Rising to an elevation of 9,733 feet, Steens Mountain is the highest point in southeastern Oregon. It looms like a massive basalt island, with its summit over 5,000 feet above the Alvord Desert to the east. Because of its variety of elevation zones and its topographical diversity—the result of heavy glacial carving during the Ice Age—Steens Mountain has many wildlife habitats and vegetation communities, from sagebrush steppe and juniper woodland at the lower elevations, to groves of quaking aspen at mid-elevations and mountain mahogany near the summit, to hardy subalpine perennials at the rocky crest.

Steens Mountain also has a rich human history, dating from hunter-gatherers in the late Ice Age to the livestock ranchers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In recent decades, it has been a magnet for recreationists, including hikers, hunters, and cross-country skiers. Steens Mountain is an iconic part of the Oregon’s High Desert landscape.

A north-south escarpment over forty miles long, Steens Mountain is “the largest fault-block mountain in the northern Great Basin.” During the late Miocene Epoch, between fifteen and eight million years ago, successive flows of basalt accumulated in layer-cake fashion to create the Steens Mountain Basalts. Southeastern Oregon’s basalt flows underwent severe geological stress during the Pliocene Epoch, from seven to four million years ago, expanding and compressing along north-to-south fault zones to create a basin-and-range terrain. Some areas of basalt sank, creating the High Desert’s lower-lying basins, including the Catlow Valley and the Alvord Desert.

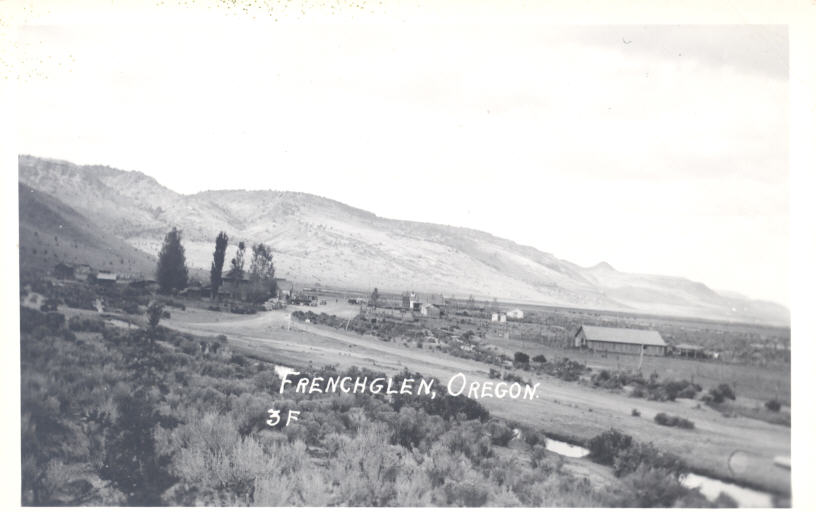

The east face of Steens Mountain is extremely steep, while its west slope is a gentle, gradual incline, making it possible to build a seventeen-mile-long road to the summit from the hamlet of Frenchglen. During the cooler, moister climate of the Pleistocene Epoch, between four million and ten thousand years ago, glaciers carved out the mountain’s dramatic canyons, including Kiger Gorge, Little Blitzen Gorge, and Big Indian Gorge.

The people who were living in the region when the first Euroamericans arrived in the early nineteenth century were the Northern Paiute. They spoke a Shoshonean language that belonged to the much larger Uto-Aztecan language family. Their ancestors likely migrated to Oregon's High Desert a few thousand years ago from the southern Great Basin, near California's Owens Valley. The human history of the Steens Mountain area before the occupation of the Paiute is unknown.

On the sagebrush flats of the former lakebeds, the Paiutes held communal jackrabbit drives, harvested plants, and hunted bighorn sheep, pronghorn antelope, and mule deer. The small Tsisi-adi band of Paiute inhabited the cold, eastern foot of the mountain and nearby Alvord Basin; the more numerous Wadatika Paiute people lived near Malheur Lake and ranged along the northwestern foot of Steens Mountain. Descendants of the Northern Paiute who once used the resources of Steens Mountain include members of the Burns Paiute and the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs.

In June 1831, Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader John Work recorded that the mountain was “covered with snow,” and because of this early description it appeared on some early maps as the Snow Mountains. The U.S. Army named the mountain in 1860 during the small-scale but brutal conflict known as the Snake Wars, when Major Enoch Steen skirmished with Northern Paiutes there during a patrol. Initially, 1870s maps misspelled it as Steins; although the name likely was intended to include a possessive apostrophe, mapmakers did not include it.

