Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two decades in the early nineteenth century the British Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) dominated the region’s social, economic, and political life while ensuring profit to its shareholders. This quest for profit—achieved through the pioneering extraction of the Pacific Northwest’s bountiful furs, forests, and fish and through appropriation of aboriginal lands for large-scale farming—laid the foundation for later American economic successes and a notable portion of Oregon’s economy today.

Established by royal charter in 1670, England’s King Charles II granted the corporation—originally recognized as “the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson’s Bay”—exclusive English rights as “absolute lords and proprietors” to all lands within the watersheds of Hudson’s Bay and the Hudson’s Bay Straits. Controversial for decades, the breadth of rights conferred by the charter over this area—called Rupert’s Land—included full governmental authority to create and enforce laws in the territory, along with sole control over natural resource extraction and commerce. It also banned English subjects from unauthorized access or trade under threat of punishment from the crown. Increasingly, groups of free traders disputed the legitimacy of this monopoly, and a rival company, the Montreal-based North West Company (NWC), formed in 1787. The NWC challenged the HBC throughout Rupert’s Land and beyond, establishing a network of trade that directly competed with the HBC and led to open hostility and war.

Both the New York-based Pacific Fur Company (PFC) and the NWC experimented unsuccessfully with the fur trade in Oregon, but it was not until the forced merger of bitter rivals NWC and HBC in 1821—and the subsequent conveyance of exclusive British trading rights to the HBC for lands in the Pacific Northwest jointly occupied by Britain and the United States—that the HBC entered the region. Unlike the PFC, which recognized the value of the area’s resources but was unable to capitalize on them, NWC conventional wisdom suggested that the lands comprising the Columbia Department (roughly defined as the Columbia River watershed) promised no profit and would serve, at best, as a buffer to protect the fur-rich New Caledonian lands from American encroachment; but the political ramifications of abandoning the Oregon Country also loomed large.

Explorations by HBC Governor George Simpson and others—including Alexander Ross, a veteran of the PFC, NWC, and HBC—confirmed that possession of the land served “to check the opposition” of expansionist Americans and Russians and suggested the potential for significant profit through the self-sufficiency of HBC posts.

Subsequent visits throughout the Department, stimulated by the extension of a watershed joint occupancy agreement with the United States that protected the HBC’s dominating interests and justified greater investment in the Oregon Country, led Simpson to reorganize the Department posts and maritime trade operations around a newly constructed headquarters—Fort Vancouver, which would become the region's center of EuroAmerican influence. At the fort, he placed Dr. John McLoughlin in sole charge of all HBC interests west of the Rocky Mountains, including the coastal shipping trade and interests in California and Hawaii.

Rather than supply its posts overland from Hudson Bay or Montreal, McLoughlin managed a system of direct shipping between London and Fort Vancouver, linking global trade directly and regularly to the Oregon Country. He also set in motion Simpson’s vision of self-sufficiency, reaping impressive harvests from fire-managed prairies, plains, and other land ripe for agricultural production near HBC posts to counter Simpson’s mandated reductions in imported food. In addition to furs, McLoughlin diversified the company’s interests to include the production and export of lumber, salted salmon, beef, and grain.

At the heart of the HBC’s operation—and its success in ensuring profit to its shareholders—lay its employees. The HBC organized its human resources through a strict hierarchy that reflected its British roots, with proprietors at the top (and largely in Britain), followed by commissioned officers (including the chief factors, chief traders, and clerks), and a working class of servants and charges (including fur trappers, voyageurs, farmers, and various tradesmen) known as engagés due to their required employment contract or engagement for services.

While most of the commissioned officers hailed from Britain, the engagés reflected a much more expansive ethnic diversity. In addition to Orkney Islanders and French Canadians, working-class employees of Native American ethnicity abounded, as did those with a mixture of Native American and European heritage, known as Métis. At Fort Vancouver, for example, HBC and Catholic Church records note the presence of more than thirty Native American groups from the Pacific Northwest, along with Cree and Iroquois from other parts of North America. Natives of Hawai’i—known as Sandwich Islanders or Kanakas—also served important roles and dominated the HBC’s working class in the waning years of the fur trade. Americans named the HBC employee village at Fort Vancouver Kanaka Village because of their prevalence. The HBC’s operational structure, including employee contracts, food rations, and payment through credit at HBC stores, connected those working-class employees as did the fur-trade language Chinuk Wawa.

