The rugged upland watershed of the Clackamas River lies within the Mount Hood National Forest. The river winds through the northern Oregon Cascades about thirty miles south of Mount Hood, reaching the Willamette Valley at Estacada and joining the Willamette River below Oregon City. During World War II, the U.S. Forest Service opened Clackamas timberlands to meet the country’s demand for lumber, and by the 1990s much of the forest had been logged. On March 30, 2009, President Barack Obama signed the Omnibus Public Land Management Act, which added more than two million acres of land in nine states to the National Wilderness National Preservation System, including 9,465 acres of remnant stands of old-growth Douglas-fir, western hemlock, grand fir, and western red cedar in the newly designated Clackamas Wilderness.

The five noncontiguous parcels that make up the Clackamas Wilderness are scattered along fifty miles of the Clackamas River and its tributaries: Big Bottom (1,263 acres), Clackamas Canyon (1,247 acres), Memaloose Lake (1,132 acres), Sisi Butte (3,243 acres), and the South Fork of the Clackamas (2,572 acres). Each unit features different characteristics of the pre-logging landscape. Big Bottom, located five miles upriver from the Collawash River confluence, is a riparian flatland with braided river channels, beaver dams, and cold-water fish habitat, as well as the largest western red cedars in Oregon, some measuring 12 feet in diameter. Looming nearly 3,000 feet above Big Bottom is Sisi Butte, a dormant shield volcano overlooking the Clackamas River headwaters. At an elevation of 5,520 feet, the butte is capped by a fire lookout tower, originally constructed in 1940 and rebuilt in 1997 (both the tower and access road were carved out of the 2009 protections). Far downriver, Clackamas Canyon, Memaloose Lake, and South Fork contain mossy, steep-sloped, old-growth forest with hillsides too unstable for logging roads.

What the units of the Clackamas Wilderness have in common is a lack of paved roads and a prohibition on future development, a standard established in the 1964 Wilderness Act. Because the parcels are so remote and widely spaced, however, it is preferable to use a car to visit the area. To get there, ironically, means driving along logging roads that were built originally to cut the forest down.

