Homer Calvin Davenport was one of the most important and influential political cartoonists working in the United States during the end of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth. A native of Silverton, Oregon, he worked with prominent newspaper editors and developed a friendship with Theodore Roosevelt, who was the subject of many of Davenport's cartoons. He was also a skilled breeder of horses, a line of which became known as the Davenport Arabians.

Davenport was born in the Waldo Hills, several miles south of Silverton on March 8, 1867. He was the fourth child of Timothy Woodbridge Davenport, who arrived in Oregon in 1851, and Florinda "Flora" Geer Davenport, who arrived in Oregon in 1847.

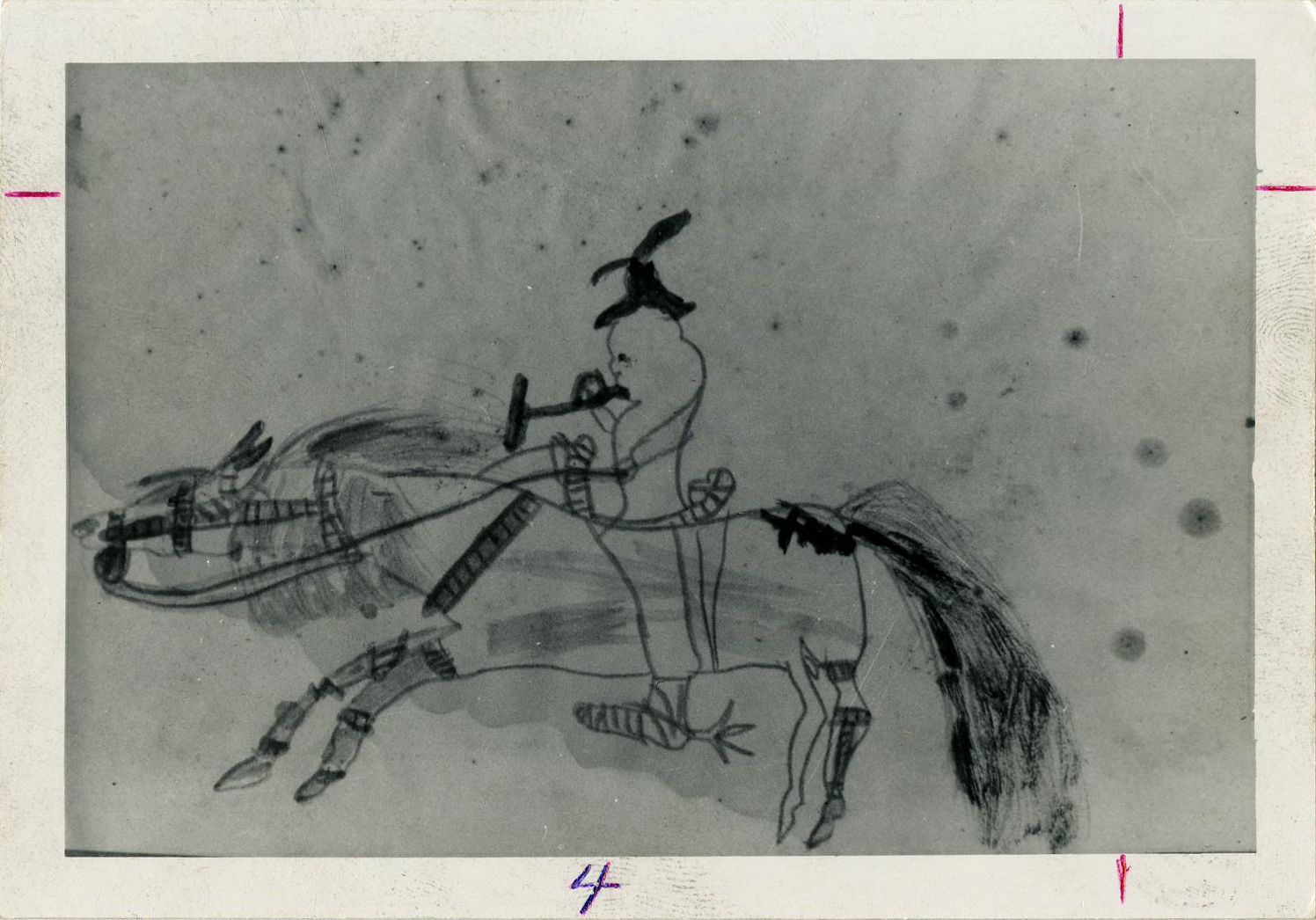

Davenport's mother was an avid fan of Thomas Nast (1840-1902), a cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly who made his name in part by using his art to expose corruption. Flora died of smallpox in 1870 when Homer was three years old, and on her deathbed, family lore has it that she asked her husband to nurture Homer’s art above all else. According to his father’s account, published in 1899, Homer drew continuously from before the age of three.

Homer Davenport drew throughout his youth, and in 1889 he was sent, at his father’s insistence, to San Francisco to attend the Mark Hopkins School of Art. He was expelled after a month due to his focus on cartooning, and returned to Oregon. During 1889 and into 1890, he offered his services for free to the Portland Evening Telegram, which published many of his illustrations.

His first paid published work, a line drawing of the steamboat Columbia Queen shooting the Columbia Cascades, appeared in the Oregonian on May 19, 1890. After several months, often working for no pay, he was laid off. During this time, he attended the Armstrong Business College in Portland, but dropped out after several months.

In 1891, Davenport pitched the Sunday Mercury, a weekly sporting paper, to illustrate the middleweight boxing match in New Orleans. T.W. Davenport sent several of his son’s images to his cousin, William Henry Smith, a manager at the Associated Press, who showed them to the head of the San Francisco Examiner’s art department. The next year, Davenport was back in San Francisco and briefly at Mark Hopkins Art School, after which he bounced between the Examiner and the Chronicle, where editor and publisher Michael Henry de Young put his skills at caricature to use.

