From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tribes of western Oregon. Those treaties cleared the way for increased settlement by Americans and other immigrants into the Willamette Valley, as Native people were removed to reservations to eliminate conflicts and competition. This policy of removal helped create one of the most productive agricultural regions in the West.

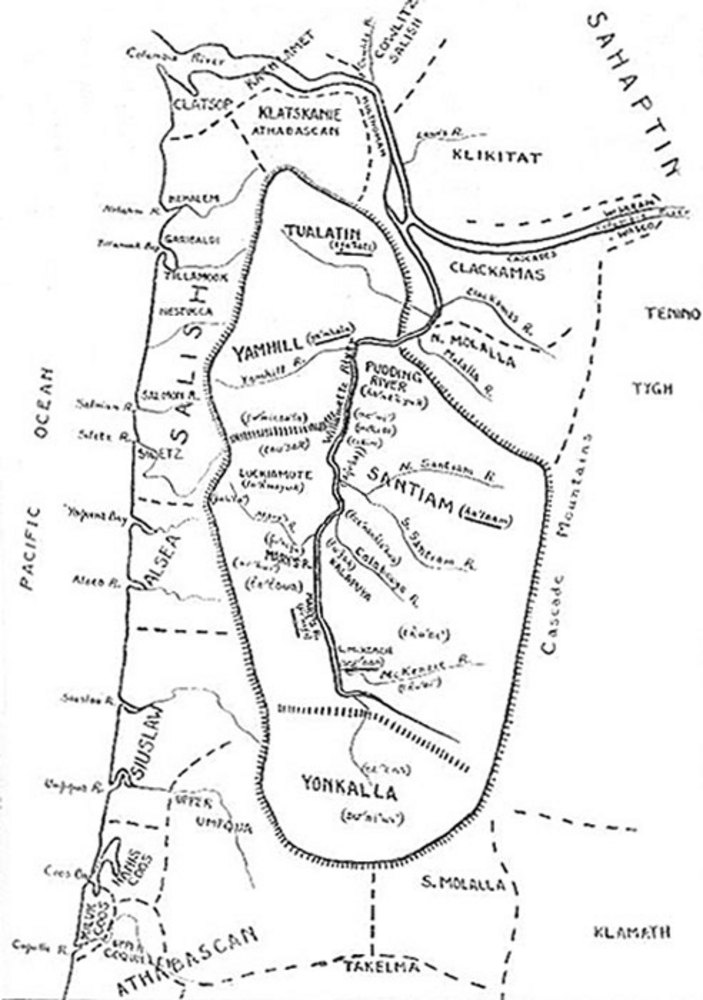

In the mid-nineteenth century, at least twenty tribes lived in the Willamette Valley, including the many tribes and bands of the Kalapuya peoples, several tribes of the Molala, and several tribes of the Chinook peoples. These peoples owned their lands and had defined homelands that had secured for them resources for gathering, hunting, and fishing for at least fourteen thousand years. That all changed when EuroAmerican explorers, traders, settlers, and miners ventured into the region.

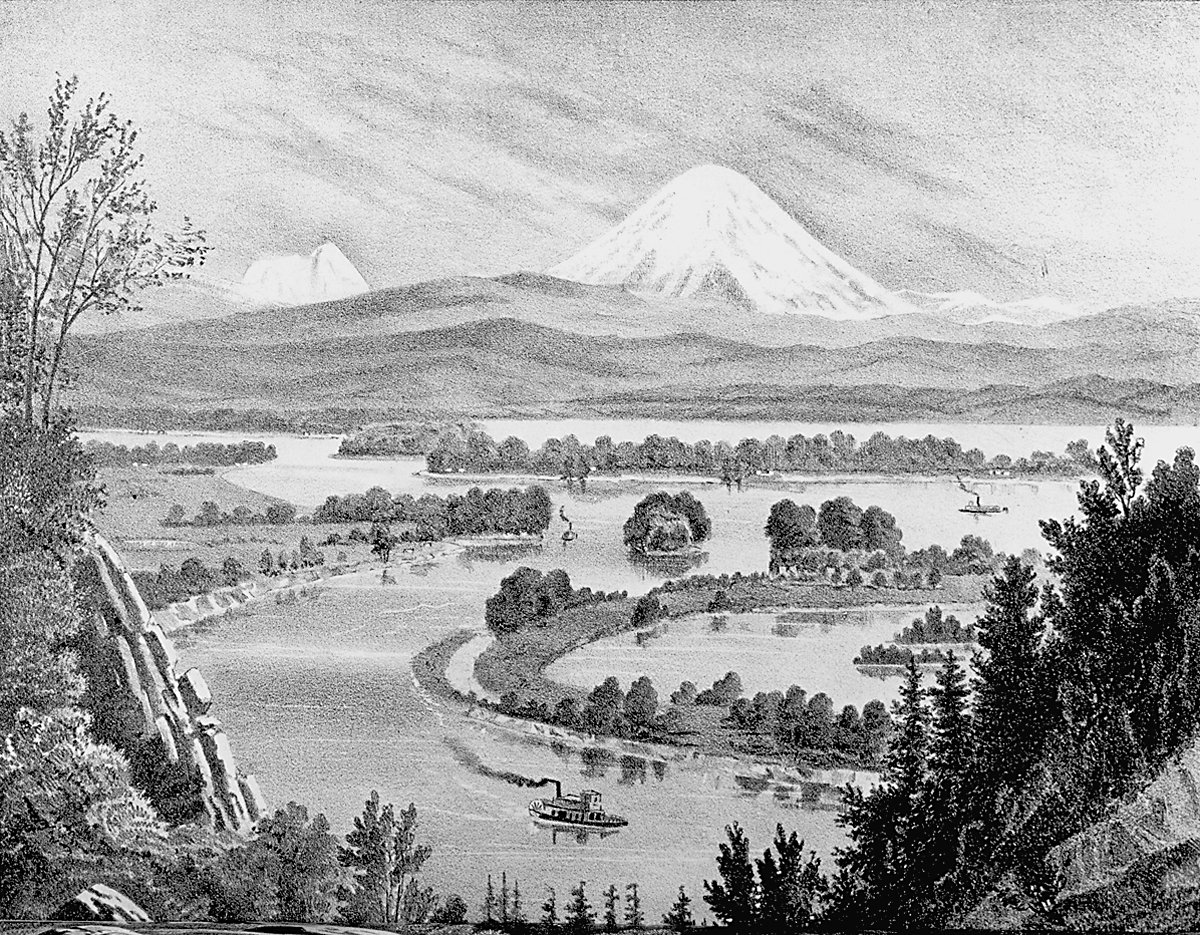

White settlers considered the lush Willamette Valley a prize, and the earliest immigrants sent word to friends and family and newspapers in the East that the rich soils and park-like settings were ideal for agriculture. The valley was an “Eden,” they reported, and beginning in the 1840s tens of thousands of Americans left the East and Midwest to travel west on the Oregon Trail.

