Benjamin Stark was a merchant, land speculator, and politician active in Oregon from 1845 to 1862. He played a central part in the early development of Portland and was deeply involved in the controversies that divided Oregon and national politics in the Civil War era. Stark was “dapper, shrewd and loquacious” but also “competitive and argumentative,” according to historian G. Thomas Edwards. Political opponents at the Oregon Statesman termed him “Blarney Stark.”

Born in New Orleans on June 26, 1820, Stark grew up in New London, Connecticut, and moved to New York at age fifteen to read law and work in mercantile houses. In 1845, the firm of A.G. and A.W. Benson employed him to sail on their ship Toulon, accompanying a shipment of goods consigned to Francis Pettygrove in the new town of Portland. While there, Stark fortuitously purchased Asa Lovejoy’s undivided half interest in the townsite for $390. Soon thereafter, he left on the Toulon for Honolulu, China, and New York, where he learned of the California gold strike and quickly arranged for a shipment of goods to San Francisco. When his New York partner went broke, Stark’s Portland property was his major asset, and he relocated to the growing city in 1850.

Unclear real estate partnerships are recipes for trouble, and Stark found that Daniel Lownsdale, William Chapman, and Stephen Coffin, who shared the other half interest in the property after 1849, had been selling lots in Stark’s absence. By an agreement hammered out in San Francisco by Stark and Lownsdale, the three partners took the bulk of the townsite while Stark took ownership of a wedge of roughly 48 acres bounded by the Willamette River and what are now SW Harvey Milk (once Stark) and Ankeny Streets. This plot included much of the early settled area and thus promised quick returns from land sales and rents, whereas Lownsdale, Chapman, and Coffin were in the best position to benefit as the city grew. Stark soon complained to his sometime business associate John Couch that he had the bad side of the deal.

Stark was an important figure among Portland’s mercantile community during the 1850s. He married Elizabeth Molthorp in 1852 and represented Washington County, which then included Portland, for one term (1852-1853) in the territorial legislature as a Whig. He preferred to support private rather than public institutions, helping to organize and lead a Masonic lodge and supporting Trinity Episcopal Church. He opposed taxation for public schools, but helped fund Trinity’s school.

As Oregon moved toward statehood at the end of the 1850s, Stark again entered politics. With the collapse of the Whig Party, he became a conservative Democrat who considered the Republicans sectional and fanatical. He secured election to the legislature in 1860, where he took an active role and was a firm supporter of slavery, believing that Congress should protect it throughout the nation. As national politics realigned, Oregonians in 1860 could choose among the Republicans; the Northern Democrats, who were Unionists and backed Stephen Douglas for president; and Southern-leaning Democrats, who backed John C. Breckinridge. Stark was firmly in the third camp and considered the outbreak of war in 1861 to be Northern aggression that denied Southern states their constitutional right to secede.

On October 21, 1861, Oregon Senator Edward Baker, a staunch Unionist who was a soldier as well as a statesman, died while leading his regiment at the Battle of Ball's Bluff. Frenzied jockeying for his replacement ensued. Governor John Whiteaker, a Southern sympathizer, surprised Matthew Deady, usually a shrewd observer, by appointing Stark to fill out Baker’s term, shifting the political balance of Oregon's men in Washington. Stark’s political enemies were livid. The Oregon Statesman called him a “secessionist of the rankest dye and the craziest professions…as far as words spoken can constitute treason; he is a traitor as infamous as any that disgraces northern soil.” Henry Corbett and other Oregon Republicans urged Republican senators to prevent Stark from taking office, calling him disloyal and potentially capable of betraying the nation.

Acrimonious hearings in Washington, D.C., delayed Stark’s formal seating by several weeks, with powerful figures such as Charles Sumner and Lyman Trumbull opposing him. His status was unresolved until June 1862, when the Senate voted 21-16 not to take up a recommendation for expulsion. Stark served as interim senator until September 12, 1862, when the legislature replaced him with Benjamin Harding. During his brief time in office, Stark voted for the legislation to create land grant universities and against the Homestead Act.

