In May 1904, in State of Oregon v. Norman Williams, an Oregon jury made legal history by convicting a man of murder without having a body as evidence. In a legal system based on precedent, the case continues to be cited in murder cases today.

Daniel Norman Williams was born in Sombra, Ontario, on January 17, 1857. He served three years in a Nebraska penitentiary for assaulting and nearly killing his sister-in-law. After being released from prison in 1894, he went to Colwell, Iowa, where he met thirty-one-year-old Alma Nesbitt. They traveled to Oregon and filed adjoining homestead claims twenty miles outside Hood River before being secretly married on July 25, 1899, in Vancouver, Washington.

Alma worked hard to improve her 149.35 acres by building a house and other small outbuildings. In October, her mother, sixty-nine-year-old Louisa J. Nesbitt, joined her. That winter the women moved to Portland, where Alma worked as a housekeeper.

On March 8, 1900, the trio boarded a Portland train for Hood River. When they arrived that evening, Williams rented a wagon, and they headed to their homestead. That was the last time either woman was seen alive.

Daniel Williams soon encountered two problems: marriage did not give him the right to Alma’s land, and his house and barn had been mistakenly built on Alma’s claim. In desperation, he forged Alma’s name on a relinquishment and presented it to the land office on June 23, 1900. An employee recognized that Alma’s signature was a forgery, and the federal court issued an indictment for D. Norman Williams.

In early 1904, George Nesbitt arrived in Oregon to investigate the disappearance of his mother and sister. While digging around on Williams’s property, he discovered bloody gunnysacks, chunks of long gray hair, and a piece of scalp with long brunette hair still attached.

The Wasco County grand jury issued an indictment for first-degree murder against Williams. He was arrested in Bellingham, Washington, and escorted to Hood River. An investigation revealed that he was still married to a wife in Nebraska and that two of his six wives had died of poison.

At the trial, which began on May 27, 1904, defense attorney Henry McGinn argued that there could be no murder without a body. Prosecutor Frank Menefee, however, had a surprise witness—Dr. L. Victoria Hampton, a young Portland chemist. She proved that the hair attached to the scalp was human and testified that it belonged to Alma Nesbitt. Using the new “serum” test that had been discovered in Germany a year earlier, Dr. Hampton established that the blood on the gunnysacks was from a human being, not an animal.

After the guilty verdict was appealed and upheld, the Oregon Supreme Court stated: “Where, as here, the circumstances point with one accord to the death of the person alleged to have been murdered, the finding of fragments of a human body, which are identified as part of the body of the alleged victim will be sufficient, if believed by the jury, to establish the fact of death when this is the best evidence that can be obtained under the circumstances.”

On July 21, 1905, Daniel Norman Williams was the sixty-sixth and last man publicly hanged in Oregon.

-

![]()

