The Hanis (hanıs) people lived in villages along Coos Bay, Coos River, and Tenmile Lake on the Oregon Coast. Miluk-speaking villages were on lower Coos Bay, and both Hanis and Miluk were almost universally lumped together in records created by early explorers and settlers, where they were sometimes referred to as the Kowes or Koos tribe. Their culture and political structure were similar to the Miluk and Quuiich (Lower Umpqua), their immediate neighbors. Each village had a headman who adjudicated disputes in the village and between villages and helped ensure that residents had the resources they needed. The headman also helped host or arrange events that included dances, games, ceremonies, and trade with other tribes.

The Hanis and Miluk peoples lived in an estuarine and coastal environment that provided diverse resources for food, medicine, and material culture. Rivers and the sea provided an abundance of fish, shellfish, marine mammals, and migratory waterfowl, and the land provided game and edible plants. Local people carefully tracked the times of fish runs, the best times for hunting deer and elk, and the most favorable times to burn in order to maintain good browse for game and encourage the growth of plants favored for food and basketry.

The permanent villages of the Hanis were concentrated along the bay and its sloughs, and the people had seasonal upriver fishing camps on Coos River and the Millicoma River, known in Hanis as k’ʊgwič. Some villages as far upriver as present-day Allegany were occupied year round. The modern name Millicoma for the South Fork Coos River is an accidental transposition of the Hanis name for the river, where many Miluk families had seasonal fishing rights. The northernmost Hanis villages were in skæ-ıč (skanič is the quuiich version of the name), south of Tenmile Lake. The Lower Umpqua people lived on North Tenmile Lake, a meeting place for Coos Bay and Lower Umpqua villagers to gather wapato (Sagittaria latifolia) tubers.

The large permanent houses built by the Hanis were semi-subterranean structures with walls and roofs made of red-cedar planks and support posts that were usually Douglas-fir. The walls and floors were covered with tule (Schoenoplectus sp.) mats. Twined baskets were so important that in Hanis there are more than two dozen names for types of baskets. Their uses range from fish traps and mats to storage and clothing.

At certain times of the year, many Hanis traveled to trade. People from Coos Bay (both Hanis and Miluk) and Nasomah (Lower Coquille) met annually in the late spring near present-day Whiskey Run to gather camas and brodiaea harvest lilies. Some traveled east to Camas Valley. There was also trade from the Columbia River region and northern California. Through trade, Hanis obtained items such as high-prow canoes, obsidian, grey pine nuts (Pinus sabiniana) for beads, dentalia, and clamshell disc beads.

The Hanis language is similar in many respects to Miluk, which was spoken on lower Coos Bay. Anthropologist Melville Jacobs concluded that the two languages were “perhaps as close as, or, to use a rough analogy, closer than Dutch and High German.” The Hanis language is classified by many linguists as part of the Coast Oregon Penutian group, which includes two Coosan languages and the Siuslawan and Alsea-Yaquina languages to the north. The Salish traits in these languages may be due to centuries of encounters with Salish-speaking communities.

