Peter Hardeman Burnett was a leader on the Oregon Trail, a town-builder, a legislator, and the region’s first judge. Throughout his professional career, he easily won people’s confidence and gained significant public positions, but he failed to provide effective leadership partly because he refused to take advice from others. His résumé was one of the most impressive in the early American West, but he resigned or was pushed from most of his positions. He is remembered in Oregon as the author of the first exclusion law banning Blacks from Oregon Country.

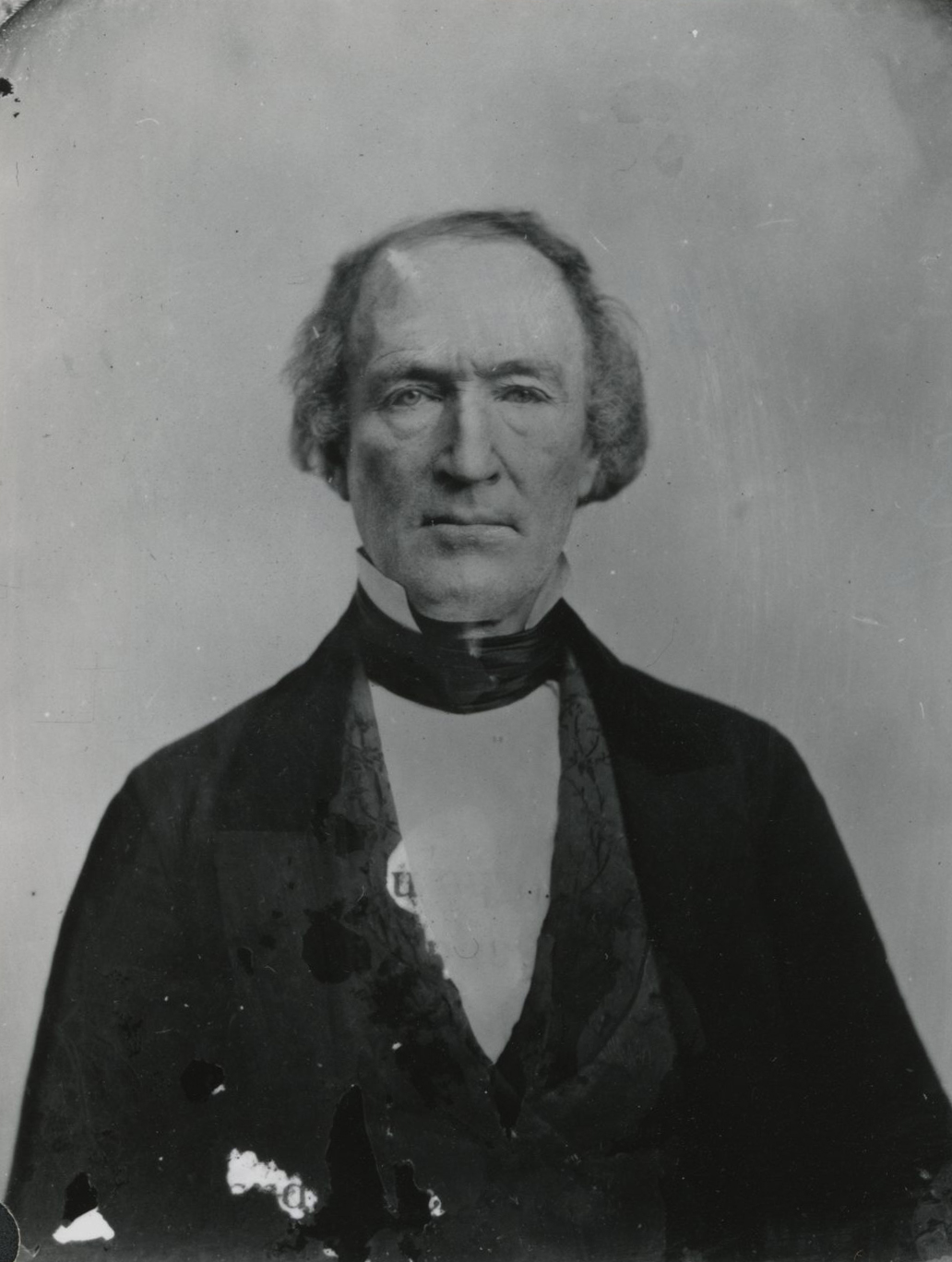

Burnett was born in Nashville, Tennessee, on November 15, 1807. He was raised in a family of slave owners and had two slaves of his own, a boy under age ten and a girl between the ages of ten and twenty-four. He married Harriet Rogers in 1828 and they had six children. As an attorney in Missouri, he represented Joseph Smith and other leaders of the Latter Day Saints (Mormons) accused of treason following the Mormon War in 1838.

In 1843, having failed as a merchant and heavily in debt, Burnett helped organize the first major wagon train to present-day Oregon, known as the Great Migration. Burnett was elected captain of the train, but resigned after just eight days, his leadership questioned by other emigrants who refused to follow his orders. The arrival of the group in the West—nearly nine hundred resettlers—more than doubled the white population of Oregon Country. John Minto, an 1844 emigrant, wrote that “no other single individual exerted as large an influence in swelling the number of home-building emigrants in Oregon in the years 1843 and 1844 as Peter H. Burnett.”

Soon after arriving in the Willamette Valley, Burnett and Morton McCarver, an emigrant from Iowa, planned the town of Linnton near the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers. They named the town for Senator Lewis Linn of Missouri and promoted it as a future major port. They miscalculated, however, and the major port developed a few miles up the Willamette River at Portland. It turned out to be a money-losing investment for both men, and Burnett relocated to the Tualatin Valley, where he bought a farm near present-day North Plains.

