The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confederation of over twenty-seven tribes and bands from western Oregon, southern Washington, and northern California. The tribes were removed to the Grand Ronde Reservation in 1856 by the U.S. government in order to free the land for American pioneer settlement and to alleviate the mounting conflicts among the tribes and settlers, miners, and ranchers. The community lived on the reservation until 1954, when Congress passed the Western Oregon Indian Termination Act (PL 588). The act took effect in 1956, when the treaties and the reservation were terminated. The tribe existed as a nonrecognized government for twenty-seven years until Congress passed the Grand Ronde Restoration Act on November 22, 1983.

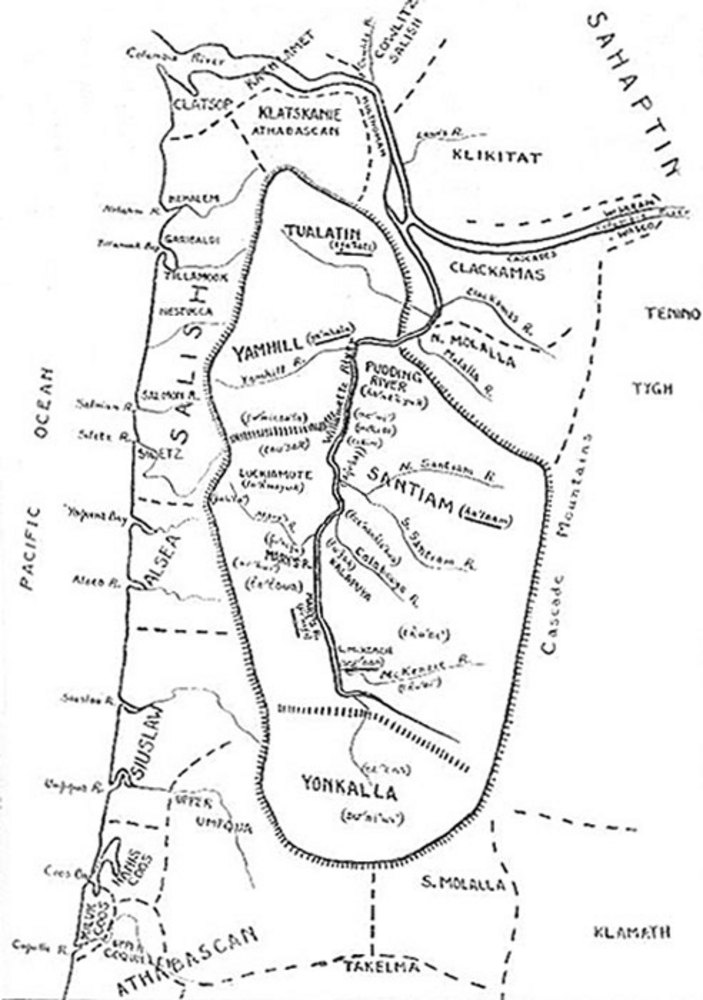

Before the 1850s and removal to the reservation, there were about sixty different tribes from six different language groups in western Oregon. The U.S. military forced at least twenty-seven of those tribes, about 2,000 people, to resettle at the Grand Ronde Agency in the southern Yamhill valley in 1856. The tribes were the Kalapuyans, which included the Santiam, Tualatin, Marys River, Yamhill, Yoncalla, Winefella, Mohawk, and Long Tom; the Chinookans, which included the Clackamas Oregon City, Watlala, Multnomah, and Cascades; the Molala Northern, Santiam, and Southern; the southwestern Oregon tribes, which included the Rogue River, Cow Creek Umpqua, Takelma, and Chastacosta; and a few people of other tribes like the Shasta, Klamath, and Klickitat. The name Rogue River refers to a number of tribes in the Rogue River area, mainly the Dakubetede and Chastacosta (Athabaskan), the Shasta (Hokan), the Takelmas, and some neighboring tribes or bands.

