Among early migrants to the Oregon Country from the United States, Elijah White was remarkable for his role in shaping Oregon’s political culture. As a physician at the Willamette Mission, he established an early medical service. He also was a subagent to Native tribes, led the first large overland wagon train journey to Oregon, and petitioned Congress for aid to Oregon. Historians have been critical of White’s actions and attitudes, calling him a “schemer” and “a transparent opportunist”; an anthropologist portrayed him as “a contentious sort and somewhat of a flimflammer.” The characterizations are likely justified, but there is no ignoring that his actions as a vocal proponent of U.S. government sovereignty in Oregon and as a willful Indian agent helped shaped relations between Plateau tribes and white authorities during the 1840s and 1850s.

Elijah White was born in New York in 1806. He took medical training in Syracuse at Geneva Medical College, completing a degree in 1836. That year, he responded to the call by missionary societies for physicians to aid Christian evangelists who worked to convert Native people in the Oregon Country. White, his wife Sarepta, and their two children traveled on the Diana from New York to Hawaii and Astoria and arrived at the Willamette Mission by river canoe in May 1837.

Opinionated and headstrong, White involved himself in missionary politics. He contested mission founder Jason Lee’s leadership, criticizing his methods and management. Friction between the two increased by 1838, when Lee returned east to recruit reinforcements and secure financial support for the mission. When Lee returned in spring 1840 on the Lausanne with fifty new missionaries—known as the Great Reinforcement—White picked up his quarrel with him and Lee dismissed him from the mission staff. Disgruntled and determined to defend himself, White left in June 1840 aboard the Lausanne for New York, where he lobbied the missionary board of the Methodist Episcopal Church to give him a role in Willamette Mission finances. The Board refused that request, but it evidently listened to White’s criticisms and ousted Lee from the mission in 1843.

White had more success with a petition he carried to the U.S. Senate for military and political recognition from Americans in the Willamette Valley. Although the petition failed, White had alerted senators that a migration to Oregon had begun. He also used a political connection, perhaps Senator Lewis Linn of Missouri, to wrangle an appointment as a subagent for territories west of the Continental Divide. He raised funds in the East for the mission and encouraged more missionaries to trek to Oregon.

In May 1842, White led the first large wagon train on the Oregon Trail—114 people and 19 wagons—arriving in Oregon in August. Sarepta White remained in New York, perhaps because two of their children had died from accidental drowning during her two-year residence at Willamette Mission. Elijah White received a tepid welcome when he returned to the mission, but others in the valley cheered that the federal government had sent him as the first official in Oregon. He took up his role as Sub-Agent of Indian Affairs, West of the Rocky Mountains, at Oregon City in fall 1842.

In November 1842, White visited Plateau tribes east of the Cascade Mountains to investigate conflicts between whites and Indians. He went to Marcus Whitman’s mission at Waiilatpu and then to the Presbyterian mission at Lapwai, where he persuaded Nez Perce leaders to adopt an eleven-point “code of laws” to govern Native behavior. The code focused on property crimes, although murder headed the list of “articles” and merited hanging without due process. Most crimes carried the punishment of whipping, and White appointed “whippers” among the Nez Perce to mete out lashings to the guilty.

The code sowed problems, however. In spring 1843, White introduced his code to Cayuse and Walla Walla chiefs and to Wascos, who soon complained that whites ignored the laws or only used them against Indians. White’s activities sufficiently concerned John McLoughlin, chief factor at the Hudson’s Bay Company in Vancouver, that he instructed his agents at Walla Walla to resist White’s attempts to apply U.S. government policies. McLoughlin’s concerns aside, he found in White a defender of HBC policies toward Natives. White's desire to adjudicate disputes between Natives and whites led him to involve himself in the Cockstock Affair, a public fracas in Oregon City in April 1843 that resulted in the deaths of two whites and a Molala man.

White’s activities as a representative of the U.S. government included his participation in the Committee of Twelve, which held meetings that led to the establishment of the Provisional Government in 1843. In spring 1845, White also carried a petition requesting U.S. government approval of the Provisional Government; the petition failed. He did not involve himself in Oregon matters again until he returned to the region and pursued real estate ventures on the lower Columbia River in 1850. He received a second appointment as a subagent for tribes west of the Continental Divide in 1861 and moved to the San Francisco area. Elijah White died in California in April 1879.