This ethnic diversity developed into a unique North American fur-trade culture and permeated all aspects of the HBC ‘s North American operations. Describing a typical trek on the Columbia River, Simpson noted that his boat carried “as curious a muster of races and languages as perhaps had ever been congregated within the same compass in any part of the world. Our crew of ten men contained Iroquois, who spoke their own tongue; a Cree halfbreed of French origin, who appeared to have borrowed his dialect from both his parents; a North Briton, who only understood the Gaelic of his native hills; Canadians who, of course, knew French; and Sandwich Islanders, who jabbered a medley of Chinook and their own vernacular jargon. Add to all this that the passengers were natives of England, Scotland, Russia, Canada, and the Hudson’s Bay Company’s territories; and you have the prettiest congregation of nations, the nicest confusion of tongues, that has ever taken place since the days of the tower of Babel.”

Politically, the HBC represented the region’s early de facto government and drove the economics of supply and demand through its manipulation of prices and inventory. Its policy of discouraging American settlement north of the Columbia River, its lack of competition, the relative cultural diversity of its employees, and its status as a British company led many Oregon Trail emigrants to openly resent and oppose it, notwithstanding the humanitarian aid the HBC offered many of them. It also permanently transformed the economies of many Native American tribes, valuing their fur trapping and trading at company posts over other traditional activities.

Despite being located on land that the HBC believed would become part of the United States, HBC activities and posts in present-day Oregon served important roles in the company’s strategy for success. As early as 1827, Simpson had directed McLoughlin to “push the Trade south of the Columbia and improve our Establishments in that quarter.” The fur-desert policy of Peter Skene Ogden’s Snake Country expeditions through southeast Oregon brought the company economic and political profit by trapping out many fur-bearing animals and leaving the area barren and unattractive to American trappers. Additionally, HBC reopened Fort George (in present-day Astoria) as a small post that aided the maritime and salmon trades, and built Fort Umpqua (near present-day Elkton) to strategically link the Willamette Valley corridor with southern routes and to supply the HBC’s Southern Party fur brigades that ventured into California and to the east.

As the Willamette Valley grew in population and influence, HBC opened a mercantile store in Oregon City to serve the growing needs of American settlers as well as retired HBC employees who established communities such as Champoeg in French Prairie. To HBC, these assets represented tangible capital interests that would require compensation through any treaty process, and all operated until about 1848.

The Oregon Treaty of 1846 ceded lands, including all of present-day Oregon, to the United States, and the HBC soon began negotiations to divest its affected property and rights. Not until 1869 was the matter resolved, when an arbitrator awarded the HBC $450,000 for all its rights and claims in the United States. Today, NRDC Equity Partners, an American corporation, owns the HBC and its more than 600 stores in Canada known as The Bay, Zellers, and Home Outfitters.

