Fort Vancouver, a British fur trading post built in 1824 to optimize the Hudson’s Bay Company’s operations in the Oregon Country, was the headquarters and central supply depot for the HBC’s operations west of the Rocky Mountains. It was, according to the company’s governor Sir George Simpson, “the great centre of the business of the west side of the Continent.”

From Russian Alaska to Mexican California and from the crest of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean, HBC employees worked at more than a dozen trading posts, sailed in trading vessels, and traveled in brigades of trappers, collecting furs to send to Fort Vancouver where they were counted, cleaned, and shipped to England as part of the global fur trade. In return, ships from Britain supplied the fort with necessary goods and other items to be distributed to the company’s posts, traded to Natives for furs and other resources, and sold throughout the region and at mercantile posts in the Hawaiian Islands and Yerba Buena (present-day San Francisco). Described as “the grand emporium of the company’s trade, west of the Rocky Mountains” by former HBC clerk John Dunn, Fort Vancouver was the center of Euroamerican politics, economics, and culture in the Pacific Northwest. It was also the early terminus of the Oregon Trail.

After the North West Company and HBC merged in 1821, the company’s governor and committee (board) considered what to do with the Oregon Country, which Great Britain jointly occupied with the United States. The HBC ultimately viewed the region as a “defensive zone” important in protecting its lands farther north and east, and the company began strengthening its presence in the region to reinforce Britain’s claim on the Columbia River as an international border.

Beginning in 1824, the establishment of posts such as Fort Vancouver, the initiation of a Northwest coastal trade, and the practice of trapping fur-bearing animals to extinction south of the Columbia to make that region less attractive to Americans—known as the fur desert policy—combined to introduce a significant British presence to the Oregon Country. Though Fort Vancouver was originally thought of as a secondary post—the hope was that a post at the mouth of the Fraser River would become the regional headquarters—by the 1840s the fort was the company’s western administrative headquarters and primary depot.

The location of Fort Vancouver at the confluence of the Columbia and Willamette Rivers proved its early success but also led to its eventual demise. Known by the Klickitat people as Alaek-ae (the place of the mud turtles) and by fur trappers as Jolie Prairie, the gently sloping prairie grassland ringed by a dense fir forest offered many advantages. The location had a favorable climate and hundreds of acres of pasture and farmable land that made the post less reliant on costly food from Britain. It was also a politically advantageous site because it was located on the north side of the Columbia River, a prospective international boundary favored by the HBC. In 1825, the company transferred its depot from Fort George, at the mouth of the river, to Fort Vancouver; Fort George was reopened as a minor post four years later.

Construction of Fort Vancouver began in late 1824 on a ridge just north of the prairie (near the present-day Washington School for the Deaf), and HBC Governor Simpson dedicated it as Fort Vancouver on March 9, 1825. “The object of naming it after that distinguished navigator [George Vancouver],” he wrote, “is to identify our claim to the Soil and Trade with his discovery of the River and Coast on behalf of Gt Britain.”

By 1829, the company had designated Fort Vancouver as the permanent depot for its Columbia Department. That year, Chief Factor John McLoughlin, working under Simpson’s direction, relocated the fort to the lower plain, closer to the Columbia but beyond the reach of annual freshets, in a location marked today by the National Park Service’s reconstructed Fort Vancouver. A wooden palisade enclosed and protected more than a dozen buildings, and a nearby village housed as many as five hundred employees and their families.

“Every thing, and of every kind and description” could be had at Fort Vancouver, Lt. Charles Wilkes of the U.S. Exploring Expedition wrote when he stopped at the fort in the fall of 1841. He made particular note of the fort's “extensive apothecary shop, a bakery, blacksmiths’ and coopers’ shops, trade-offices for buying, others for selling, others again for keeping accounts and transacting business; [and] shops for retail, where English manufactured articles may be purchased at as low a price, if not cheaper, than in the United States.”