Treaties and Removal

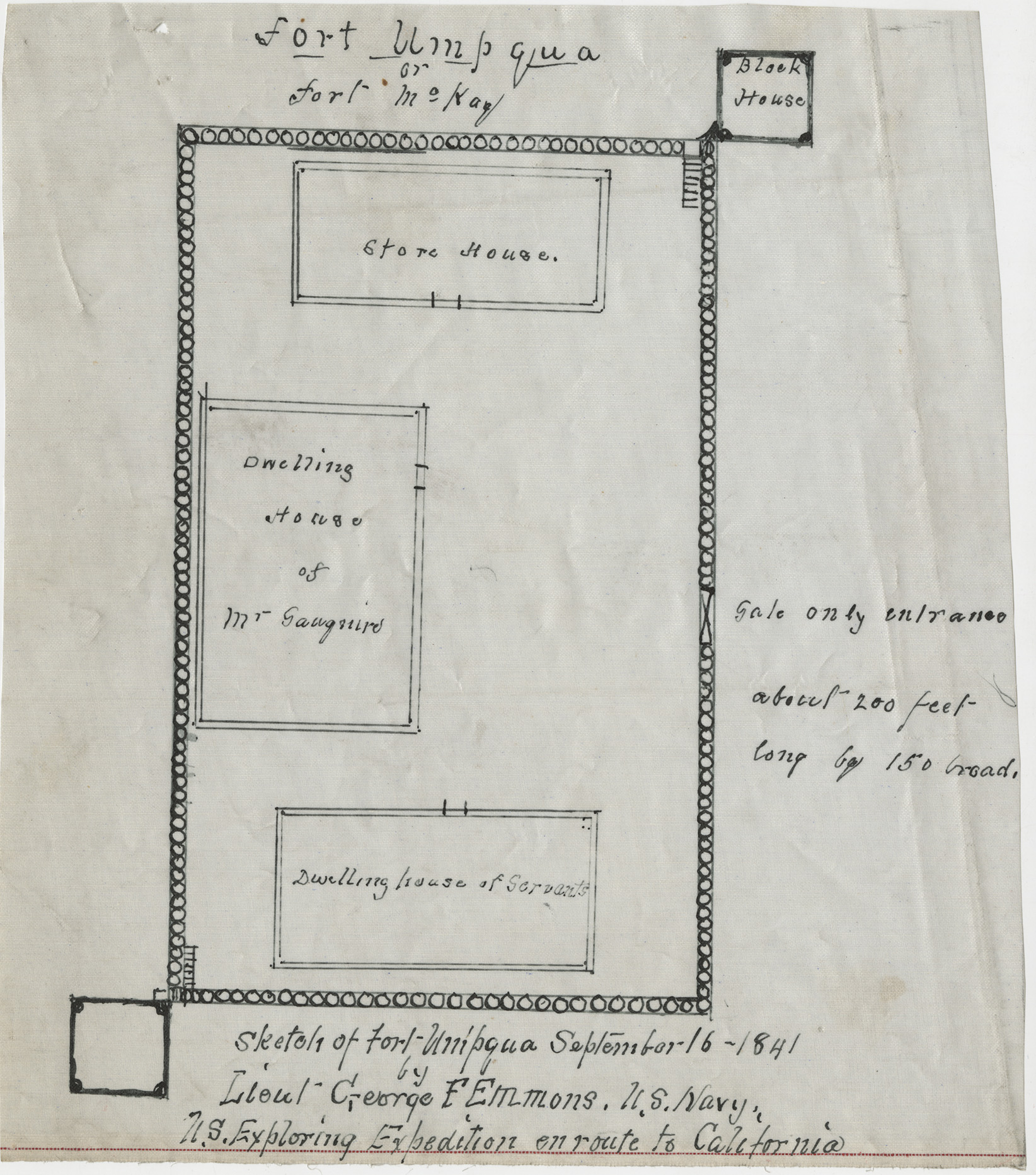

The first known sustained encounters with Europeans for Hanis and their neighbors were in the early nineteenth century. Jedediah Smith’s ill-fated trapping expedition passed through Coos Bay in 1828, and parties of fur traders affiliated with the Hudson’s Bay Company occasionally traveled as far south as Coos Bay and the Umpqua Valley. In 1836, the Hudson’s Bay Company established Fort Umpqua, a small trading post where Elkton is today. Encounters tended to be sporadic until the 1850s, when white settlers became more interested in the region for its potential as a harbor and the nearby thick stands of timber and coal deposits.

Encounters with explorers introduced several diseases that the Native people had no immunity to—influenza, measles, whooping cough, and tuberculosis among many others—but one of the deadliest was smallpox. Exact dates of outbreaks in the Coos Bay region in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries is not well documented, but the disease likely spread from populations to the north and south, and outbreaks occurred in around 1824, 1836, and 1853. According to oral tradition, the Hanis people of Tenmile Lake were completely wiped out by smallpox except for one older woman.