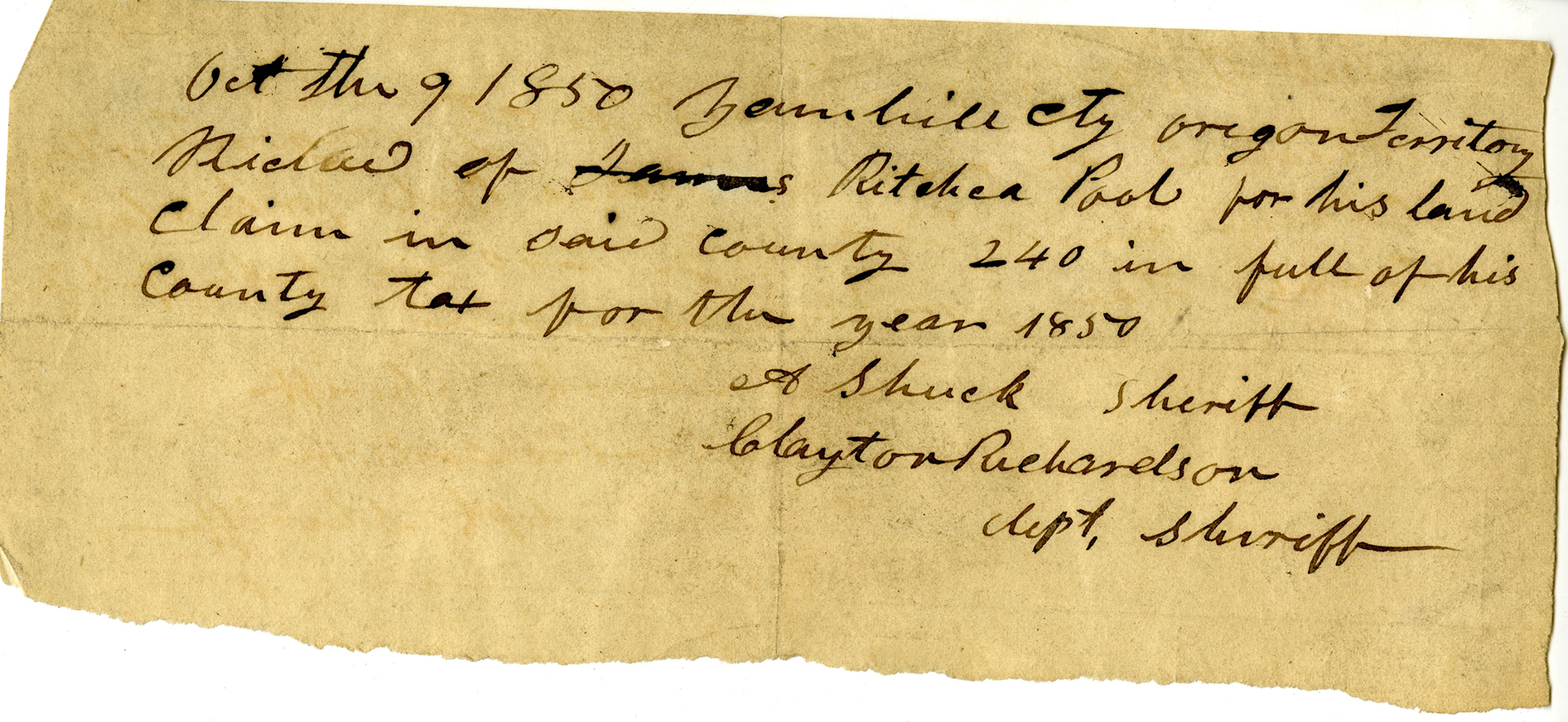

Most tribes were party to seven treaties ratified by the U.S. Congress, and members of those tribes were removed to reservations in 1856. These ratified treaties are with the Rogue Rivers (1853, 1854), the Cow Creek Umpqua Band (1853), the Chasta Costa (1854), the Yoncalla and Molala (1854), the Kalapuya etc. (1855), and the Molala (1855).

Even though they did not have a ratified treaty, members of other tribes joined the Grand Ronde Reservation between the 1860s and the 1890s, including members of the Tillamookan tribes, the Nehalem, Salmon River, Nestucca, and Tillamook. At removal, some tribes consisted of fewer than a dozen individuals, while most had thirty or more members. The most populous individual tribes at Grand Ronde were the Kalapuyas tribes and bands—each had several hundred members.

The Grand Ronde Reservation of 1856 consisted of 61,440 acres of former Donation Land Claim allotments that had been settled by pioneer farmers. The U.S. Army had purchased the land from the farmers to create a temporary reservation away from most white settlements in Oregon. Joel Palmer, superintendent of Indian Affairs for Oregon, worked with the army to remove all tribes in western Oregon from regions of increasing attacks on tribal settlements by members of the Oregon volunteer militias.

