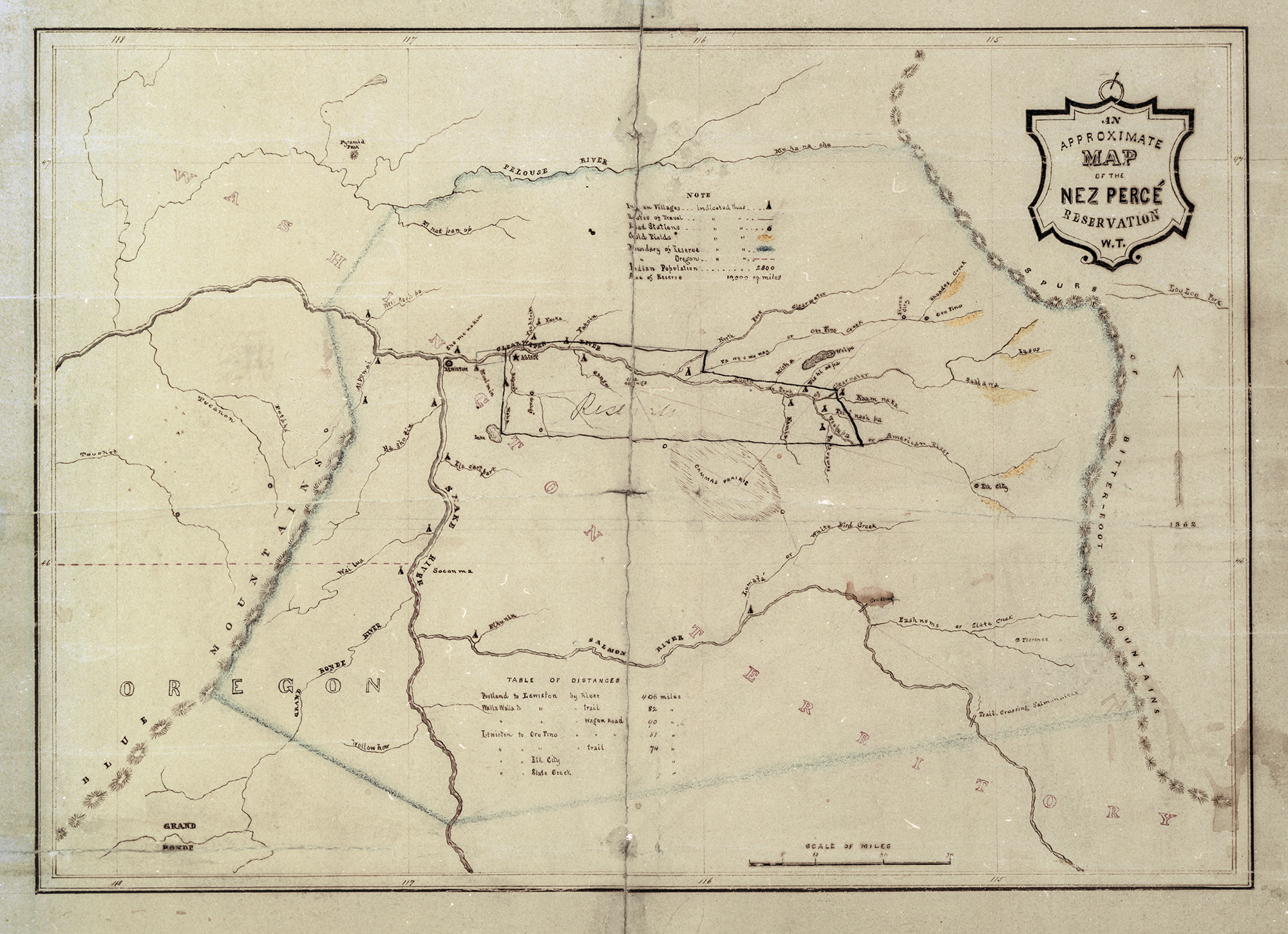

When Oregon achieved statehood in 1859, its southeastern quadrant remained largely unexplored by either European adventurers or white settlers. That began to change during the American Civil War, when most Union Army soldiers remaining in Oregon—most of them white male residents—replaced regulars who were reassigned to fight the Confederacy in battle theaters in the East. At the same time, some Northern Paiute bands in eastern Oregon and parts of Nevada and the Idaho territories attacked remote outposts of white settlers and travelers. Captain Franklin B. Sprague commanded one company of infantry during the later stages of this guerrilla war. From 1864 to 1867, he also explored portions of what are now Klamath, Lake, Harney, and Malheur Counties, beginning with a reconnaissance under Colonel C. S. Drew that determined how to move troops from Fort Klamath to the area around Steens Mountain.

