Oregon’s reputation for showing respect for the common citizen and individualism began early in its history. The execution of Phillip George in 1860 is an example of how that reputation was earned and how that respect was carried out in the political arena.

Phillip George, a German immigrant, was the fifth man executed in the year after Oregon became a state. He and John Clark, his partner, had recently opened the American House, a boarding house in Corvallis. On March 10, 1860, in a fit of alcoholic rage and in front of several witnesses, George threw a stone at Clark, hitting him in the head and killing him. A Benton County circuit court jury heard the case and convicted George of first-degree murder. Judge R.A. Stratton sentenced him to hang on May 25, 1860.

Nearly two thousand people, including women and children, crowded the streets on the day of the hanging. Unknown to George or the spectators, Governor John Whiteaker, who had refused to sign a petition commuting George’s sentence to life imprisonment, had signed a thirty-day reprieve allowing time for Judge Stratton to consider commuting George’s sentence. But the reprieve, which had arrived by courier at eight that morning, lacked the legal counter signature of Secretary of State Lucien Heath. Quickly, a rider was sent to secure the signature, but Benton County Sheriff Sheldon B. Fargo knew that it was impossible to ride sixty-five miles in the six hours remaining before the hanging.

By one o’clock, the signed warrant still had not arrived, putting the sheriff in a legally precarious position. George was marched out of the jail under heavy guard and conveyed by open carriage to the gallows. Accompanied by two clergy—Reverend Fisher and Reverend Rayner, who led the crowd in a hymn and a prayer—he climbed the scaffold steps. In heavily accented English, George violated the precedent in which convicted murderers confess as they stand on the gallows. Instead, he denied his guilt in a lengthy and rambling speech.

Making his decision, Sheriff Fargo stepped forward and informed the crowd of the “not quite legal” reprieve that might be coming. Unwilling to choose whether they should go ahead with the execution or wait thirty days, he asked the crowd to decide. The sheriff believed that the citizens of Corvallis had the right and the intelligence to make the correct decision. He wanted them to vote.

It is easy to imagine the crowd’s confusion and disbelief as they surrounded the scaffold at the end of Second Street. Still, they voted to uphold and honor the governor’s reprieve and the Oregon Constitution that gave him the right to make that decision. George was taken back to jail.

This was Oregon’s first application of law by direct representation. In 1902, the Initiative and Referendum Act was added to the Oregon Constitution, part of a package of bills that would become known as the Oregon System. Phillip George was hanged on June 22, 1860.

-

![]()

Early sketch of Corvallis, 1858.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 4300

-

![]()