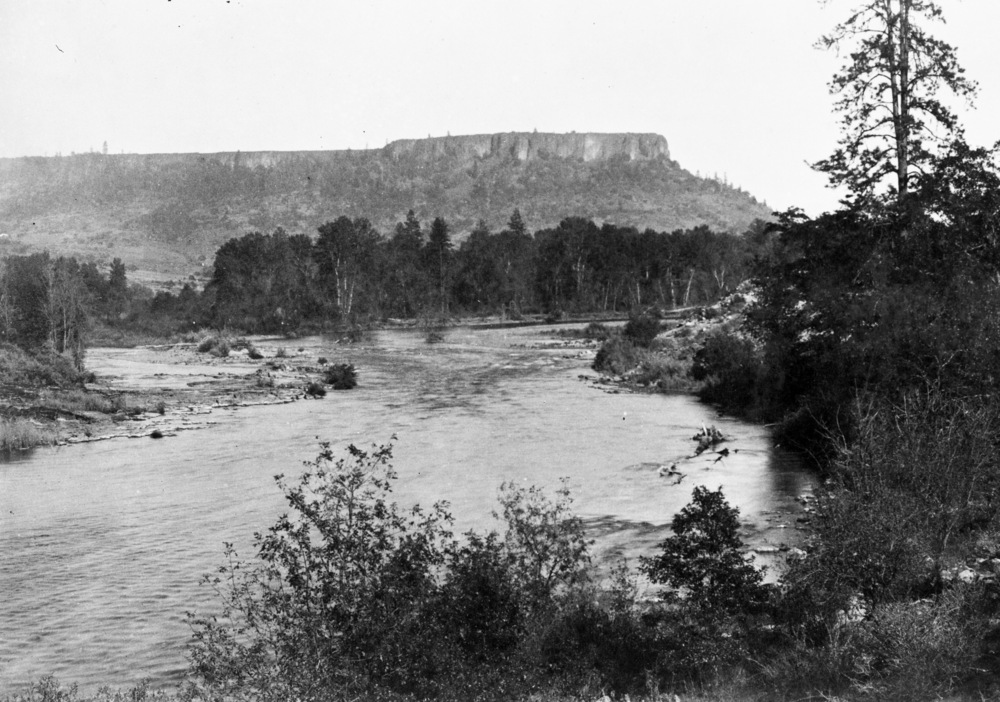

The Grand Ronde Valley, along the South Yamhill River in a remote part of the mid Willamette Valley, was selected for the reservation because its location against the Coast Range could be easily defended from settler attacks. In addition, a narrow access road to the east could be defended by a high hill, which made it easier to keep people on the reservation and to keep unwelcome visitors out. Fort Yamhill Blockhouse was situated at the top of Fort Hill, and the Grand Ronde Agency was eventually situated at the crossroads of Highway 18 and Grand Ronde Road, known as Old Grand Ronde.

The U.S. Army stationed a succession of attachments of dragoons and infantry at the fort from 1856 to 1866, including the 9th Oregon Mounted Volunteers, the 4th U.S. Infantry, the 1st U.S. Dragoons, the 9th U.S. Infantry, the 4th California Volunteer Infantry, the 1st Washington Volunteer Infantry, and the 1st Oregon Volunteer Infantry. The fort was abandoned in 1866 amid pressures during the Civil War when federal troops left to fight and the tribes at the reservation were deemed nonthreatening.In the first few years of the twentieth century, the blockhouse was moved to a city park in Dayton. The Fort Hill site was bought by the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department in 1988 and opened as Fort Yamhill State Park in 2006.

President James Buchanan’s executive order of June 30, 1857, officially established the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation. In 1857, about two-thirds of the Rogue River Indians moved to the newly built Siletz Agency to join the southern Oregon and coastal tribes on the Coast Reservation, which had been established in 1855.

At first, the resettled tribes at Grand Ronde did not integrate with each other and created separate settlements along the Yamhill River. Indian agency policies and stipulations in the treaties forced the tribes to alter their traditional lifeways, and they had to depend on the federal government for food and supplies and for social, medical, and educational services. The agency built several schools at Grand Ronde as part of the treaty stipulations, and in the 1860s the government designated the Catholic Church to administer the education of tribal children. Father Adrian Croquet (also spelled Crocket) of Belgium ran the on-reservation boarding school and provided ministerial services to the tribes for over forty years.

The small number of tribal people who removed to Grand Ronde is attributed to the history of disease among Natives and their conflicts with settlers. European and American trading ships had brought diseases such as smallpox and malaria to the coastal and Columbia River tribes. Beginning in the 1780s and subsequently during the fur trade era (1811-1840s), an estimated 97 percent of tribal populations died from introduced diseases. American explorers like David Douglas recorded seeing villages in western Oregon with no inhabitants, possibly because of diseases.

From the 1840s to 1860, additional population declines resulted from skirmishes and wars with white settlers and miners. The governments of the territories of California and Oregon widely supported volunteer militias, who sometimes exterminated entire villages in northern California and southern Oregon. After removal to reservations, the stresses of cultural change and the abuses of the reservation system forced a further population decline. By 1900, there were fewer than 400 Native people at the Grand Ronde Reservation, a dramatic decline from the estimated 20,000 people who had lived in the Willamette Valley before American encroachment, and an estimated 80,000-120,000 who inhabited all of western Oregon.

Between the 1850s and the 1890s, life on reservations in Oregon was difficult and living conditions were harsh. A few years after establishing the reservation, the federal government’s funding for services guaranteed through the treaties began to decline. Native peoples were federally managed and were not allowed to leave without a pass or to return if they left without approval. The inhabitants had to depend on the federal government for nearly every resource.

Federal funding was slow to arrive each year, forcing Indian agents to make repeated requests for money for medical services and for basic resources like blankets, clothing, medical supplies, and food. There was also a lack of necessary equipment, such as farm implements, and clothing and food shortages were common. Services to tribal members suffered as well. Although a doctor was assigned to the reservation, many medicines were as much as twenty years old, and people had to travel to towns in the Willamette Valley to find effective medicine for their illnesses.

Many people chose to leave the reservation temporarily, legally or illegally, to work as laborers during harvest season in the Willamette Valley. Native families harvested hops, beans, and berries during the summer months while their wheat or hay fields were maturing on the reservation. Men took jobs logging timber, spending months and years away from their families and sending checks back home to augment family income. This practice of seasonal population movement continued into the twentieth century and ended for most tribal people with termination. Some tribal members continue the traditions of fruit, berry, and vegetable farming to this day.