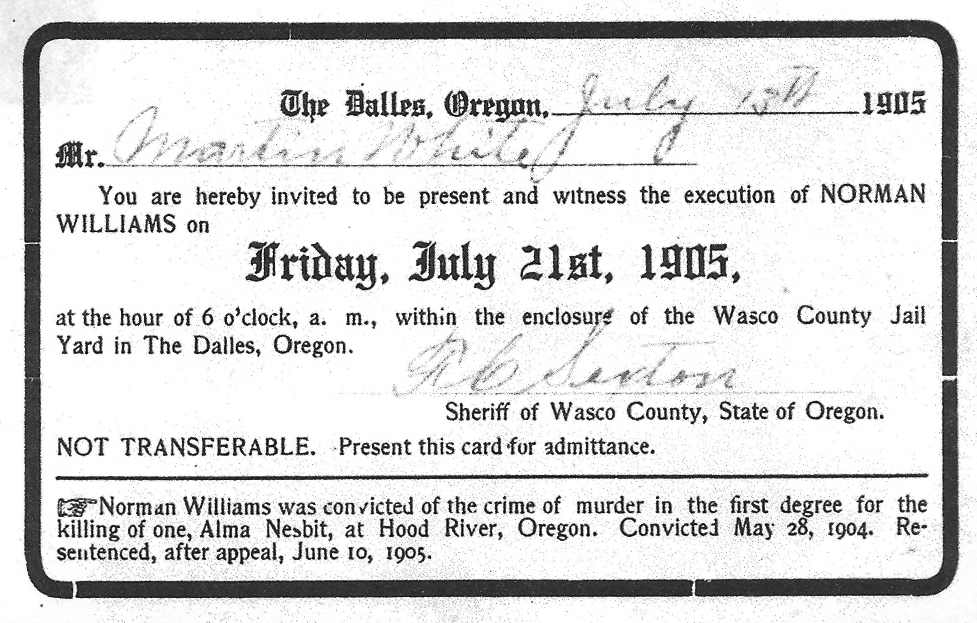

Invitation to view hanging of Norman Williams.

Courtesy Oregon State Sheriff's Association -

![]()

