At the beginning of the twenty-first century, only one Indian boarding school remained in Oregon—Chemawa Indian School, located along Interstate 5 at the 45th parallel north of Salem. Chemawa, an accredited high school that serves Native American and Alaska Native students, is the oldest continuously operated off-reservation boarding school in the United States.

From Colonial times, various forms of schooling for Native Americans were instituted by Christian missionaries. They brought Bible stories and elementary education to Indian communities and erected church schools nearby. Federal treaties included promises to build schools as partial compensation for ceded lands, but some tribes initially rejected the offer. It was not until reservations were established that an organized federal school system for Native Americans was formed. As the national economy drove congressional decisions, appropriations designated for the Indian Services ultimately defined the quality and quantity of Native education. Day schools and on- and off-reservation boarding schools were constructed, but they rarely met the needs of Indian communities.

The first mission and manual labor school for Indians in Oregon was constructed by Methodist missionary Jason Lee in 1835 at Mission Bottom on the east side of the Willamette River, near present-day Chemawa. Although it was not a boarding school per se, historical records suggest that during the mission school's brief existence students lived there and worked on the farm. With the influx of white settlers and the death of the local Indian population, primarily from disease, the school failed and in 1841 was relocated to Chemeketa on Mill Creek. Renamed the Indian Manual Training School, it became the Oregon Institute in 1844; the legislature granted the school a charter in 1853 as Willamette University.

In the mid-1850s, treaties submitted to Congress by Oregon and Washington Indian Commissioners Joel Palmer and Isaac Stevens promised to provide teachers and schools to tribes. The 1855 treaty with the Willamette Valley Indians obligated the federal government to establish manual labor schools among the Molala, Umpqua, and Kalapuya, which included the construction of buildings and the provision of subsistence for the students.

As early as 1859-1860, boarding schools were established on reservations in Washington and Oregon, the first at Fort Simcoe on the Yakama Reservation in Washington. In 1874, a boarding school was built at Warm Springs in Oregon, and others were later constructed at Siletz, Grand Ronde, Klamath, and Umatilla. In 1885, the annual report to the secretary of the Interior by Indian Commissioner John H. Oberly showed that the government had utterly failed in its obligation to educate Indian children. Few reservation schools had ever been built, and those that had were severely lacking.

In 1879, the secretary of the Interior authorized two federal off-reservation boarding schools. That fall, the Carlisle Indian School opened in Pennsylvania; and in February 1880, the Forest Grove Indian Industrial and Training School opened on land leased from Pacific University in Oregon. The first superintendent at the Forest Grove school was Lt. Melville C. Wilkinson, a veteran of the Civil War and formerly an aide-de-camp to Gen. Oliver Otis Howard. In 1884, the institution, staff, and student body were moved to a farm site along the railroad north of Salem, where more land was available. The post office there had been named Chemawa after the local band of Kalapuya Indians. The Salem Indian Industrial and Training School was briefly called the Harrison Institute, but eventually it became known simply as Chemawa.

Native youth from Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Alaska were the earliest to attend the school at Forest Grove and Salem. The students earned money that was used to purchase acreage for the institution, and they participated in the construction of both campuses. As the school expanded, younger and older students were recruited, and at times entire families were enrolled. Agents from reservations in all the western states and missionaries in Alaska sent children—often orphans—to Chemawa, and many children were separated from their families and forced to attend the school. Much of the curriculum of the early federal Indian boarding schools was focused on the destruction of Native languages and cultures and the enforcement of assimilation policies, and there is substantial documentation revealing the tragic consequences of this particular form of education on students, tribes, and communities.

During the late nineteenth century, boarding schools were promoted as a solution to what was called the "Indian problem." But whether the schools were under sectarian or federal control, little regard was given to traditional Indian values or teaching methods. The survival of Native societies depended on the acquisition of resources and the means of subsistence. They needed mobility, cooperation, seasonal adaptation, and spirituality based on a reverence for natural resources and social traditions. Conversely, the value systems and teaching tools of Euro-Americans focused on individualism, competition, established communities, private landownership, and the acquisition of natural resources for power and profit. Consequently, formal Indian education policies and curriculums often exacerbated existing cultural conflicts.

During the 1880s, congressional appropriations increased; and over the next three decades, the number of federally operated Indian schools in the United States rose from 160 to 383, including day and boarding schools and contract and mission schools. As transportation systems improved and public education became more accessible in the early twentieth century, many of the reservation schools were closed, and Indian students were sent to Chemawa or to public schools.