Davenport was assigned to the Chicago Herald in 1893 to cover the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. During the fair, Daisy Moors, whom Homer had dated briefly, arrived from San Francisco. Davenport married Moors before returning to San Francisco and the Chronicle. The next year, Davenport illustrated San Francisco’s Mid-Winters Fair, an exposition organized by de Young and others. Rival publisher William Randolph Hearst of the Examiner made note of Davenport’s work and hired him at triple his Chronicle salary. Davenport was part of Hearst’s team that took control of the New York Journal in 1895, launching the so-called Yellow Journalism Wars, a competition among New York City daily newspapers who tried to outdo each other with increasingly sensational news and illustrations.

During his time with the Journal, Davenport created some of his most memorable images. During the 1896 presidential campaign, he focused on William McKinley’s wealthy industrialist campaign manager, Marcus Hanna, whom he depicted as a hulking brute wearing “plutocratic plaid” with a tiny dollar mark in each square. A year later, Davenport’s work inspired a failed Anti-Cartoon Bill in the New York State Assembly. In 1904, one of his cartoons of Uncle Sam with his hand on the shoulder of Theodore Roosevelt is said by many to have enabled the president’s election.

In 1902, Davenport was hired by James Pond, a successful lecture manager, to join the lecture circuit, and he traveled in the United States and Europe speaking about cartoons, satire, and Silverton, his beloved hometown. He published two collections of his artwork, Cartoons by Davenport (1897) and The Dollar or the Man (1890). My Quest of the Arabian Horse (1908) documents his trip to Syria to buy purebred Arabian horses, and Davenport's line of American-born Arabian horses endures as descendants of the breeding herd he acquired in 1906. His final book, The Country Boy (1910), is an autobiography about growing up in post-pioneer rural Oregon.

In April 13, 1912, Davenport was sent to illustrate the sinking of the Titanic. He contracted pneumonia waiting to interview the survivors and died on May 2. Hearst had Davenport’s body returned to Silverton for burial and paid for the funeral. The Freethought service was officiated by Oregon spiritualist Jean Morris Ellis.