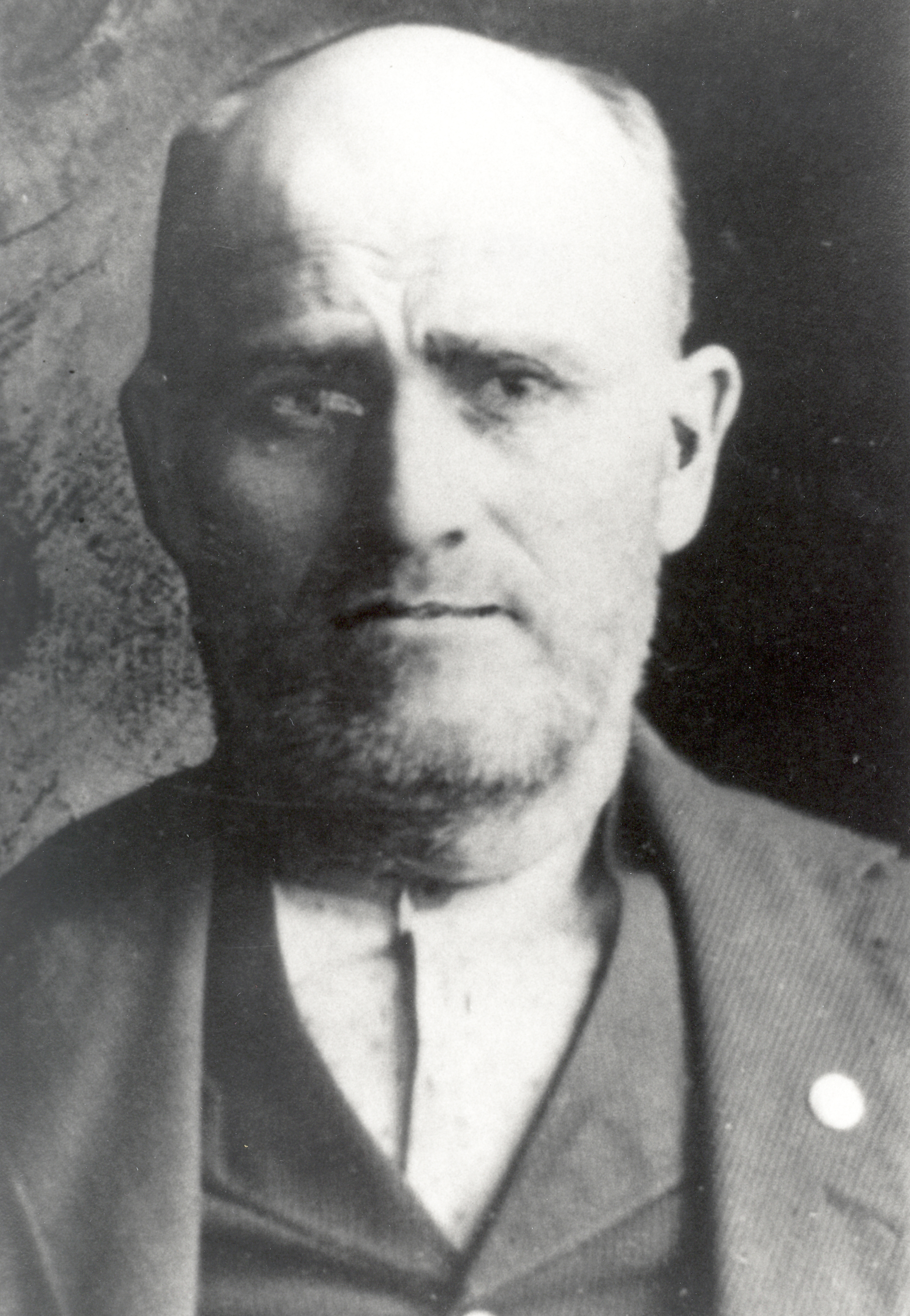

Norman Williams, c.1904.

Courtesy Oregon State Sheriff's Association

Related Entries

-

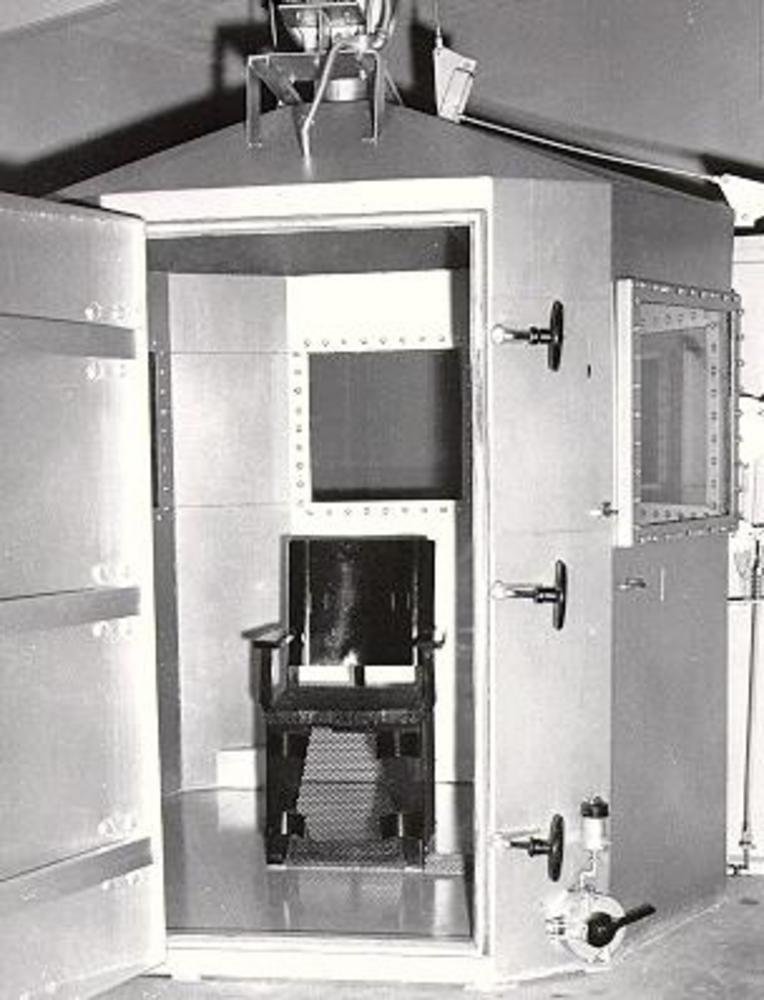

![Death penalty]()

Death penalty

Oregon has had a death penalty for most of its history as a state, thou…

-

![State of Oregon v. Phillip George]()

State of Oregon v. Phillip George

Oregon’s reputation for showing respect for the common citizen and indi…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Goeres-Gardner, Diane L. Necktie Parties: The History of Legal Executions in Oregon, 1851-1905. Caldwell, Id.: Caxton Press, 2005.

Holbrook, Stewart. Wildmen, Wobblies and Whistle Punks. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1992.