In the early twentieth century, Chemawa and some of the other federal boarding schools developed into nearly self-supporting communities and provided valuable training opportunities in the industrial arts and other fields. Recognizing the possible benefits for their children, some Native families chose to send their children to the boarding schools, beginning a tradition that has lasted for generations.

In the 1950s, many tribes in Oregon and Washington lost federal recognition, but some successfully fought for restoration and began to work toward the realization of tribal sovereignty. Tribal and intertribal Indian education associations were formed. Over the past few decades, many new tribal schools and colleges have been constructed throughout the country, which are managed in whole or in part by the tribes. At these schools and at Chemawa, contemporary paradigms for Indian education are still expanding and strive to incorporate both the academic and technological skills with cultural values and traditions. At the five remaining boarding schools still operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, students are now encouraged to explore and enhance their understanding of Indian history and their own individual tribal cultures and traditions.

-

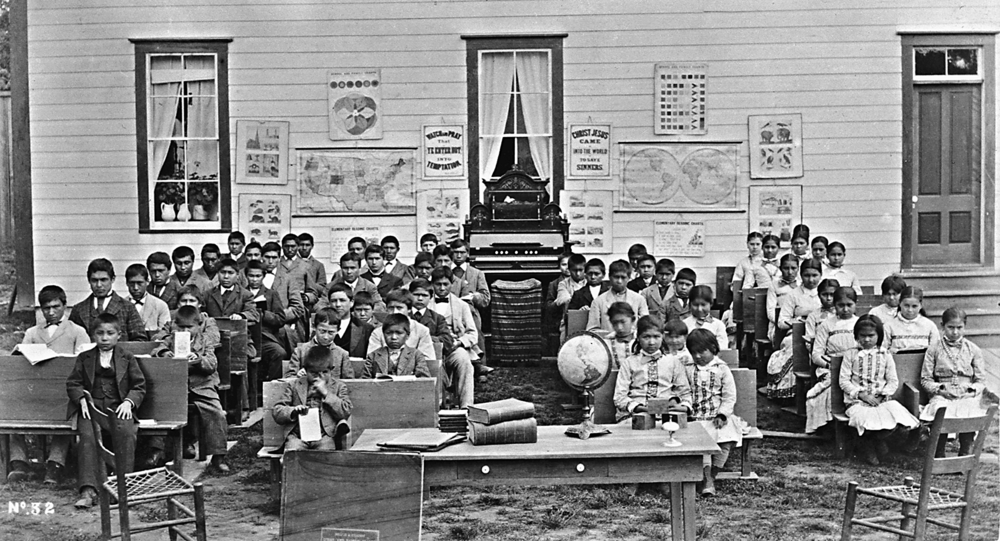

Indian Training School, Forest Grove, 1882.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 23784

-

![]()

Girls weaving on looms at the Chemawa Indian School, 1937.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, bb003867

-

![]()

