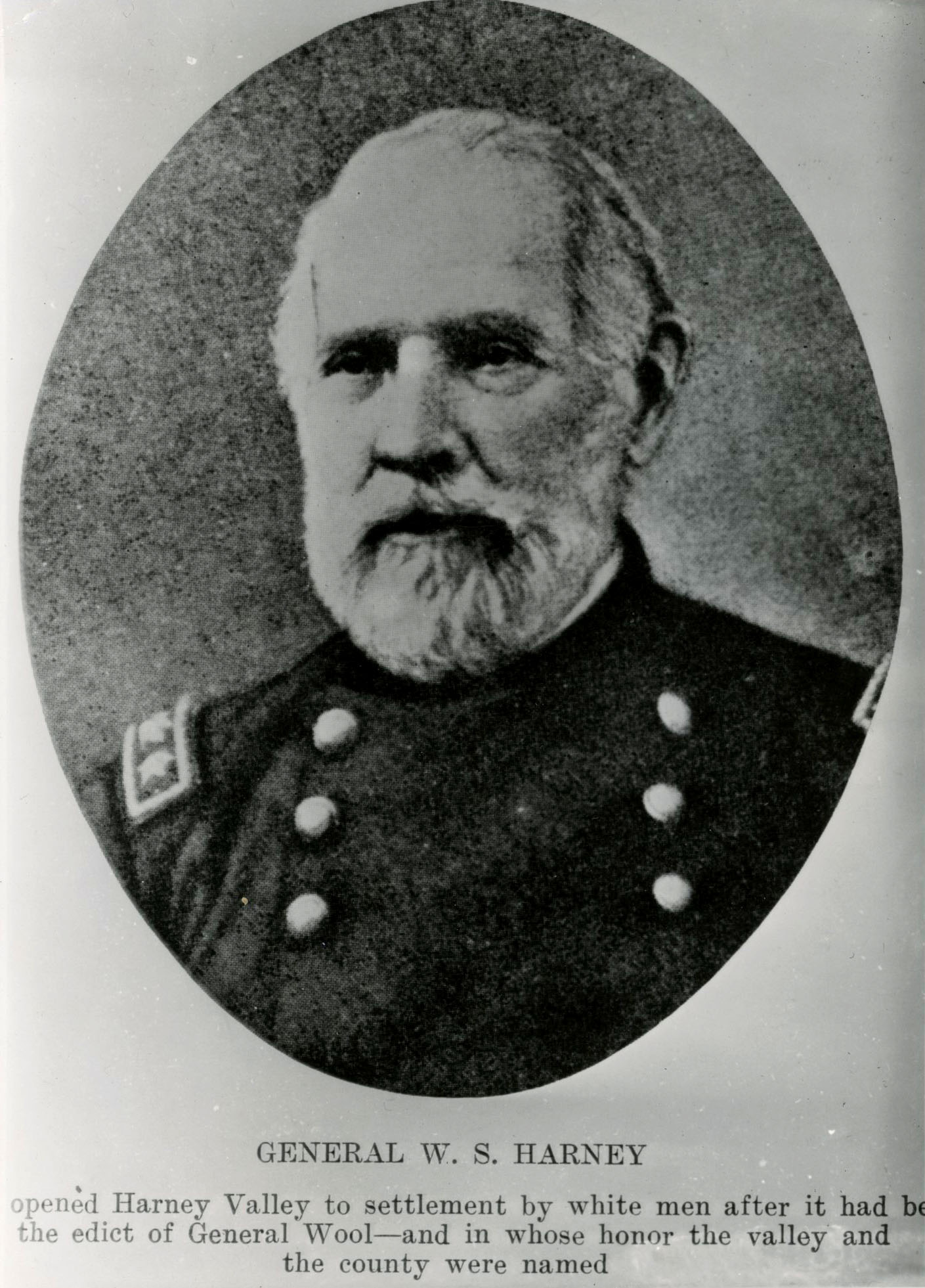

A brash, opportunistic cavalry officer with an explosive temper and a vindictive predilection for conflict with Indians, fellow officers, and foreign powers, Gen. William Selby Harney led the U.S. Army’s Department of Oregon from 1858 to 1860. During his time in Oregon, he expanded military roads and protection while waging war against Native people in Washington Territory and narrowly avoiding war with Great Britain.