On the reservation, individuals developed cottage industries by harvesting products of the neighboring forest, such as chittam bark (Cascara sagrada, Rhamnus purshiana), mushrooms, and moss. Many women were practiced weavers, and they made baskets for sale to people in neighboring towns for a few dollars apiece. Baskets were made most commonly from willow (Salix lasiandra), hazel (Corylus avellana), and juncus (Juncus effusus), and the double-handled style of open-weave baskets was common. Women harvested the materials for weaving from reservation timberlands and seasoned them for a year. They traveled to Dallas, Sheridan, and McMinnville to sell their baskets at houses where they knew people were interested in collecting Native arts and crafts. These baskets were sold in Portland as “Grand Ronde Baskets.” Many of the baskets are now making their way back to the tribe.

The reservation environment kept the inhabitants in a state of stress over their safety and security. P.B. Sinnott, the Indian agent at Grand Ronde Reservation in 1877, described it this way: “The Indians of this agency are kept in a state of constant uneasiness and insecurity by reports of whites with whom they come in contact to the effect that they are soon to be removed from their present homes, and that the deeds to their lands are valueless, and may at any time be annulled or canceled.”

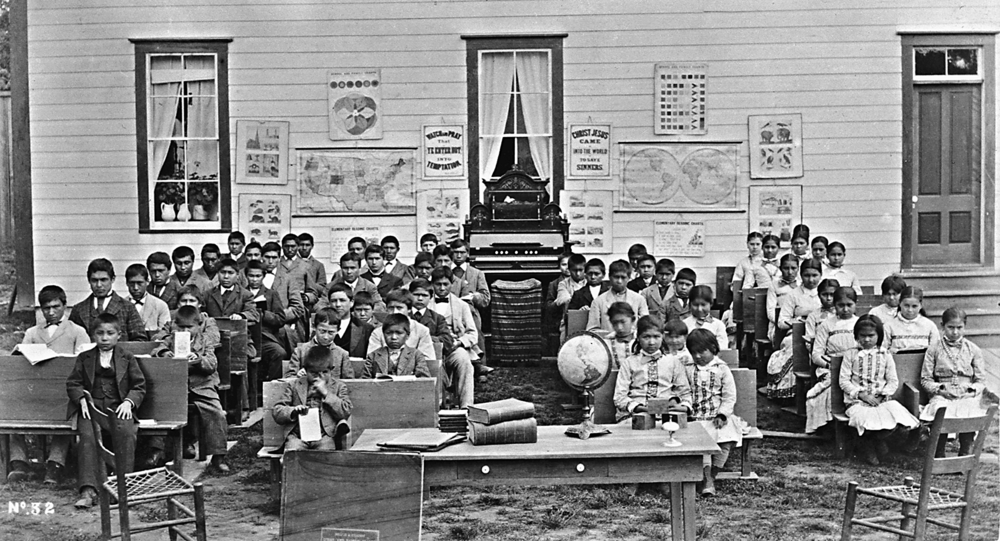

The government’s policy toward the tribes was assimilation. Educational services were intended to teach Native children how to be white Americans and to discourage traditional lifeways, languages, and modes of dress. By the 1880s, many children were being taken into boarding schools, where intensive assimilation education was practiced.

In 1887, Congress passed the Dawes Severalty Act, which gave every tribal member, with half Indian blood or more, an allotment of land. The act was intended to further assimilate the tribes and remove surplus lands from the reservation. In 1891, 270 tribal members at Grand Ronde Indian Reservation, mainly men and unmarried women, gained allotments. By July 1901, 33,468 acres were allotted to 274 Indians, leaving 25,791 acres unallotted and 440 acres reserved for government purposes. Because much of the reservation went unclaimed, the Indian Office negotiated a sale of surplus lands for a flat sum of $28,500, or about $1.10 an acre. Each tribal member was given $72 per capita for his or her part of the sale.

As the century progressed and as tribal members who had allotments died, the Indian Office approved the sale of many more acres of allotted reservation lands. C.E. Larson, the Bureau of Indian Affairs agent for the Siletz and Grand Ronde, reported on May 30, 1931, that “on the Grand Ronde Reservation there is a total of 333 [Indians] living” as “mill workers and farm helpers . . . wages, road work, and in the timber . . . they have lost practically all of the good farm land . . . [through] nonpayment of taxes and sold, mortgages, and loans.” Larsen stated that “there are only about . . . 100 that do have inherited land” and that the land was mostly “burned-over land, hill land, timbered.”

By 1931, few Indian allotments remained at Grand Ronde, and there were almost no services or support for the elder Indians who remained. In 1932, Abe Hudson testified: “We have four or five old people that need attention. . . . They sold their land; consequently, they have nothing at the present time. . . . They are in bad circumstances. Their health is not in good shape. . . . I would suggest or would ask that there would be some arrangements made whereby there should be set aside something like a few acres where they could do their own farming, raise their own crops, and supply the needs of their home if they have a home.”

Poverty was common at Grand Ronde, as many people lived in crude cabins off dirt roads with no running water, electricity, or other necessities of modern existence. The poverty on Indian reservations was considered part of the national “Indian problem,” which the government sought to solve through liquidation.

