The Crooked River Basin lies in the heart of central Oregon, east of the Cascade Mountains and Deschutes River and south of the John Day River. The appropriately named Crooked River, fed primarily by mountain creeks and springs, twists and turns for 155 miles before emptying into the Deschutes River and Lake Billy Chinook. In some sections, the Crooked has carved deep canyons through the landscape; in others, a broad floodplain reveals the river's historic penchant for creating new channels during heavy floods.

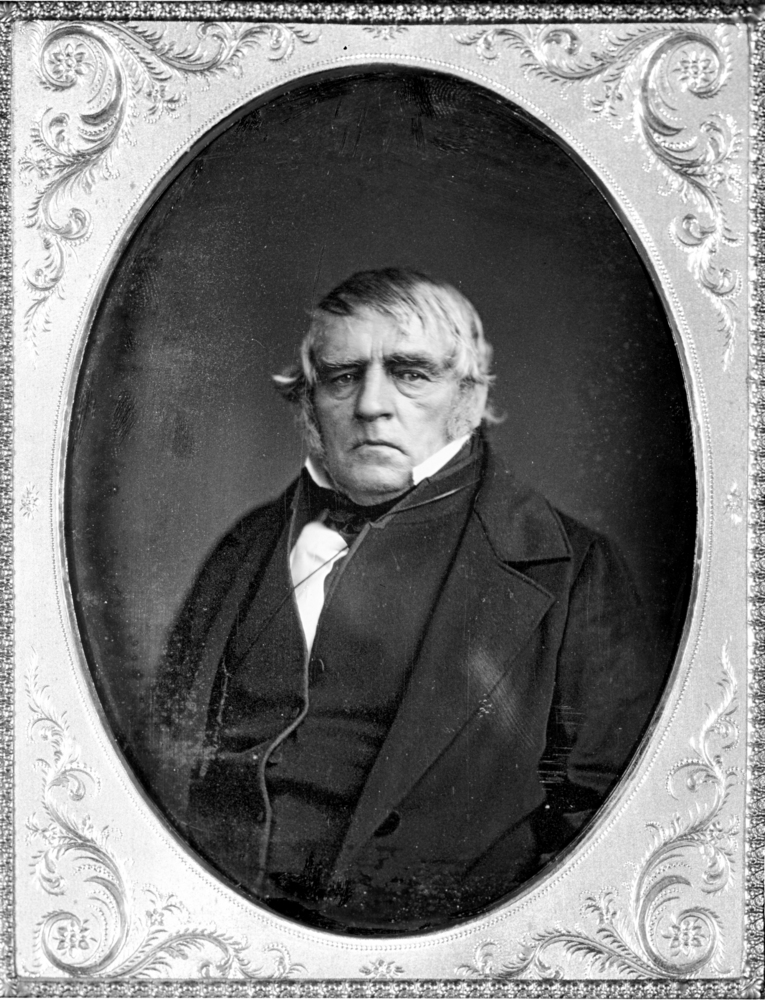

The journals of early travelers describe the region before widespread EuroAmerican settlement began taking place in the 1860s. Peter Skene Ogden, a Hudson's Bay Company fur trapper, led several expeditions through the High Desert, searching for beaver. He saw grasses standing "seven feet high" and streams lined with willow. The benchlands above the Crooked River valley, he wrote, were "a most dreary barren country." Ogden also came across several large "Indian camps," an "Indian weir" for catching fish, and evidence that Native Americans, mostly likely Northern Paiutes, had set fire to meadow grasses.

Early travelers' journals paint two pictures of the Crooked River Basin. Along the river valleys, beaver dams and wetlands created vast riparian areas, which encouraged biological diversity. Considerable stands of grasses and willows thrived in the rich soils, and anadromous fish (fish which live in the ocean but breed in fresh water), such as salmon and trout, spawned in the river. Above the river, the benchlands exhibited fewer signs of life. Separated from the river and plagued by low rainfall, the landscape was rocky, exposed, and dotted with few trees. What did grow were tufts of hearty bluebunch wheatgrass, which resisted drought and nourished the wildlife and, eventually, the cattle, that roamed the region.

These early travelers' accounts describe an austere environment and the vital importance of the Crooked River as the lifeblood of a harsh terrain. The first EuroAmerican settlers, arriving in the 1860s, settled in the floodplains, where the river's annual flooding replenished the soil and naturally irrigated the area's native grasses.

