Marion Sayle Taylor was the Voice of Experience, a radio personality who appeared on national advice programs on the CBS, NBC, and Mutual stations from 1932 to 1940. To create his radio persona, he drew on his life in Oregon, where he had spent time in jail and taught school. His years in Oregon, from 1912 to 1926, were marked by educational and civic engagement, but during his later years he was dishonest, manipulative, and opportunistic. He told the Oregonian for the July 14, 1938, issue: “I think I’m a pretty good Oregonian, at least a pretty good ex-Oregonian.”

Marion Sayle Taylor was born in Morrilton, Arkansas, on August 16, 1889, to Addie Cason and Francis Taylor. As a boy, he traveled with his father, a Baptist preacher, playing the organ and preaching at services. To prepare for the ministry, he enrolled at William Jewel College in Liberty, Missouri. He left the college in 1908 after his junior year, likely in rebellion against his authoritarian father.

Taylor moved to the West, where he drifted from place to place. In 1910, he was arrested in The Dalles for passing bad checks, joined in a breakout from the city jail, and was captured and sent to the Oregon State Penitentiary. Paroled by Oswald West on September 12, 1911, he was released from parole the following June as part of the governor’s efforts to reform the penal system by releasing promising young people from jail. Taylor then enrolled at Pacific University in Forest Grove, graduating in 1912. While working as a cashier in G. W. Moore & Sons meat market, he met Freda Pauline Moore, his employer’s daughter, who he married in 1914. They had one child.

During the 1914-1915 school year, Taylor taught at Newport High School and assisted Portland’s Ellison–White Chautauqua program, which produced lectures and musical programs in nine summer circuits in western states. From 1915 to 1918, he taught music and science at Klamath Falls High School and helped promote war bonds for the county’s liberty chorus, a statewide program supported by the State Council of Defense for Oregon.

From 1918 to 1920, Taylor was the superintendent and high school principal of Amity Schools, where he started a parent-teacher group. He wrote by-laws for Amity’s Community Commercial Club and in 1920 joined the Ellison–White Chautauqua circuit as a manager and lecturer. In 1922, he was named principal of the high school in Marshfield (now Coos Bay), where he was also vice president of the Kiwanis and a supporter of the Coos Bay band and other cultural programs.

Taylor helped create a booster organization, the Coos Bay Pirates, in 1923, and the Oregon Hospitality Clubs selected him as its president in 1925. While serving as superintendent of schools in North Bend, he chaired the first Community Chest campaign and helped secure a 1923 bond passage for constructing the Roosevelt School. He also managed the Hotel North Bend. He was involved in at least one affair, and in early 1925, the Taylors divorced. Taylor resigned as school superintendent in 1926 and left Oregon, possibly to flee rumors that he was involved in fatally poisoning his friend and business partner Price Westover in a life insurance scheme.

He then turned his talents to staging theater presentations on married life. He published a booklet, The Male Motor, and pamphlets on Sex Vigor: How Retained, How Regained and Facts for Wives: Plain Truths about Marriage. He went on tour, claiming that he had a Ph.D. and marketing “health devices” that were condemned by the American Medical Association. In 1929, he married Jessie Westover, the widow of his friend Price Westover. When sales of the health devices declined, he turned to work on the radio.

In 1932, Taylor created the Voice of Experience on WOR Radio in Newark, New Jersey, giving advice and replying to listeners’ questions. CBS picked up the program and kept him on as the host. Boosted by 1933 print ads declaring that he was “Radio’s Greatest Star,” Taylor and various press accounts claimed that he drew more mail than any other radio personality. In May 1936, the program moved to NBC; the next year Taylor joined the Mutual Broadcasting System. Voice of Experience led to the publication of five books, a series of pamphlets, and a magazine (1936). Ten-minute Voice of Experience films were screened in theaters.

