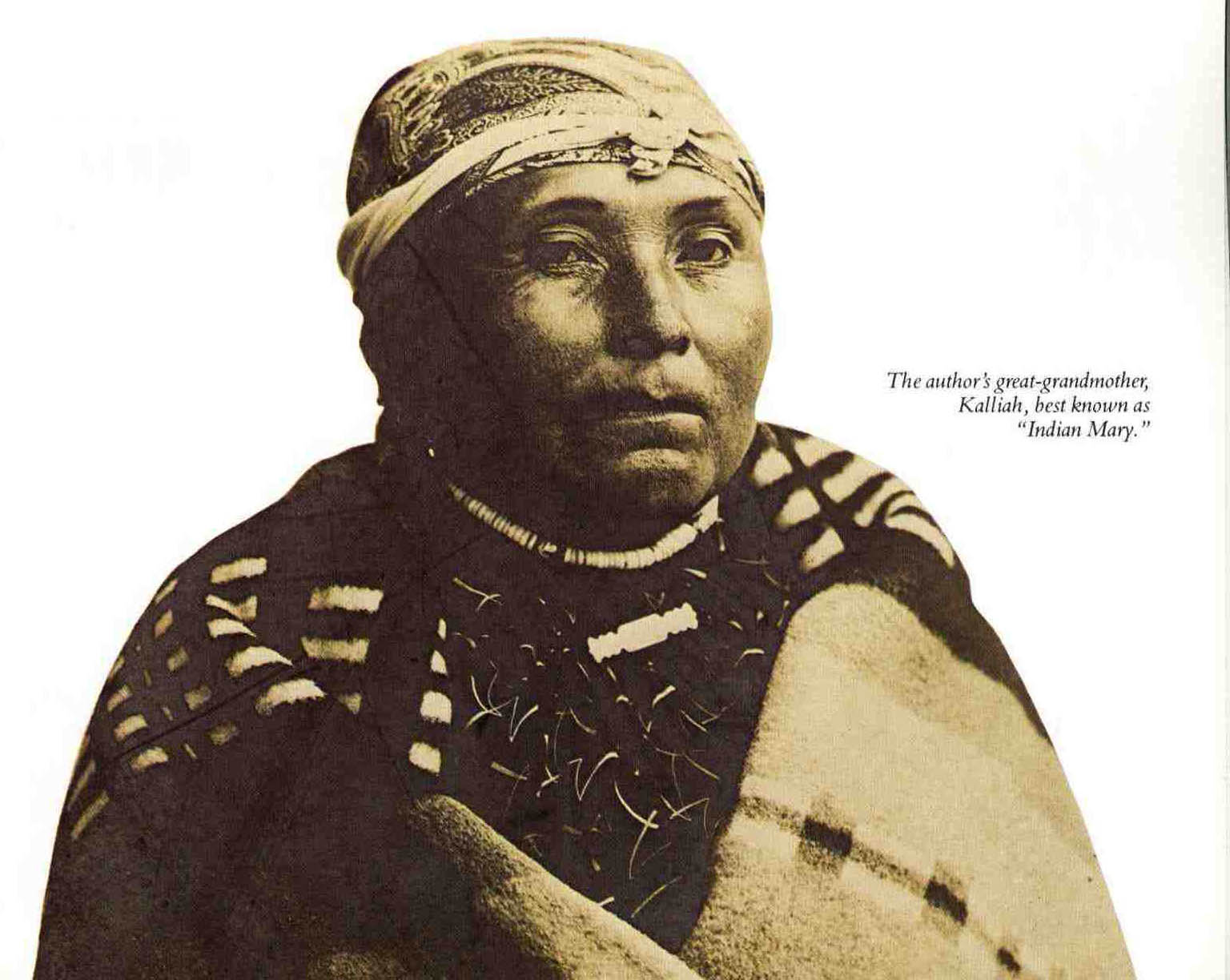

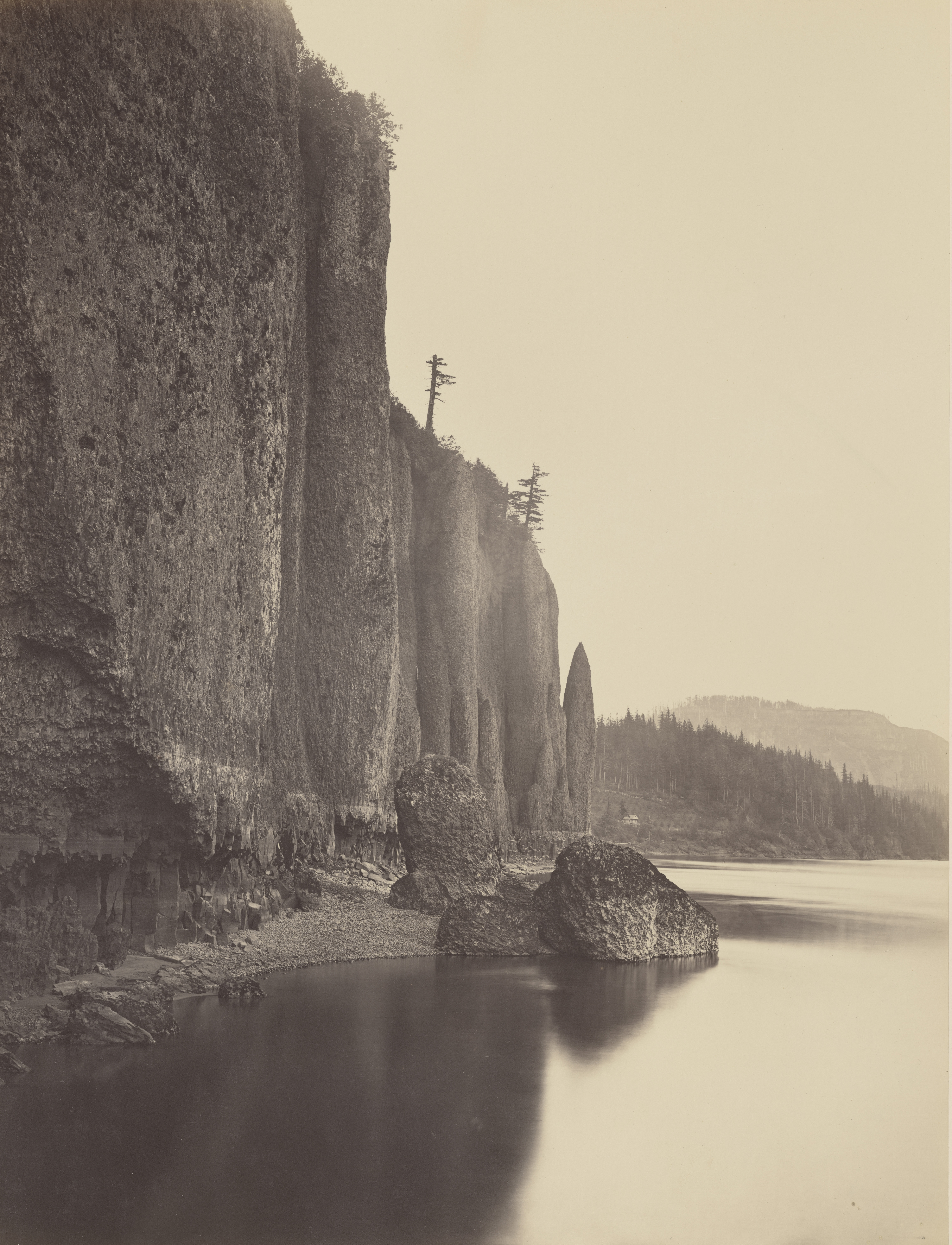

Kalliah Tumulth, also called Indian Mary, was a Cascade (Watlala) Chinook born in October 1854 to a signer of one of the main Oregon treaties. Kalliah was a strong, independent woman who, when a little girl, suffered the hanging of her father Chief Tumulth and eight other Cascade leaders by the U.S. Army. She endured considerable racism and hardships and resisted the movement of the tribes to reservations so that she could remain in her traditional homeland by the Cascade Rapids in the western Columbia River Gorge. These rapids near the present-day town of Cascade Locks were buried beneath the backwaters of Bonneville Dam in the 1930s, destroying her tribe's primary fishery. But her refusal to be removed to distant reservations anchored the family for generations in the Gorge with land, fishing rights, and traditional culture.