-

![]()

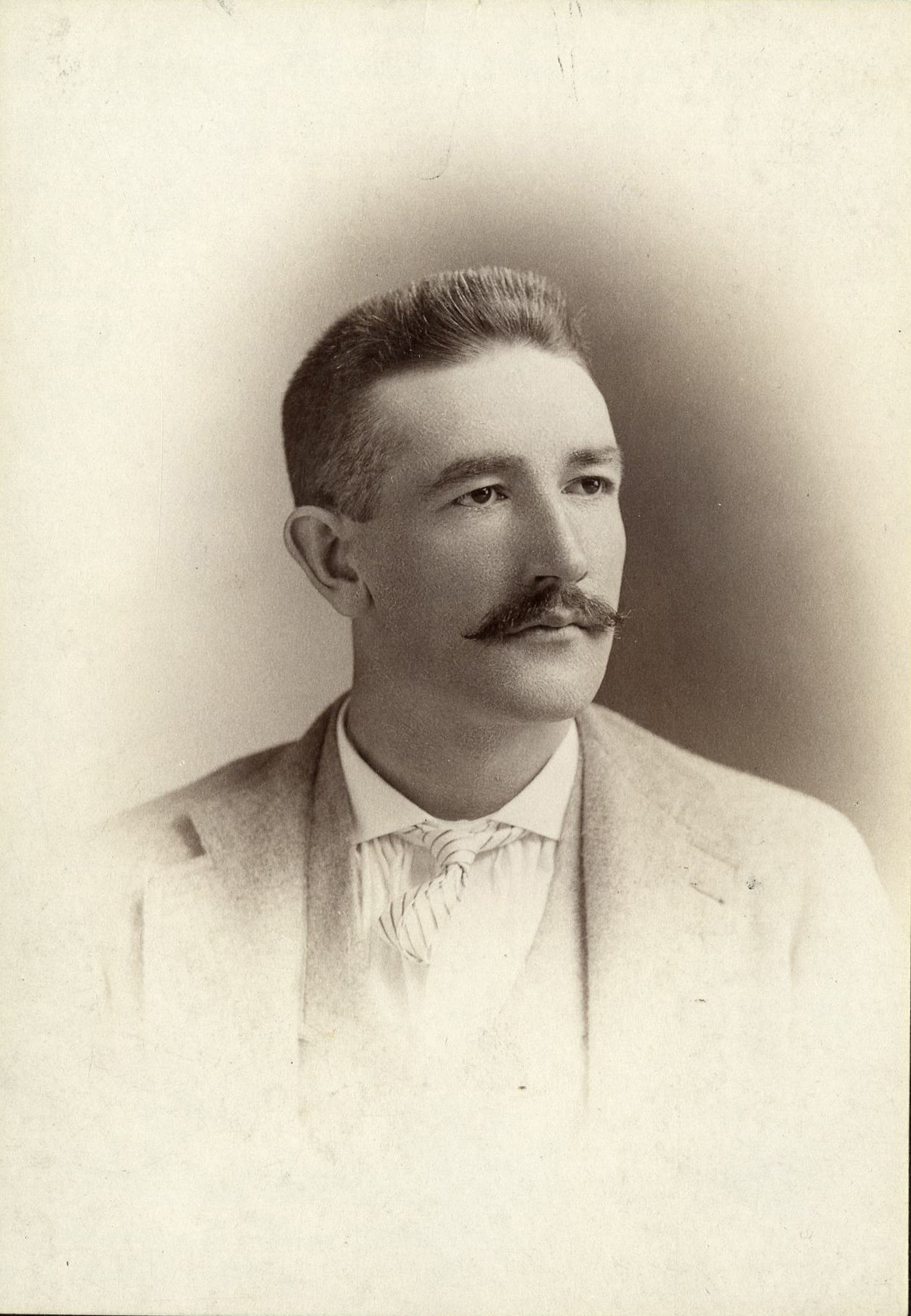

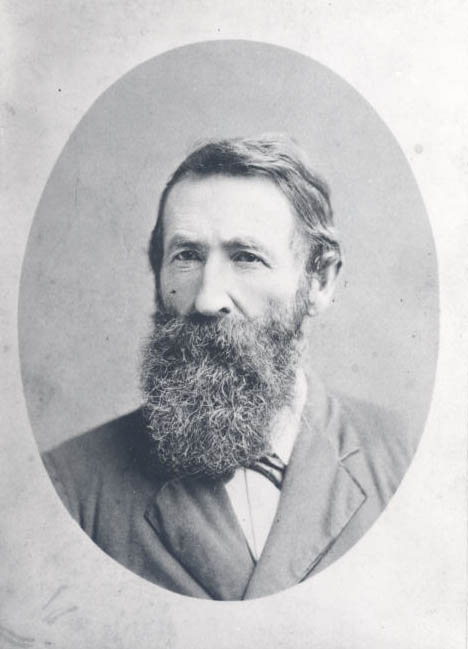

Homer Davenport in 1903.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi4136

-

![]()

Homer Davenport, self-portrait.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi4148

-

![]()