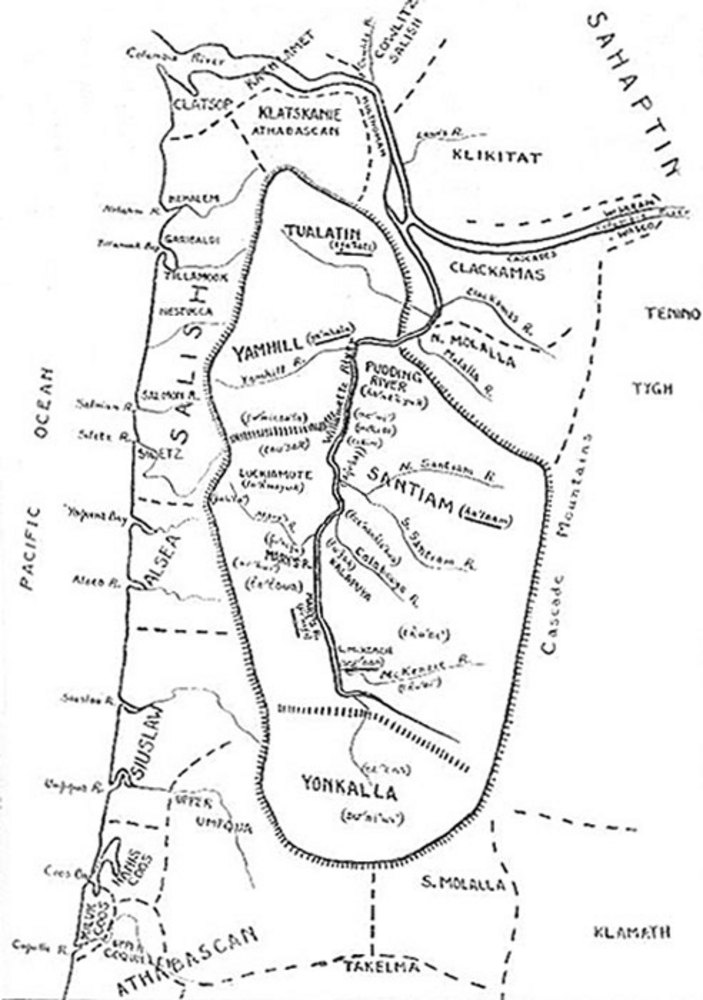

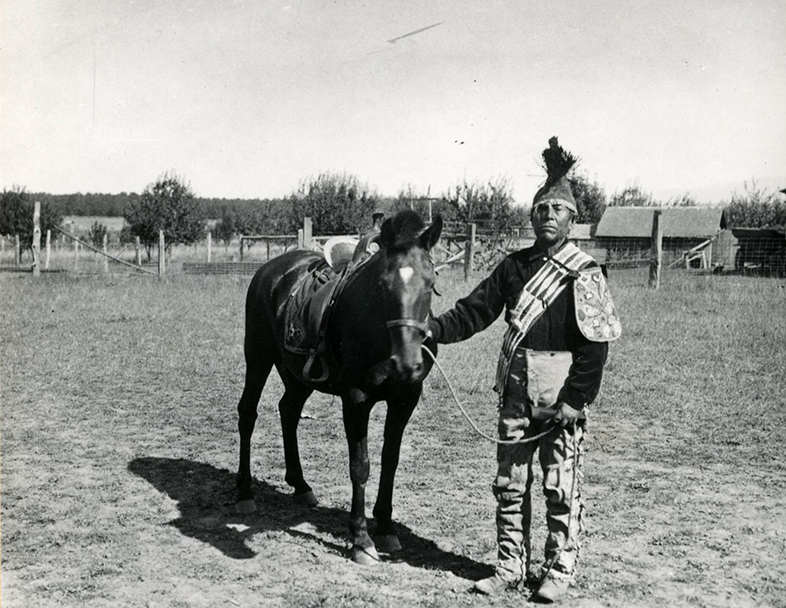

Indigenous people have lived in the northern Oregon Cascades for thousands of years.The river is named for the Clackamas people, who in the early nineteenth century numbered an estimated 1,800 people. They lived in villages on the lower Willamette and Clackamas Rivers, where they controlled access to fishing and trading at Willamette Falls. The Molalla people lived in the Clackamas River highlands, moving from the foothills into the Cascade Mountains during the warmer months. They managed the forest resources to increase the camas, serviceberries, and salmon, especially by using fire. Increasingly, the Forest Service has been learning from the Clackamas, Molalla, and other Native people how to manage the forests.

During the early to mid-nineteenth century, European fur traders and American resettlers began to colonize what non-Natives called the Oregon Country. In 1855, representatives of the Clackamas, Molalla, and other tribes signed the Kalapuya Treaty. The following winter, federal Indian agents removed them to the Grand Ronde Reservation, where many of their descendants live.

In 1893, President Grover Cleveland issued a proclamation establishing the Cascade Range Forest Reserve to protect timber and water resources on 4.5 million acres of land in Oregon, including what is now the Clackamas Wilderness. In 1908, Congress divided the reserve into smaller units, and the upper Clackamas watershed became part of the Oregon National Forest, which was renamed the Mount Hood National Forest in 1924.

In 1928, the upper Clackamas watershed was in one of the largest roadless areas in the United States, with nearly a quarter million acres of unbroken forest from Mount Jefferson to the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. Beginning during World War I and accelerating under the New Deal, the Forest Service and Civilian Conservation Corps constructed fire lookout towers. Structures went up on Tumala Mountain (1916), High Rock (1925), Indian Ridge (1932), Fish Creek Mountain (1933), Oak Grove Butte (1933), Peavine Mountain (1933), Hillockburn (1936), Eagle Creek (1937), Bedford Point (1939), Sisi Butte (1940), and Bull of the Woods (1942). To service the growing forest surveillance infrastructure, which included guard stations, ranger cabins, and often telecommunications equipment, the Forest Service built truck roads. Those rudimentary roads, such as Abbott Road (NF-4610) northeast of Estacada, expanded existing foot trails to ridgelines to provide access for official vehicles.

As the United States entered World War II, public access to the upper Clackamas remained limited. Conditions changed rapidly in 1942 when demand for softwood lumber skyrocketed to supply the Allied Forces with products that ranged from crates to caskets. Amplified by a postwar housing boom, the wartime need to “get the cut out” (a phrase commonly used to refer to harvesting timber) prompted large-scale logging on federal lands throughout the Pacific Northwest. The Forest Service prioritized the upper Clackamas, which still had potentially billions of board-feet of uncut timber. Loggers transformed the forest over the next half-century, removing much of the old-growth Douglas-fir and leaving access roads on nearly every tributary. At its height, the Clackamas River Road (after 1961, Oregon Highway 224) was one of the busiest logging corridors in the country. In 1959, one Forest Service official estimated, perhaps with some exaggeration, that logging trucks were “roaring down the road at a rate of one a minute.”