At the end of his undistinguished term in Congress, Stark moved to New London rather than return to Oregon. He remained active in politics, serving as a delegate to the 1864 Democratic convention for Oregon and the 1868 convention for Connecticut, as New London alderman, and in the Connecticut legislature. He practiced law and drew income from his Portland holdings.

His Portland property continued to create problems for Stark, and he could be overly pushy in business dealings. Lownsdale had agreed that the partners in the property would compensate him for the lots within Stark’s zone that had been sold before 1850, but Stark was sometimes slow to recognize the new owners. Addison Starr (Portland’s mayor in 1858-1859) and his brother sued over one such parcel and eventually earned Stark a stinging rebuke from the U.S. Supreme Court in 1876, in one of the many cases in which the postbellum court led by Stephen Field worked to clarify and support property and contract rights. When the heirs of Daniel Lownsdale contested city title to six central Park Blocks, Stark declined an opportunity to be a benefactor to his previous home. Rather than donating the land, as his former associate John Couch had done earlier with the North Park Blocks, he offered to sell for $138,000—the equivalent of several million dollars in 2018 and money the city did not have and did not pay.

Stark died on October 10, 1898, in New London.

Benjamin Stark was in the right place at the right time in 1845, and he benefitted from the growth of Portland, perhaps more than he contributed. His representation of Oregon in Congress was brief and ineffective, because his sympathy with slavery and secession put him on the outs with the majority of Oregonians and on the wrong side of the Civil War. Ironically, the street that once bore his name in Portland (now Harvey Milk on the west side) follows the baseline for the U.S. land survey in Oregon, one of the foundations for the state’s growth.

-

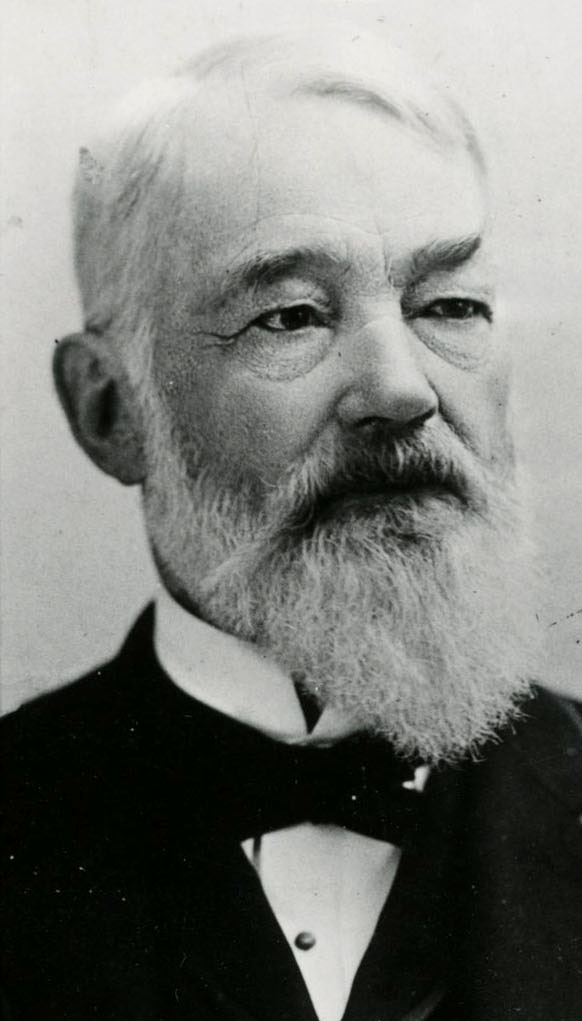

![Benjamin Stark]()

Benjamin Stark, c.1885.