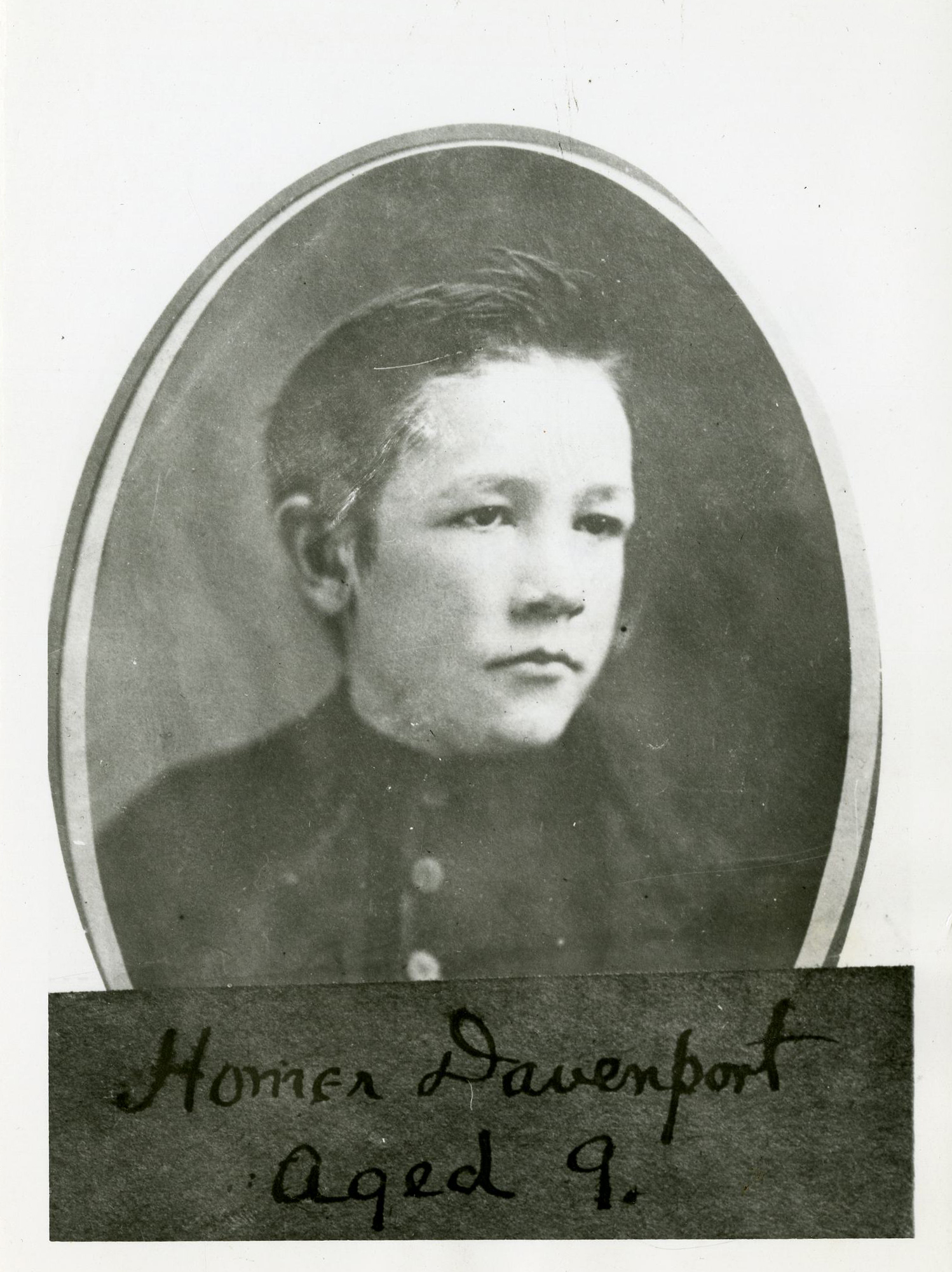

Davenport at age nine.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 38893

-

![]()

Early drawing of Arabian horse, created with a match and fruit juice, attributed to three-year-old Homer Davenport..

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Mss. 5143

-

![]()

Davenport's home in Silverton, c. 1939.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 022330

-

![]()