In 1936, the Bureau of Indian Affairs instituted the Rehabilitation Program, which established a cannery in the newly built Government Hall on the reservation. The BIA facilitated the creation of farms to produce products for canning, and nearly the entire Grand Ronde community took part in the project. For the few decades that the project lasted, the tribe canned meat, fish, vegetables, and fruits for sale to the public. Its best-known product was wild blackberry jam, called Gay Moccasin, which they sold to the railroad, the Meier and Frank Department Store, and boutique stores in Seattle. The canning program ended in the early 1950s with termination proceedings, but tribal members kept using the cannery into the 1970s.Tribal Elders continue to make the jam for special occasions at the reservation, and it was given as a special gift to Oregon politicians following the tribe’s restoration in the 1980s.

From the earliest days of the reservation, the Grand Ronde Tribal Council held regular community meetings. In 1873, the tribe adopted a set of twenty-two laws and a representative government of tribal leaders and a president from the major tribes on the reservation. The first elected president was George Sutton (Wapato/ Tualatin). On the council were representatives from the Luckiamutes, Yamhills, Kalapuyans, Santiams, Umpquas, Rogue River, Clackamas, Oregon City, Molels, Mary’s River, and Wapato.

On May 13, 1936, Grand Ronde joined many other tribes in the United States in establishing a constitution and bylaws under the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA), and the community elected officials and a tribal council under the new constitution. On August 22, 1936, the federal government ratified the Corporate Charter of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon. The charter established a business committee to further the economic development of the reservation’s forest resources and land. These two documents helped people at Grand Ronde integrate into the local society by allowing them to make political and economic decisions for the tribe.

In 1944, the federal government began its effort to liquidate or terminate federal responsibilities under treaty agreements for all tribes in the United States. The 1944 inventory conducted by the Bureau of Indian Affairsof the Grand Ronde Reservation reported positive social conditions at the reservation, with most members gainfully employed. At the time, many tribal people had taken war industry jobs, filling positions left vacant by people joining the military. By 1947, Congress concluded that the people on the Grand Ronde Reservation were assimilated, there was no longer any need for support, and that the tribe was ready for termination.

In 1952, the tribe agreed to the first draft termination bill, which called for an early termination of western Oregon Indians. The first bill allowed for the tribal community to keep the land they had been allotted and to manage their own timberlands. Congress decided, however, that tribal members had to purchase their land instead, and a second termination bill was submitted to the tribe in 1953. The tribe refused to approve the bill, as they were waiting for payment from their Indian Claims lawsuits for unsettled land claims payments. In March 1954, Indian Agent E. Morgan Pryse submitted the second bill to Congress, stating that the tribe agreed in principal and that many Oregon politicians as well as former Oregon governor and present Secretary of the Interior Douglas McKay agreed. Using its plenary powers to terminate agreements, Congress approved the termination of the Western Oregon Indians (Public Law 588) in 1954 without approval of the tribes involved.

For the next year and a half, the tribe had to create a termination roll of tribal members, and the government sought to settle up all accounts, including those for leases, borrowed money, business, and allotments. The tribe’s Business Committee chose to have the final payout of all money owed to the community for land sales divided equally among tribal members. Those members who had the resources could purchase their allotment from the government before the community sale of property. In 1956, the final termination rolls were submitted, and over sixty tribes in western Oregon, northern California, and southern Washington were terminated. Each Grand Ronde tribal member on the termination roll received $35 for his or her share of the land sales.

For twenty-seven years, the Grand Ronde tribe endured termination. Most members left the Grand Ronde area and sought jobs in cities, and a few took advantage of federal education or relocation programs. In the 1970s, tribal Elders Margaret Provost, Marvin Kimsey, Merle Holmes, and others began organizing the tribe for restoration. Oregon Sen. Mark O. Hatfield, Rep. Les AuCoin, and Gov. Victor Atiyeh became convinced that supporting the efforts for restoration was the best thing they could do to help solve the tribe’s many problems with health issues, poverty, and cultural loss. The tribe engaged lawyer Elizabeth Furse, who directed the Restoration Project of the Native American Program of Oregon Legal Services (NAPOLS).

Despite oppositional pressure from the regional fishing and hunting lobbies, Congress passed the Grand Ronde Restoration Act (25 U.S.C. 713 et seq.) and Pres. Ronald Reagan signed it into law on November 22, 1983. On September 9, 1988, Congress restored 9,811 acres of the original reservation by passing the Grand Ronde Reservation Act (25 U.S.C. 713f note; 102 stat. 1594).

The early years of the restored tribe were spent establishing essential governing departments. In 1995, the Spirit Mountain Casino was opened in Grand Ronde after the tribe signed a compact with the State of Oregon. The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde continues to develop working relationships with local, state, and federal agencies. In the 2000s, the tribe’s population grew to over 5,500 members with many people returning every year.

The Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is engaged in many projects that seek collaborative relationships at the state and local levels to help organizations understand the tribe’s history. The Signs Project is establishing interpretive signs throughout the tribe’s homelands, those lands ceded to the federal government by treaty. Since the late 1970s, the tribe has published Smoke Signals, a newsletter that has won local and national awards. In 2010, the tribe finished building a traditional plankhouse on the reservation. In 2011, the Culture Department installed an exhibit, Grand Ronde Canoe Journey, at the Mission Mill in Salem to tell the story of the tribe’s canoe traditions. Veterans and summer powwows and a spring Round Dance are held each year at the reservation. Since the early 2000s, the tribe has a language immersion program for Chinuk Wawa in kindergarten and first grade classes, and in 2012 it published Chinuk Wawa: As We Speak It, a dictionary of the Chinuk Wawa language.

-

![]()

Closeup of the Grand Ronde Governance Building.

Courtesy Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community -

![Grand Ronde Restoration Hearing, 1983]()

Grand Ronde Restoration Hearing, 1983.

Grand Ronde Restoration Hearing, 1983 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 101587

-

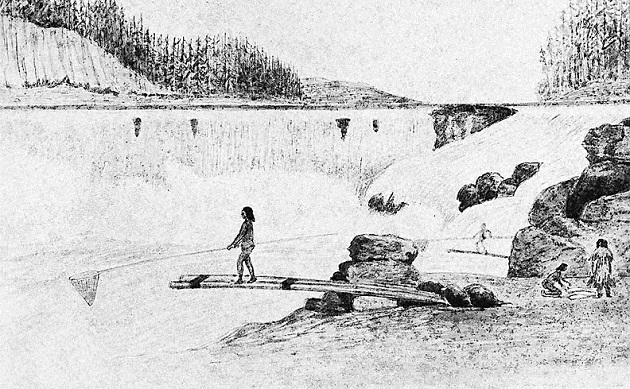

![Indians Fish at Willamette Falls, 1841. OrHi 46193]()

Indians Fish at Willamette Falls, 1841..

Indians Fish at Willamette Falls, 1841. OrHi 46193 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 46193

-

![Grand Ronde Governance Building]()

Grand Ronde Governance Building.

Grand Ronde Governance Building Courtesy Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community

-

![Spirit Mountain]()

Spirit Mountain.

Spirit Mountain Courtesy Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community

-

![Spirit Mountain Casino]()

Spirit Mountain Casino.

Spirit Mountain Casino Courtesy Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community

-

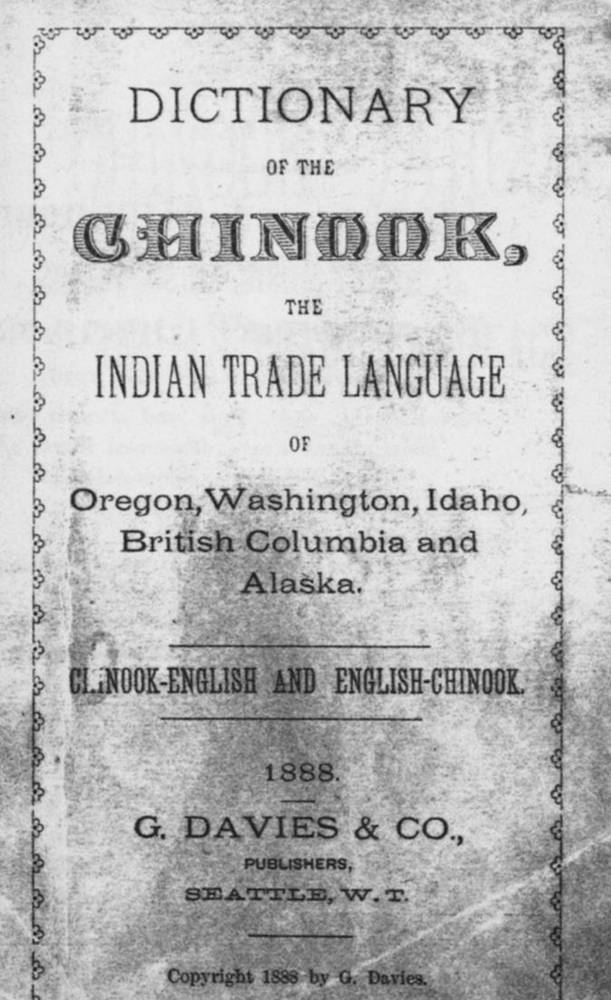

![]()

Chinook Jargon dictionary, 1888, title page.