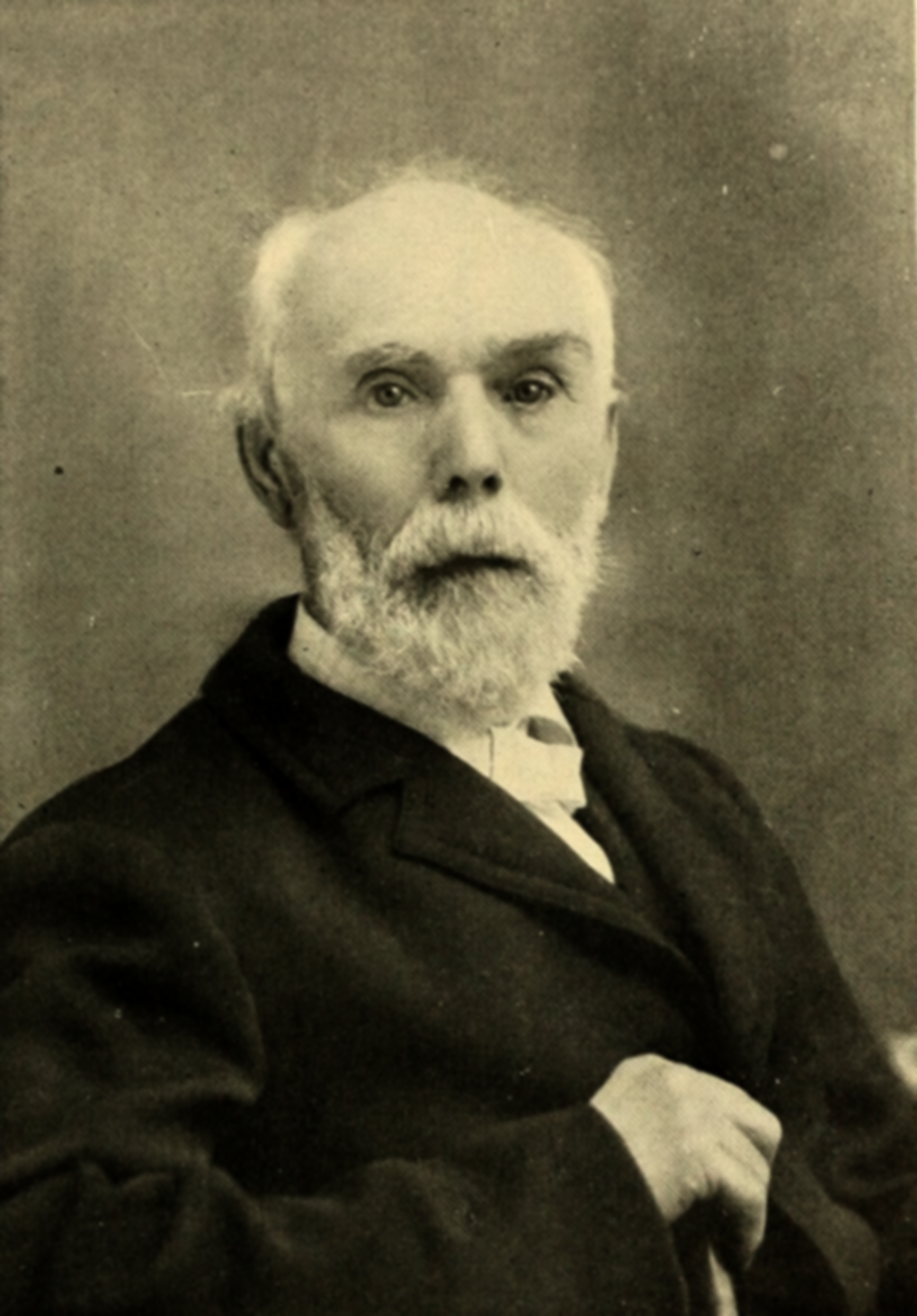

John Whiteaker, first Governor of Oregon, 1859-1862.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 018392.