-

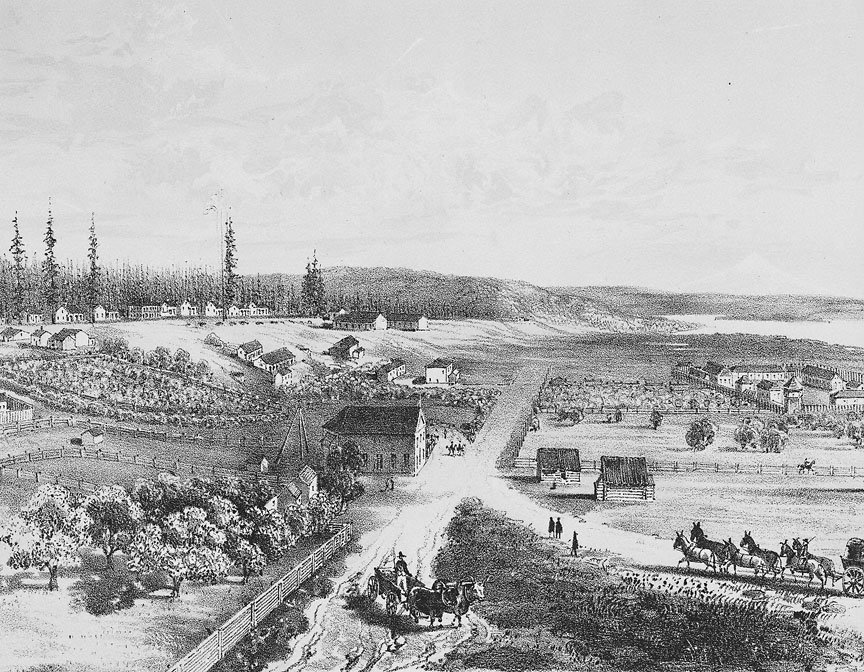

![Fort Vancouver, 1854]()

Fort Vancouver, 1854.

Fort Vancouver, 1854 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., CN008519

-

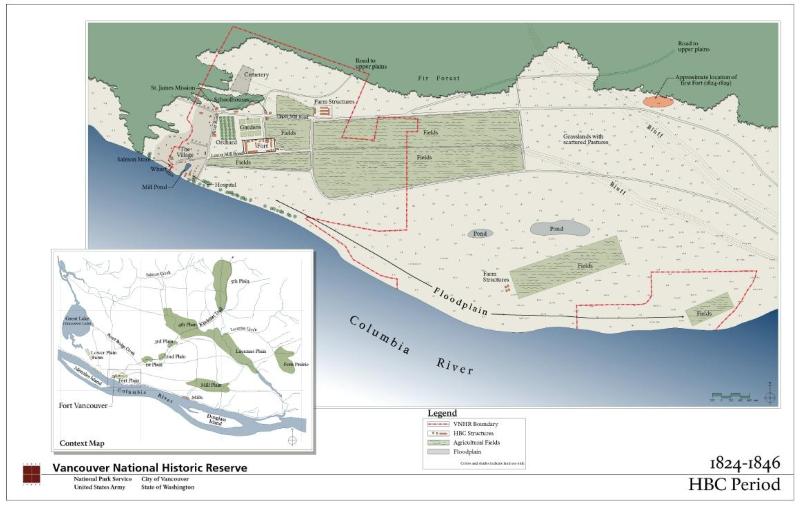

![Map of the Fort Vancouver area during HBC period, 1824-1846]()

Map of the Fort Vancouver area during HBC period, 1824-1846.

Map of the Fort Vancouver area during HBC period, 1824-1846 Courtesy National Park Service

-

![Last standing HBC building in Fort Nisqually, 1906]()

Fort Nisqually, 1906.

Last standing HBC building in Fort Nisqually, 1906 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., neg. no. 52429

-

![Sketch of Fort Vancouver by H.J. Warre, c. 1845]()

Sketch of Fort Vancouver by H.J. Warre, c. 1845.

Sketch of Fort Vancouver by H.J. Warre, c. 1845 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi83437