In 1844, Burnett was elected to the Oregon Provisional Government’s seven-member Legislative Council. He dominated the proceedings and wrote some of Oregon’s first laws. Most controversial was the exclusion law and its whipping penalty.

The 1844 law, an amendment to the Organic Law passed in 1843 by the Provisional Government, allowed a person to keep a slave in the Oregon Country for up to three years, after which the slave would be freed and required to leave. If the slave refused to leave, he or she would be subject to severe lashing. “The object,” Burnett wrote, “is to keep clear of that most troublesome class of population. We are in a new world, under the most favorable circumstances, and we wish to avoid most of those evils that have so much afflicted the United States and other countries.’’ The law is remembered today as “Peter Burnett’s lash law,” although it was amended within months to remove the lashing penalty. The law itself, the first of three exclusion laws in Oregon history, was dropped after a year. Burnett also opposed Chinese immigration to the region.

Burnett was appointed Oregon’s first judge in 1845, a position he held until 1847 when he resigned to go into legal practice. When Oregon achieved territorial status in 1848, he was elected to the first territorial legislature, but he soon resigned to join the gold rush to California. While in California, he learned that President James Polk had appointed him to Oregon’s Territorial Supreme Court, a position he turned down.

Working with John Augustus Sutter, the son of John Sutter, Burnett developed the city of Sacramento. He became wealthy selling property in that city and won election as California’s first elected governor in 1849. In that position, he tried unsuccessfully to persuade the legislature to enact an exclusion law for the new state. He resigned in January 1851 after his racist policies and other missteps subjected him to widespread ridicule.

Burnett was appointed in 1857 to a two-year term on the California Supreme Court, after which he went on to a successful banking career. He died in San Francisco on May 17, 1895. He is among the early Oregon leaders whose names are engraved on a frieze in the Oregon House of Representatives in Salem.