-

![]()

Elijah White.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi728

-

![]()

Sarepta White, c.1851.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 39271

-

![]()

"Concise View of Oregon Territory, its Colonial and Indian Relations," by Elijah White, 1846.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi661

-

![]()

Letter from White to L.H. Judson, Nov. 21, 1843, regarding the handling of a Native American prisoner (first page).

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss 976, folder 1

-

![]()

Letter from White to L.H. Judson, Nov. 21, 1843, regarding the handling of a Native American prisoner (second page).

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss 976, folder 1

Related Entries

-

![Cockstock Incident]()

Cockstock Incident

The Cockstock Incident in 1844, also known as the Cockstock Affair, was…

-

![Great Reinforcement (1840)]()

Great Reinforcement (1840)

One of the signal immigrations to Oregon came by sea in 1840, years bef…

-

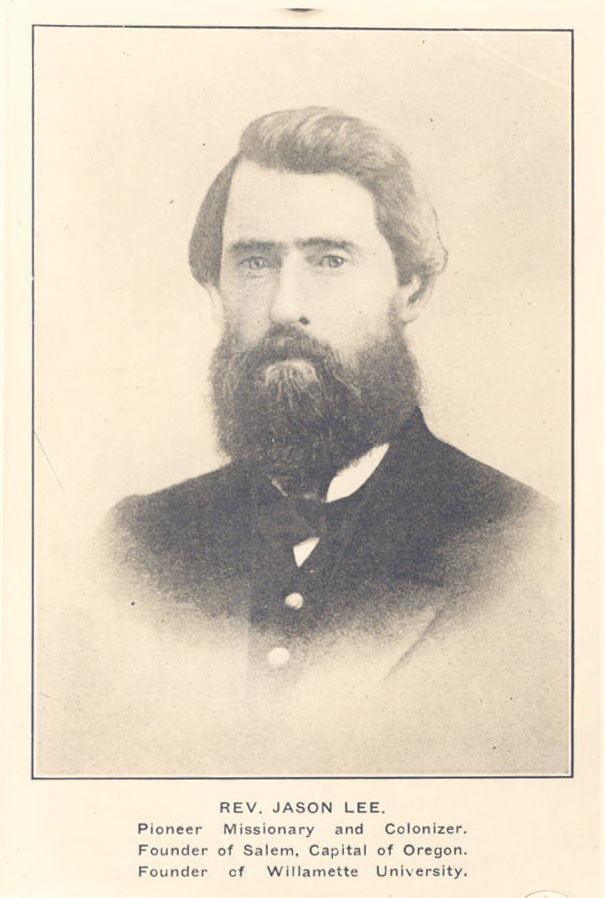

![Jason Lee (1803-1845)]()

Jason Lee (1803-1845)

Few names in the history of early nineteenth-century Oregon are better …

-

![John McLoughlin (1784-1857)]()

John McLoughlin (1784-1857)

One of the most powerful and polarizing people in Oregon history, John …

-

![Marcus Whitman (1802–1847)]()

Marcus Whitman (1802–1847)

Marcus Whitman left his mark on Oregon Country as an early missionary t…

-

![Oregon Rangers]()

Oregon Rangers

The Oregon Rangers, an organized militia based in Oregon’s Willamette V…

-

![Petitions to Congress, 1838-1845]()

Petitions to Congress, 1838-1845

Even before the first large wagon trains traveled the Oregon Trail to t…

-

![Provisional Government]()

Provisional Government

The Provisional Government, created in May-July 1843, was the first gov…

-

![Willamette Mission]()

Willamette Mission

Willamette Mission was the first noncommercial agricultural community e…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Boyd, Robert. People of The Dalles: The Indians of the Wascopam Mission. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

Gatke, R.M. Chronicles of Willamette: The Pioneer University of the West. Portland, Ore.: Binfords & Mort, 1943.

Gray, W.H. A History of Oregon. San Francisco, Calif.: Bancroft, 1870.

Josephy, Alvin. The Nez Perce Indians and the Opening of the Northwest. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1963.

Loewenberg, Robert J. Equality on the Oregon Frontier: Jason Lee and the Methodist Mission, 1834-1843. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1976.

Rich, E.E. McLoughlin’s Fort Vancouver Letters, Second Series, 1839-1844. Toronto: The Champlain Society, 1943.

Stern, Theodore. Chiefs and Change in the Oregon Country: Indian Relations at Fort Nez Perces, 1818-1855. Vol. 2. Corvallis: Oregon State University, 1996).