The Battle of Hungry Hill—also known as the Battle of Grave Creek—was the largest engagement of the Rogue River Indian War in 1855–1856. The battle took place on October 31 and November 1, 1855, in the Grave Creek Hills north of the Rogue River and west of the Oregon–California Trail. Combatants were three hundred to four hundred Takelma from the mid-Rogue River Valley against more than a hundred soldiers of the U.S. Army’s First Regiment of U.S. Dragoons and over two hundred Oregon Militia Volunteers. The war resulted from months of scattered conflicts between Indians who had left the Table Rock Indian Reservation near Jacksonville and whites who lived on homesteads or who were traveling through the region.

On October 8, 1855, in a shocking attack on an Indian encampment on Butte Creek near the reservation, vigilante raiders charged the camp before dawn and indiscriminately killed dozens of people—reportedly half of them women and children. The survivors fled to the reservation for protection. The event became known as the Lupton Massacre, after James Lupton, who led the attack.

In response, the traumatized Indians began a months-long war. When Takelma and others from Rogue River tribes raided white homesteads at widely dispersed sites in the Rogue River Valley, U.S. Dragoons at Fort Lane, led by Capt. Andrew Jackson Smith, went into the field with orders to defeat them. Col. John E. Ross, a local who prided himself as an “Indian fighter,” led the 9th Regiment of the Oregon Volunteers to bolster the force.

The dragoons and volunteers started out from Fort Lane, a U.S. Army post near the Table Rock Reservation. On October 8, an army scouting party located a Takelma encampment in the mountains, about six miles west of the Oregon–California Trail. Two U.S. soldiers were killed in a brief firefight. By October 30, reinforcement troops had arrived, and volunteers soon joined them at a rough, wooded area at 2,800 feet in elevation.

The officers’ plan included a coordinated encirclement of the Takelma camp by regular and volunteer companies, but poor communication and the difficulty of navigating the rough terrain forced them to make camp at a place that faced the Takelma who were encamped across a two-mile-long valley. Some of the volunteers lit campfires and one man accidently set fire to a tree, alerting the Takelmas to the dragoons’ and volunteers’ position. On the morning of October 31, as impatient troops moved across the valley toward the Takelma camp, women and children were led out of harm’s way and the men maneuvered their forces to take on the white combatants.

One volunteer later remembered seeing a woman on a horse—the daughter of Asperkahar (Chief Joe), who was called Mary or Sally—rallying Takelma as Colonel Ross sent his fighters up the steep canyon slope in attack. But the attackers hustled in such a disorganized manner, an eyewitness recounted in the Oregon Statesman, “that they threw their coats and blankets by the way-side, and the fleetest on foot were foremost…the first charge the most fatal to us.” Takelma combatants raked the oncoming soldiers with fire and moved to heavy brush for concealment. They held their position throughout the day, forcing the regular and volunteer forces to retreat at dusk.

The troops camped down the canyon slope in a wetland, where they experienced an uncomfortable night. They had abandoned their supplies, and many had no food or blankets—a condition that gave the Battle of Hungry Hill its name. On the morning of November 1, Takelma fighters attacked the white troops in a contest that continued for a few hours. The number of casualties listed by participants on both sides range, but at least thirty volunteers and ten regulars were killed or seriously wounded. Fifteen to twenty Takelma were killed or wounded.

The U.S. Army and the Oregon Volunteers had lost the Battle of Hungry Hill. Many people blamed the officers of the territorial militia for their errancy in strategies, tactics, and battlefield management. But in white communities, such as Jacksonville, Winchester, Corvallis, and throughout the southern Willamette Valley, the volunteer fighters became heroes, and criticism was leveled at the regular troops. Despite the outcome of the battle, fighting in the Rogue River Valley went on until May 1856, with the last conflicts taking place on the lower river.

Over the decades, as memories of the event faded, the location of the Battle of Hungry Hill was lost. In 2012, a team of archaeologists and historians organized by the Southern Oregon University Laboratory of Anthropology used textual records and modern technology to locate it.

-

![]()

A detail of the map of the Hungry Hill Battle site, drawn by Second Lt. August V. Kautz in October 1855..

