Native History is Oregon History

A resource for students and teachers

The history of the State of Oregon is short; the history of people in this place is much longer. A non-Native Oregonian can claim, at most, eight generations. Native Oregonians can claim hundreds. Early white settlers predicted that Native people would fade away and disappear from Oregon. They were wrong.

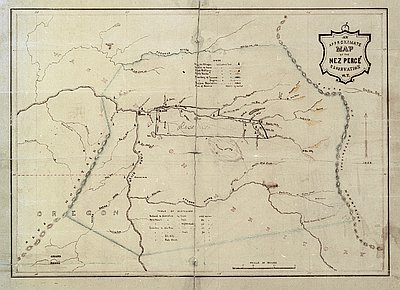

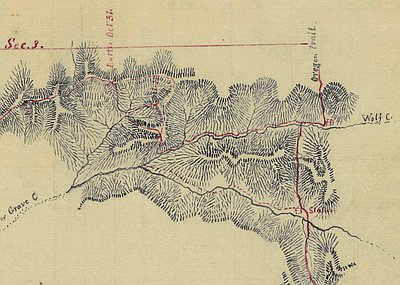

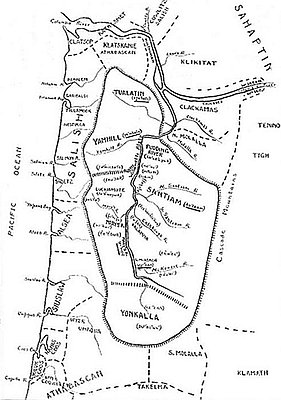

The United States government recognizes more than seventy tribes on nine reservations in the State of Oregon, a result of treaties ratified by Congress, executive actions taken by U.S. presidents, and adjudication by federal courts. Dozens of bands and tribes were confederated onto reservations, some of them far from traditional homelands.

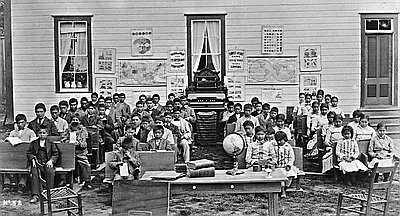

For many years, the U.S. government cut away at reservation boundaries. Then, in 1954, Congress targeted Oregon tribes with Public Laws 587 and 588, known as the Termination Acts, ending the trust relationships between the federal government and Native nations. Members of sixty-three Oregon tribes and bands at three reservations and other Native communities endured the deleterious effects of Termination, including the loss of their sovereignty, their land, and their community.

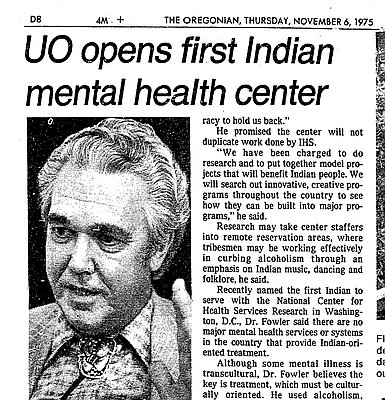

Beginning in 1972, some Oregon tribes gained back their sovereignty and their land trust rights with Restoration, legislation that was the result of years of advocacy. Since then, many tribes have had land returned by congressional acts and have purchased or negotiated for the land they lost, an effort that continues to this day. Some tribes continue to seek federal recognition. The experiences of Indigenous people in Oregon over generations, including those who were removed from the state, are essential to understanding the history of Oregon.

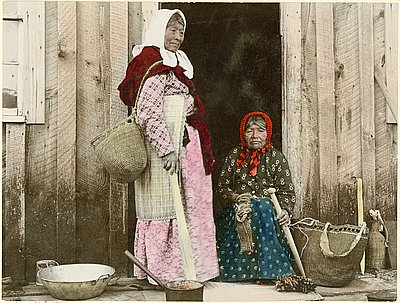

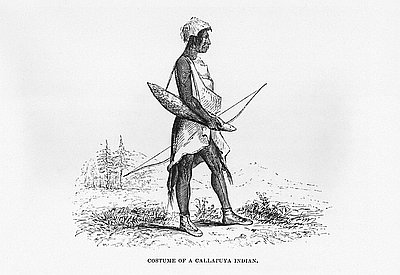

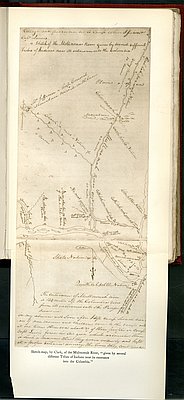

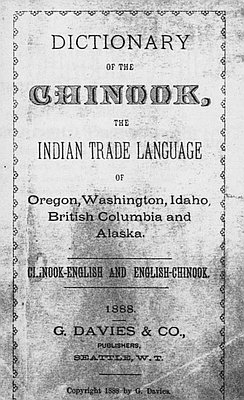

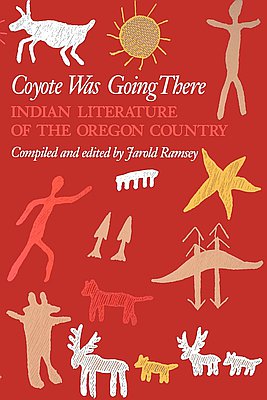

Most of the early written record of Native people in what became Oregon is from non-Natives who largely had limited interactions with Indigenous people and perceived them as culturally inferior. The result of this biased perspective generally obviated the histories that Native people have preserved for thousands of years through cultural practices such as oral traditions, placenaming, art, and ceremony. Today, Native historians and other scholars are generally committed to narrating a history that is honest, accurate, and revealing.