On January 1, 1852, the schooner Captain Lincoln ran aground on Coos Bay’s North Spit. The crew set up camp, which the stranded crew called Camp Castaway, and stayed on the spit for four months until the crew could be picked up. In the meantime, they traded frequently with Native people. One of the castaways, Henry Baldwin, wrote about a “Chief Hanness,” who would have been the chief of hanısič (Hanisiich) village across the bay from the camp. He and his people were frequent visitors. Word of the bay soon spread to non-Natives, and in 1853 resettlers organized a group from Jacksonville to attempt to take land claims in Coos Bay—a venture that was technically illegal under American law, since no treaty had been negotiated for land cessions.

In 1855, the United States sent General Joel Palmer to negotiate a treaty with the coastal tribes. Among the signers were representatives of the Hanis. The treaty was never ratified. A year later, when war heated up between resettlers and southern Oregon tribes, many Coos Bay people were removed by the federal government. Most of them, both Miluk and Hanis, were forced to go to Fort Umpqua, a military fort that existed briefly at the mouth of the Umpqua River. Indian Agent J. B. Sykes began removal of the Coos Bay and Lower Umpqua people from the fort to the Alsea Sub-Agency at Yachats in September 1859.

Since the Treaty of 1855 was never ratified, the federal government did not feel obligated to supply goods promised in the treaty, such as materials for a sawmill, schools, and even food. The years at the subagency were marked by inadequate supplies. Some of the women were allowed to remain in southern Oregon if they were married to white men, and many of those families sheltered relatives who resisted removal or escaped from the reservations. Conditions at the Alsea Sub-agency were hard, and more than half the people imprisoned there died, many from starvation or illness.

When the Alsea Sub-agency was closed in 1876, many Hanis, Miluk, and Lower Umpqua people chose to move back to their ancestral homelands instead of to the Siletz agency. Many eventually took up allotments on the Siuslaw and Umpqua Rivers and at Coos Bay. An intertribal community of Hanis, Miluk, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw people formed around the North Fork Siuslaw River, with some families still possessing Indian allotments.

Land Claims, Termination, and Restoration

Although the Treaty of 1855 had not been ratified, the Native people had not forgotten it or that they had never received any money for their lands. The Coos Bay, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw people worked together to pursue land claims. Meetings were held as early as 1890 to discuss pursuing land claims, but it wasn't until 1917, when more consistent meetings were held, that representatives were sent to Washington, D.C., to lobby Congress to sue the U.S. government. It took many years, but on February 23, 1929, Congress passed a bill authorizing a suit for land claims. In 1931, in a courthouse in Empire (now part of Coos Bay), several tribal Elders and a few pioneers gave their testimony regarding the lands originally held by the Coos Bay (Hanis and Miluk), Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw tribes. On May 2, 1939, the Court of Claims issued a ruling against the tribes, discounting the oral testimony of tribal Elders because they had a financial stake in the outcome of the case.

Throughout the 1940s and early 1950s, the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw pursued appeals to the Indian Claims Commission. The ICC again ruled against the tribes on July 11, 1952. That event was soon followed by hearings on terminating the federal recognition of tribal governments. The Confederated Tribes opposed the policy but ultimately were included in Public Law 588, the bill passed in August 1954 that terminated western Oregon Tribes.

The Tribes then focused on restoration, which was successful for the Confederated Tribes of Siletz in 1977 and the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw in 1984. Today, descendants of the Hanis are enrolled predominantly with the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz.

-

![]()

Lottie Jackson Evanoff (Hanis Coos), daughter of Chief Jackson, 1940.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 011300

-

![]()

Map of Native homelands in Western Oregon.

Courtesy Atlas of Oregon, 2nd ed., University of Oregon Press, 2001 -

![]()

Tribal Hall of the Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw, under construction, 1940-1949.

