Ecola State Park stretches for 1,023 acres from the north end of Cannon Beach to Seaside on Oregon’s north coast. The park encompasses hulking Tillamook Head, which rises over a thousand feet above the ocean, and miles of beaches, smaller headlands, coves, and iconic sea stacks. The rugged shoreline of Miocene lava flows, some 15 million years old, and slumping sedimentary rocks formed within an ancient mouth of the Columbia River. In his January 8, 1806, journal entry, William Clark described the landscape near the summit of Tillamook Head as “the grandest and most pleasing prospects which my eyes ever surveyed.”

When twelve members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition heard reports of a beached whale being harvested by local Indians, they traveled through what is now the park in January 1806 to trade for blubber. Both Clatsop and Nehalem-Tillamook peoples inhabited the land along the rugged shoreline and the residents of those villages, and others nearby, subsisted on seals, marine fish, shellfish of several kinds, elk, deer, and many other species. The name Indian Beach commemorates one remnant village that the Corps encountered, where epidemics had decimated the population. Members of the Expedition recorded that survivors had converted the site to a burial ground, and the beach was later named with reference to this settlement. In the course of their journey, William Clark also named a nearby creek “Ecola,” a variation of the Chinook Wawa trade language meaning “whale,” in reference to the beached whale, located just south of the creek. The term was later being applied to the park and a specific headland within its boundaries.

Protection of what is now Ecola State Park stemmed from efforts by merchants, residents, and government officials who wanted to safeguard the ships, people, and scenery on the north coast. By the 1850s, owing to their height and westward reach, Tillamook Head and other parts of the present-day park were being considered for a lighthouse to aid navigation on the approaches to the Columbia River bar. By 1866, the U.S. Lighthouse Board had proposed a lighthouse reservation for Tillamook Head. Congress appropriated $50,000 for lighthouse development in 1878 and another $25,000 in 1881. The U.S. government kept the headland largely in the public domain until the lighthouse-siting question could be resolved, but the Lighthouse Board soon lost interest in the site: the southerly faces were not visible from the mouth of the Columbia and the summit was often shrouded by fog. The southern portions were opened for private ownership, while portions of Tillamook Head remained federal property.

By the early twentieth century, members of the interrelated Glisan, Flanders, Minott, and Lewis families—prominent businesspeople and early benefactors of Portland—had constructed grand residences in the Ecola Point area. In the early 1930s, guided by a strong philanthropic ethos, the families created the Ecola Point and Indian Beach Corporation to coordinate the transfer of 451 acres between Indian Beach and Chapman Point to the fledgling state park system. Working collaboratively with State Parks Superintendent Samuel Boardman, the families agreed to dismantle their grand Ecola Point homes so that park facilities could be constructed for the public. All members of the corporation except L.A. Lewis donated their landholdings (Lewis received $17,500 for his land). The park was dedicated in 1932, and Boardman coordinated with the National Park Service for Civilian Conservation Corps crews to develop public trails, picnic facilities, and other amenities in the new park.

Buoyed by early successes and strong public support, Boardman and his successor, Chester Armstrong, sought to expand the park. Boardman was especially concerned about protecting Ecola’s rugged coast from erosion and future development. He tried to acquire the former lighthouse reservation land at Tillamook Head, but the property was pressed into military use during World War II for a radar installation, accessed by military roads still used by park visitors today. The Oregon Highway Commission appealed to the War Department for that land in 1948, as the radar facility and other military facilities were being decommissioned, and it applied for the land again, this time to the Air Force, in 1951. Finally, the state acquired nearly 100 acres on Tillamook Head.

Negotiating with the Crown Zellerbach Corporation, Boardman also obtained private logged timberland on the eastern slopes of Tillamook Head. Subsequent purchases of private properties expanded the park to its current size by 1978. The Elmer Feldenheimer State Natural Area, an abutting but independent state park unit east of Ecola, was added by 1990. Landslides have been a perennial challenge; a 1961 slide of some 125 acres, for example, pitched scenic headland forests, trails, and many CCC-era facilities into the sea.

The Oregon Coast Trail runs through Ecola State Park for more than fifteen miles, from the north boundary of the park to its southern end—a segment that is also sometimes independently called the Lewis and Clark Discovery Trail. Designated as a National Recreation Trail in 1972, this part of the Oregon Coast Trail approximates the route of Captain Clark, Sacagawea, and other members of the Corps of Discovery and is a favored hike for park visitors.

Ecola State Park is a popular visitor destination, with an average annual attendance of more than 500,000 people.