Born on August 22, 1800, Harney was a tall, redheaded Tennessean who counted Andrew Jackson as his mentor and Jefferson Davis as his friend. After accepting an officer’s commission in 1819, he used his connections to the Democratic Party to rise quickly through the army’s ranks. Service in the Seminole Wars in the 1830s honed his skill and reputation in savage warfare against Indians, as did later duty in the Mexican War in 1847, frontier service in Texas in the late 1840s and 1850s and the Plains and Midwest in the 1850s, and a return campaign to Florida in 1857. In 1855, at the Battle of Ash Hollow in western Nebraska, soldiers under his command indiscriminately killed Brulé Lakota men, women, and children, earning Harney the sobriquets The Butcher and The Big Chief Who Swears.

Harney did not focus his hair-trigger temper solely on Native peoples. He physically assaulted subordinates, intimidated junior officers, executed deserters in the Mexican War, and bludgeoned to death a family female house slave. Despite—and arguably because of—his reputation, many residents of Oregon and others in the West advocated for his presence, and newspapers welcomed his alacrity and aggressive practice of “rough and ready, sledgehammer warfare.”

Harney's dedication to a martial life left little room for a personal one. He fathered a child, Mary Caroline, through a relationship with Ke-Sho-Ko, a Winnebago woman of mixed ancestry, while posted to Fort Winnebago in the early 1830s, but abandoned them both upon his reassignment. In 1833, in St. Louis, he married Mary Mullanphy and converted to Catholicism. Her family's wealth and status helped further his ambition to rise in the army. He fathered three children with Mary, but after 1850 he would see her only twice. In 1853, she relocated with their children to France, where she died in 1860.