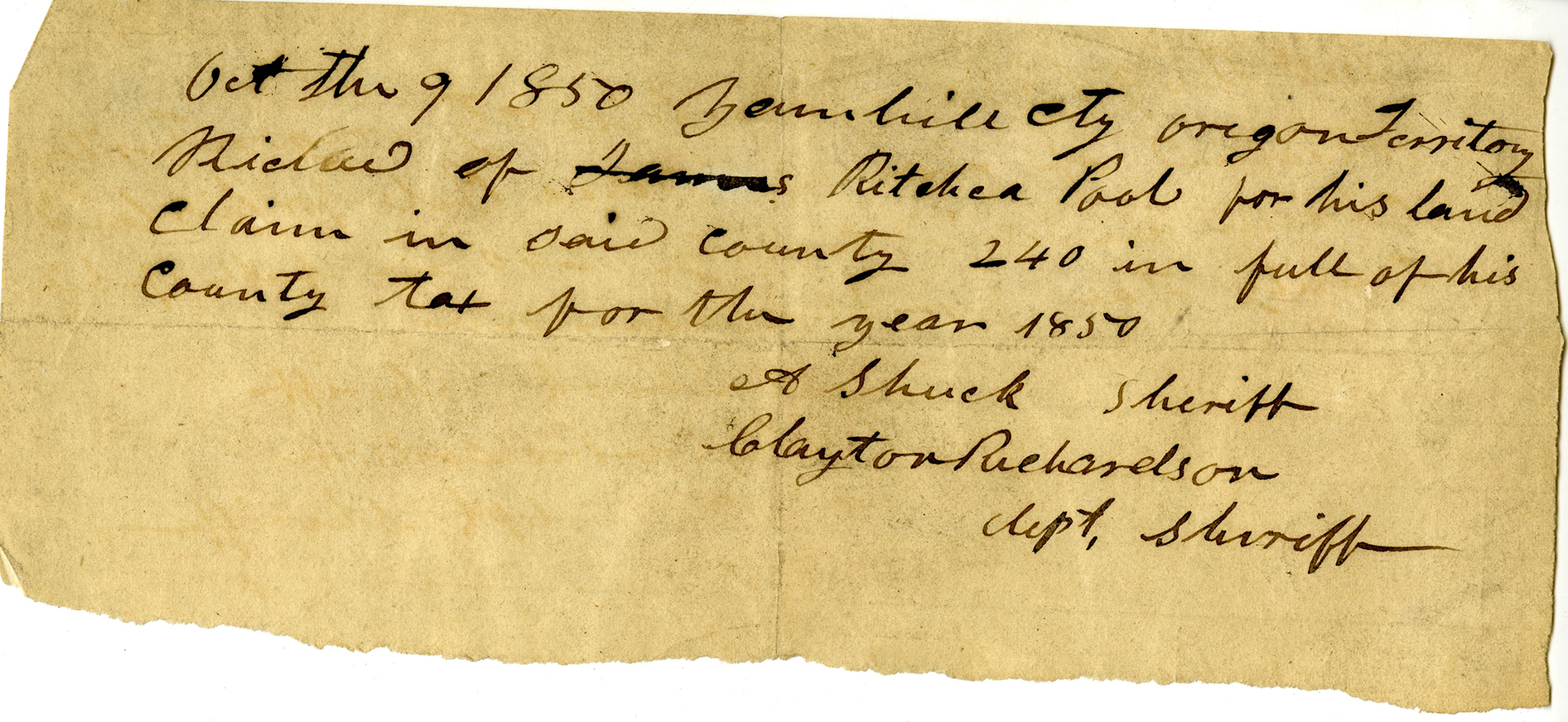

In 1846, the United States and Great Britain signed the Oregon Treaty, which gave the United States full claim to the lower Oregon Territory. In 1850, Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Act. The new law allowed settlers to keep their land claim made under the provisional government's land ordinance law and gave new settlers 320-acre (640-acre for married couples) claims once they entered Oregon Territory.

The government had yet to initiate a transfer of the aboriginal land claims of Native peoples. In 1850, President Zachary Taylor appointed Anson Dart as Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon Territory. Dart was charged with clearing the land titles for American settlement. He first negotiated individual treaties with Willamette Valley tribes in an effort to remove the tribes from the American settlements and move them to eastern Oregon. As inducements, he offered tribes money, food, and supplies so they would trade only with Americans and take up an agricultural way of life. An earlier trip by Dart to the Umatilla area and a meeting with the tribes there revealed that eastern Oregon Native peoples did not desire to have the western tribes removed there.

Dart signed treaties with the Kalapuya tribes in the Willamette Valley at Champoeg, Oregon Territory. There, he and his fellow commissioners negotiated for five days with tribal leaders. During the negotiations, other Kalapuya tribes joined with the powerful Santiam chiefs, Principal Chief Tiacan and Second Chief Alquema, who spoke strongly about what the land meant to their people. When the Indian agents suggested that their people move east of the Cascade Range, Tiacan stated: “Their hearts were upon that piece of land, and they didn’t wish to leave it.” Final inducements to move had no effect on the Kalapuya leader, and Alquema stated: “We don’t want any other piece of land as a reserve than that in the forks of the Santiam River. We do not wish to remove.” They would rather be shot, he said, than leave the land.