Courtesy Oregon State University Libraries -

![]()

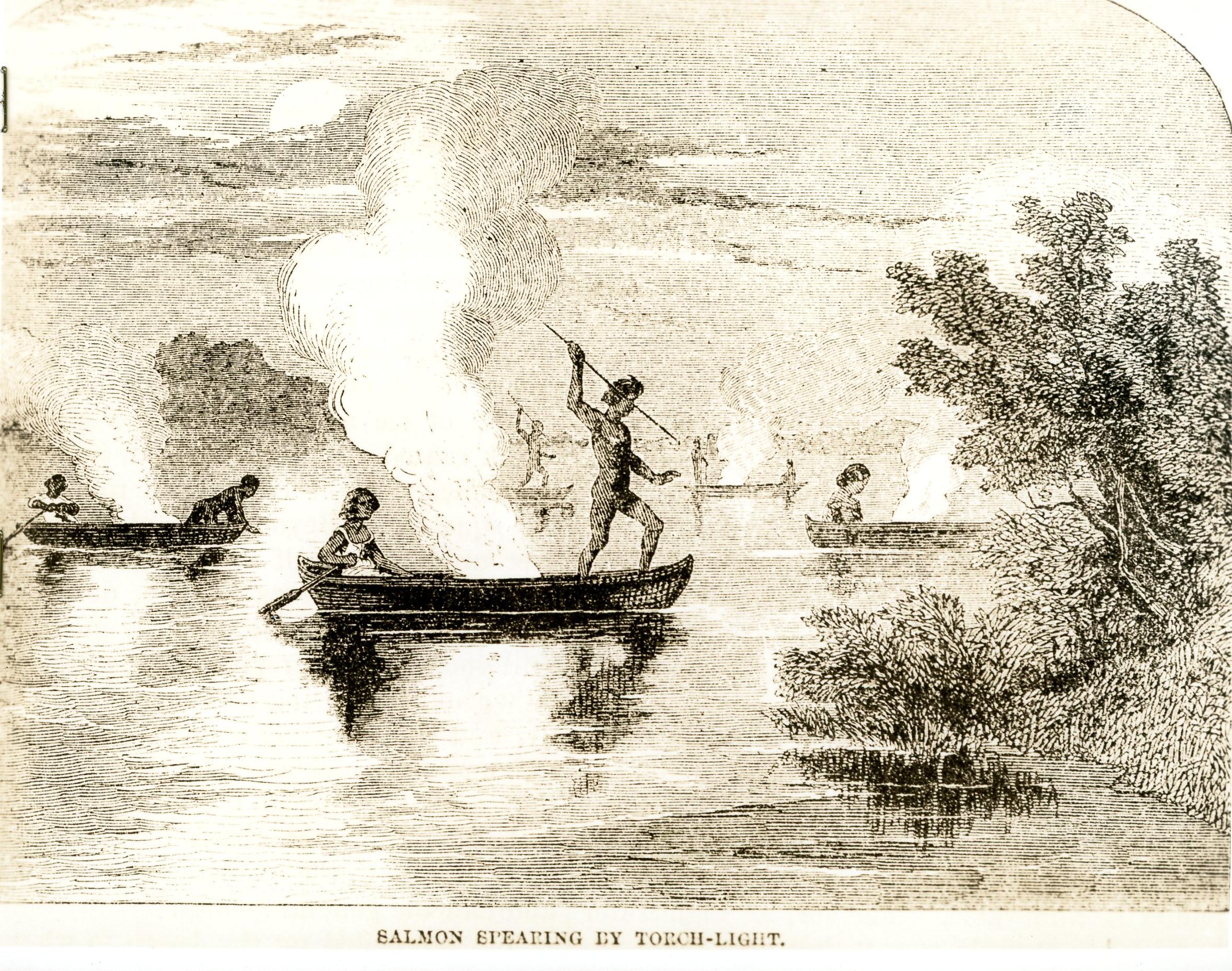

Salmon Fishing on Coos Bay, Harper's Monthly, 1855.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 24446, photo file 282

-

![]()

Tenmile lakes, Coos Bay.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, photo file 282

-

![]()