Visitors to the fort noted the cultural diversity of its employees. While most of the company’s officers were Scottish, its working-class employees included English, French Canadian, Metís, Scottish, Irish, Hawaiian, Iroquois, and Cree and people from over thirty regional Native groups. The artist Paul Kane wrote in 1859 that there was “quite a Babel of languages” at the fort, which undoubtedly mixed with the “sound of the hammers, click of the anvils, the rumbling of the carts, with tinkling of bells,” which, Wilkes noted, permeated the fort’s grounds.

This diversity existed within a tightly controlled social hierarchy in which chief factors and chief traders represented an upper class of commissioned officers, followed in rank by gentlemen such as clerks, surgeons, and ship captains; tradesmen such as blacksmiths, carpenters, and bakers; voyageurs, including interpreters, guides, and steersmen; laborers; and charges, including retired employees, widows, orphans, and some Indian children. Officers strictly maintained this hierarchy across all company activities, including employment, pay, punishment, and access to food and housing.

Beyond its immediate structures, the agricultural potential of the surrounding land was important for the success of Fort Vancouver. On several hundred acres of rich meadows and bottomlands, McLoughlin set in motion George Simpson’s vision of self-sufficiency through agriculture. Employing more physical space and more personnel than any other activity and using mostly Native and Hawaiian laborers, McLoughlin initiated the region’s first large-scale farming, which grew from 120 acres cultivated in 1829 to 1,420 acres in 1846. HBC had enough surplus production to fulfill an 1839 treaty commitment to the Russian America Company by supplying foodstuffs in exchange for fur-gathering rights in northern Russian-controlled areas and to sell to arriving American emigrants in the early 1840s.

Industries important to Oregon’s present-day economy can trace their start to Fort Vancouver, as the HBC focused on natural resource extraction as a means to economic profit. Commodities such as salmon and lumber were systematically harvested and exported through the fort’s mills and processing plants, wheat and other grains were processed through the region’s first mills, and large dairy and livestock operations expanded the company’s footprint to places such as present-day Sauvie Island. McLoughlin initiated the region’s shipbuilding industry at Fort Vancouver in 1827, and the fort eventually became the headquarters for the HBC’s seven-vessel Marine Department, including the first steam-powered vessel in the Pacific Northwest, the Beaver. He also supported education for the children of his employees, hiring educators and establishing a school.

The HBC's profit-driven system of commerce based at Fort Vancouver succeeded for several decades, but not without costs. In addition to the environmental consequences of extracting natural resources at often unsustainable rates, the system quickly dominated the trade networks that the region’s Native peoples had used for centuries and contributed to the breakdown of their traditional practices and ways of life.

Concerns over growing American emigration, the dangers of the Columbia River bar, and the impending boundary settlement between the U.S. and Great Britain led the HBC to designate Fort Victoria as the company’s new depot in 1845. With the Oregon Treaty of 1846, the site of Fort Vancouver fell within the boundary of the United States. The HBC continued only a small presence there, leasing buildings and land to the U.S. Army until a dispute with Gen. William S. Harney led the company to turn over the keys to the post and depart in 1860. It was not until 1869 that a joint commission awarded the HBC a settlement for the value of lands, rights, and improvements south of the international boundary, to include Fort Vancouver. Meanwhile, in 1853 the army officially named their post established in 1849 Fort Vancouver; it was renamed Vancouver Barracks in 1879.