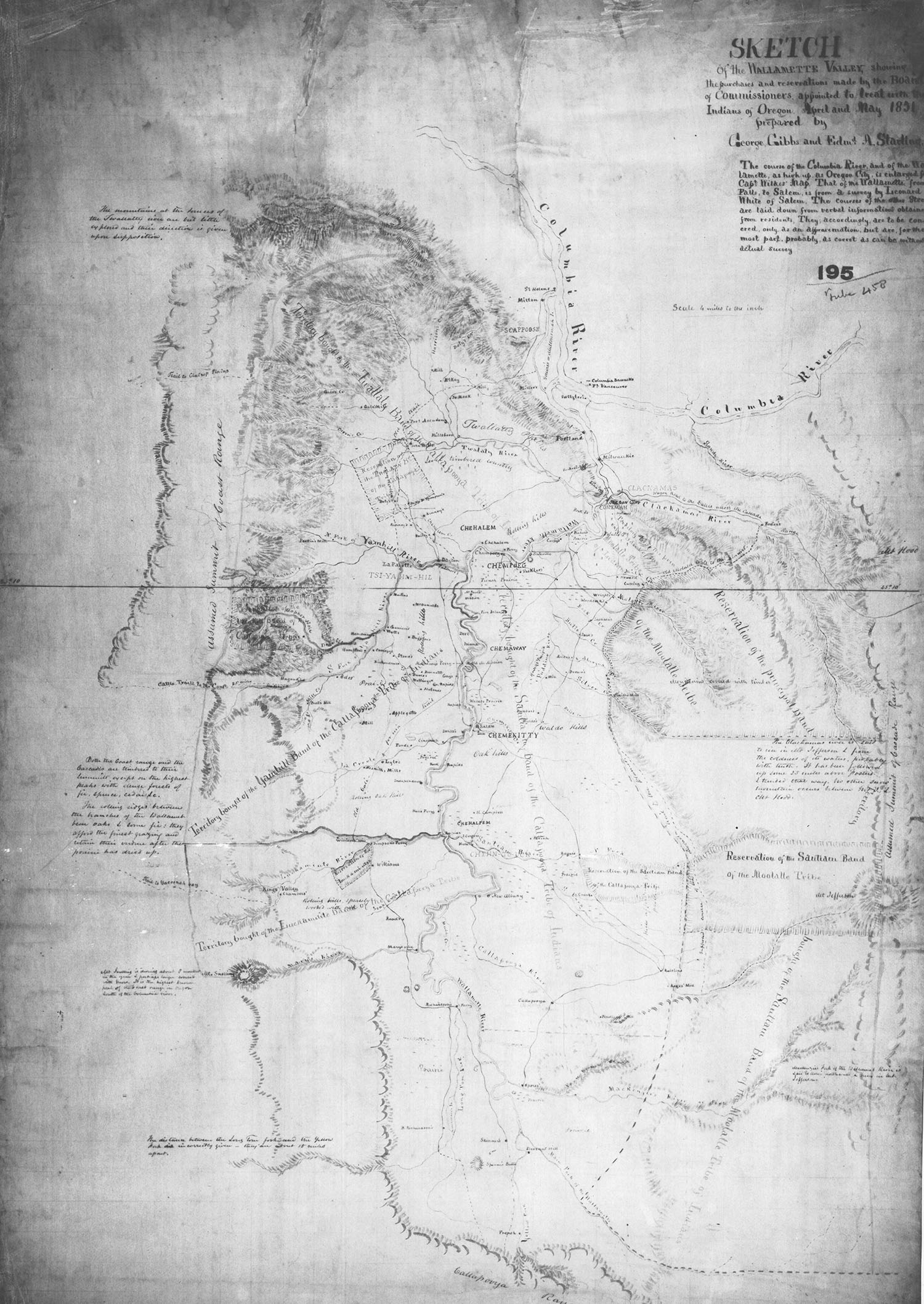

The Kalapuya tribes successfully defended their right to remain on their lands, and Dart was forced to include a small reservation within their homelands in all of their treaties. The treaties were with the Santiam (April 19, 1851), the Luckamiute (May 2, 1851), the Yamhill (May 2, 1851), the Tualatin (April 19, 1851), the Principal Band Molala (May 6, 1851), the Santiam Band Molala (May 7, 1851), and the Clackamas (November 6, 1851). A map drawn in 1851 by George Gibbs and Edwards Starling depicted where the temporary reservations were to be located in the Willamette Valley, once Congress ratified the treaties.

None of the eighteen treaties Dart sent to Washington, D.C., were ratified. American settlers in the Willamette Valley lodged complaints to Congress about the treaties. They did not wish to live among people who they considered savages and thieves. By accepting the reservation proposals of the tribes, Dart had failed to remove the tribes from western Oregon, and he was forced to resign.