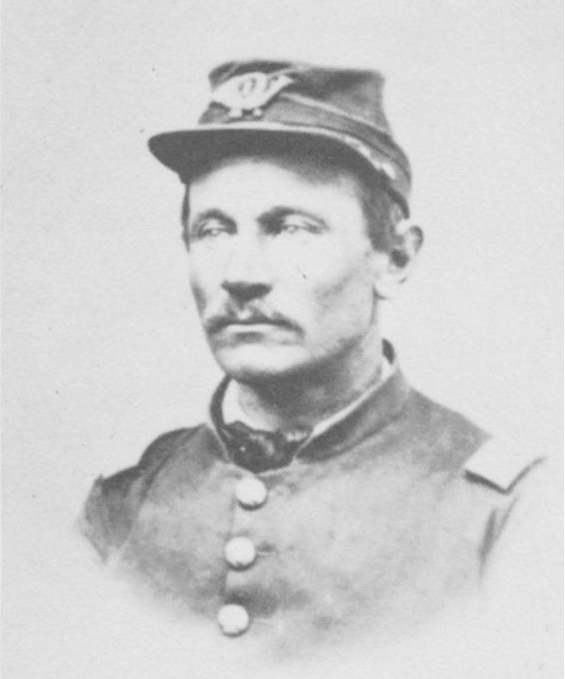

Franklin Sprague was born in Delaware, Ohio, on July 16, 1825. He attended a private school and was a student at Ohio Wesleyan University during its first two years of operation. He also trained to be a miller and specialized for a time in the manufacture of fanning mills for grain. In 1850, he emigrated to Oregon with his wife and three children, initially settling at Perkinsville (present-day Grants Pass) and later at Gassburg (present-day Phoenix), where he ran a flour mill until he entered active military service.

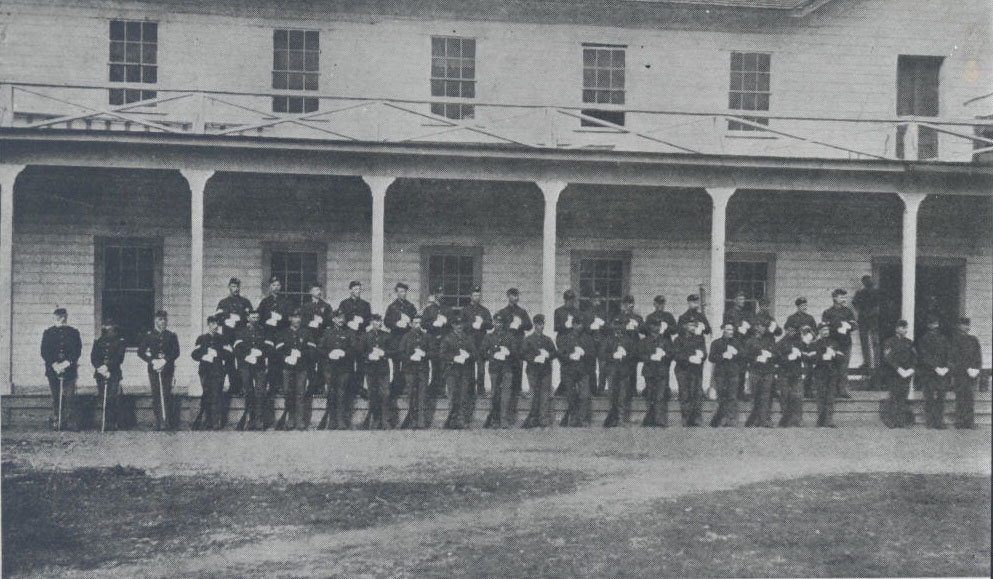

Beginning in 1861, a regiment called the First Oregon Volunteer Cavalry replaced U.S. Army regulars. In the fall of 1864, with that first round of volunteer enlistments due to run out, President Abraham Lincoln issued a call for volunteers to fill the void and include infantry. This occurred as regimental commanders embraced a new strategy in the Northern Paiute conflict in an effort to hasten the end of hostilities. Instead of conducting operations only in the summer and fall from bases in western Oregon, the army decided to establish a ring of camps in the Northern Paiute homeland that would be occupied all year.

In late 1864, Franklin Sprague was a U.S. Army recruiter charged with raising a company of volunteer infantry from Jackson, Josephine, Coos, and Curry Counties. He was commissioned as a captain, and in the early summer of 1865 he led eighty men from Camp Baker in the Rogue Valley to the recently established Fort Klamath. Soon after their arrival, Sprague helped locate a new supply road across the Cascades, linking Fort Klamath with the Rogue River, where another road led to Jacksonville.

Opening the new road led Sprague and a small group of men to Crater Lake, where in August 1865 they made the first recorded visit to the shoreline. While there, Sprague correctly ascertained the lake’s volcanic origin. He publicized the group’s discovery in a Jacksonville newspaper. The news traveled well beyond southern Oregon, and tourists began visiting the lake almost immediately. The territory around Crater Lake was the homeland of Klamath, Southern Molalla, Upland Takelma, Umpqua, and other Indigenous peoples who used the rim area for ritual purposes and moved over the lower slopes of what was later called Mount Mazama for hunting and gathering.