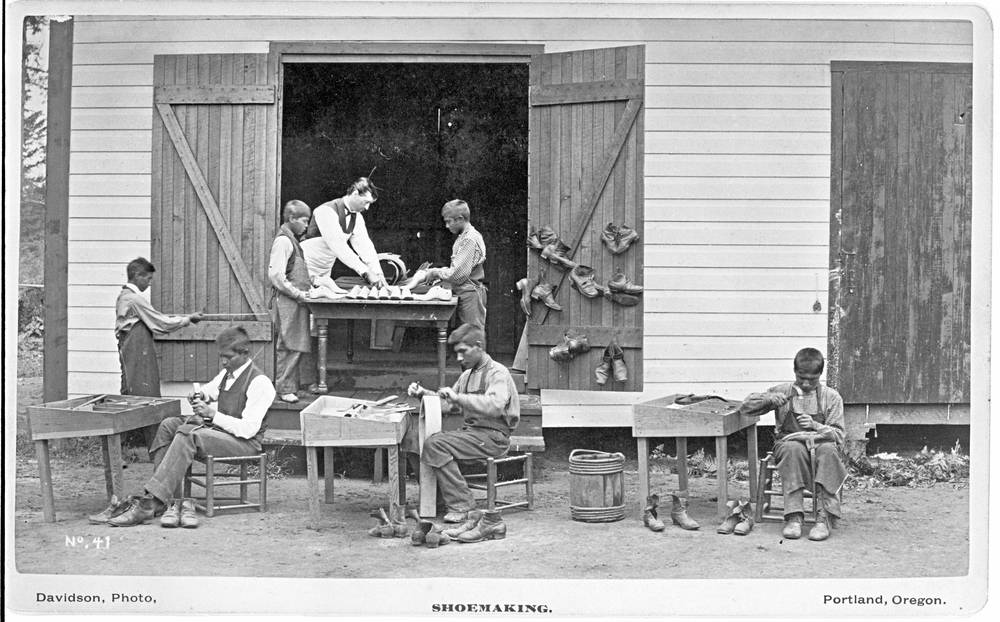

Shoemaking at the Indian Training School in Forest Grove, 1882.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb003866

-

![]()

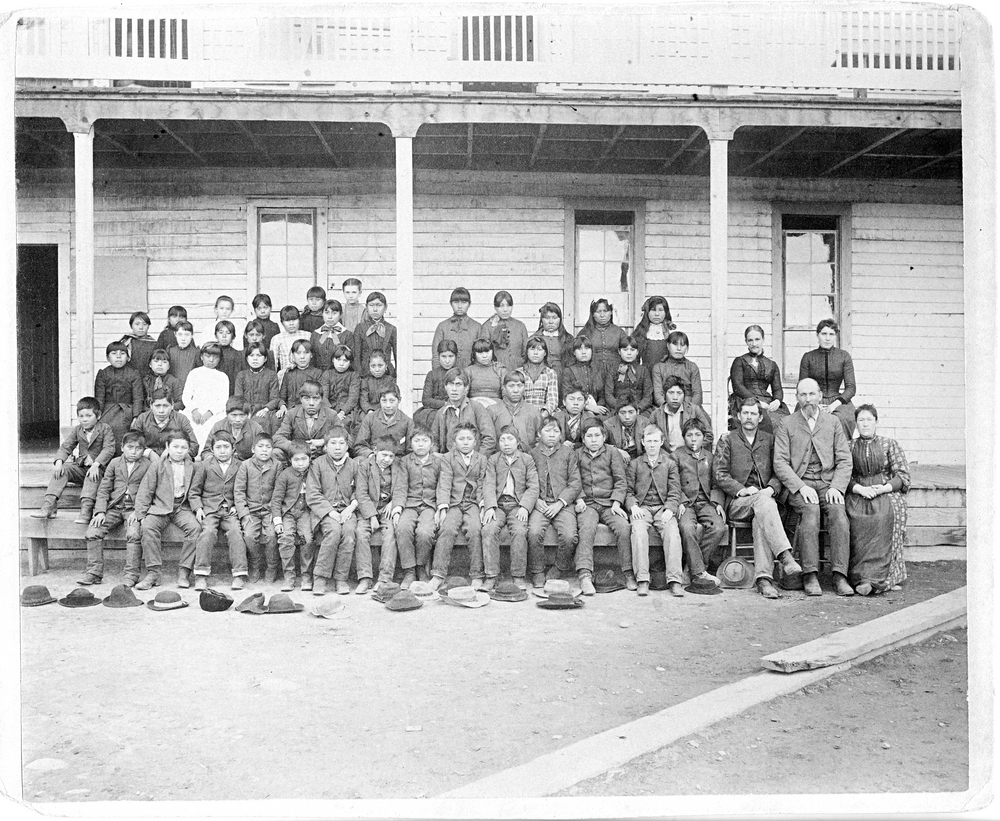

Students and staff stand in front of the Warm Springs Indian Training School, 1890.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb003865

-

![]()

Students standing at the entrance of the Chemawa Indian Training School in Salem.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, bb003857

-

![]()

Cheerleaders at the Chemawa Indian School.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, ba015936

-

![]()

Girls' dormitory at the Chemawa Indian School near Salem, Oregon..

Postcard, Oreg. State Univ. Library, Gerald W. Williams Coll.

-

![]()

Chemawa Indian Training School, 1905.