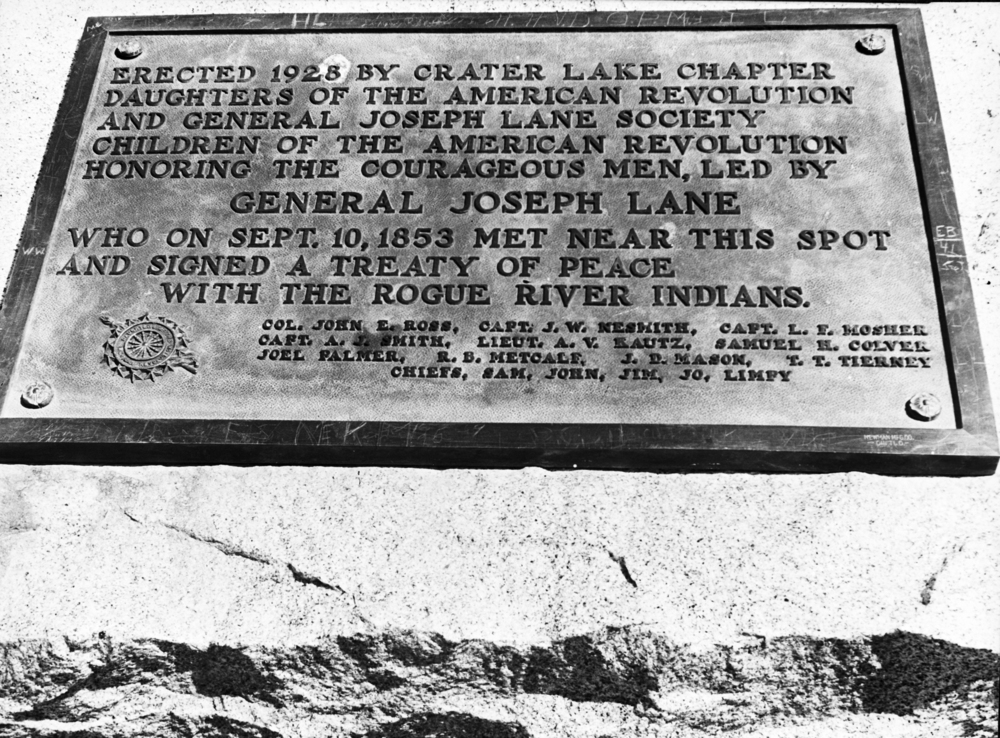

In 1853, President Franklin Pierce appointed Joel Palmer to be the Superintendent of Indian affairs for the Oregon Territory. Palmer had been a commissary-general of the Oregon Territorial militia. In response to a succession of conflicts between gold miners and what were known as the Rogue River tribes in 1853, he undertook a series of meetings with tribal leaders in southwestern Oregon to create a peace. “Rogue River tribes” was a local designation for a number of tribes from different language groups who lived in the Rogue River area: the Takelma, the Shasta, and many Athapaskan-speaking people generally called the Chasta Costa.

Palmer first worked to persuade the tribes to agree to remove to the east. When they refused, he adopted a new plan: the tribes who signed treaties would be removed to temporary reservations until the permanent reservation on the Oregon Coast was established. In western Oregon, Palmer negotiated nine treaties, seven of which were ratified by Congress.

The first treaty that Palmer negotiated in the Willamette Valley was with the Tualatin Kalapuya. While he had not yet been given the authority to negotiate a treaty with the Tualatins at Wapato Lake, he took a chance on March 25, 1854, when presented with an opportunity to negotiate with the Tualatin chiefs, who lived in the Tualatin Valley—one of the first places settled in the Willamette Valley. The treaty was never ratified because Palmer failed to get government permission to negotiate with the Tualatins. Similarly, in the summer of 1855, Palmer negotiated a treaty with many of the coastal tribes, a treaty that also was not ratified.

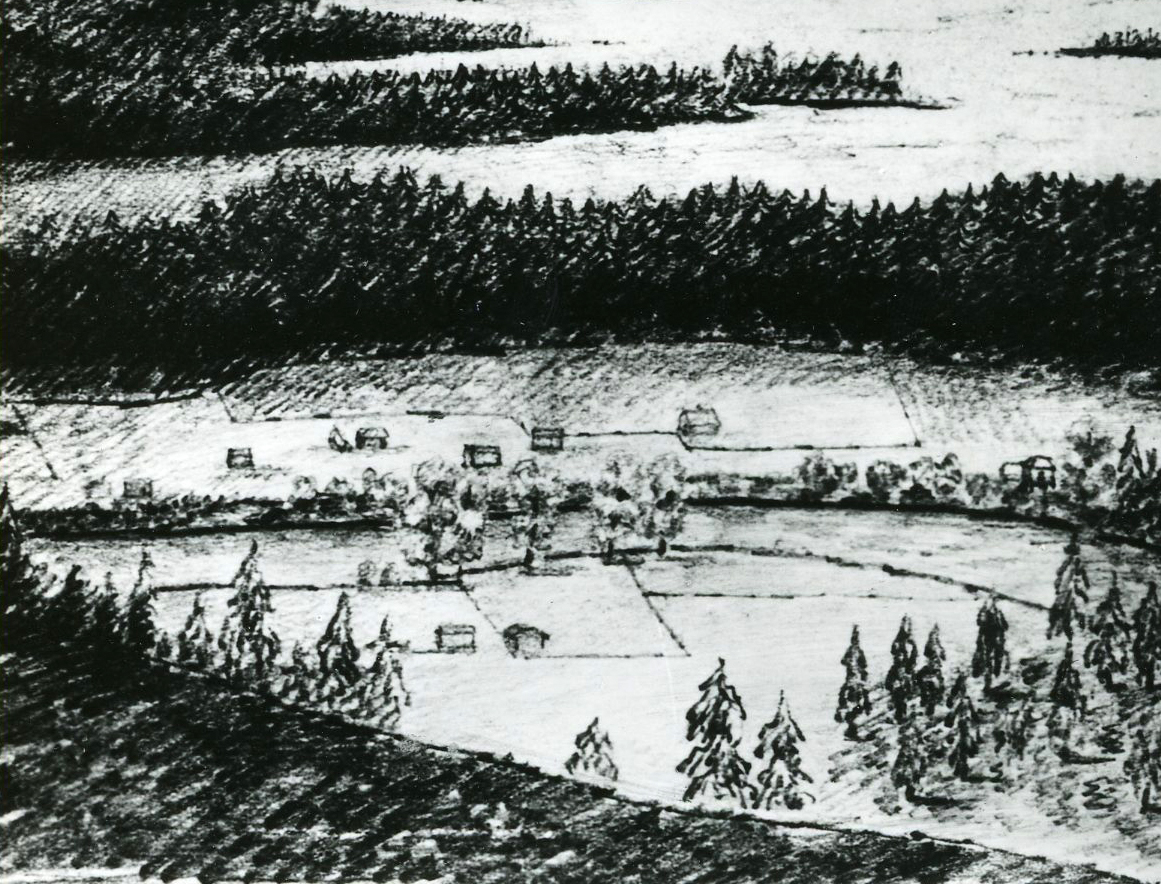

The treaty with the Kalapuya Etc.—also known as the Willamette Valley Treaty—was negotiated on January 22, 1855, at Dayton. Under the treaty, the tribes of the Willamette Valley chose to confederate. Those who agreed to the confederation were the majority of Kalapuyans, Santiam, Tualatin, Yamhill, Ahanchuyuk, Lackmiute, Mary’s River (Chelamela), Mohawk (Pee-you), Winfelly, and Calapooia. Also in agreement were the neighboring tribes on the edge of the valley—the Northern Molala, Santiam Molala, and Clackamas Chinook (Clowewalla, Watlala [Cascades], and Multnomah). Immediately following the treaty, Palmer established temporary reservations throughout the valley, at St. Helens, Spores ranch (Creswell), Corvallis, Molala, and Santiam and on Palmer’s property in Dayton. Settler farmers were appointed special Indian agents to feed and care for the people.