Over time, the site of the fort was lost to the public. Renewed interest led to archaeological investigations in the 1940s that located the site of the stockade walls, which led to its designation in 1949 as a national monument—and later, a national historic site—administered by the National Park Service. Archaeology also informed the National Park Service's process of reconstructing the fort's palisade walls and many interior buildings, beginning in the 1960s. Today, more than two million artifacts and museum collections from sites throughout the Pacific Northwest are curated by the National Park Service at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

-

![Sketch of Fort Vancouver by H.J. Warre, c. 1845]()

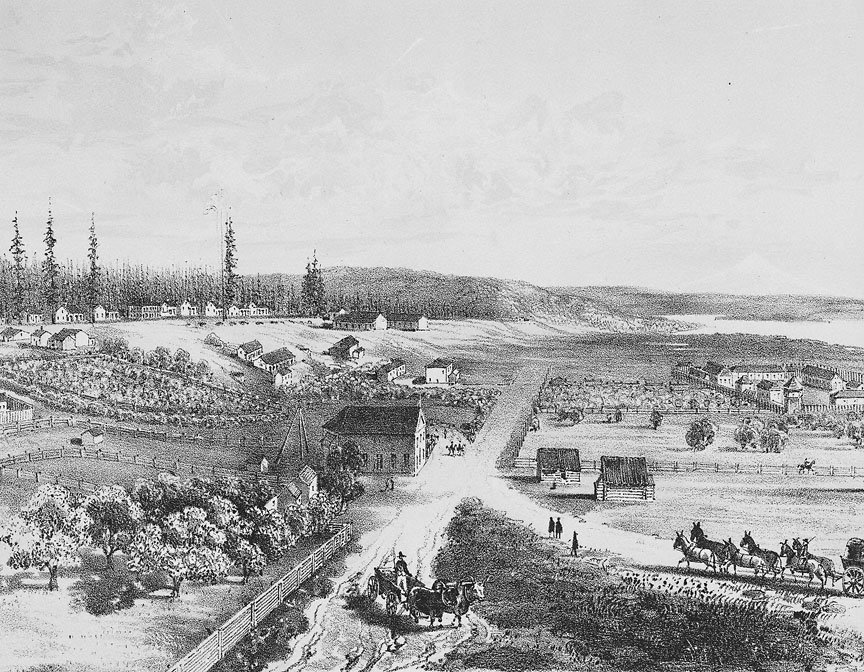

Sketch of Fort Vancouver by H.J. Warre, c. 1845.

Sketch of Fort Vancouver by H.J. Warre, c. 1845 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi83437

-

![John McLoughlin]()

John McLoughlin.

John McLoughlin Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi067763

-

![George Simpson]()

George Simpson.

George Simpson Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi10125

-

![A tree planted in 1826 with seedlings from England still stands on the grounds of Fort Vancouver and Barracks.]()

Old apple tree, Fort Vancouver.

A tree planted in 1826 with seedlings from England still stands on the grounds of Fort Vancouver and Barracks. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 992D065

-

![Thomas Vaughan dedicates the fort; Tom McCall is in the audience.]()

Dedication of Fort Vancouver, 1974.

Thomas Vaughan dedicates the fort; Tom McCall is in the audience. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

![Photo by Al Monner]()

Fort Vancouver dedication ceremony, 1974.

Photo by Al Monner Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

![]()

Fort Vancouver, restored wall.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

![]()

Fort Vancouver, reconstructed wall.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

![]()

Chief Factor's house, restored, 1976.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi75125

Related Entries

-

![Buffalo Soldiers at Vancouver Barracks]()

Buffalo Soldiers at Vancouver Barracks

For thirteen months beginning in 1899, a company of 103 soldiers from t…

-

![Concomly (1765?-1830?)]()

Concomly (1765?-1830?)

Of the several Chinook men called Concomly at one time or another, the …

-

![Fort George (Fort Astoria)]()

Fort George (Fort Astoria)