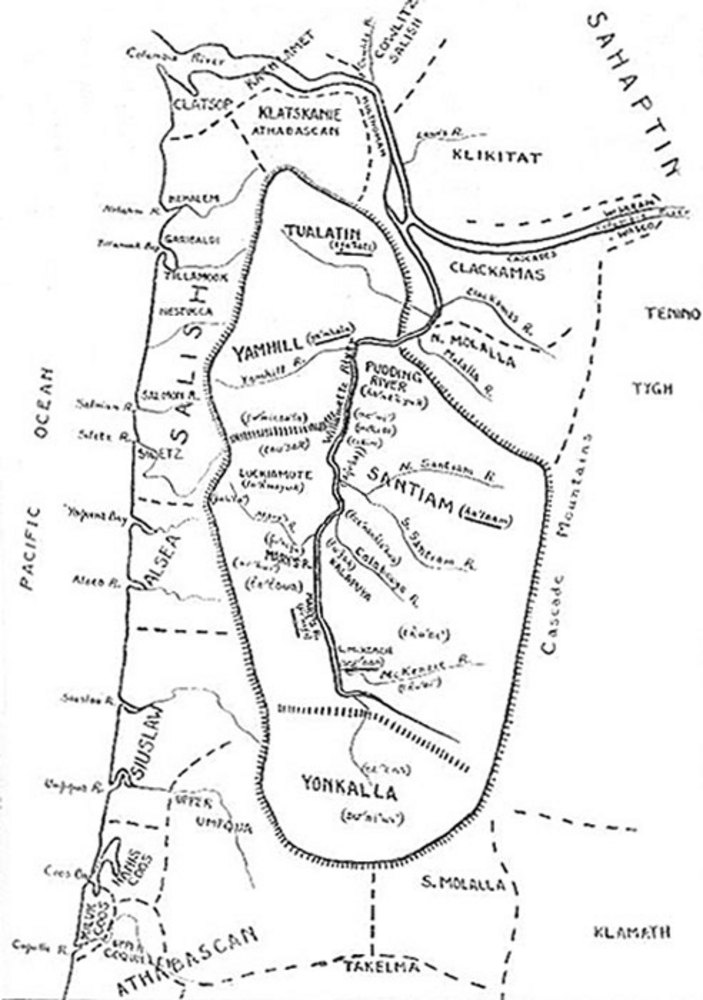

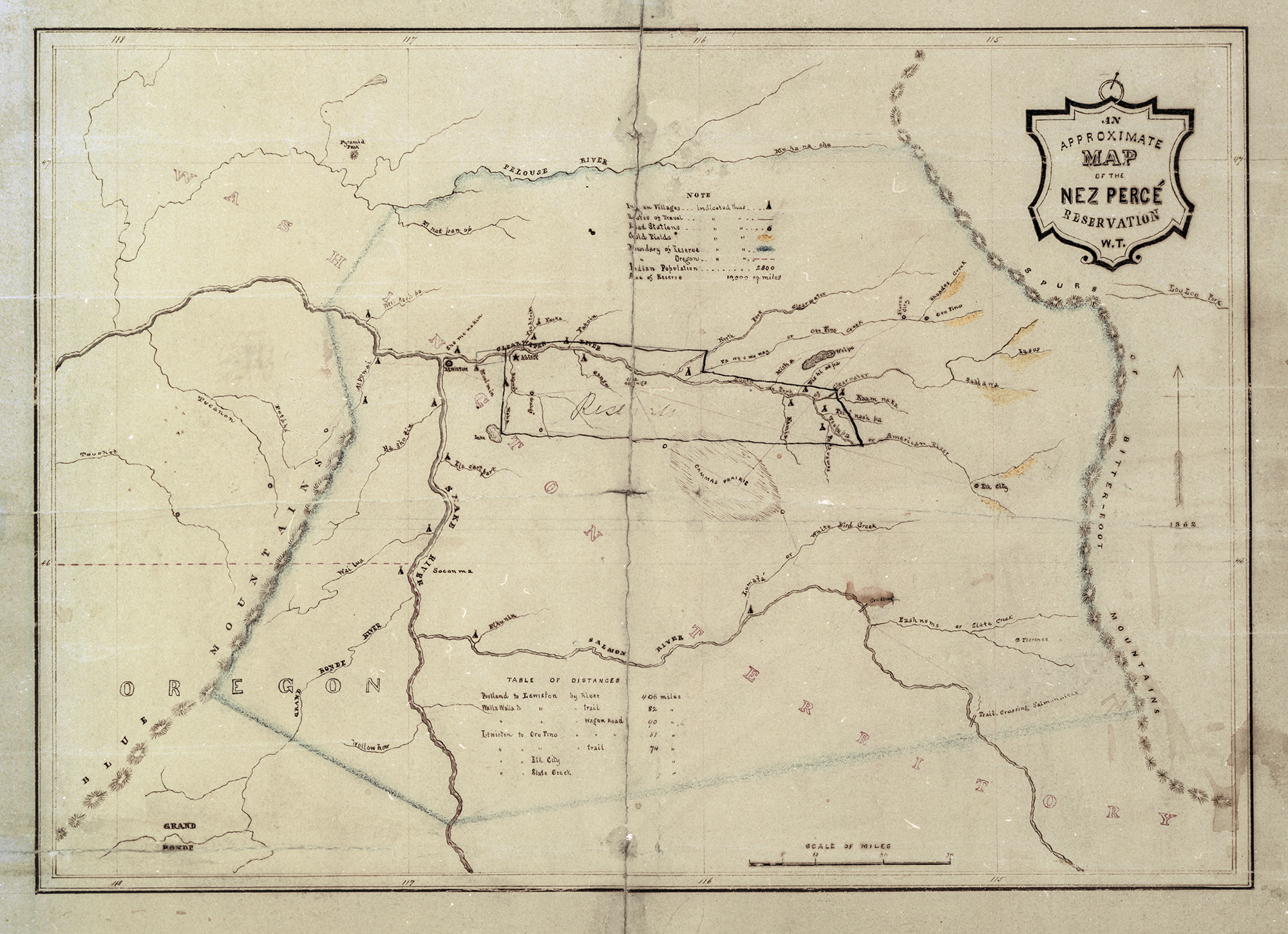

In 1858, in response to conflict provoked by the encroachment of white miners en route to Washington and British Columbia gold fields on traditional Native lands in central Washington Territory, the U.S. Army divided its Pacific Division, creating a new Department of Oregon that encompassed Washington and most of Oregon Territories. Harney was placed in command of the new department and its nearly two thousand soldiers, with a goal of retribution against the Yakama, Palus, Spokane, Coeur d’Alene, and other Northwest peoples who had defeated a column of more than 150 soldiers led by Col. Edward Steptoe.

