Henry Yelkus (also spelled Yalkus, Yelkes, Yelkis, Yal-kus, and Yelcus), a member of the Molalla Tribe, lived at Dickey Prairie, southeast of present-day Molalla, Oregon. His father, Kil-ke, also known as Chief Yelkus (Yelkas), was one of three signatories of the May 6, 1851, land-cession treaty at Champoeg and the 1855 Treaty with the Kalapuya, etc. at Dayton. In 1856, the Northern Molalla people, including Henry Yelkus, his older adopted sister Molala Kate, and members of thirty-three other tribes, were forced to walk sixty miles on a branch of Oregon’s Trail of Tears to Fort Yamhill, on the present-day Grand Ronde Reservation.

After years of being subjected to poor and crowded conditions and not having received the benefits verbally promised by Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer in 1856, many people left the Grand Ronde Reservation in the early 1860s to return to their ancestral homelands. Henry Yelkus and Molala Kate were among those who chose to leave, traveling with Molalla chief Siam Beavertrapper and his family back to Dickey Prairie.

By local accounts, the Molallas were welcomed back to Dickey Prairie by white resettlers, with whom they had established friendly relations. Such amicability had been fostered in 1848 when the local Molallas sided with the resettlers against Crooked Finger (Molalla) and his Klamath band during the Battle of Abiqua. But the way of life and land had changed in Dickey Prairie, and many Natives left again, unable to adjust to a landscape dominated by fences and plowed fields.

Like his sister Kate, Yelkus moved to Oregon City to find work, but after a few years he returned to Dickey Prairie, where he became an established figure in the community. According to one source, he was granted citizenship in 1869 (Indians were not considered citizens until the American Indian Citizenship Act of 1924) and in 1893 gained the title to the homestead he lived on.

Yelkus lived a mile up the north fork of the Molalla River on the property of a white resettler. He was the only tanner for the town of Molalla, and farmers and town residents went to him with hides of deer and other animals to turn into chamois. Wes Mitts, a Molalla resident who was a young boy at the time, recalled that residents paid Yelkus in cash or other commodities such as dried deer or calf brains, a tanning agent. Yelkus’s first wife, also a Molalla, made gloves and moccasins to sell.

In about 1880, Yelkus wanted to take Nellie Beavertrapper, the daughter of Chief Beavertrapper, as his second wife. He paid a bride-price of three horses and brought her into the home. His first wife, reportedly unhappy with the decision, became withdrawn, dressed herself in fine clothes, and disappeared. She was found three days later, having hanged herself on the bank of Dickey Creek.

Henry and Nellie Yelkus had one son, possibly adopted, named Dush-Wil-Guslik (also known as Fred), but their marriage did not last. Nellie left Henry in 1891 and married Harry Clark. Henry Yelkus continued to live at Dickey Prairie, and Dush-Wil-Guslik went to the Chemawa Indian School in Salem.

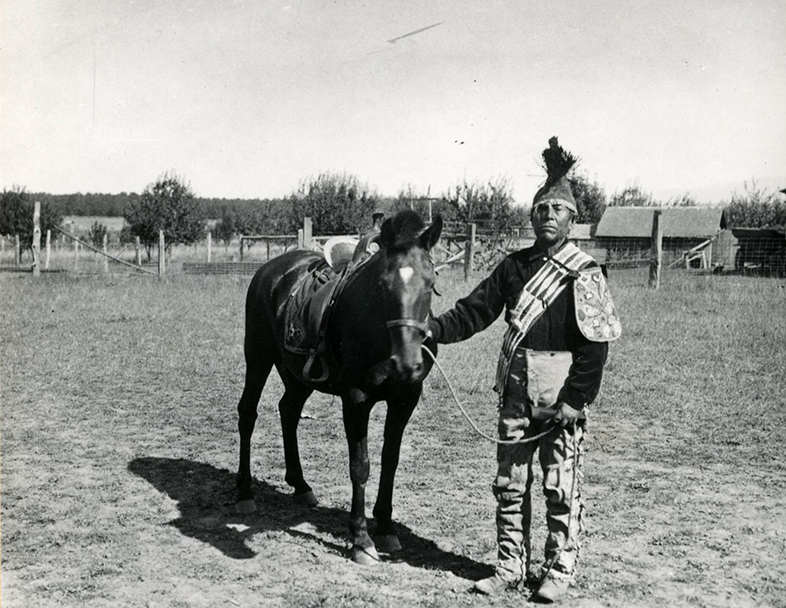

In 1913, the Oregon Pacific Railroad completed a section of rail line leading to the town of Molalla. The arrival of the first train on September 19 was cause for celebration, and Yelkus was invited to be the guest of honor. Adorned in his father’s regalia, he led the procession through town on his horse. “I was born here 67 years ago,” he told reporters. “I am the last of the Molalla Indians. They named this place from our tribe. When I was a boy there were many of my people here. Now they are all gone [moved to reservations]. My hat of deerskin and flicker feathers belonged to my grandfather. But he and the old times are gone.”