The radio programs encouraged charitable contributions, and annual Christmas appeals brought in boxcars of fruit. Taylor contributed to children’s hospitals and claimed, without verification, that the donated sums were spent on surgeries, eyeglasses, and dental work for adults. It has been verified that he contributed $100 to Bandon, Oregon, fire relief in 1936. He returned to Oregon in 1938 to speak in McMinnville and Marshfield (Coos Bay).

Taylor embellished his biography with deceptions in interviews and promotional materials. He concealed his jail time, created a new birthplace (Louisville, Kentucky), fictionalized time in San Francisco and Seattle, and falsely reported that he had studied at several universities. He claimed that Pauline, his first wife, had died in childbirth. In 1935, he told his second wife that Pauline was suing him for alienation of affection. Taylor’s remedy was to divorce Jessie, promising to remarry her once the suit had been settled. Instead, he married Mildred Manska in 1936; they would have two daughters. When Jessie Taylor learned about Mildred, she sued Taylor in 1940 and declared that the divorce should be annulled. They settled the case, but Taylor’s radio image as a reliable marriage counselor was damaged, and by the end of the year only a few stations, including KGW Portland, carried his program. When his last remaining sponsor, Albers Brothers Milling Company, canceled its support, the show—along with Taylor’s livelihood—ended.

On February 1, 1942, Taylor suffered a heart attack and died in Hollywood, Los Angeles. His family received a small life insurance policy, and creditors claimed the $23,000 he left as assets. The Oregonian detailed Taylor’s many deceptions in an article published after his death, ending with: “The Voice of Experience was apparently just as befuddled as the bewildered millions who sought his advice.”

-

![]()

Taylor with CBS microphone. CBS News Photo Department press photo, 1934.

Courtesy Dick and Judy Wagner

-

![]()

The Voice of Experience Radio Show, pamphlet, by Taylor, 1933.

Columbia Broadcasting System

-

![]()

Taylor in a white Panama hat.

Courtesy Nancie and Julie Taylor

-

![]()

"Helped Thousands Find Happiness--While He Got into Trouble," Sunday Oregonian, 1942.

Portland Sunday Oregonian, March 15, 1942

Related Entries

-

![Amity]()

Amity

Amity is situated in southern Yamhill County along Salt Creek near its …

-

![As It Was (Jefferson Public Radio)]()

As It Was (Jefferson Public Radio)

Jefferson Public Radio (JPR), a network of satellite radio stations ser…

-

![Coos Bay]()

Coos Bay

The Coos Bay estuary is a semi-enclosed, elongated series of sloughs an…

-

![Jefferson Public Radio]()

Jefferson Public Radio

Owned by and operating from the campus of Southern Oregon University in…

-

![KBOO Community Radio]()