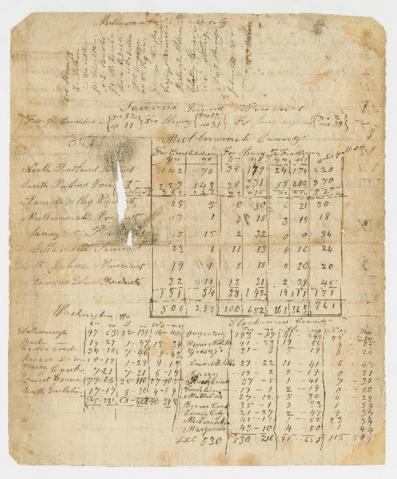

-

![]()

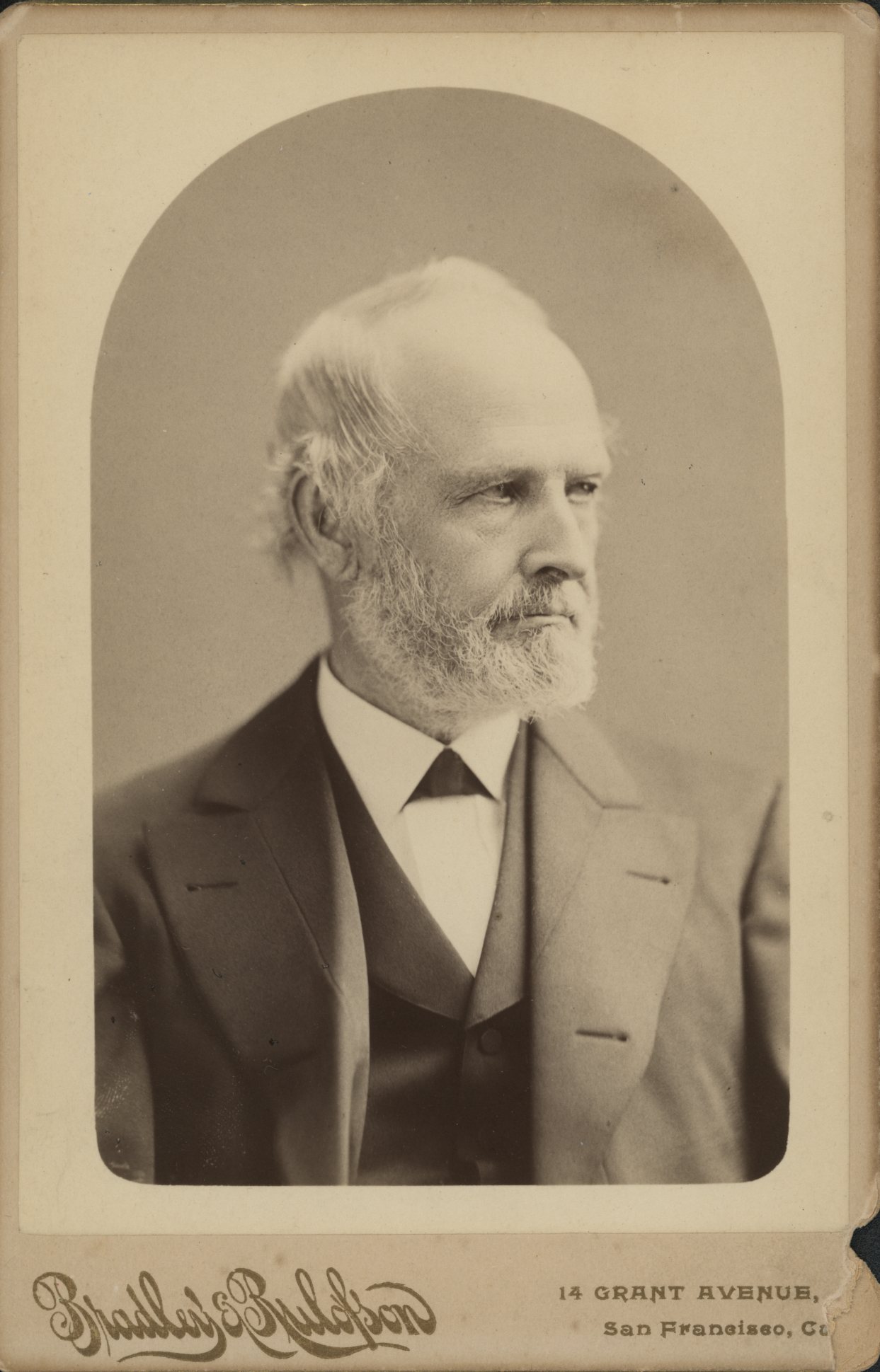