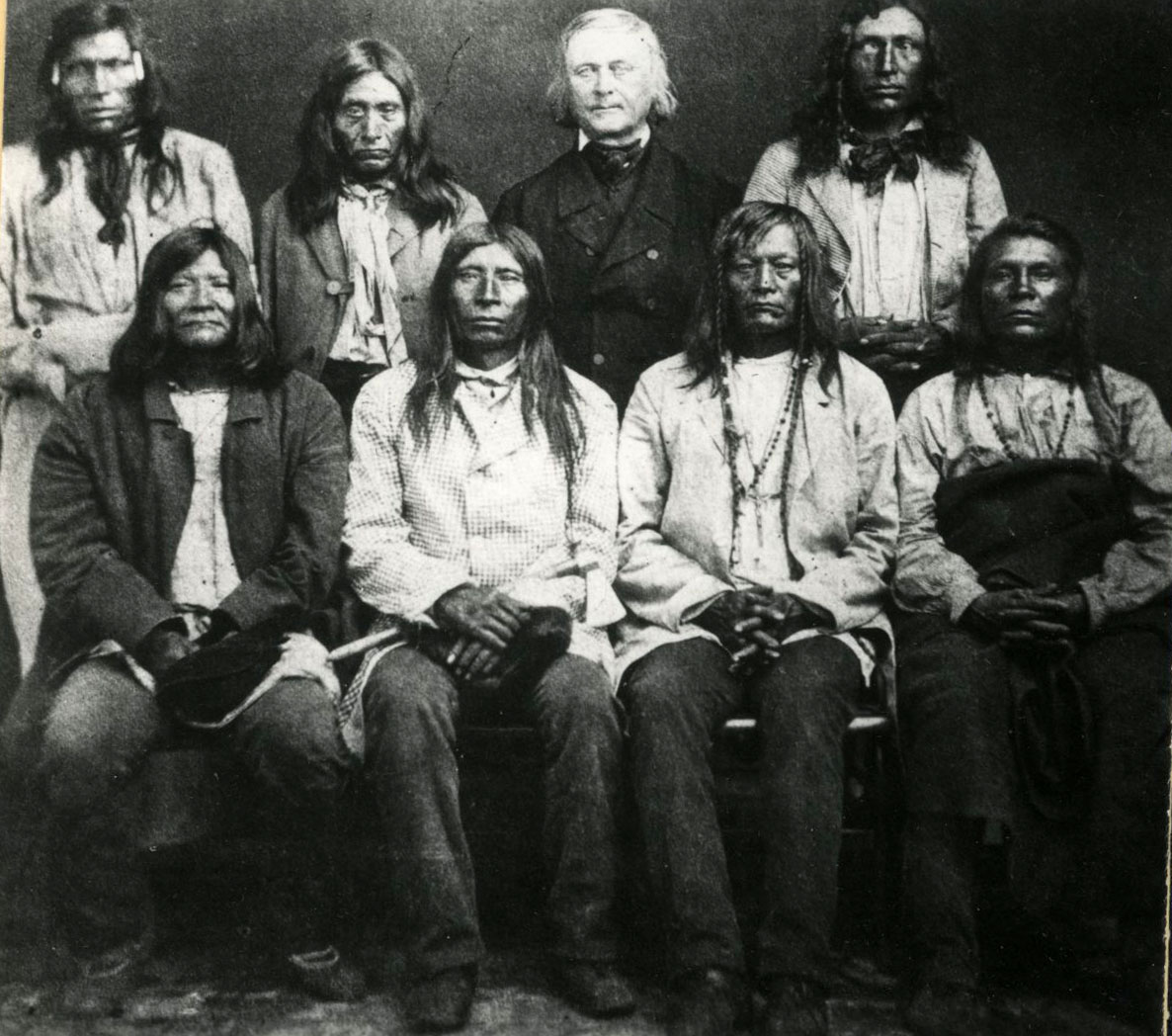

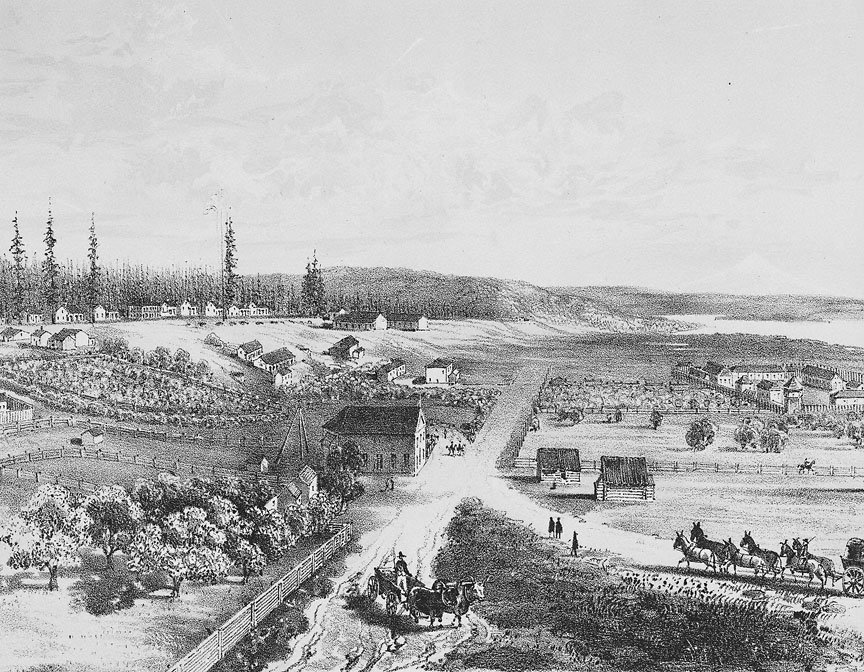

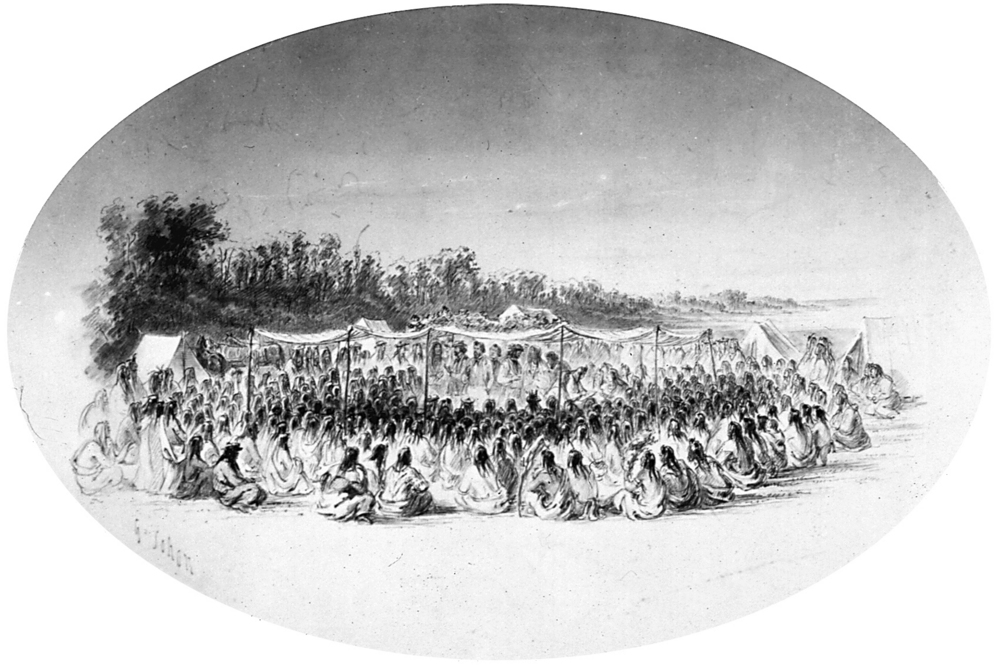

On his way to the department’s headquarters at Fort Vancouver, where he arrived on October 24, 1858, Harney found the fighting over and treaties already prepared. Through his friend Father Pierre-Jean DeSmet, he communicated to tribal leaders his commitment to enforcing the peace. He then opened the country east of the Cascades to whites, assuring resettlers of the army’s protection, and initiated the survey and construction of military roads to improve transportation between the interior and the Willamette Valley. It was a strategy that appealed to settlers but strained relations with the region’s Native peoples.

Harney’s undoing in the Pacific Northwest stemmed from his antagonism of Great Britain, which brought two nations to the brink of war. Following the shooting of a Hudson’s Bay Company’s pig by an American citizen in June 1859, Harney sent troops to occupy San Juan Island, the ownership of which was in dispute and under negotiation. Following the arrival of British warships, he escalated the situation by sending reinforcements and directing a lieutenant to proclaim that the island was U.S. territory. Learning of the crisis, President James Buchanan dispatched Winfield Scott, the army’s commanding general, to the Columbia River, where