Fort George was the British name for Fort Astoria, the fur post establi…

-

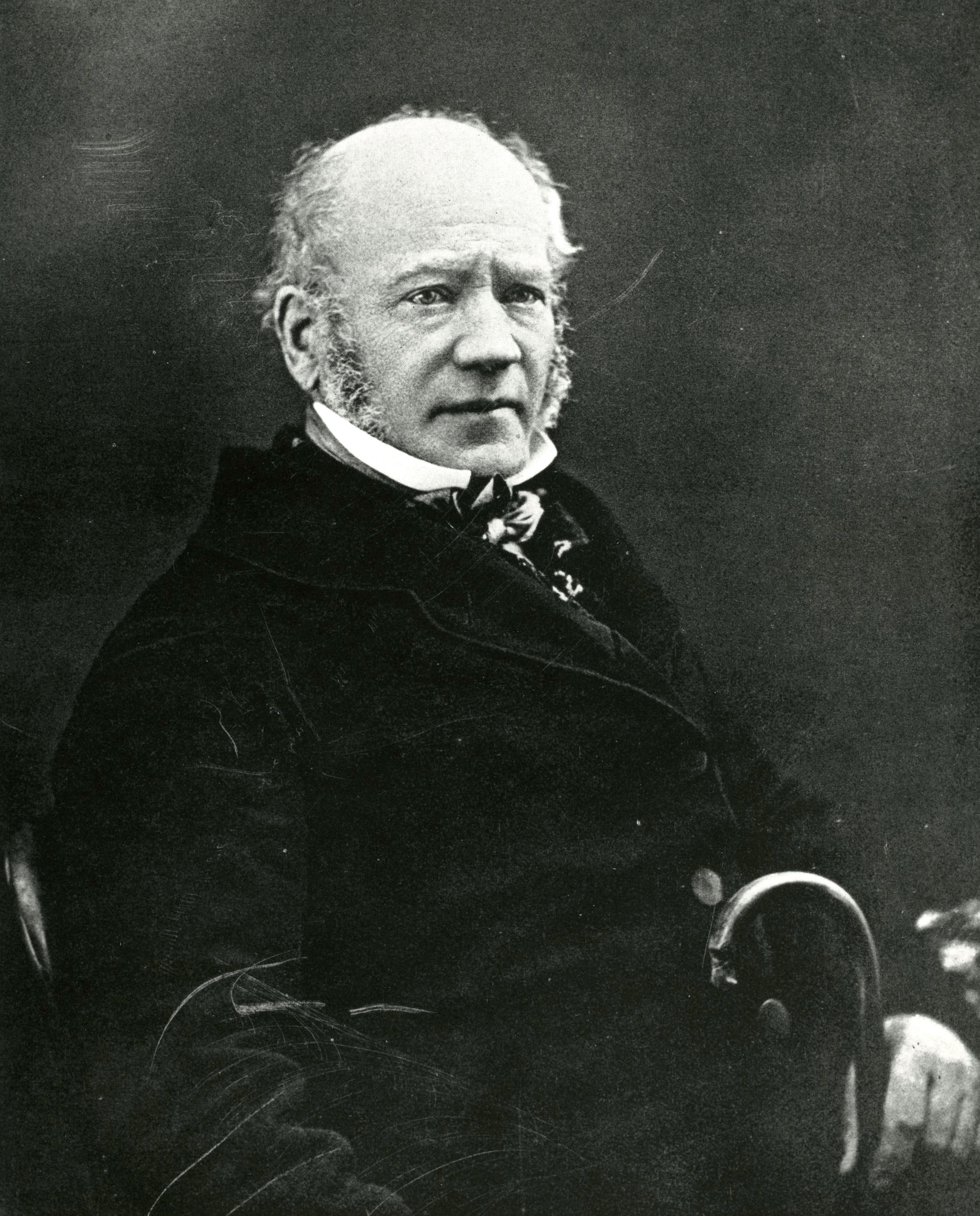

![George Simpson (1786?-1860)]()

George Simpson (1786?-1860)