The 1984 Oregon Wilderness Act, introduced by Representative James Weaver (D-Ore.), established twenty-two new wilderness areas and enlarged seven others on Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management land. Included in the list of new entries to the National Wilderness Preservation System was Bull of the Woods Wilderness, the first from the upper Clackamas. For the time being, the pockets of forest that would become the Clackamas Wilderness were left open to logging because they were small, scattered, and relatively unspectacular.

Interest in protecting more of the Clackamas drainage came together in the early 2000s. In 2004, Andy Kerr, an activist with the Oregon Natural Resources Council (now called Oregon Wild), described a proposal for Clackamas Wilderness and ten other multi-unit designations in the Cascades in Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness.

In 2007, Senator Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) introduced the Lewis and Clark Mount Hood Wilderness Act, which included five roadless areas that made up the 9,470-acre Clackamas Wilderness. The proposal found success when conservation-minded members of Congress bundled together public lands legislation from multiple states in the Omnibus Public Land Management Act of 2009.

In early September 2020, the Riverside Fire burned over the three lower units of the Clackamas Wilderness: Clackamas Canyon, Memaloose Lake, and South Fork. The 138,000-acre wildfire devastated much of the second- and old-growth forest upriver. The legal protections codified in the 2009 Act mandate that the surviving trees be allowed to mature to old-growth.

That these fragments of ancient forest remain in the Clackamas Wilderness are the result, in part, of over a century of conservation legislation, informed by an understanding of the environmental and biological importance of maintaining wilderness as a place “where man is a visitor that does not remain.”

-

![]()

Dorothy Lynch, Sisi Butte Lookout Tower, 1951.

U.S. Forest Service -

![]()

Clackamas Wilderness map.