Related Entries

-

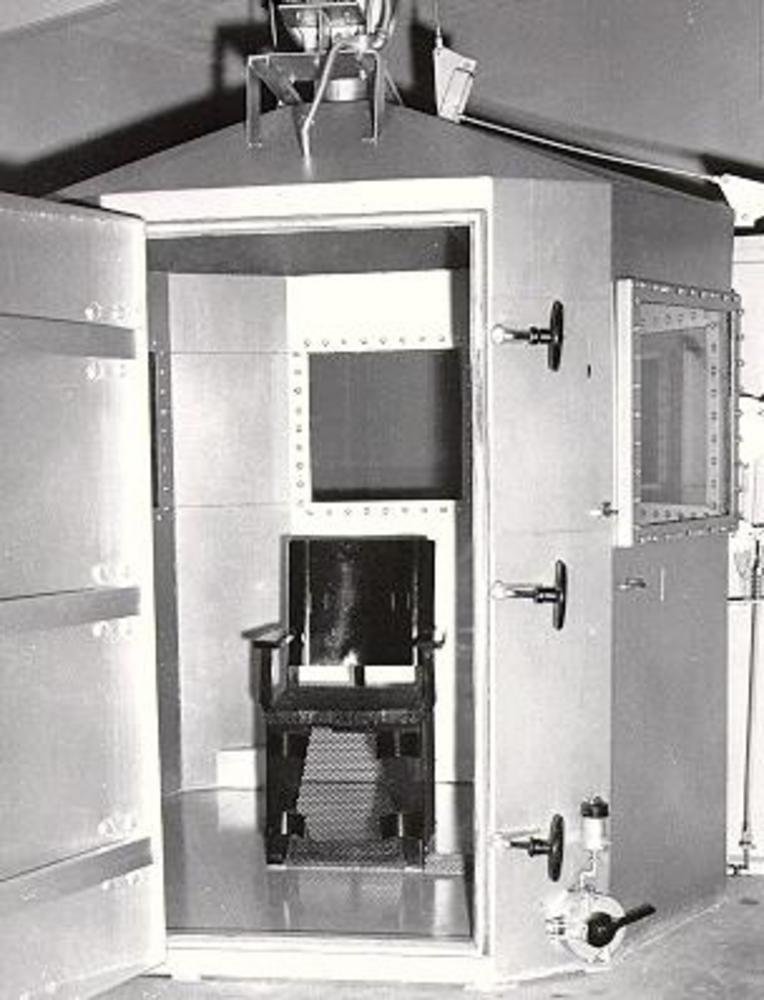

![Death penalty]()

Death penalty

Oregon has had a death penalty for most of its history as a state, thou…

-

![John Whiteaker (1820–1902)]()

John Whiteaker (1820–1902)

John Whiteaker, a self-educated farmer from Lane County, was elected in…

-

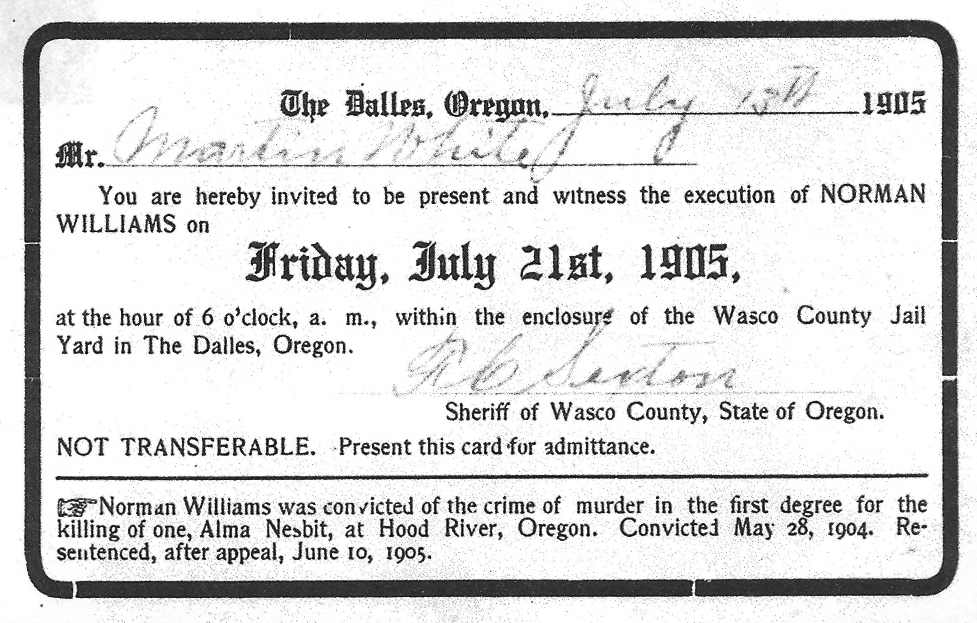

![State of Oregon v. Norman Williams]()

State of Oregon v. Norman Williams

In May 1904, in State of Oregon v. Norman Williams, an Oregon jury made…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Goeres-Gardner, Diane L. Necktie Parties: The History of Legal Executions, 1851-1905. Caldwell, Id: Caxton Press, 2005.