adopted son, Alvin McCleary, Southworth would help raise.

The Homestead Act of 1862 did not restrict by race (although it did restrict by "citizenship," which excluded many non-whites), and in 1879, Southworth and his family took up a homestead in the Alsea Valley. He cleared ten to twelve acres per year over a six-year period, using animal power and a wooden plow, hunted with a homemade rifle, and fished to supply food for the family. He also built a sawmill and ferried people up the Alsea River. Southworth was an active member of the community. He donated land for a school, taught his horse tricks for a show at the Oregon State Fair, and played his fiddle for dances in Waldport.

When Southworth was told he could not attend the local Baptist church if he continued to play his fiddle, he said: “Was brought up a Baptist. But the brethren would not stand my fiddle, which was about all of the company I had much of the time. So I told them to keep me in the church with my fiddle if they could, but to turn me out if they must, for I could not think of parting with the fiddle. I reckon my name isn’t written in their books here anymore; but I somehow hope it’s written in the big book up yonder, where they aren’t so particular about fiddles.”

Louis Southworth died on June 28, 1917, at almost eighty-eight years old. In 1999, his name resurfaced when Jessica Dole, a landscape architect for the Siuslaw National Forest, challenged the names of the road and creek that ran through Southworth’s old homestead—Darkey Road and Darkey Creek. Some argued that the names should not be changed in order to preserve the region’s history. The Oregon Geographic Names Society ultimately changed the name of the creek, but not the road. Somewhat hidden in the trees is the sign Darkey Road, but clearly seen on the Alsea Highway is the sign for Southworth Creek.

The town of Waldport commissioned sculptor Pete Helzer to create a bronze statue in honor of Louis Southworth and his contributions to the community. The statue was officially dedicated at the Alsea Bay Bridge Visitor Center and Museum in Waldport on November 19, 2022, and will be placed in Louis Southworth Park in 2024.

-

![Louis Southworth.]()