-

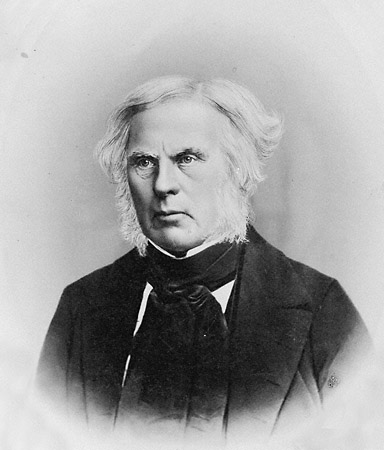

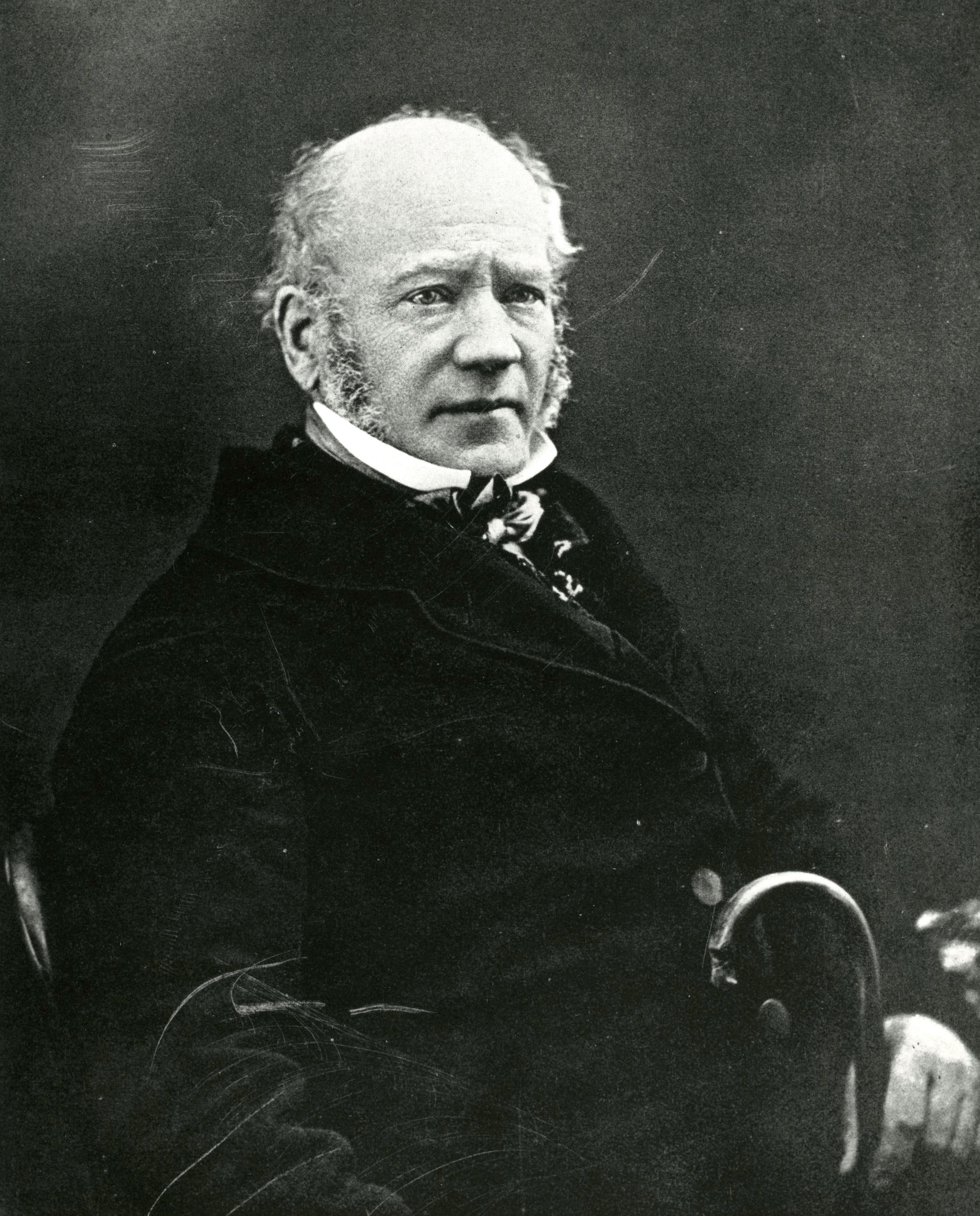

![John McLoughlin]()

John McLoughlin.