By December 1855, the war between Natives and whites in southwestern Oregon had become more violent, and Palmer was forced to remove the tribes to a permanent reservation. The Coast Reservation was not yet ready for habitation, so he worked with the U.S. Army at Fort Vancouver to purchase most of the land in what was known as the Grand Ronde Valley, at the western edge of the Willamette Valley. The small valley already had good supply roads into the Willamette Valley, along with farming facilities and crops in the ground.

In January 1856, Palmer had the Kalapuya tribal chiefs visit the proposed reservation to persuade them that it was good land, so they would carry this information to their people and effect the removal without threat or force. In late January, Palmer ordered the Indian agents to make plans to remove the tribes to Grand Ronde Agency.

From January to March 1856, the tribes from throughout western Oregon were marched to the Grand Ronde Agency, sometimes also called the Yamhill River Agency, in an event that the tribes call the “trail of tears.”

The tribes were settled on the new reservation in villages along the south fork of the Yamhill River. Some tribes had perhaps a few hundred people, while others had a few dozen. All of the Willamette Valley Kalapuya tribes remained at Grand Ronde once the Coast Reservation was opened in 1857. About two thirds of the Rogue River peoples were removed to the Siletz Agency. Palmer’s plan was to have the “warlike” tribes (those who had left Table Rock Reservation to fight) removed to Siletz and separated from the peaceful tribes (those had not left their assigned reservations) at Grand Ronde.

Between 1855 and 1875, the people at the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation received services and resources connected to the Kalapuya Etc. treaty. The treaty promised a permanent reservation, food and money, payment for a school for twenty years, opportunities to practice agriculture, and safety from attacks by white settlers. Under this arrangement, the tribes from throughout western Oregon lived on the reservation for a hundred years.

In 1954, Congress terminated the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation, the Siletz Indian reservation, and other fourth-sector (nonreservation) tribes in Oregon—sixty tribes in total—under the Western Oregon Indian Termination Act (PL 588). The act terminated all treaty rights and agreements through the U.S. government’s plenary powers—that is, the right to terminate any agreement with a foreign government.

In 1983, the Grand Ronde people successfully persuaded Congress and President Ronald Reagan to restore the Grand Ronde tribal government and its rights under the seven ratified treaties of western Oregon. In the twenty-first century, the Willamette Valley Kalapuyans, Molala, and Clackamas Chinook people remain members of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community.

-

![]()

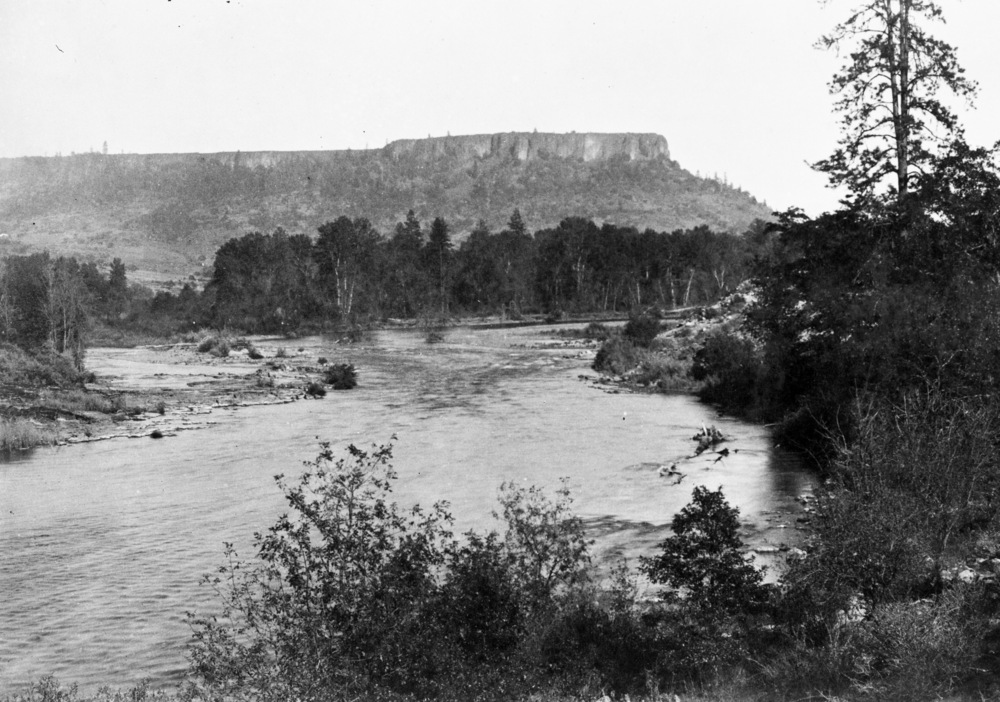

Table Rock, 1887.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 003842

-

![Hop pickers]()

-

![]()