Oreg. State Univ. Archives, Walter R. Baker Photo Coll., P018:270

-

Indian Training School at Forest Grove, about 1882.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi 50121

Related Entries

-

![Chemawa Indian School]()

Chemawa Indian School

Chemawa Indian School, located in the mid-Willamette Valley north of Sa…

-

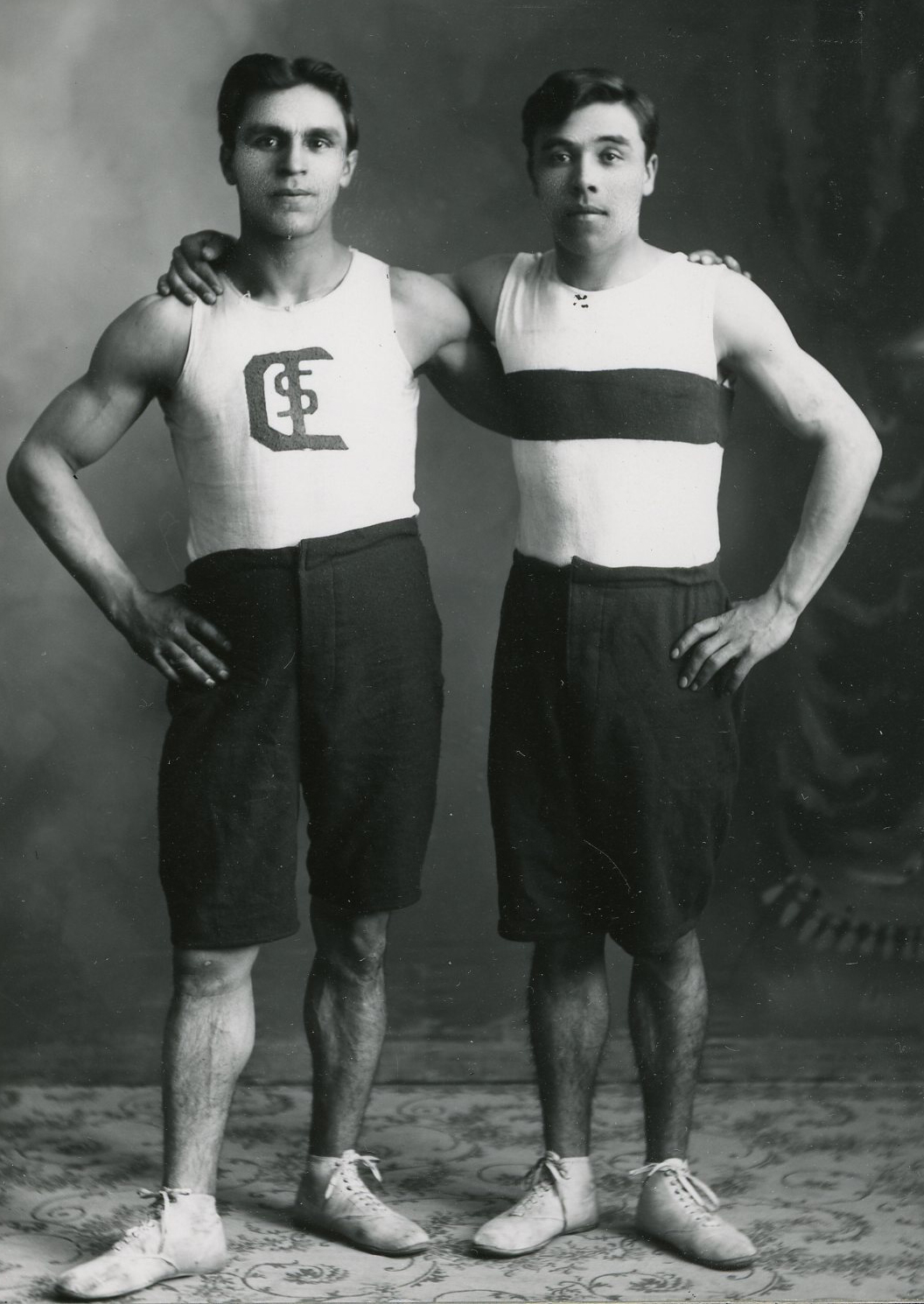

![Chemawa Indian School Athletics Program]()

Chemawa Indian School Athletics Program

Chemawa Indian School has been a leader in organized athletics in the W…

-

![Rutherford B. Hayes's visit to Oregon, 1880]()

Rutherford B. Hayes's visit to Oregon, 1880

In September and October 1880, Rutherford B. Hayes (1822-1893) became t…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Collins, Cary C. "The Broken Crucible of Assimilation: Forest Grove Indian School and the Origins of Off-Reservation Boarding-School Education in the West." Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. 101, no.4 (Fall 2000): 466-507.

Horton, Kami. "150 years ago, one of Oregon's first Indian boarding schools opened." Oregon Public Broadcasting. February 27, 2024.