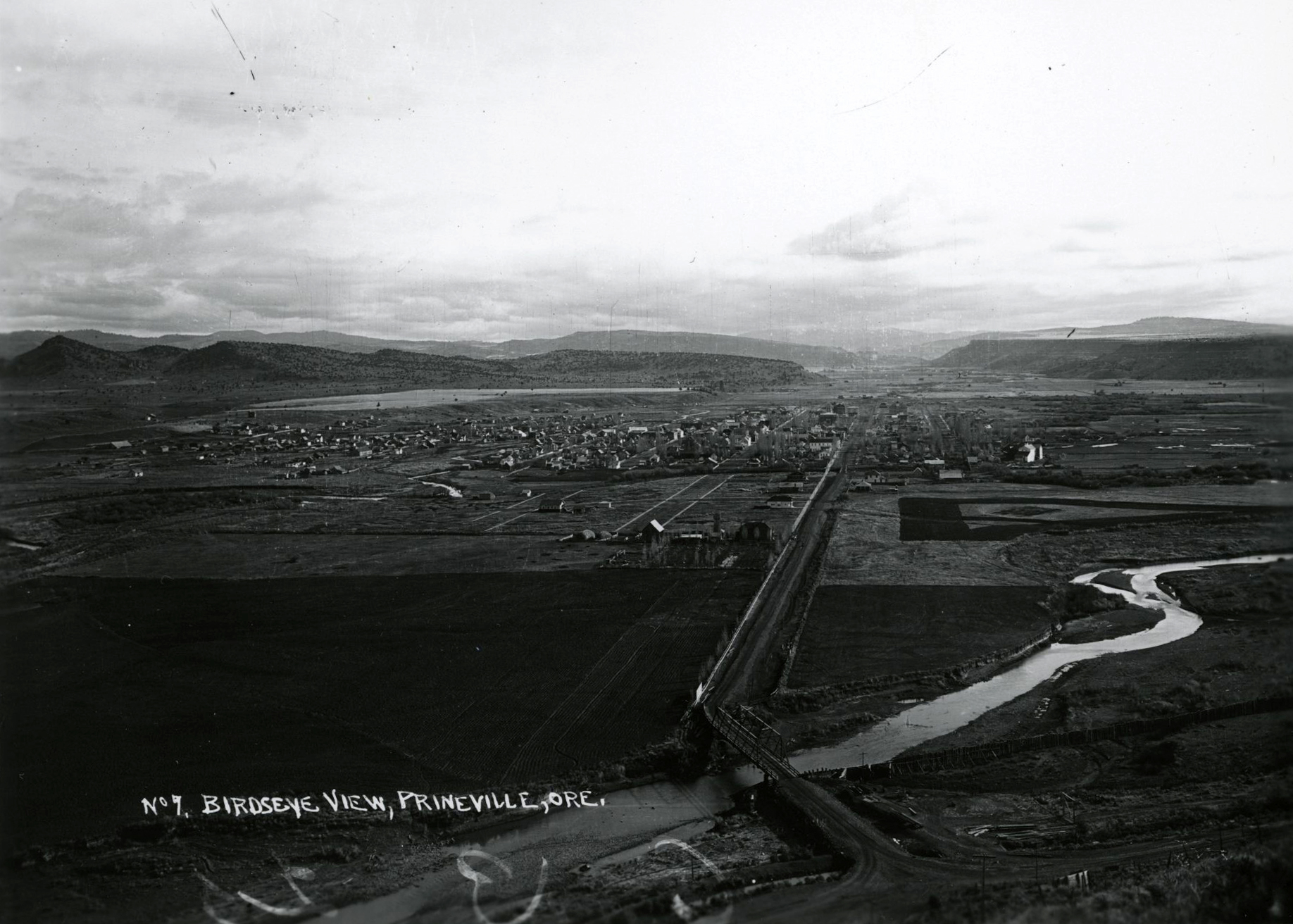

The Crooked River Basin's main town, Prineville, was settled in 1871 (incorporated in 1880) as "Prine," named for Barney Prine, who settled in the broad floodplain where the Crooked River and its main tributary, Ochoco Creek, meet. It became Prineville in 1872. The town's location, in the center of Oregon's burgeoning cattle country, helped Prineville become an important place for trading cattle in Oregon at the turn of the nineteenth century.

The booming cattle and sheep industries of the early twentieth century brought new settlers and land and water scarcity to the region. Grazing wars between sheep and livestock ranchers plagued Central Oregon in the 1910s. Landowners and governmental agencies soon realized that open grazing in the area was incompatible with the influx of people and livestock. Irrigation became indispensable for landowners raising livestock and homesteaders attempting to farm.

After several private attempts to irrigate large areas of the Deschutes and Crooked River Basins in the early twentieth century failed, state and federal agencies launched joint investigations into large public reclamation projects. In 1915, Oregon state water engineer, John Whistler, and the federal Reclamation Service published a plan for irrigating nearly 20,000 acres of Crooked River Basin lands by damming Ochoco Creek. While the state and federal government did not act on that project, local landowners used the plan to raise funds for a privately financed dam on the creek. Construction ended in 1921, but the project rarely delivered as much water as anticipated and quickly ran into financial troubles.

The Ochoco Creek dam not only altered the Crooked River's hydrology by creating a large lake in the watershed, it also started a long process of local farmers looking for federal assistance for their failed irrigation district. In 1956, after working closely with Oregon U.S. senators Wayne Morse and Richard Neuberger, local officials and landowners celebrated Congress's authorization of the Crooked River Project, a dam and irrigation works for 20,000 acres of basin lands. Bowman Dam was completed in 1961 to store water for irrigation and for flood control.