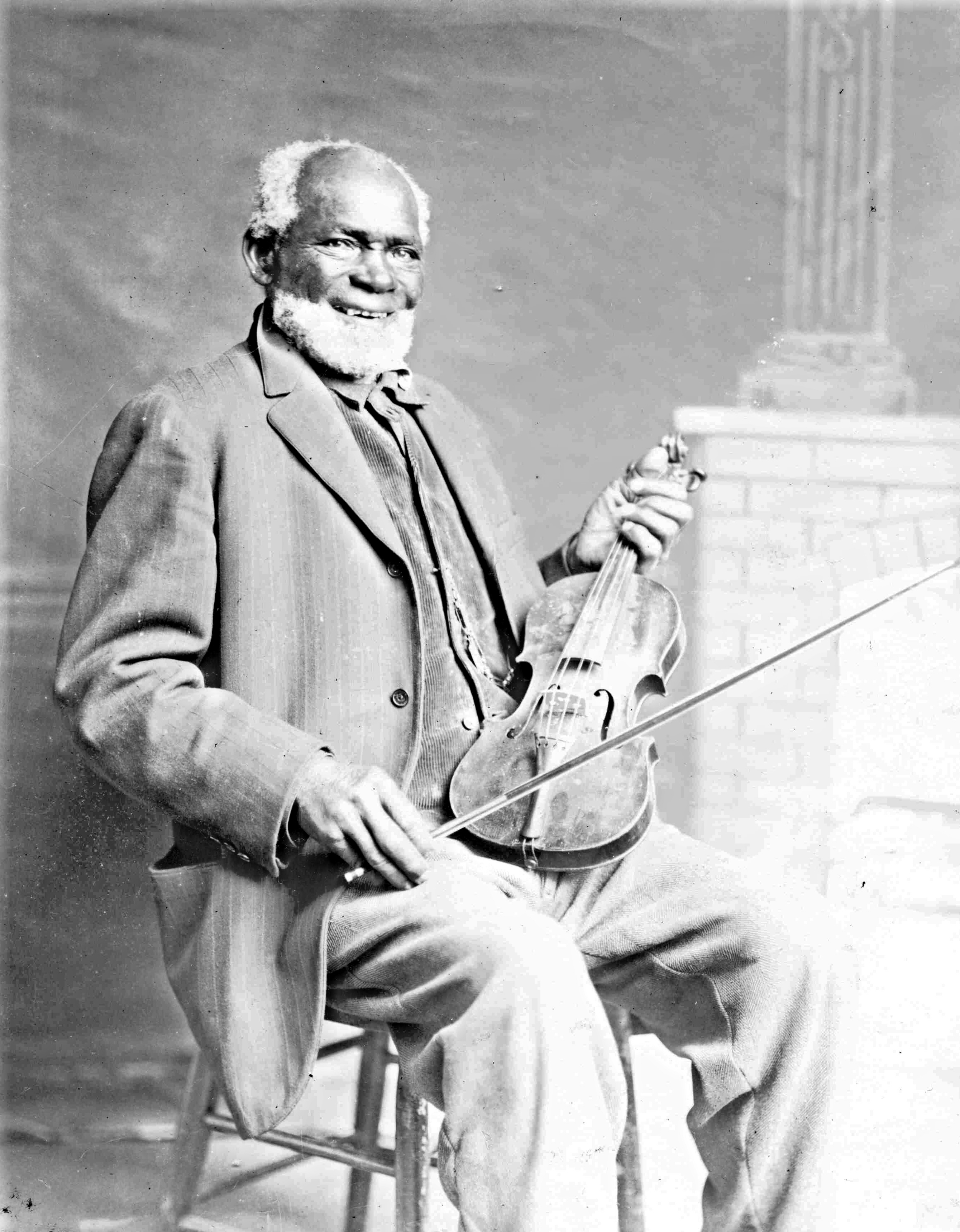

Southworth, Louis, with violin.

Louis Southworth. Benton County Hist. Soc. Museum, 1991-041.0054N

-

![Louis Southworth.]()

Southworth, Louis, at fireplace.

Louis Southworth. Benton County Hist. Soc. Museum, 1991-041.0054N

Related Entries

-

![Abner Hunt "A. H." Francis (c. 1812–1872) and Isaac "I. B." Francis (1798-1856)]()

Abner Hunt "A. H." Francis (c. 1812–1872) and Isaac "I. B." Francis (1798-1856)

A. H. Francis, a free Black, was a merchant and activist who in 1851 op…

-

![Ben Johnson (1834–1901)]()

Ben Johnson (1834–1901)

Ben Johnson was a Black pioneer of Jackson County who came to Oregon as…

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![Black People in Oregon]()

Black People in Oregon

Periodically, newspaper or magazine articles appear proclaiming amazeme…

-

![George Bush (c. 1790-1863)]()

George Bush (c. 1790-1863)

George Bush, sometimes named as George Washington Bush in the historica…

-

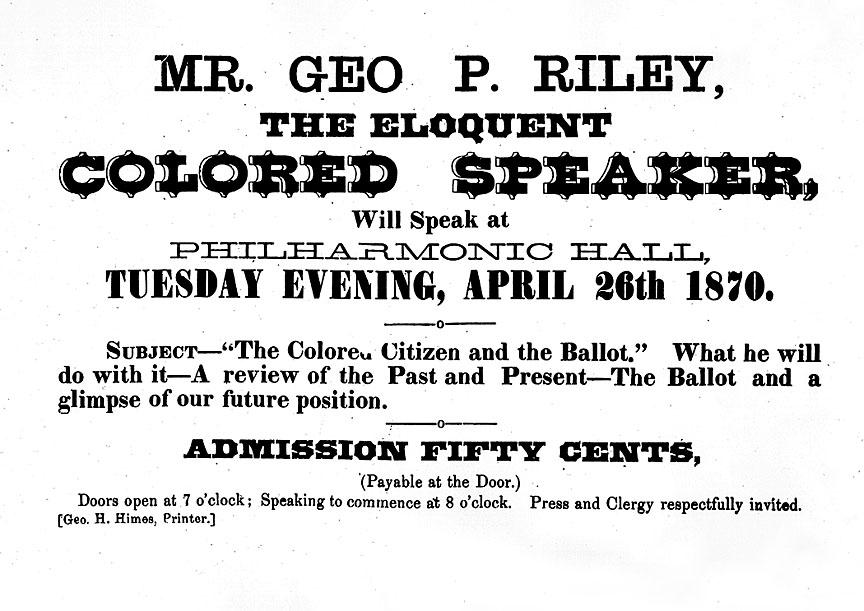

![George Putnam Riley (1833–1905)]()

George Putnam Riley (1833–1905)

Identified by the Oregonian as the “Fred[erick] Douglass of Oregon,” Ge…

-

![James William Beatty (1830–1914)]()

James William Beatty (1830–1914)

From his arrival in Oregon in about 1864 until his death in 1914, James…

-

![John A. Brown (1830?–1903)]()

John A. Brown (1830?–1903)

John Brown Canyon heads on Agency Plains, seven miles north of Madras, …

-

![Oregon Trail]()

Oregon Trail

Introduction In popular culture, the Oregon Trail is perhaps the most …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Baldwin, Peggy. "A Legacy Beyond the Generations," 2006.

McLagan, Elizabeth. A Peculiar Paradise: a History of Blacks in Oregon, 1788 – 1940. Portland, Ore.: The Georgian Press, 1980.