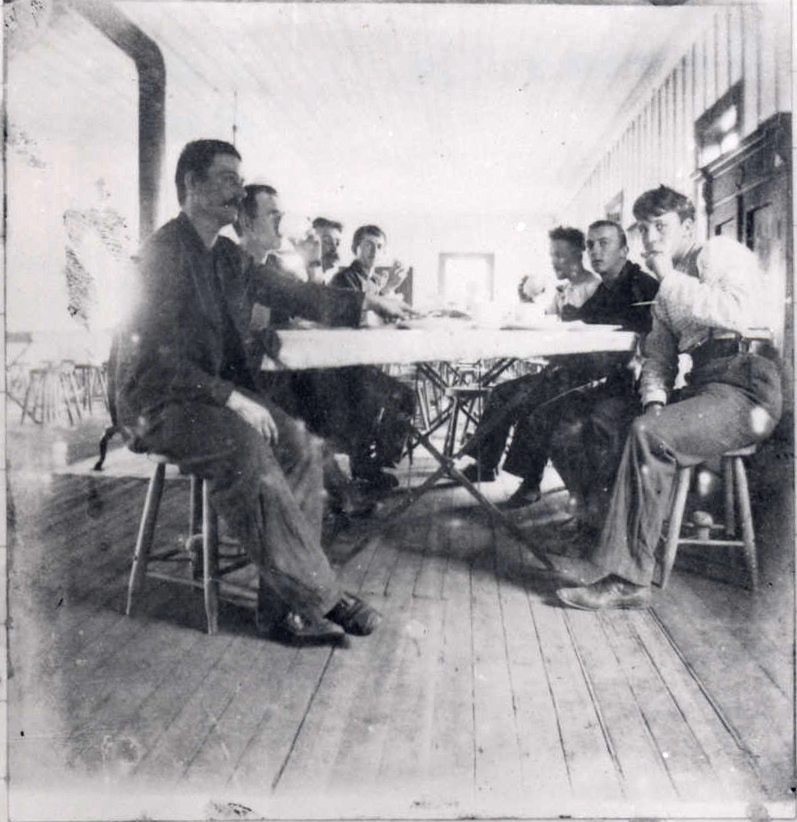

Shortly after Sprague’s visit to Crater Lake, he received an order directing him to establish Camp Alvord near Steens Mountain, some 250 miles from Fort Klamath. As part of the operation against Northern Paiutes bands, Sprague became known as a quick-thinking leader of the volunteers, a man who deftly sidestepped an ambush by more than a hundred warriors at the base of Hart Mountain and suffered no casualties. After months in the field, he took command of Fort Klamath in the summer of 1866, an assignment that lasted for almost a year while U.S. Army regulars gradually returned to Oregon. His infantry company gained the distinction of being the last group of volunteers to muster out of service, at Jacksonville in July 1867.

Once Sprague returned to civilian life, he remained at Fort Klamath, where he helped run a store that served army regulars and got occasional work as a scout or interpreter. In July 1868, he participated as an interpreter in an army expedition from the fort, but by the end of August the conflict with Northern Paiute bands had ended. Afterward, he made a trip as a guide to Crater Lake, which he called Lake Majesty, and wrote one last newspaper article about the lake.

In the fall of 1868, Sprague and his family returned to Delaware, Ohio, where he resumed his grain-milling business and served two terms as a probate judge. He died on February 7, 1895. The Sprague River, which drains portions of Klamath and Lake Counties, is named for him.

-

![]()

Franklin B. Sprague.

Courtesy Klamath Historical Society

-

![Boating on Crater Lake.]()

Crater Lake, Gifford photo, OrHi neg,. GI10133, OHQ 1-02.

Boating on Crater Lake. Photo by Benjamin Gifford, courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., GI10133

Related Entries

-

![1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry]()

1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry

During the 1860s, the major military-Indian conflicts of the Pacific No…

-

![2nd Oregon Volunteer Infantry]()

2nd Oregon Volunteer Infantry

Relations between the United States and Spain were already strained ove…

-

![Crater Lake National Park]()

Crater Lake National Park

Crater Lake National Park, which the U.S. Congress set aside in 1902, i…

-

![Fort Klamath]()

Fort Klamath

During the Civil War era, tens of thousands of people immigrated to the…

-

![Grants Pass]()

Grants Pass

Located on the Rogue River about thirty miles northwest of Medford, Gra…

-

![Mount Mazama]()

Mount Mazama

Mount Mazama is located in the southern part of the Cascade Range, abou…

-

![Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon]()

Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon

After American immigrants arrived in the Oregon Territory in the 1840s,…

-

![Steens Mountain]()

Steens Mountain

Rising to an elevation of 9,733 feet, Steens Mountain is the highest po…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Ogle, Jim, and Clayton Chocktoot. Fort Rock and Paisley Cave Descendants: The Chocktoot Bands of the Paiute Snake Tribes. Lakeview, Ore.: Lake County Historical Society, 2018.

LaLande, Jeff. “'Dixie' of the Pacific Northwest: Southern Oregon’s Civil War.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 100.1 (Spring 1999): 32-81.

Mark, Stephen R. “Captain Sprague’s Big Adventure.” Journal of the Shaw Historical Library 26 (2012): 3-15.

Movius, James Gilbert. “White-Paiute Conflicts, 1825-1868.” Journal of the Shaw Historical Library 6 (1992): 33-93.