John McLoughlin Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi067763

-

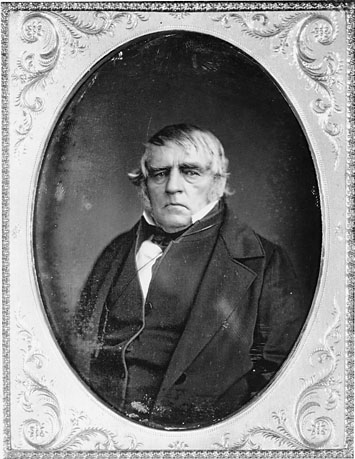

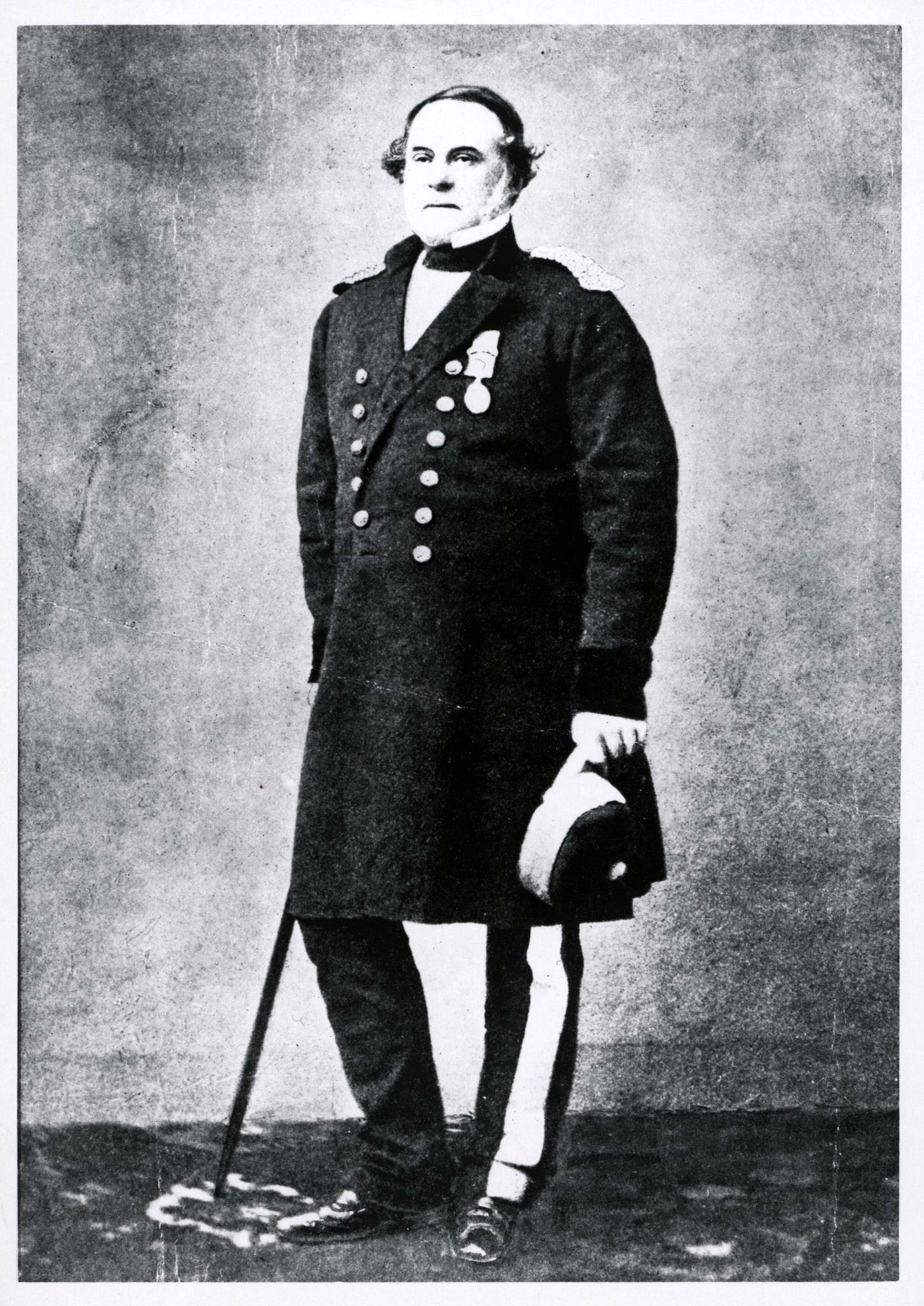

![Peter Skene Ogden]()

Peter Skene Ogden.