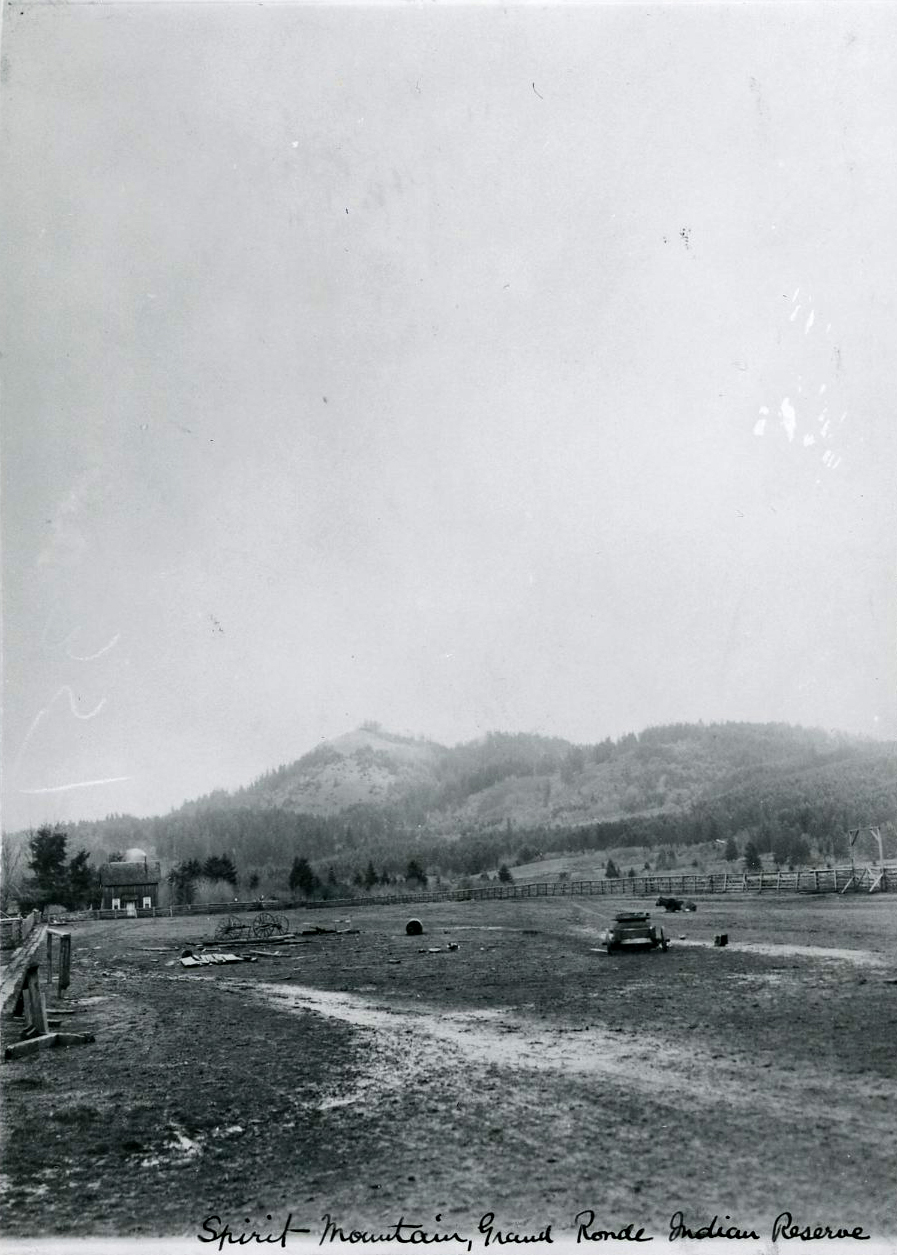

Spirit Mountain, 1904.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 019372

-

![]()

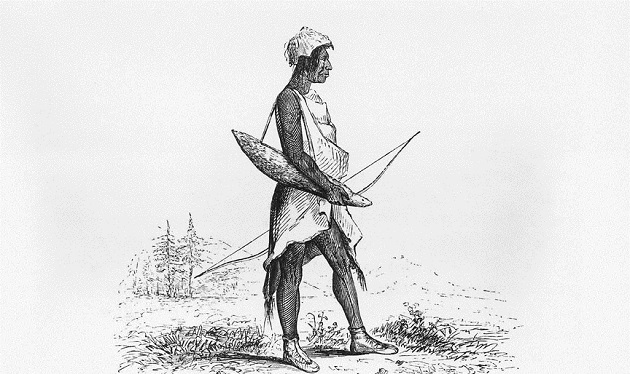

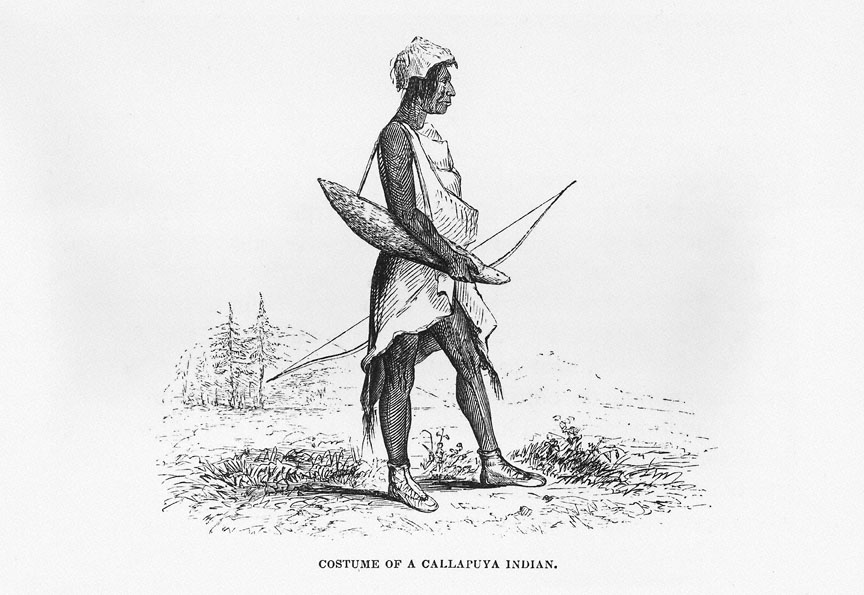

"Costume of a Callapuya Indian," 1841, by Alfred T. Agate.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 104921

-

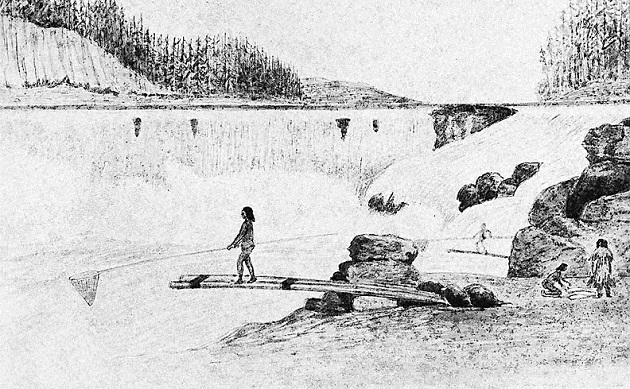

![Indians Fish at Willamette Falls, 1841. OrHi 46193]()

Indians Fish at Willamette Falls, 1841..