University of Washington Special Collections

-

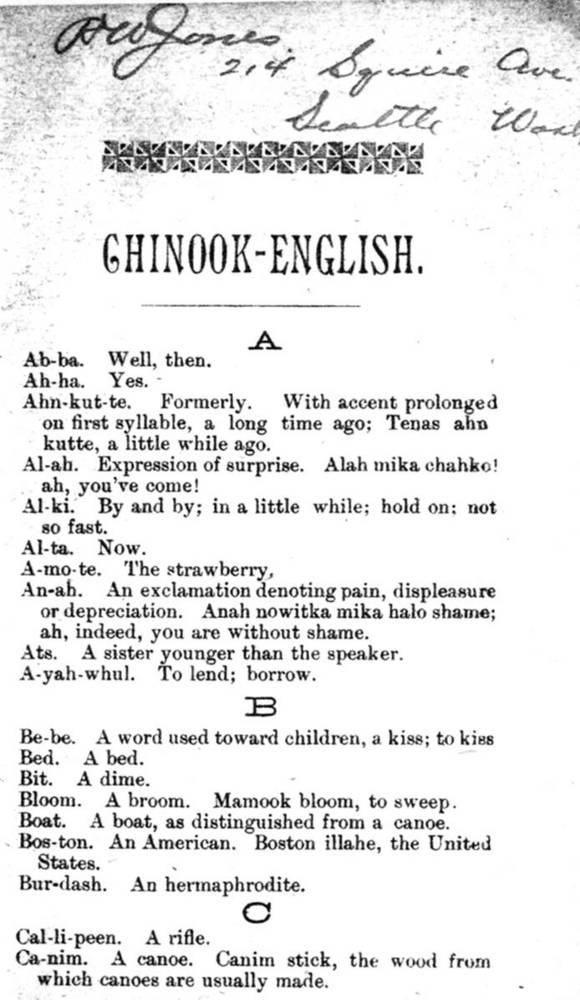

![]()

Chinook Jargon dictionary, 1888.

University of Washington Special Collections

-

![]()

Chinook Jargon dictionary, 1888, p. 7.

University of Washington Special Collections

Related Entries

-

![Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation]()

Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation

In September 1856, Joel Palmer, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs fo…

-

![Athapaskan Indians]()

Athapaskan Indians

According to Tolowa oral histories, the Athapaskan people of southern O…

-

![Chemawa Indian School]()

Chemawa Indian School

Chemawa Indian School, located in the mid-Willamette Valley north of Sa…

-

![Chinook Jargon (Chinuk Wawa)]()

Chinook Jargon (Chinuk Wawa)

According to our best information, the name "Chinook" (pronounced with …

-

Coast Indian Reservation

Beginning in 1853, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer negotia…

-

![Fr. Adrien Croquet (1818-1902)]()

Fr. Adrien Croquet (1818-1902)

Father Adrien-Joseph Croquet (pronounced “Crockett” locally) arrived in…

-

Hallie Ford Museum of Art

The Hallie Ford Museum of Art at Willamette University has only been in…

-

Indian Boarding Schools

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, only one Indian boarding …

-

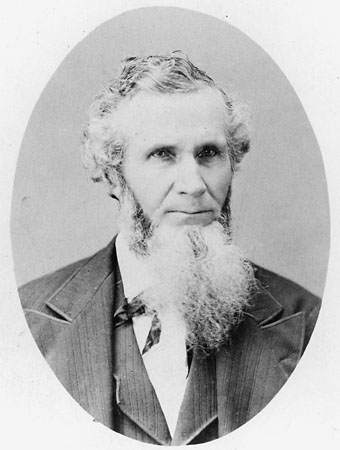

![Joel Palmer (1810–1881)]()

Joel Palmer (1810–1881)

Joel Palmer spent just over half of his life in Oregon. He first saw th…

-

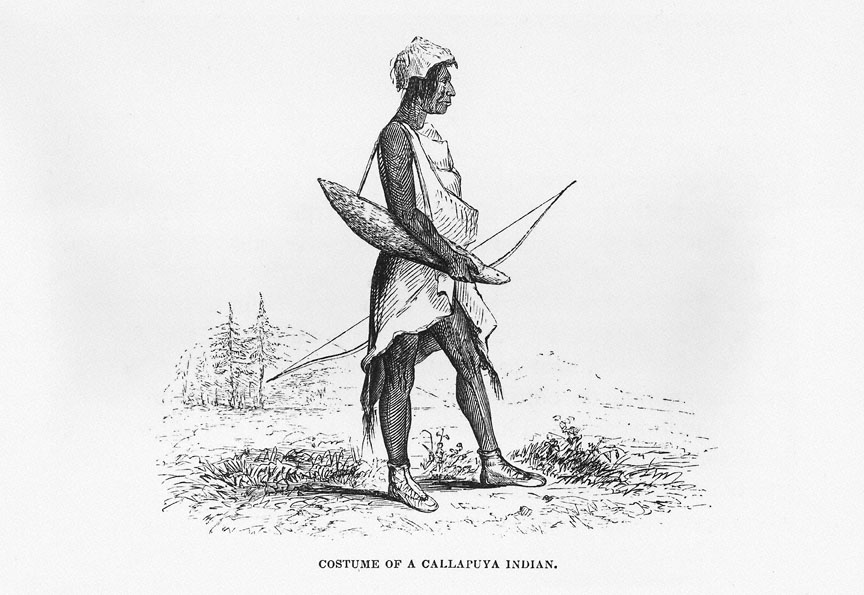

![Kalapuya Man Drawing]()

Kalapuya Man Drawing

Costume of a Callapuya Indian, also known as Kalapuya Man, is one of th…

-

![Kalapuyan peoples]()

Kalapuyan peoples

The name Kalapuya (kǎlə poo´ yu), also appearing in the modern geograph…

-

![Kalapuya Treaty of 1855]()