The highest-ranking officer of the Hudson's Bay Company in North Americ…

-

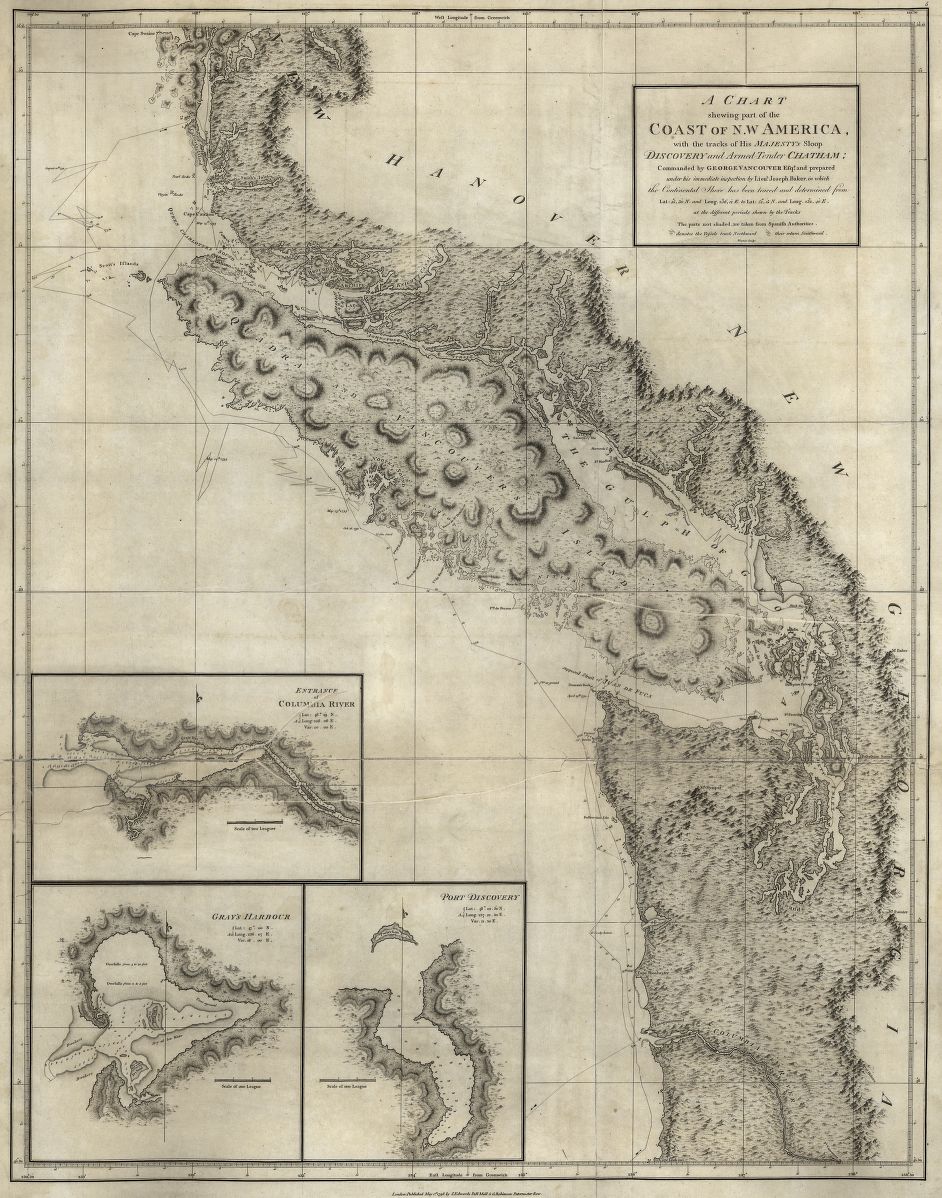

![George Vancouver (1757-1798)]()

George Vancouver (1757-1798)

The role George Vancouver played in Oregon history is tangential, yet i…

-

![Hawaiians in the Oregon Country]()

Hawaiians in the Oregon Country

Native Hawaiians were among the earliest outsiders in present-day Orego…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