The new dam and reservoir had a significant impact on agriculture, fish habitats, and recreation in the basin. Demand for recreational opportunities pushed the state to create Prineville State Park on the reservoir in 1962. Three years earlier, the state had created Smith Rock State Park twenty miles downstream, increasing the Crooked River's recreational draw.

In addition to the state parks, the regulation of water from the dam changed the river's habitat for fish. While the dam and reservoir curtailed native fish populations from the upper sections of the river, the release of cool water from the bottom of the reservoir during the hot summer months transformed a section of the lower Crooked River into an anglers' playground. Along with irrigation, Oregonians placed new demands on the river, forcing agricultural, recreational, and fish and wildlife interests to forge a new vision for the river—a vision that continues to evolve.

-

![Crooked River, 1920.]()

Crooked River, aerial, 1920.

Crooked River, 1920. Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Gifford Photo. Coll., Deschutes Basin Explorer, P020:0756

-

![Confluence of the Deschutes and Crooked Rivers, 1940.]()

Crooked River, confluence with Deschutes River, 1940.

Confluence of the Deschutes and Crooked Rivers, 1940. Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Gifford Photo. Coll., Deschutes Basin Explorer, P218:RIG 0853

-

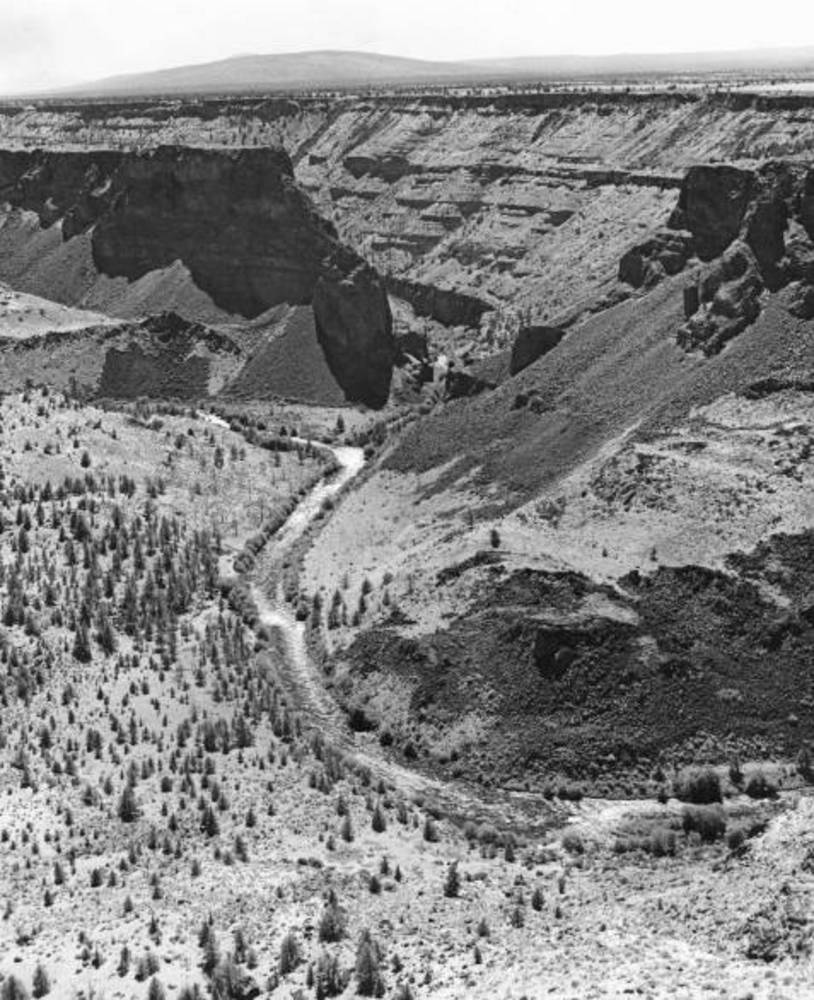

![Crooked River Canyon, 1940.]()

Crooked River canyon, 1940.

Crooked River Canyon, 1940. Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Gifford Photo. Coll., Deschutes Basin Explorer, P218:RIG 0664

-

![Crooked River, 1938.]()

Crooked River, bridge and train at, 1938, Orhi 094335.

Crooked River, 1938. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 094335

Related Entries

-

![Crooked River Project]()

Crooked River Project

In 1956, with the help of Oregon senators Wayne Morse and Richard Neube…

-

![High Desert]()

High Desert

Oregon’s High Desert is a place apart, an inescapable reality of physic…

-

![Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)]()

Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)

More than any other figure during the years of the Pacific Northwest's …

-

![Prineville]()

Prineville

Prineville, the county seat of Crook County, sits on ceded land once be…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Brogan, Phil. East of the Cascades. Portland: Binfords and Mort, 1965.

Bureau of Reclamation. Deschutes Project, Central Division: Potentials for Expansion and Improvement of Water Supplies. Boise, Idaho: Pacific Northwest Region, 1972.

Rich, E.E., ed. Peter Skene Ogden's Snake Country Journals 1825-1826. London: Hudson's Bay Record Society, 1950, 106-108.