KBOO Community Radio

In 2008, KBOO Community Radio (90.7 FM) celebrated forty years on the a…

-

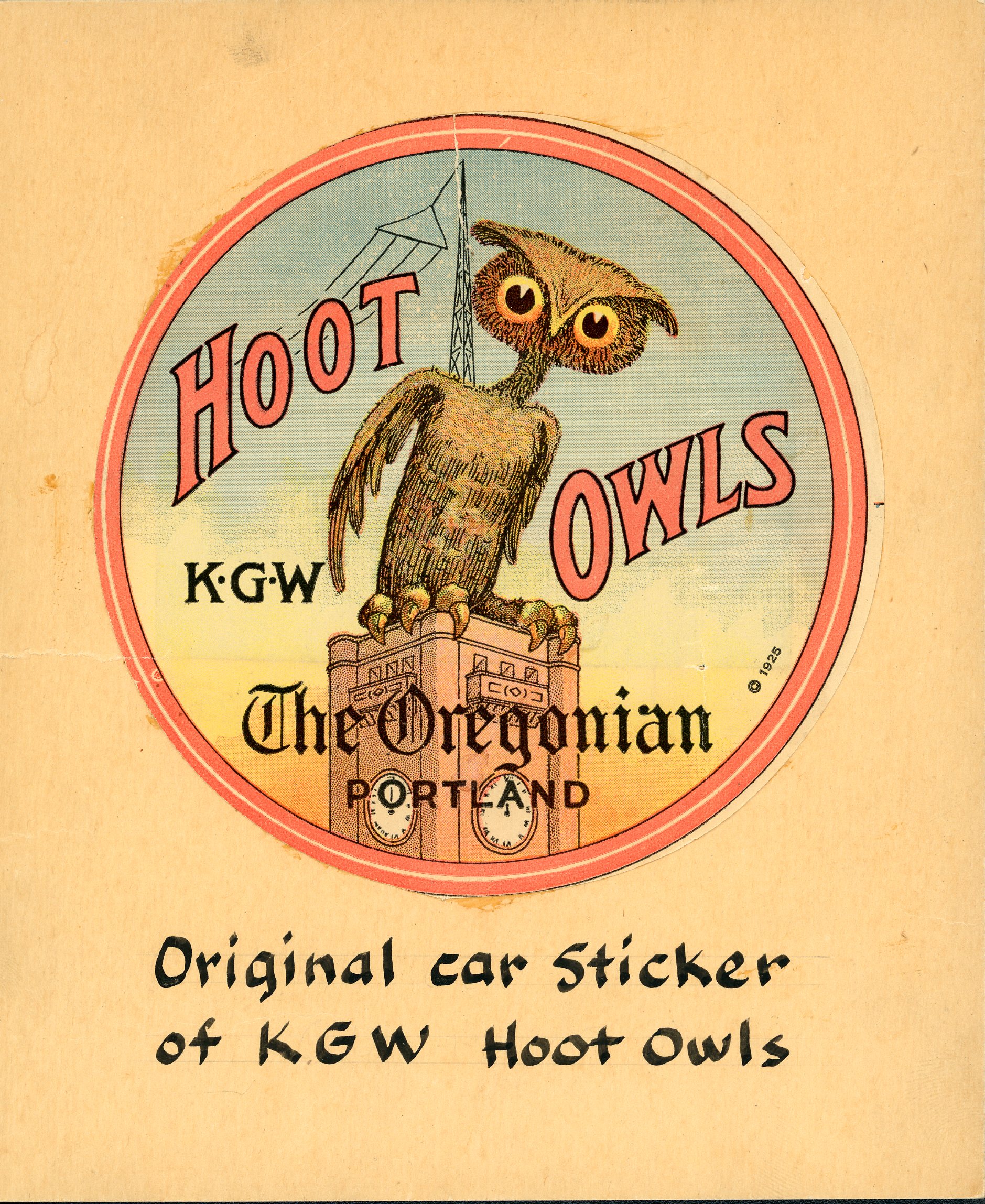

![KGW Hoot Owls]()

KGW Hoot Owls

The Portland Oregonian launched KGW Radio in March 1922. Nine months la…

-

![Mel Blanc (1908-1989)]()

Mel Blanc (1908-1989)

Mel Blanc, who acted the voice of Bugs Bunny and over four hundred othe…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Atkinson, Carroll. I Knew the Voice of Experience. Boston, Mass.: Meador Publishing Company, 1944.

Wagner, J.R. and J.K., Lies, Sex and Radio, Story of M. Sayle Taylor The Voice of Experience, North Bend, Ore.: Coos County Historical Society, 2013.

"North Bend Educator Resigns." Portland Sunday Oregonian, January 17, 1926.

"Insurance Fraud Hint in Marshfield Death Inquiry." Medford Mail Tribune, March 5, 1926.

"'Voice of Experience' Addresses 700 People Here." Coos Bay Times, July 15, 1938.

"Radio Figure Dies Suddenly: M. Sayle Taylor Known as 'Voice of Experience.'" Norfolk Ledger-Star, February 2, 1942.

"Helped Thousands Find Happiness--While He Got into Trouble." Portland Sunday Oregonian, March 15, 1942.