Peter Burnett.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi46162

-

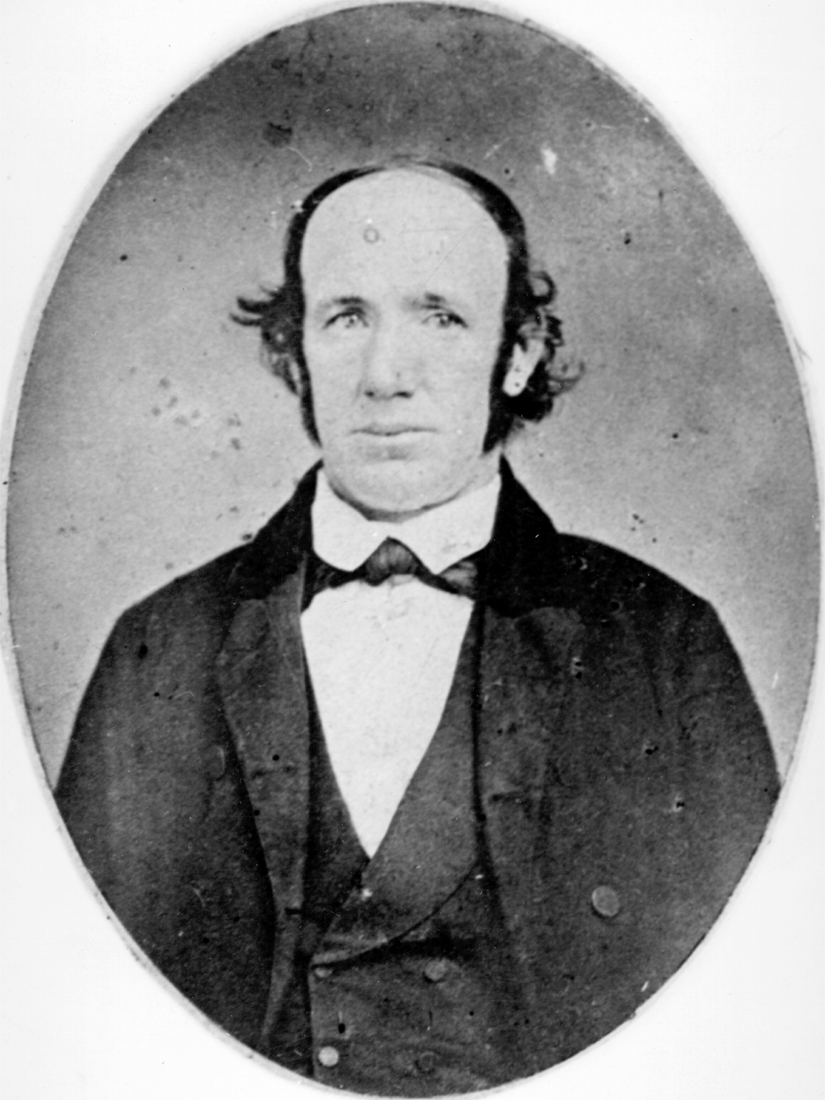

![]()