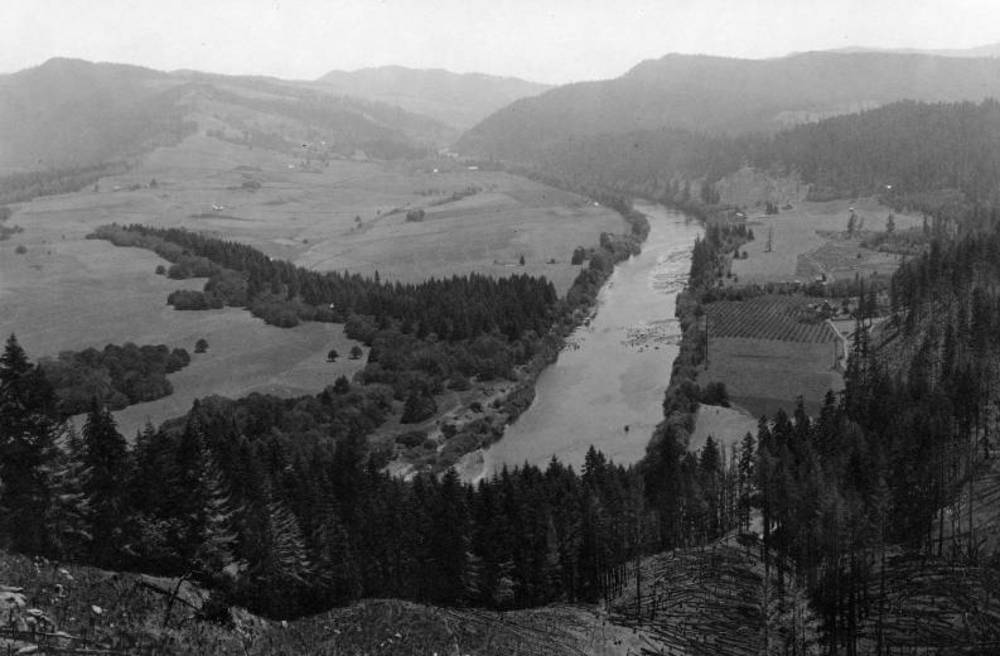

Coos River.

Courtesy University of Oregon Libraries -

![]()

Coos Head.

Oregon Historical Society Research Library, 14866, photo file 282

-

![]()

Sketch of Fort Umpqua by Lt. Emmons, 1841.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., mss171 19WGdJd

Related Entries

-

![Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation]()

Alsea Subagency of Siletz Reservation

In September 1856, Joel Palmer, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs fo…

-

![Coos Bay]()

Coos Bay

The Coos Bay estuary is a semi-enclosed, elongated series of sloughs an…

-

![Coquille]()

Coquille

The city of Coquille (pronounced ko-KEEL), a wood-products manufacturin…

-

![Fort Umpqua (HBC fort, 1836-1853)]()

Fort Umpqua (HBC fort, 1836-1853)

Fort Umpqua was a small but important post in the Hudson’s Bay Company’…

-

![Joel Palmer (1810–1881)]()

Joel Palmer (1810–1881)

Joel Palmer spent just over half of his life in Oregon. He first saw th…

-

![Miluk]()

Miluk

Miluk was one of two related languages spoken by people known collectiv…

-

![Termination and Restoration in Oregon]()

Termination and Restoration in Oregon

Termination Of the federal-Indian policies introduced to American Indi…

-

![Umpqua River]()

Umpqua River

The Umpqua River, approximately 111 miles long, is a principal river of…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Beck, David R. M. Seeking Recognition: The Termination and Restoration of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians, 1855–1984. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Beckham, Stephen Dow. “Lonely Outpost: The Army's Fort Umpqua.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 70.3 (1969): 233–57.

Frachtenberg, Leo. Coos Texts. Columbia University Contributions to Anthropology, vol. 1 (series). New York: Columbia Univ. Press, 1913.

Jacobs, Melville. Coos Narrative and Ethnologic Texts. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1939.

Jacobs, Melville. Coos Myth Texts. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1940.

Phillips, Patricia Whereat. Ethnobotany of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2016.

Schwartz, E. A. 1991. “Sick Hearts: Indian Removal on the Oregon Coast, 1875-1881.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 92 (1991): 228-64.