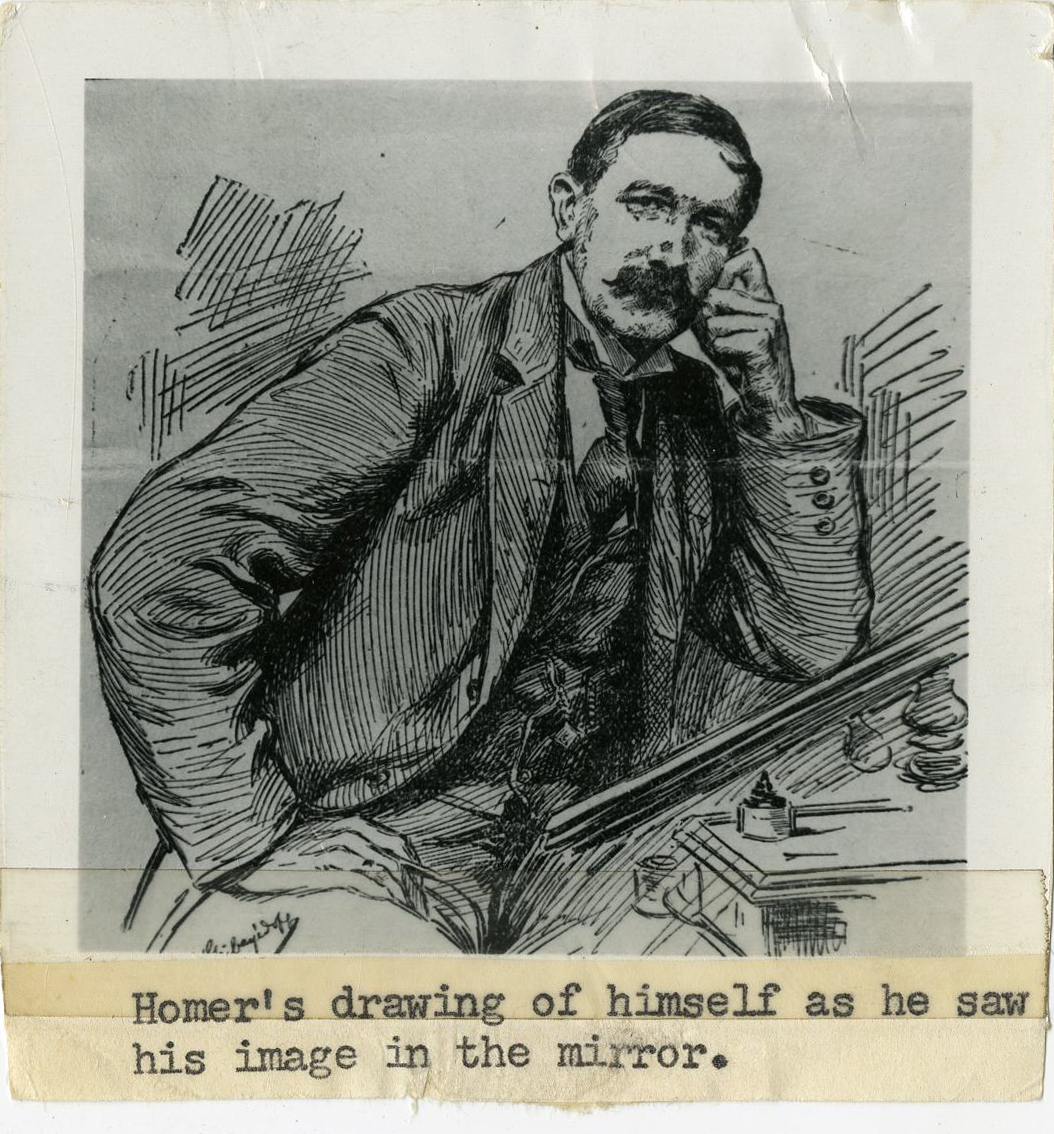

Self-portrait of Homer Davenport.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Mss. 5143

-

![]()

Davenport's political cartoon of Tammany Hall.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

![]()

Davenport's drawing of Southern Pacific president C.P. Huntington.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Mss5143, f3

-

![]()

Davenport sketch, 1899.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Mss5143, f1

-

![]()

Davenport's sketch of Asahel Bush, Oregon Statesman publisher and editor.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Mss. 5143, f3

-

![]()

Davenport sketches of poet Sir Edwin Arnold, composer Arthur Sullivan, and British politician William Gladstone.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, Mss. 5143, f3

-

![]()

Homer Davenport on a lecture tour.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

![]()

Homer Calvin Davenport (T.W. Davenport's son) with his son Homer Clyde Davenport, c.1900.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi101569

-

![]()

Davenport talks to Arthur Green and Clark Letter of the Oregonian, c. 1920.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 002261

-

![]()

Davenport's gravesite in Silverton.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