Courtesy National Archives, RG 393

-

![]()

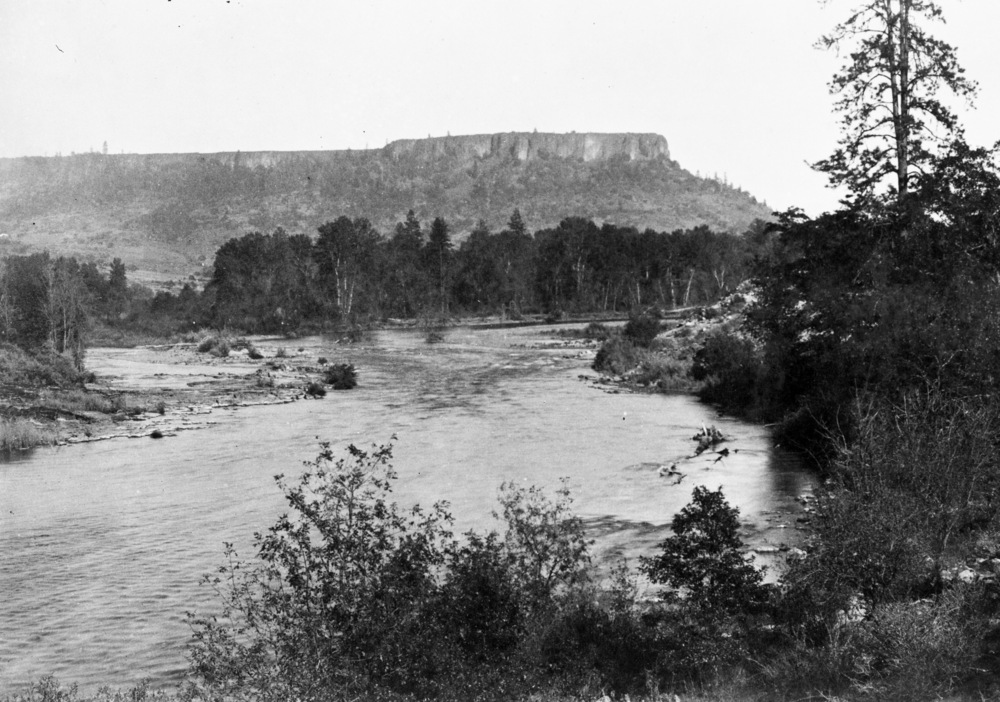

View from Grave Creek Hills toward Rogue River, near the battle site..

Courtesy Southern Oregon University Laboratory of Anthropology

-

![]()

A map of Southern Oregon in 1850, marking (among other places) Hungry Hill, the site of the Lupton Massacre, Fort Lane, and the Table Rock Reservation..

Courtesy Oregon Historical Quarterly, map by Jesse Nett

-

![]()

The view from Grave Creek Hills of the valley crossed by dragoons and volunteers on October 31, 1855..

Courtesy Southern Oregon University Laboratory of Anthropology

-

![]()

View of the Takelma defensive position, Hungry Hill Battle site..

Courtesy Southern Oregon University Laboratory of Anthropology

-

![]()

A gun powder container stopper and two .69 caliber lead musket balls found at the Hungry Hill Battle site..

Courtesy Southern Oregon University Laboratory of Anthropology

Related Entries

-

![Apserkahar (Chief Joe)]()

Apserkahar (Chief Joe)

In the 1850s, Apserkahar, also known as Chief Joe, led one of the two p…

-

![Fort Lane]()

Fort Lane

Fort Lane was a United States military fort constructed following the s…

-

![Rogue River]()

Rogue River

The Rogue River, Oregon’s third-longest river (after the Columbia and W…

-

![Rogue River War of 1855-1856]()

Rogue River War of 1855-1856

The final Rogue River War began early on the morning of October 8, 1855…

-

![Table Rock Treaty of 1853]()

Table Rock Treaty of 1853

The Council of Table Rock brought a temporary peace between Indigenous …

-

![Tecumtum (?-1864)]()

Tecumtum (?-1864)

Tecumtum, whose name means Elk Killer, was the principal chief of the E…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Schwartz, E. A. The Rogue River Indian War and Its Aftermath, 1850-1860. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1997.

Tveskov, Mark. “A ‘Most Disastrous’ Affair: The Battle of Hungry Hill, Historical Memory, and the Rogue River War.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 118.1 (2017): 42–73

Victor, Frances Fuller. The Early Indian Wars of Oregon. Salem, Ore.: Frank C. Baker, 1894.

Wilkinson, Charles, The People Are Dancing Again: The History of the Siletz Tribe of Western Oregon. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2010.