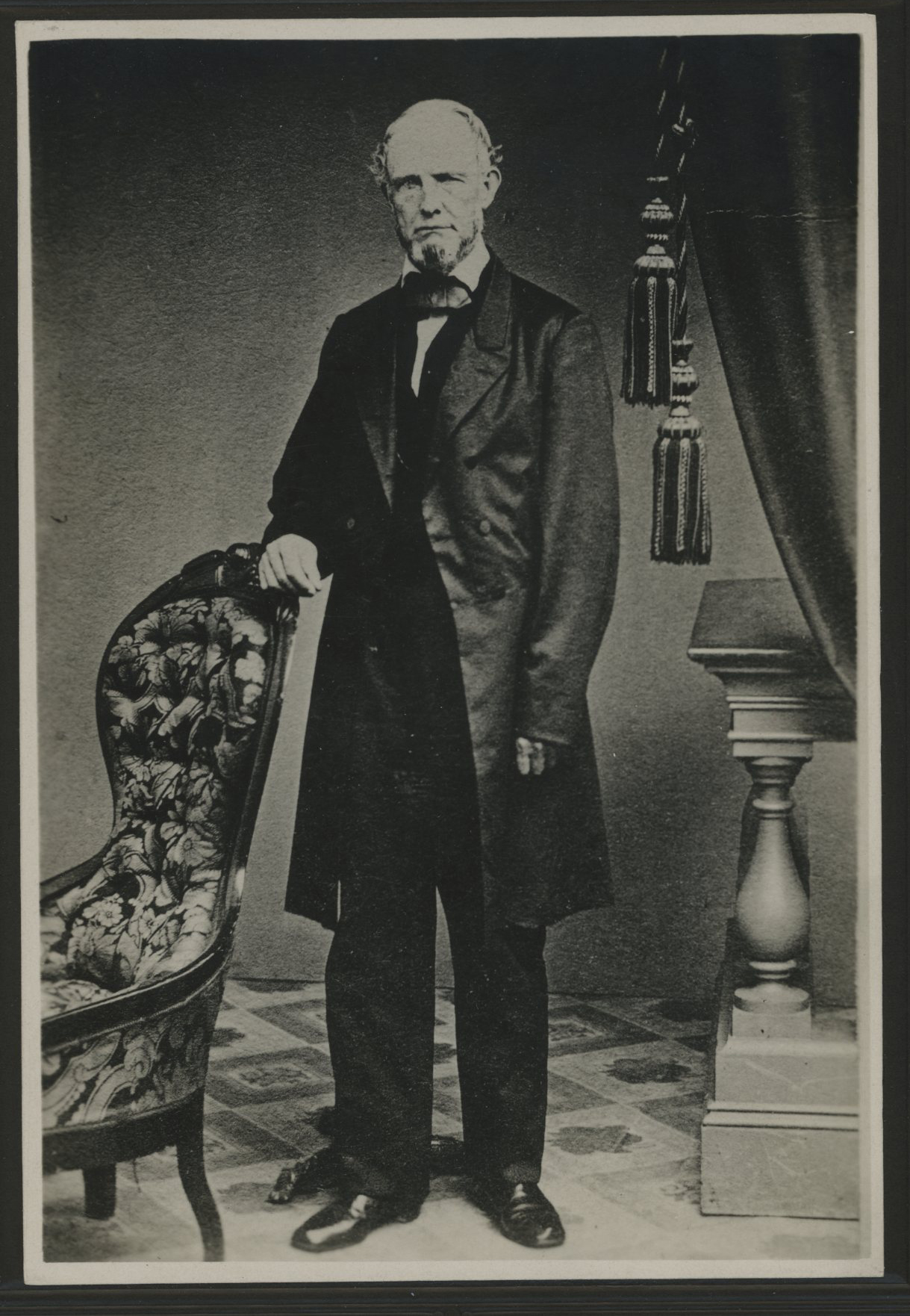

Peter Burnett, when he was governor of California.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi13424

-

![]()