-

![]()

Ecola State Park, 1936.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, 013138

-

![]()

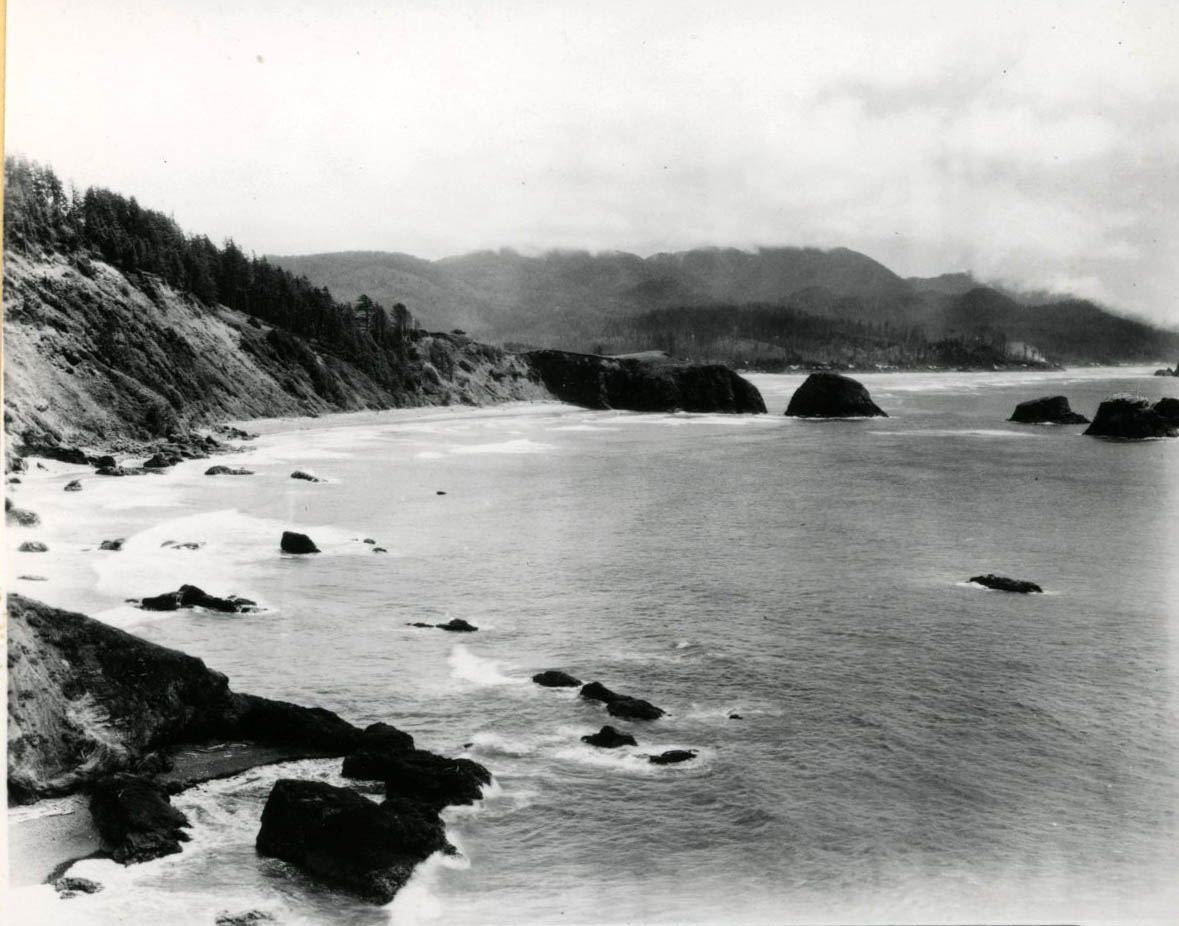

Looking north at Indian Beach, Ecola, Tillamook Head in distance, 1934.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Journal, 017989

-

![]()

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) landscapes Ecola State Park, 1938.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 019098

Related Entries

-

![Lewis and Clark Expedition]()

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Expedition No exploration of the Oregon Country has greater histor…

-

![Oregon Coast Trail]()

Oregon Coast Trail

Winding for 382 miles along the Oregon Coast, the Oregon Coast Trail is…

-

![Samuel H. Boardman (1874-1953)]()

Samuel H. Boardman (1874-1953)

As the first state parks superintendent in Oregon, serving from 1929 to…

-

![Tillamook Rock Lighthouse]()

Tillamook Rock Lighthouse

Tillamook Rock Lighthouse sits on a rock a mile offshore of Tillamook H…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Armstrong, Chester H. History of the Oregon State Parks: 1917-1963. Salem: Oregon State Highway Department, 1965.

Deur, Douglas. Empires of the Turning Tide: A History of Lewis and Clark National Historical Park. Pacific West Region: Social Science Series, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2016.

Merriam, Laurence C., Jr. Oregon’s Highway Park System, 1921-1989: An Administrative History. Salem: Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, 1992.