Indians Fish at Willamette Falls, 1841. OrHi 46193 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 46193

-

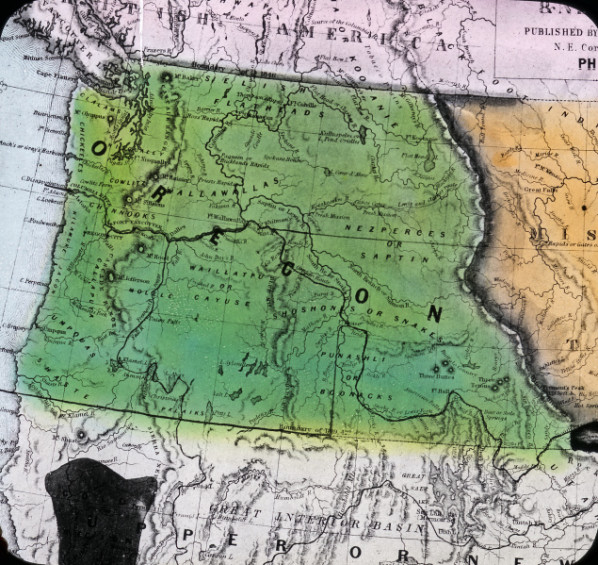

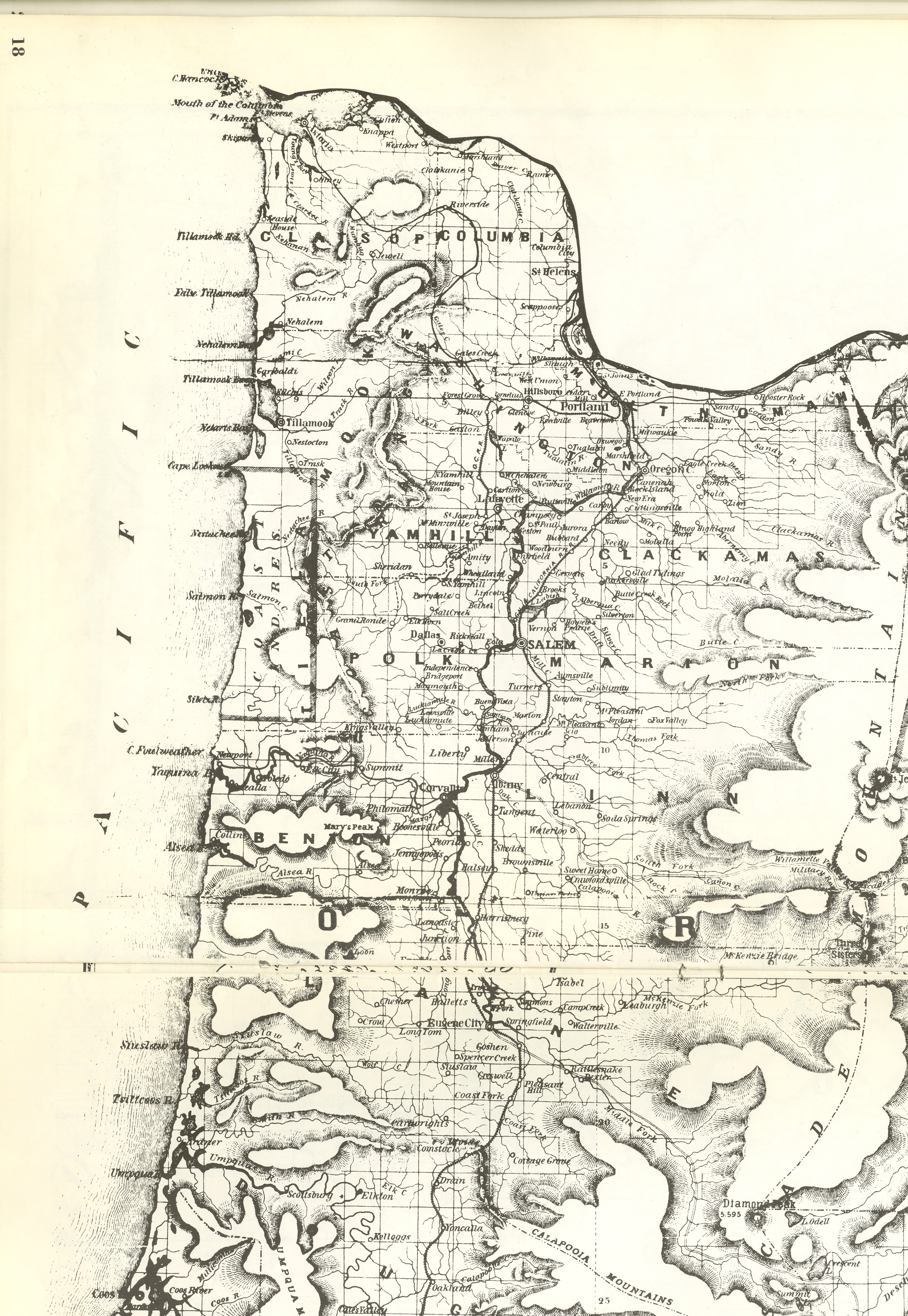

![Map of Oregon Territory, 1848]()

-

![]()

"The Kalapuya Communities" map, c. 1850.

Center for Columbia River History

-

![Map of land purchases and reservations negotiated by Board of Commissioners]()

Sketch of the Wallamette Valley, George Gibbs and Edmund Starling, 1851.

Map of land purchases and reservations negotiated by Board of Commissioners Courtesy Oregon State University Special Collections and Archives Research Center, Corvallis -

Siletz Agency, bb006476, 1.

U.S. Government buildings at Siletz Agency. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb006476

-

![Plaque commemorating treaty signing near Fort Lane, present day Camp White, Jackson County, Aug. 1942.]()

Rogue River Treaty plaque, bb004075.

Plaque commemorating treaty signing near Fort Lane, present day Camp White, Jackson County, Aug. 1942. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb004075

-

![]()

Closeup of the Grand Ronde Governance Building.