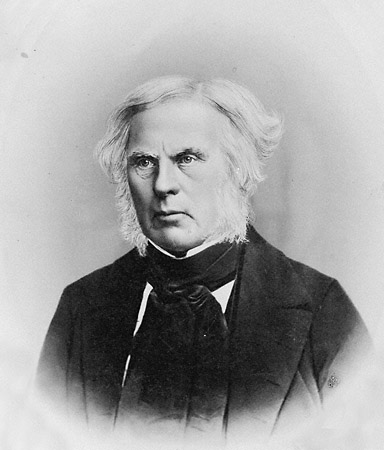

![John McLoughlin (1784-1857)]()

John McLoughlin (1784-1857)

One of the most powerful and polarizing people in Oregon history, John …

-

![McLoughlin House Unit of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site]()

McLoughlin House Unit of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site

One of the grandest and most elaborate homes in Oregon when it was buil…

-

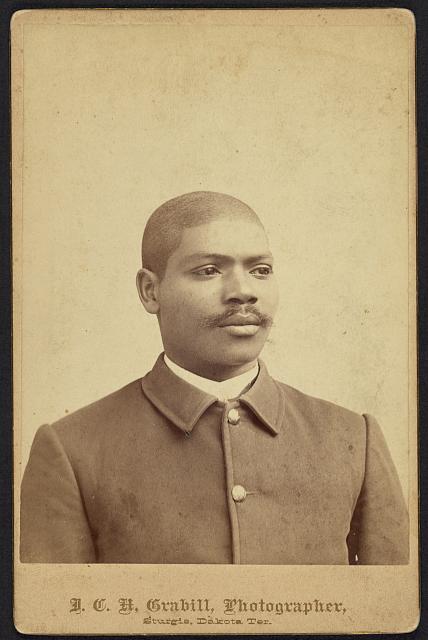

![Moses Williams (1845-1899)]()

Moses Williams (1845-1899)

Born in rural Louisiana in 1845, Moses Williams joined the U.S. Army in…

-

![Oregon Trail]()