U.S. Forest Service -

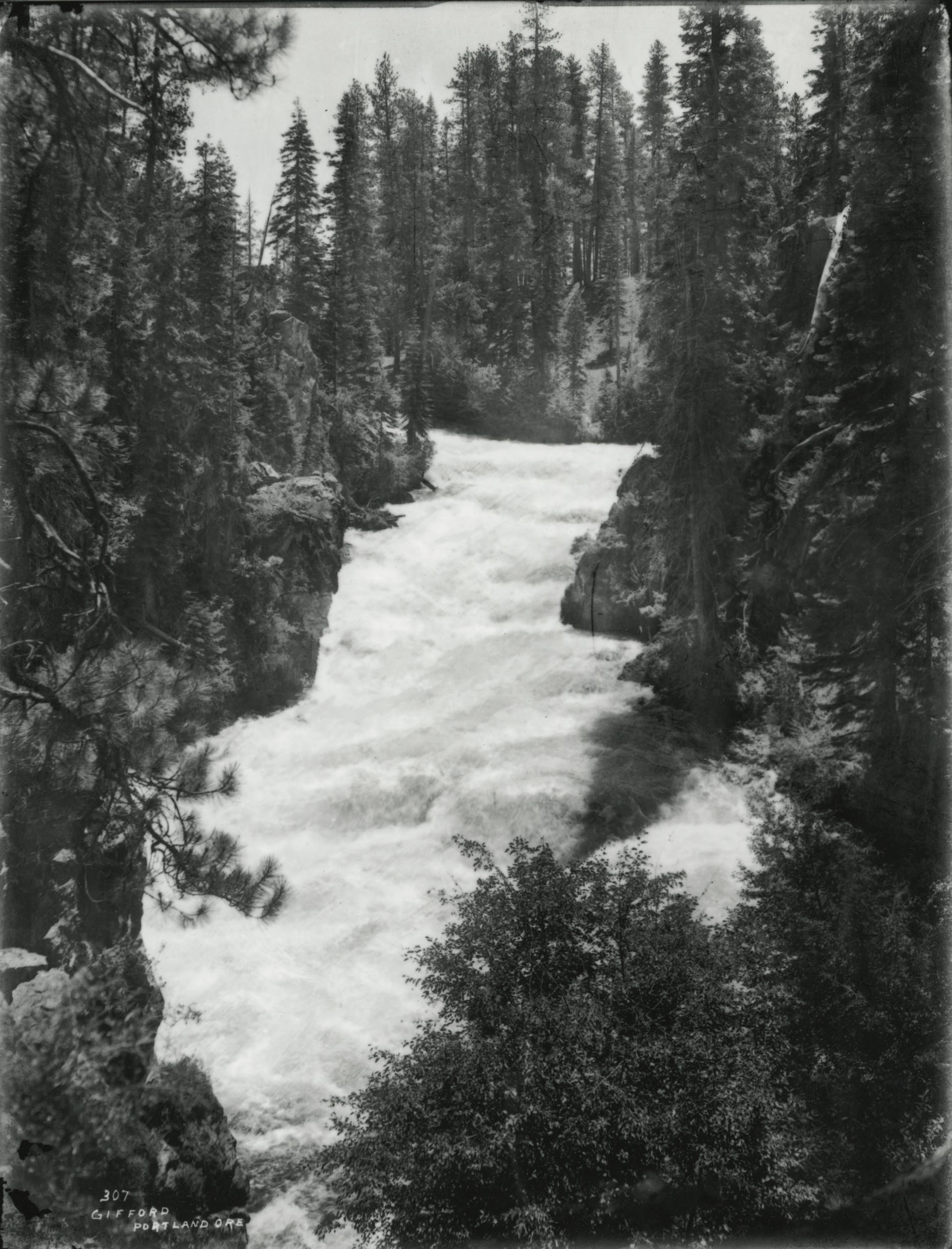

![]()

Clackamas Wilderness.

U.S. Forest Service -

![]()

Clackamas River entering Clackamas Wilderness, 2016.

U.S. Forest Service -

![]()

Sisi Butte lookout.

National Museum of Forest Service History -

![]()

Memaloose Creek Falls, after Riverside Fire, 2021.

U.S. Forest Service -

![Estacada was a mill town for logging in the Clackamas River watershed.]()

Related Entries

-

![Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument]()

Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument

“With towering fir forests, sunlit oak groves, wildflower-strewn meadow…

-

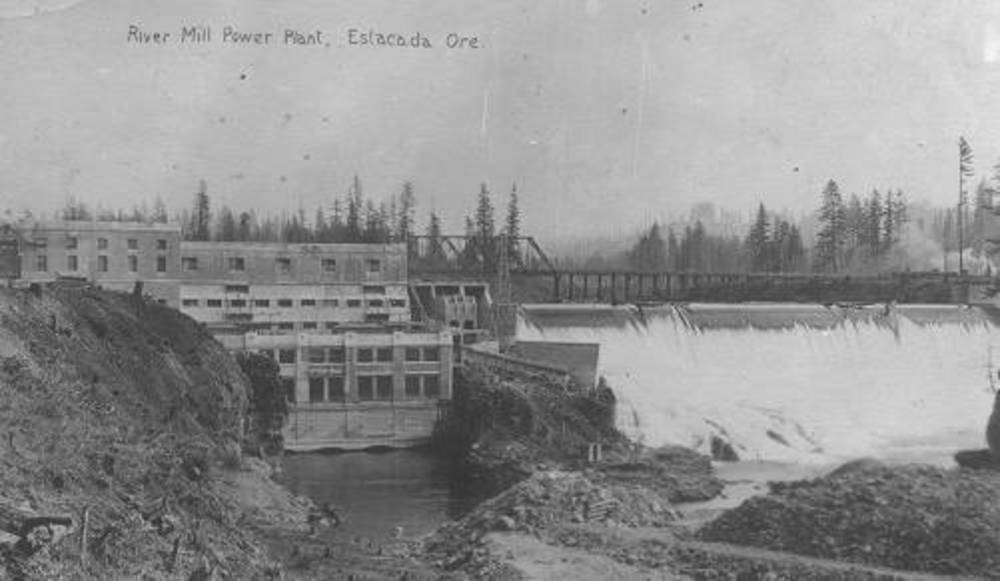

![Clackamas Hydroelectric Project]()