Peter Skene Ogden Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi707

-

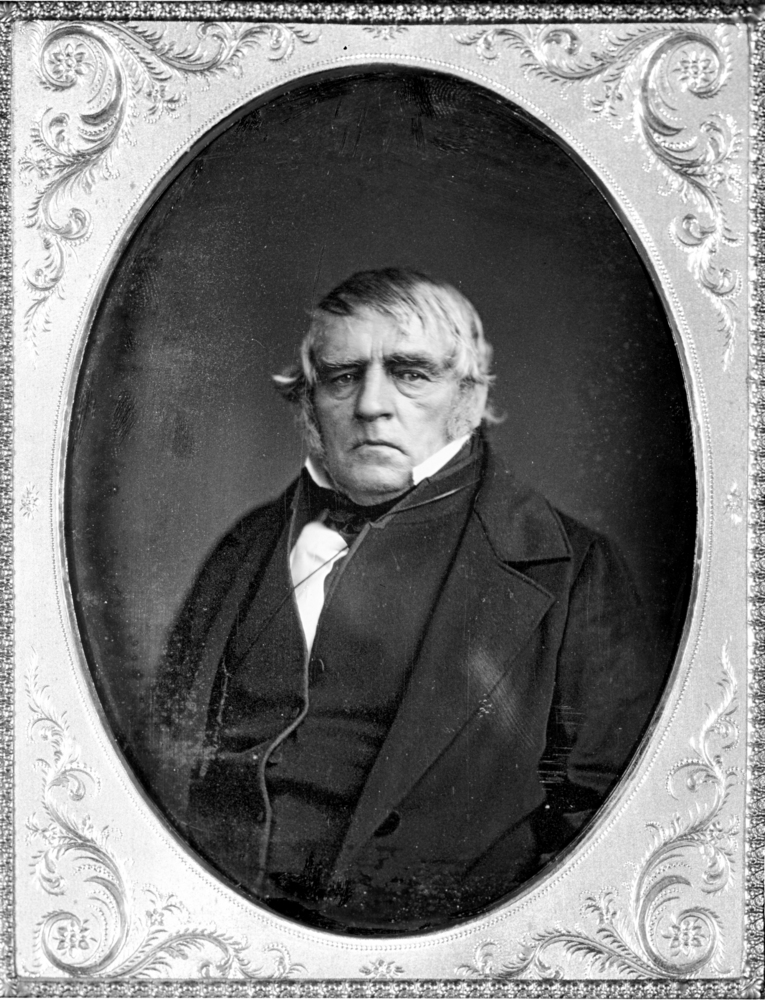

![George Simpson]()

George Simpson.

George Simpson Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi10125

-

![Dedication of Fort Vancouver renovation, 1974]()

Dedication of Fort Vancouver renovation, 1974.

Dedication of Fort Vancouver renovation, 1974 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

Related Entries

-

![Beaver]()

Beaver

The American Beaver (Castor canadensis) is often called “nature’s en…

-

![Fort George (Fort Astoria)]()

Fort George (Fort Astoria)

Fort George was the British name for Fort Astoria, the fur post establi…

-

![Fort Vancouver]()

Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver, a British fur trading post built in 1824 to optimize th…

-

![Fur Trade in Oregon Country]()

Fur Trade in Oregon Country

The fur trade was the earliest and longest-enduring economic enterprise…

-

![George Simpson (1786?-1860)]()

George Simpson (1786?-1860)

The highest-ranking officer of the Hudson's Bay Company in North Americ…

-

![James Douglas (1803-1877) in Oregon]()

James Douglas (1803-1877) in Oregon

James Douglas had a long connection to the Oregon Country. As an employ…

-

![John McLoughlin (1784-1857)]()

John McLoughlin (1784-1857)

One of the most powerful and polarizing people in Oregon history, John …

-

![North West Company]()

North West Company

First organized in 1779 by a small group of Canadian fur traders based …

-

![Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)]()

Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)