he chastised Harney and discussed his reassignment. He was relieved of his departmental command on June 8, 1860, and ordered to “report in person to the Secretary of War.” The confrontation was dubbed the "Pig War."

Harney led the Department of the West from St. Louis until he was again relieved of command in 1861 due to his perceived indecision during the Missouri secession crisis. After retiring in 1863, he served with the Indian Peace Commission, and in 1884 he married Mary St. Cyr. Harney died at his home near Orlando, Florida, in 1889, just months after Harney County was named for him. He is the namesake of the Oregon community of Harney, Harney Valley, Harney Lake, and Fort Harney (1867-1880).

-

![]()

William S. Harney.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi4396

-

![]()

Harney's house in Vancouver, Wash., 1908.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 023494

-

![]()

Father de Smet with tribal leaders he persuaded to surrender to Harney, c.1858.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi624

Related Entries

-

![Creation of Washington Territory, 1853]()

Creation of Washington Territory, 1853

On August 14, 1848, Congress created Oregon Territory, a vast stretch o…

-

![Fort Vancouver]()

Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver, a British fur trading post built in 1824 to optimize th…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

![Kalapuya Treaty of 1855]()

Kalapuya Treaty of 1855

The treaty with the Confederated Bands of Kalapuya (1855) is the only r…

-

![Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon]()

Native American Treaties, Northeastern Oregon

After American immigrants arrived in the Oregon Territory in the 1840s,…

-

![Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855]()

Walla Walla Treaty Council 1855

The treaty council held at Waiilatpu (Place of the Rye Grass) in the Wa…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaties]()

Willamette Valley Treaties

From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tri…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Adams, George Rollie. General William S. Harney: Prince of Dragoons. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

Ball, Durwood. Army Regulars on the Western Frontier, 1848-1861. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2001.

Schlicke, Carl P. General George Wright: Guardian of the Pacific Coast. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Shine, Gregory P. "An Indispensable Point": A Historic Resource Study of the Vancouver Ordnance Depot and Arsenal, 1849-1882. Vancouver, Wash.: National Park Service, 2008.

Vouri, Michael. The Pig War: Standoff at Griffin Bay. Friday Harbor, WA: Griffin Bay Bookstore, 1999.