Kalapuya Treaty of 1855

The treaty with the Confederated Bands of Kalapuya (1855) is the only r…

-

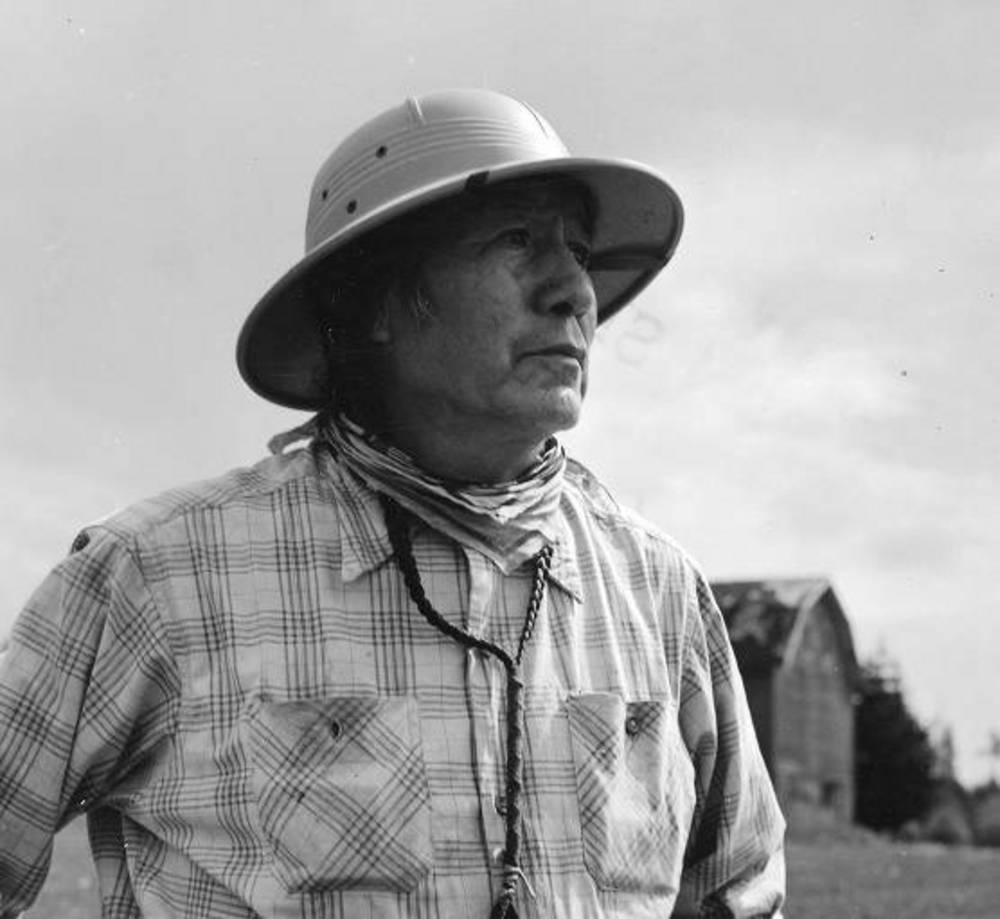

![Kathryn Harrison (1924-2023)]()

Kathryn Harrison (1924-2023)

Kathryn Jones Harrison of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde was on…

-

![Native American Agricultural Labor]()

Native American Agricultural Labor

As early as the 1830s, when French Canadians associated with the Hudson…

-

![Native American Loggers in Oregon]()

Native American Loggers in Oregon

In pre-settlement times, native peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast …

-

![Oregon Donation Land Law]()

Oregon Donation Land Law

When Congress passed the Oregon Donation Land Law in 1850, the legislat…

-

![Philip Henry Sheridan (1831-1888)]()

Philip Henry Sheridan (1831-1888)

Before he gained fame as commander of the cavalry forces of the Army of…

-

![Table Rock Treaty of 1853]()

Table Rock Treaty of 1853

The Council of Table Rock brought a temporary peace between Indigenous …

-

![Tualatin peoples]()

Tualatin peoples

Tualatin (properly pronounced 'twälə.tun in English) was the name of a …

-

![Western Oregon Klikatats (Klickitats)]()

Western Oregon Klikatats (Klickitats)

Between the 1810s and 1850s, a sizable segment of the Klikatat Tribe of…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Beckham, S.D. Oregon Indians: Voices From Two Centuries. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2006.

Beckham, S.D. The Indians of Western Oregon: This Land Was Theirs. Coos Bay, Ore.: Arago Books, 1977.

Hadja, Y. The Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon: The First Oregonians. Portland, Ore.: Council for the Humanities, 1992.

Lewis, D.G. "Termination of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon: politics, community, identity." PhD diss. University of Oregon, 2009.

Mackey, H. The Kalapuyans: a sourcebook on the Indians of the Willamette Valley. Salem, Ore.: Mission Mill Museum Association, 1974.

Olson, K. Standing tall: the lifeway of Kathryn Jones Harrison, chair of the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 2005.

Zenk, H.B. "Chinook Jargon and Native Cultural Persistence in the Grand Ronde Indian Community, 1856-1907: A Special Case of Creolization." PhD Diss. University of Oregon, 1984.

Zucker, J., K. Hummel, et al. Oregon Indians: culture, history & current affairs, an atlas & introduction. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1983.