Benjamin Stark Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, 014112

-

![]()

-

![]()

Front and Stark Streets in Portland, 1852.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi946

Related Entries

-

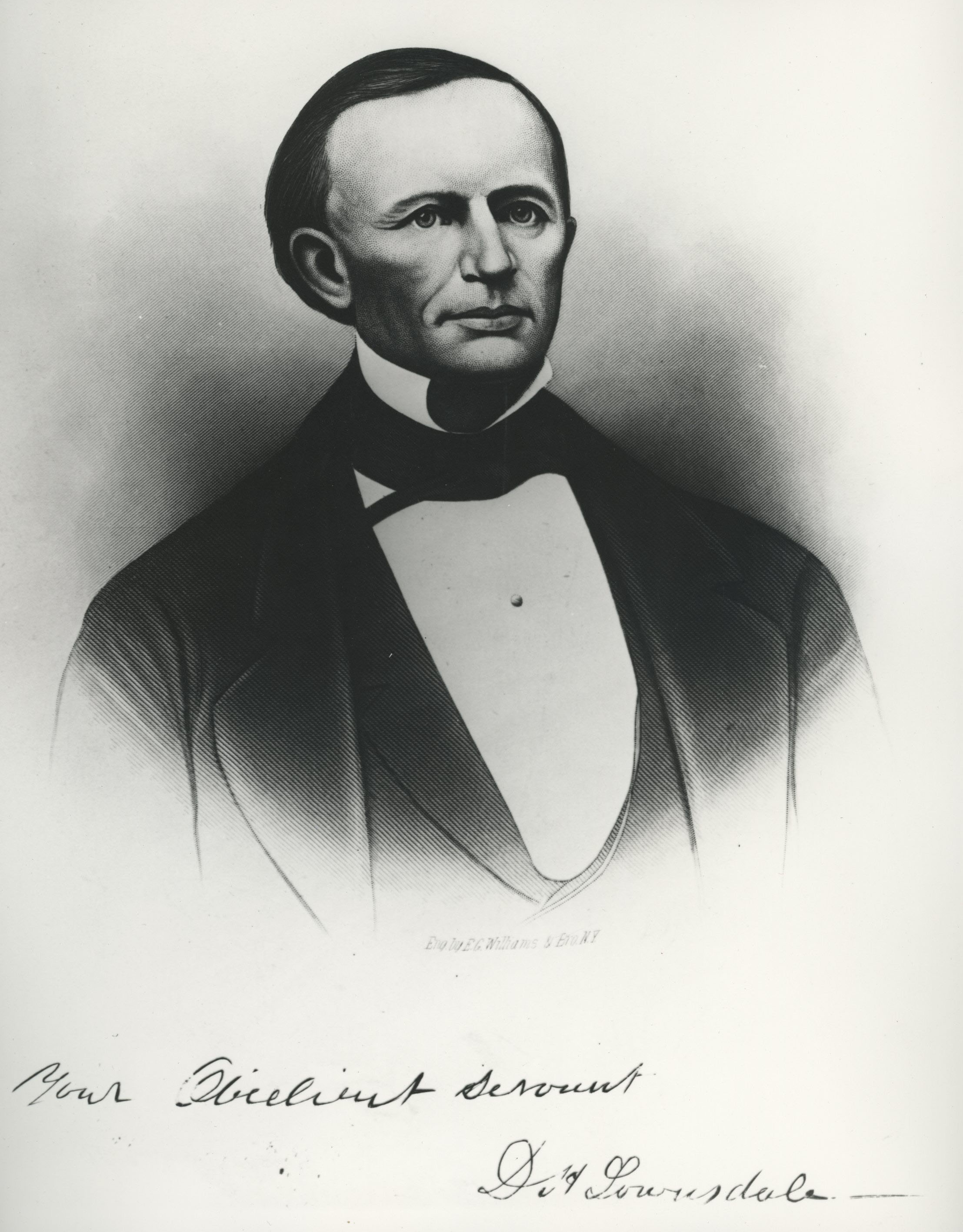

![Daniel Lownsdale (1803–1862)]()

Daniel Lownsdale (1803–1862)