Clackamas Hydroelectric Project

The Clackamas River Hydroelectric Project is a series of four powerhous…

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

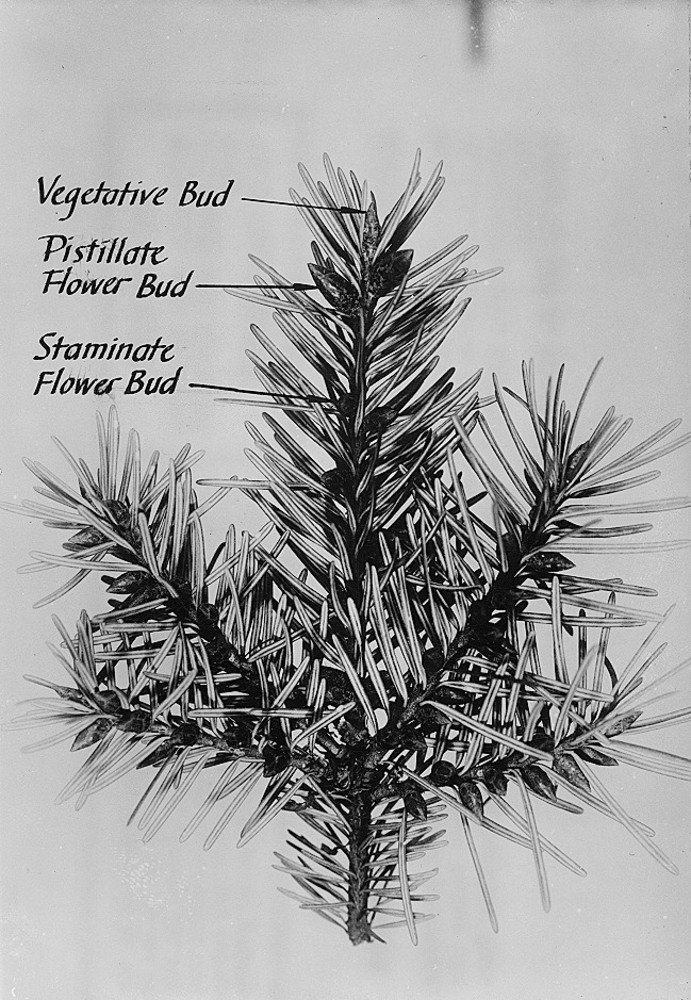

![Douglas-fir]()

Douglas-fir

Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), perhaps the most common tree in Or…

-

![Estacada]()

Estacada

Estacada (pop. 3,400 in 2018) sits on the right bank of the Clackamas R…

-

![Kalapuya Treaty of 1855]()

Kalapuya Treaty of 1855

The treaty with the Confederated Bands of Kalapuya (1855) is the only r…

-

![Kalmiopsis Wilderness]()

Kalmiopsis Wilderness

The 179,850-acre Kalmiopsis Wilderness, located in southwestern Oregon …

-

![Molalla Peoples]()

Molalla Peoples

The name Molalla ([moˈlɑlə, ˈmolɑlə], usually spelled Molala by anthrop…

-

![National Wild and Scenic Rivers in Oregon]()

National Wild and Scenic Rivers in Oregon

The world's first and most extensive system of protected rivers began w…

-

![Oregon Natural Resources Council v. John R. Block]()

Oregon Natural Resources Council v. John R. Block

In December 1983, the Oregon Natural Resources Council (now called Oreg…

-

![Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness]()

Salmon-Huckleberry Wilderness

One of Oregon’s forty-seven federally established wilderness areas, the…

-

![Three Arch Rocks National Wildlife Refuge and Wilderness]()

Three Arch Rocks National Wildlife Refuge and Wilderness

At fifteen acres, Three Arch Rocks lays claim to being one of the small…

-

Three Sisters Wilderness

The Three Sisters Wilderness area in the central Cascade Mountains has …

-

![Timber Industry]()

Timber Industry

Since the 1880s, long before the mythical Paul Bunyan roamed the Northw…

-

Willamette River

The Willamette River and its extensive drainage basin lie in the greate…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

“Clackamas Wilderness.” U.S. Forest Service. https://www.fs.usda.gov/recarea/mthood/recarea/?recid=79436.

Kerr, Andy. Oregon Wild: Endangered Forest Wilderness. Portland: Oregon Natural Resources Council, 2004.

Rose, Taylor. “The ‘Opening of the Clackamas’: Log Trucks, Access Roads, and Multiple-Use Infrastructure in Oregon’s National Forests.” Western Historical Quarterly 53.2 (Summer 2022): 167–93.

Williams, Gerald W. The U.S. Forest Service in the Pacific Northwest: A History. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2009.

Hirt, Paul W. A Conspiracy of Optimism: Management of the National Forests Since World War Two. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

Turner, James Morton. The Promise of Wilderness: American Environmental Politics since 1964. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012.

Spores, Ronald. “Too Small a Place: The Removal of the Willamette Valley Indians, 1850-1856.” American Indian Quarterly 17.2 (1993): 171–91.

Ruby, Robert H., and John H. Brown. A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992.

Beckham, Stephen Dow, ed. Oregon Indians: Voices from Two Centuries. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2006.

“Our Story.” Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde.

“Riverside Fire.” Mt. Hood National Forest. ArcGIS StoryMaps, July 29, 2021.

"Recreation Resources of Federal Lands: Report of the Joint Committee of Recreational Survey of Federal Lands." American Forestry Association and National Parks Association. Washington, D.C.: National Conference on Outdoor Recreation, 1918.

Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984. H.R. 1149, 98th Congress (1984)

Omnibus Public Land Management Act. Public Law No: 111-11, 111th Congress (2009).