Courtesy Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community

Related Entries

-

![Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation]()

Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation

In September 1859, Joel Palmer, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs fo…

-

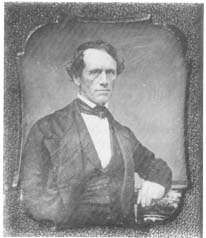

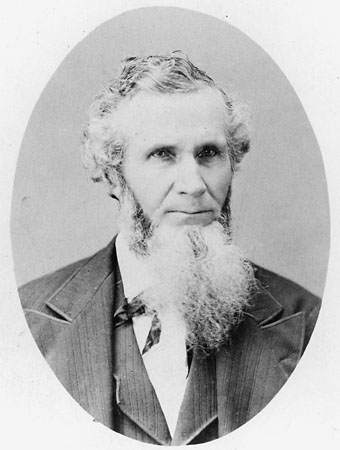

![Anson Dart (1797-1879)]()

Anson Dart (1797-1879)

In 1850, Anson Dart (1797-1879), of Wisconsin, was appointed as the fir…

-

Coast Indian Reservation

Beginning in 1853, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer negotia…

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![Council of Table Rock]()

Council of Table Rock

The 1853 Council of Table Rock negotiated a peace treaty between repres…

-

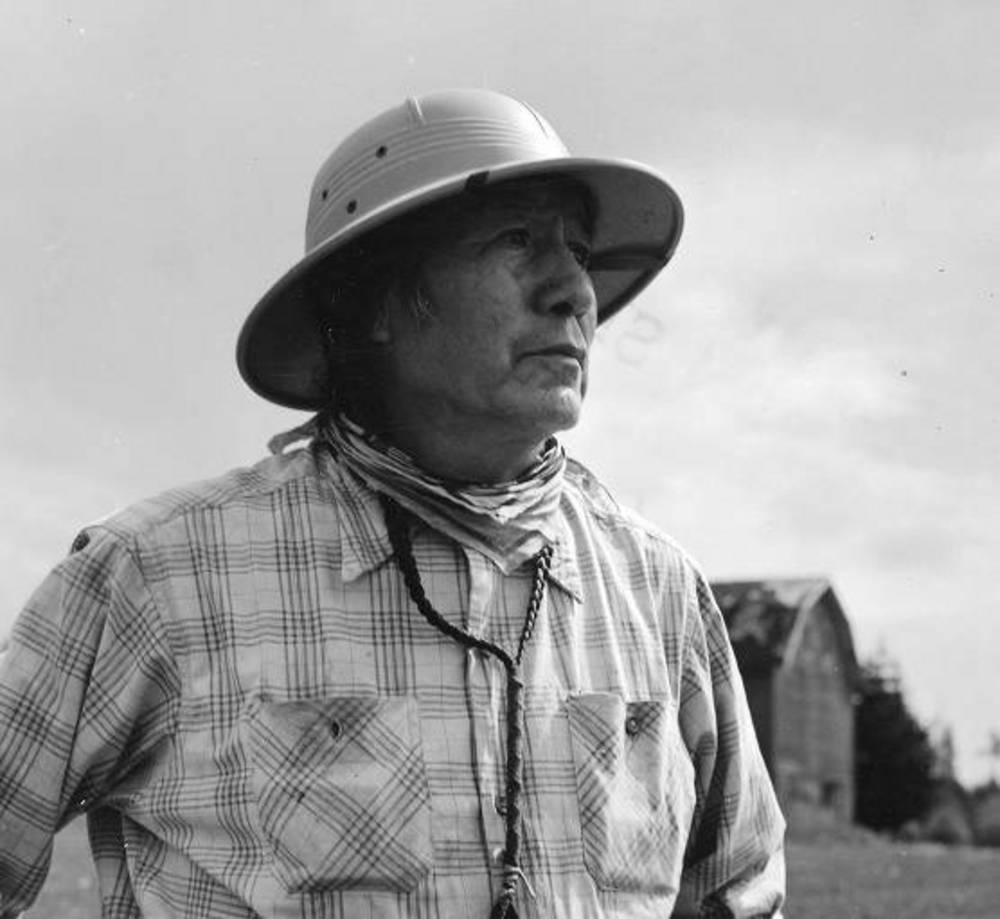

![Joel Palmer (1810-1881)]()

Joel Palmer (1810-1881)

Joel Palmer, who first saw the Oregon Country from a wagon in 1845, spe…

-

![Kalapuya Man Drawing]()

Kalapuya Man Drawing

Costume of a Callapuya Indian, also known as Kalapuya Man, is one of th…

-

![Kalapuya Treaty of 1855]()

Kalapuya Treaty of 1855

The treaty with the Confederated Bands of Kalapuya (1855) is the only r…

-

![Kalapuyan peoples]()

Kalapuyan peoples

The name Kalapuya (kǎlə poo´ yu), also appearing in the modern geograph…

-

![Kathryn Harrison (1924-2023)]()

Kathryn Harrison (1924-2023)

Kathryn Jones Harrison of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde was on…

-

![Native American Agricultural Labor]()

Native American Agricultural Labor

As early as the 1830s, when French Canadians associated with the Hudson…

-

![Native American Loggers in Oregon]()

Native American Loggers in Oregon

In pre-settlement times, native peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast …

-

![Oregon Donation Land Law]()

Oregon Donation Land Law

When Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Law in 1850, the legislat…

-

![Tualatin peoples]()

Tualatin peoples

Tualatin (properly pronounced 'twälə.tun in English) was the name of a …

-

Willamette River

The Willamette River and its extensive drainage basin lie in the greate…

-

![Willamette Valley]()

Willamette Valley

The Willamette Valley, bounded on the west by the Coast Range and on th…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaty Commission]()

Willamette Valley Treaty Commission

On June 5, 1850, An Act Authorizing the Negotiation of Treaties with th…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Deloria, Vine, Jr., and Raymond J. DeMaille. Documents of American Indian Diplomacy: Treaties, Agreements, and Conventions, 1775-1979. Norman: U. of Oklahoma Press, 1999.

Prucha, Francis Paul. American Indian Treaties: The History of a Political Anomaly. Berkeley: U. of California Press, 1997.