Related Entries

-

![Silverton]()

Silverton

The city of Silverton was established where Silver Creek flows northwes…

-

![Timothy Woodbridge Davenport (1826-1911)]()

Timothy Woodbridge Davenport (1826-1911)

Timothy Woodbridge “T.W.” Davenport, known as the Sage of Silverton, wa…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Bowers, Frank S. "Homer Davenport." Oregon Magazine, Silverton Number (1924).

Davenport, Homer C. Cartoons by Davenport. New York: De Witt Publishing House, 1898.

Davenport, Homer C. The Dollar or the Man? Boston, MA: Small, Maynard & Company, 1900.

Davenport, Homer C. My Quest of the Arab Horse. New York: B.W. Dodge & Company, 1909.

Davenport, Homer C. The Country Boy. New York: G.W. Dillingham Company, 1910.

Davenport, Timothy W. "Homer C. Davenport." Oregon Native Son (June 1899): 10.

Hickman, Mickey. Homer the Country Boy. Salem, Ore.: Capitol City Graphics, 1986.

Huot, LeLand, and Powers, Alfred. Homer Davenport of Silverton. Bingen, Wash.: West Shore Press, 1973.

Smith, Charles W. Letter to William H. Smith, c/o Associated Press. W.H. Smith Research Library, Indiana Historical Society, Indianapolis, IN. 1892.

Smith, Joseph P., ed. History of the Republican Party in Ohio. Chicago: the Lewis Publishing Company. 1898. Pages 196-197