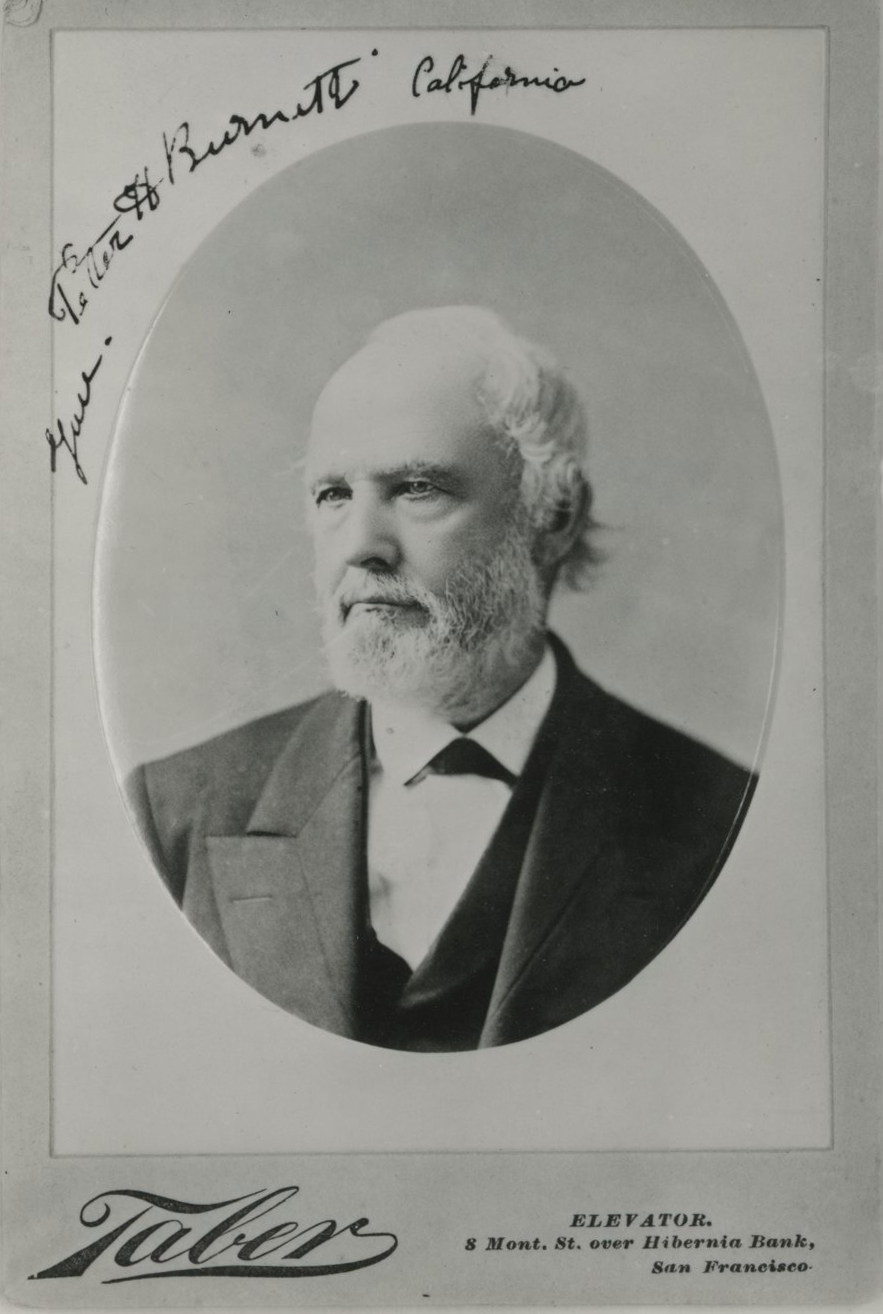

Peter Burnett.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 021773

-

![]()

Harriet Burnett.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 187

-

![]()

Morton McCarver.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi5360

Related Entries

-

![Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon]()

Black Exclusion Laws in Oregon

Oregon's racial makeup has been shaped by three Black exclusion laws th…

-

![John Minto (1822-1915)]()

John Minto (1822-1915)

John Minto described his sudden decision in 1844 to strike out for Oreg…

-

![Oregon Trail]()

Oregon Trail

Introduction In popular culture, the Oregon Trail is perhaps the most …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Burnett, Peter H. Recollections and Opinions of an Old Pioneer. New York: D. Appleton & Co, 1880.

Ford, Nineveh. "Pioneer Roadmakers," hand-written article dated June 17, 1878, microfilm, Oregon Historical Society Library.

Franklin, William E. "A Forgotten Chapter in California’s History: Peter H. Burnett and John A. Sutter’s Fortune." California Society Quarterly (1962).

Minto, John. "Motives and Antecedents of the Pioneers." Oregon Historical Quarterly (March 1904).

United States Federal Census Slave Schedule for Clay County, Missouri, 1840.

Nokes, R. Gregory. The Troubled Life of Peter Burnett: Oregon Pioneer and First Governor of California. Corvallis: Oregon State Univ. Press, 2018.

Quinn, Arthur. The Rivals: William Gwin, David Broderick, and the Birth of California. New York: Crown Publishers, 1994.