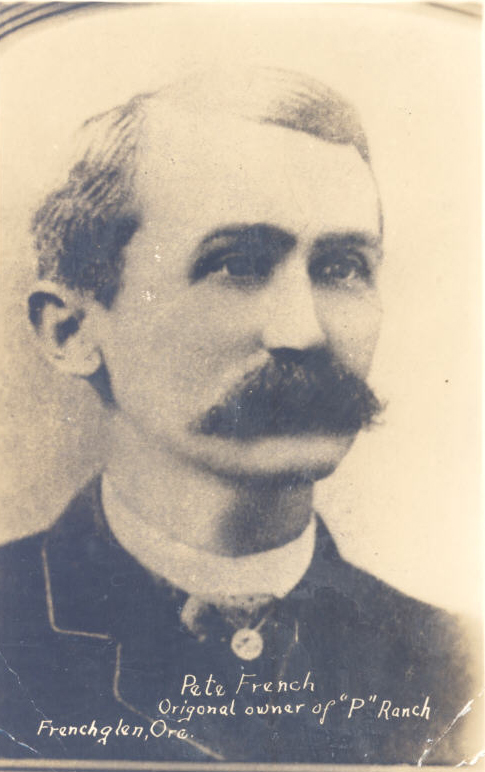

By the early 1870s, the first cattlemen had arrived in the area. Pete French’s P Ranch spread at the western foot of Steens Mountain along the Donner und Blitzen River, and John Devine established the vast Whitehorse Ranch off to the east in the Trout Creek, Alvord Basin area. Steens Mountain provided seasonal grazing for cattle, horses, and sheep. The pressure of livestock grazing, especially during the late nineteenth century, led to the disappearance of much of the area's rich bunchgrass, which was replaced by sagebrush and other less desirable species. The seasonal presence of buckaroos and sheepmen on Steens Mountain in the early 1900s, along with the commerce of a few prostitutes, resulted in the name Whorehouse Meadows, east of Fish Lake.

Cattle and sheep graze parts of Steens Mountain today, and a number of working ranches operate along the base of the eastern escarpment. Herds of wild horses, including the Kiger herd on the northwest slope of the mountain, are remnants of the ranching era. Horse numbers continue to proliferate, sometimes dominating crucial water holes and consuming substantial amounts of the area's sparse range grasses in competition with cattle and wildlife.

Steens Mountain drew few visitors until after World War II, except local residents and adventuresome hunters from the west side of the Cascades. The Bureau of Land Management, which administers most of the mountain’s acreage, punched a road from Frenchglen to the summit for livestock management purposes, as well as for hunting, camping, and other recreational uses. The road system, described by some as Oregon's "highest road," also accesses a major electronic communications facility at the summit. A south road to the summit provides additional access, linking with the older north road to create a popular loop drive.

In 1967, E.R. Jackman and John Scharff published a coffee-table book, Steens Mountain, in Oregon’s High Desert Country, which reproduced evocative photographs by Charles Conkling. In his review, Eugene Register-Guard writer W.L. Wassman wrote: “while you are up there [at the summit] and looking at the five states you may also see all the way to the state of your soul." Steens Mountain had a new audience, and interest in visiting the remote desert landscape grew. By the 1990s, the historic Frenchglen Hotel had become a base of operations not only for hunters but also for sightseers, photographers, hikers, birders, cross-country runners, and mountain bikers.

In October 2000, Congress established the Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protective Area, which includes federal, state, and private lands. Now at 496,143 acres in size—428,502 acres of federal land, 66,502 acres of private land, and 1,069 acres of state land—the Steens Mountain CMPA was a compromise forged by Secretary of Interior Bruce Babbitt and others in response to local opposition to a proposed Steens Mountain National Monument. The CMPA contains a number of land allocations, including areas opened or closed to grazing, wild and scenic river status for Kiger Creek and other glacial-canyon streams, over 170,000 acres of wilderness, and the withdrawal of nearly one million acres from mining and geothermal exploitation. Questions remain on the CMPA over whether it is the government's or private landowners' responsibility to pay for fencing, and a recent proposal for wind-power turbines was dropped when it met stiff opposition from environmentalists and some ranchers. Recreational use at Steens Mountain continues to give an important economic boost to Harney County.

-

![]()

Eastern face of Steens Mountain, near Alvord Valley, 1932.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 006894

-

![]()

Snow-covered Steens.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi52458

-

View from top of the Steens, Alvord Desert on the right.

Courtesy A.E. Platt

-

Top of Steens, with view of Alvord Desert.

Courtesy A.E. Platt

-

Kiger Gorge.

Courtesy A.E. Platt

Related Entries

-

![Alvord Desert]()

Alvord Desert

The Alvord Desert, east of the Pueblo Mountains and Steens Mountain and…

-

Buckaroos

For over a century-and-a-half, buckaroos have done the work on the ranc…

-

![Donner und Blitzen River]()

Donner und Blitzen River

From its headwaters on Steens Mountain, the Donner und Blitzen River wi…

-

![Frenchglen Hotel]()

Frenchglen Hotel

Frenchglen is a small desert community sixty miles south of Burns whose…

-

![High Desert]()

High Desert

Oregon’s High Desert is a place apart, an inescapable reality of physic…

-

![John William "Pete" French (1849-1897)]()

John William "Pete" French (1849-1897)

Peter (or Pete) French was a stockman of near-legendary status who ran …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Grayson, Donald K. The Great Basin: A Natural Prehistory. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

Jackman, E.R. and John Scharff. Steens Mountain in Oregon's High Desert Country. Caldwell, ID.: Caxton Printers, 1967.

LaLande, Jeff. "High-Desert History: Southeastern Oregon." Oregon History Project, Oregon Historical Society, 2005. http://oregonhistoryproject.org/narratives/high-desert-history-southeastern-oregon/

St. John, Alan D. Oregon’s Dry Side: Exploring East of the Cascade Crest. Portland, Ore.: Timber Press, 2007.