More than any other figure during the years of the Pacific Northwest's …

-

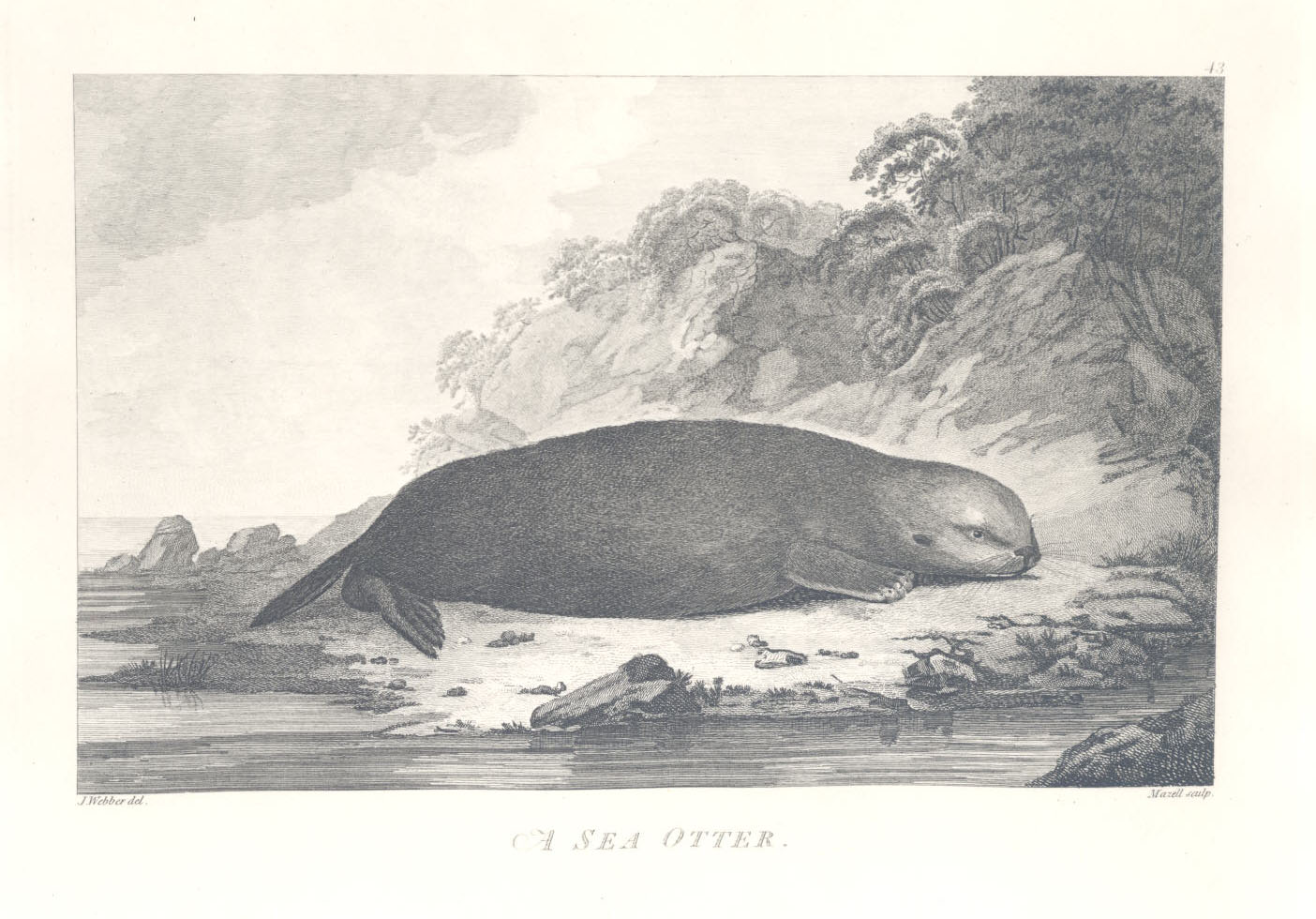

![Sea Otter]()

Sea Otter

America’s introduction to the lucrative Pacific Northwest Coast fur tra…

-

![Thomas McKay (1797-1849/1850?)]()

Thomas McKay (1797-1849/1850?)

Thomas McKay (pronounced “Mac-eye”) was a Hudson’s Bay Company fur trap…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Gibson, James R. Otter Skins, Boston Ships, and China Goods: The Maritime Fur Trade of the Northwest Coast, 1785-1841. Kingston, Ont.: McGill Queens University Press, 2001.

Hussey, John A. The History of Fort Vancouver and Its Physical Structure. Portland, Ore.: Washington State Historical Society, 1960.

Mackie, Richard Somerset. Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific, 1793-1843. Victoria, B.C.: University of British Columbia, 1997.

Merk, Frederick. The Oregon Question: Essays in Anglo-American Diplomacy and Politics. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967.

Reid, John Phillip. Contested Empire: Peter Skene Ogden and the Snake River Expeditions. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002.

Reid, John Phillip. Forging a Fur Empire: Expeditions in the Snake River Country, 1809-1824. New York: Arthur H. Clarke Co., 2011.

Wilson, Douglas C., and Theresa E. Langford, eds. Exploring Fort Vancouver. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2011.