A few days later, Henry Yelkus was found dead along the road between Mount Angel and Molalla. It was reported that Harry Clark told authorities that he had taken sick and died, but the Oregon City sheriff took Clark into custody on suspicion of murder. He was acquitted by a jury a few months later.

Henry Yelkus was buried next to his first wife and his father at Dickey Prairie. Oregon newspapers widely reported the events of his death, falsely memorializing him as the “last of the Molalla.” The Molalla Pioneer marked the passing of “Chief Henry” as “the passing of a nation.” But Henry Yelkus was not the last of the Molalla people. Molallas and their culture continue through their descendants, who are members of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde and other tribes.

-

![]()

Henry Yelkus, 1912.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Drake Bros. Studio, Orhi46975

Related Entries

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![Kalapuya Treaty of 1855]()

Kalapuya Treaty of 1855

The treaty with the Confederated Bands of Kalapuya (1855) is the only r…

-

![Molala Kate Chantal (1844?-1938)]()

Molala Kate Chantal (1844?-1938)

Molala Kate Chantal (also known as Molala Kate)—the daughter of Molalla…

-

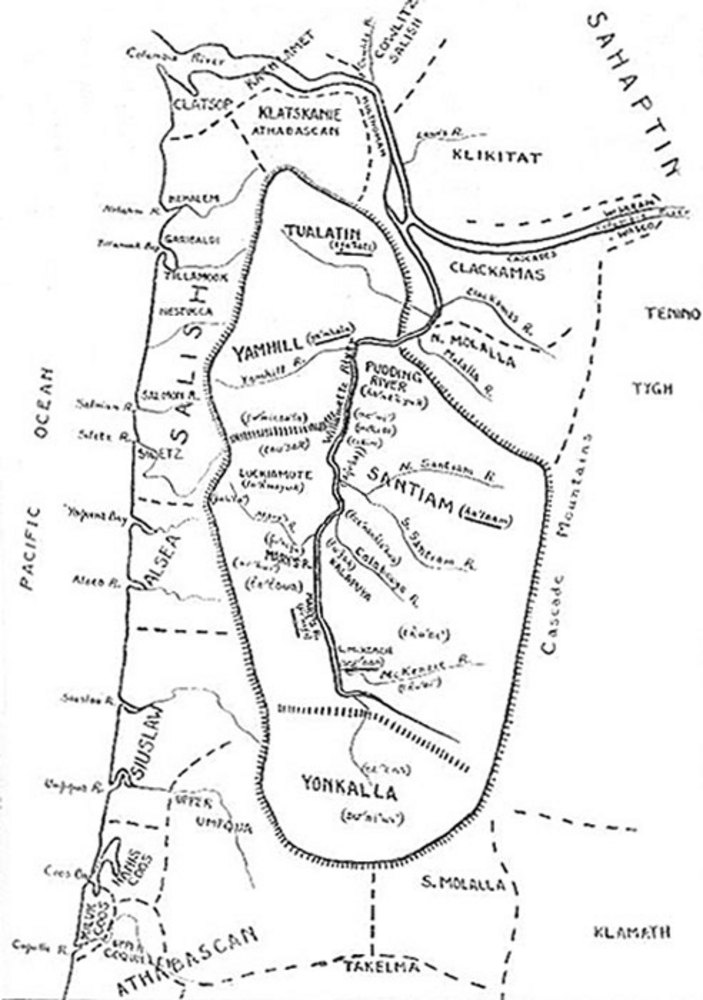

![Molalla Peoples]()

Molalla Peoples

The name Molalla ([moˈlɑlə, ˈmolɑlə], usually spelled Molala by anthrop…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaties]()

Willamette Valley Treaties

From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tri…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Baars, Patricia R. Near Neighbors: Cross-cultural Friendships in Dickey Prairie and South Molalla. Marylhurst, OR: Clackamas County Education Service District, 1982.

Beckham, Stephen Dow. "'Many Things Were Promised,' 1871." In Oregon Indians: Voices from Two Centuries. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2006.

Chapman, Judith Sanders., and Lois E. Helvey Ray. Molalla. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2008.

Hardy, Charles W., and Luther Cornay. Early History of Molalla and Nearby Areas: Memories of Charles W. Hardy. Molalla, OR: Charles W. Hardy, 1969.

“Indian Henry.” Molalla Pioneer, September 25, 1913.

McCormick, Gail J. Our Proud Past: A Compiled History of the Families that Settled at the End of the Oregon Trail. Mulino, OR: Gail J. McCormick Publisher, 1993.

Mitts, Wes. “Chief Yelkus, the One and Only Tanner in Molalla.” Molalla Area Historical Society. https://dibblehouse.org/molala-indians.html.

Olson, Kristine. Standing Tall: The Lifeway of Kathryn Jones Harrison, Chair of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2005.

Ruby, Robert H., and John A. Brown. "Molala." A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986, 194-197.

“The Last of the Molallas.” Molalla Bulletin Board, November 1, 1972.

Vaughan, Champ Clark. "Encounters with the Molalla Indian, 1848 to 1905." Molalla, OR: Molalla Area Historical Society, 2000.