Oregon Trail

Introduction In popular culture, the Oregon Trail is perhaps the most …

-

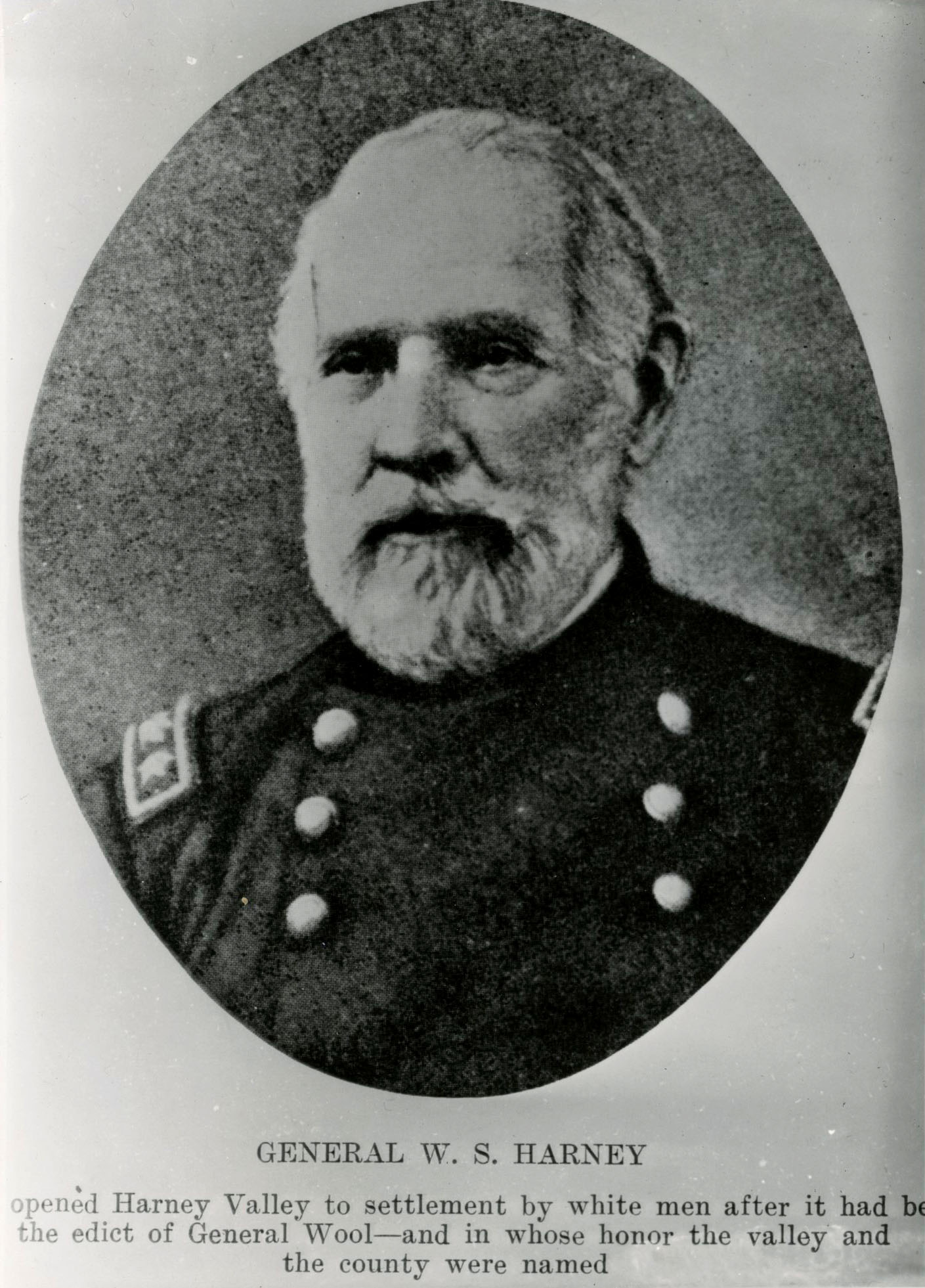

![William Selby Harney (1800-1889)]()

William Selby Harney (1800-1889)

A brash, opportunistic cavalry officer with an explosive temper and a v…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Wilson, Douglas C., and Theresa E. Langford, eds. Exploring Fort Vancouver. Seattle: Univ. of Washington Press, 2011.

Hussey, John A. The History of Fort Vancouver and its Physical Structure. Portland, Ore.: National Park Service & Washington State Historical Society, 1957.

Mackie, Richard Somerset. Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific, 1793-1843. Toronto, Canada.: University of British Columbia Press, 1997.

Gibson, James R. Farming the Frontier: The Agricultural Opening of the Oregon Country, 1786-1846. Seattle: Univ. of Washington Press, 1986.

Ross, Lester A. Fort Vancouver 1829-1860: A Historical Archaeological Investigation of the Goods Imported and Manufactured by the Hudson's Bay Company. Vancouver, Wash.: National Park Service, 1976.

Dunn, John. The Oregon Territory, and the British North American Fur Trade. Philadelphia: G.B. Zieber & Company, 1845. Available online at: https://books.google.com/books?id=ukkOAAAAIAAJ&vq=Vancouver&num=10&pg=PA101#v=snippet&q=Vancouver&f=false .

Merck, Frederick, ed., Fur Trade and Empire: George Simpson’s Journal. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1968.

Wilkes, Charles. Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition, Vol. 4. London, Eng..: Wiley and Putnam,1845. Available online at: https://books.google.com/books?id=MVFHAAAAYAAJ&pg=PR5#v=onepage&q&f=false

Kane, Paul. Wanderings of an Artist Among the Indians of North America. London, Eng.: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts, 1859. Available online at: https://books.google.com/books?id=9_BCAAAAIAAJ&pg=PP1#v=onepage&q&f=false