Daniel H. Lownsdale was an early Portland townsite settler who served i…

-

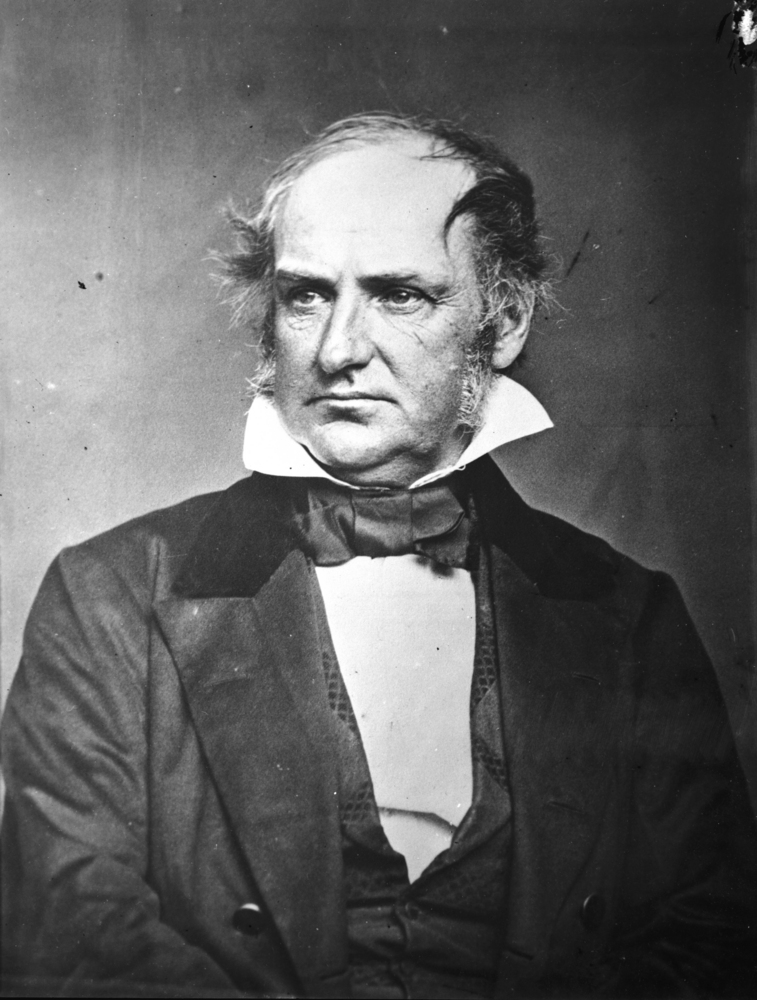

![Edward Baker (1811-1861)]()

Edward Baker (1811-1861)

Edward "Ned" D. Baker, who was born in London, England, on February 24,…

-

![Francis Pettygrove (1812-1887)]()

Francis Pettygrove (1812-1887)

Entrepreneur and Portland co-founder Francis W. Pettygrove was born in …

-

![Henry W. Corbett (1827-1903)]()

Henry W. Corbett (1827-1903)

In early 1851, Henry W. Corbett, an ambitious, twenty-four-year-old adv…

-

![Matthew Deady (1824-1893)]()

Matthew Deady (1824-1893)

Matthew Paul Deady was a lawyer, politician, and judge in the Oregon Te…

-

![Portland]()

Portland

Portland, with a 2020 population of 652,503 within its city limits and …

-

![Portland Park Blocks]()

Portland Park Blocks

While America's premier landscape architect, Frederick Law Olmsted, tra…

-

![Trinity Episcopal Cathedral]()

Trinity Episcopal Cathedral

The history of Trinity Episcopal Church, now the cathedral of the Dioce…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Davis, Rob. "The Oregonian's Racist Legacy." The Oregonian. October 24, 2022.

Lansing, Jewel. Portland: People, Politics and Power, 1851-2001. Covallis: Oregon State U. Press, 2005.

Joseph Gaston, Centennial History of Oregon, 1811-1912

McKinley Corning, Howard. Dictionary of Oregon History. Chicago, Ill: S.J. Clarke Pub., 1912.

Edwards, G. Thomas. “Benjamin Stark, the U.S. Senate, and 1862 Membership Issues, Part I.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 72.4 (December 1971): 315-338; and “Benjamin Stark, the U.S. Senate, and 1862 Membership Issues, Pt. II." Oregon Historical Quarterly 73.1 (March 1972): 31-59.