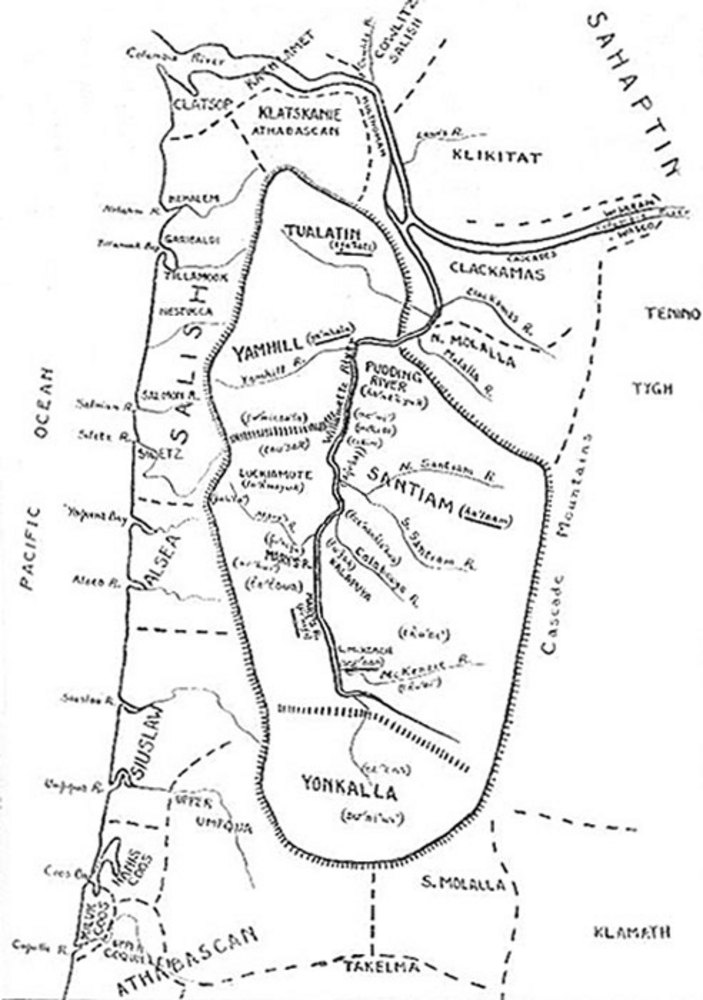

Kalliah's father was Ta-hon-nah Tumulth, who in 1855 signed the Willamette Valley Treaty (also known as the Treaty with the Kalapuya Etc.) as the First Chief of the Wal-lal-lah Band of Tumwaters, the Upper Chinookan people now known as Cascade Indians. Even though the reservation for the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde established by this ratified treaty ended up near the Oregon coast, the eastern boundary of the treaty's ceded area is the Cascade Rapids and crest of the Cascade Range.

In April 1856, Tumulth and eight other Cascade leaders were hanged by the U.S. Army, under the direction of Lt. Phil Sheridan, following what some called the Cascade Massacre—an attack on pioneer settlements by nonlocal Yakama and Klickitat people. Kalliah's mother Susan Tumulth (Tomolcha) ended up living with Chinookan relatives near Oregon City and was a member of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde.

Where Susan and her children, including Kalliah, were resettled following the hanging is in some doubt. Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer wrote that the surviving local Cascade Indians were sent to the Grand Ronde Reservation, but some family oral history suggests that they first went upriver, which is consistent with the establishment of the temporary White Salmon Reservation for Gorge Natives that existed for a few years between the White Salmon and Klickitat Rivers. After White Salmon was closed in 1859, some family members were enrolled at the Yakama Reservation by agents of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, but in the mid-1900s their descendants were denied enrollment for not having any Yakama lineage and so could not inherit allotments. Kalliah had earlier given up her Yakama allotment for one just downriver from the Cascade Rapids.

When Kalliah grew up, she returned to the Cascades and married a Wish-ham man Henry Will-wy-ity, the last name used on her tombstone and some legal documents. After her husband's death in the 1870s, Kalliah married Johnny Stooquin, a Cascade man, and traded horses for a 160-acre parcel of land just downriver from Che-che-op-tin (Beacon Rock). Kalliah's brother Joseph Tumulth built her a cabin where her daughters Amanda Stooquin Williams and Abbie Weiser Estabrook were born and raised.

Kalliah got a contract with the U.S. government to deliver on horseback the local mail brought up from Portland. Some settlers tried to file claims on Kalliah's land since Indians could not legally own land then. Because of her mail contract, the Vancouver Indian agent sided with Kalliah and in 1893 got President Grover Cleveland to sign a proclamation putting her land into trust status. Her allotment remained in family ownership until the 1980s, when Congress established it as the beginning of Franz Lake National Wildlife Refuge, where tundra swans and wapato have returned. The lake's year-round water supply is named Indian Mary Creek. Indian Mary Road, the road into the refuge, passes her cabin site, where her family harvested fruit from the orchard until the refuge was established. (Please note that Kalliah is not the same "Indian Mary" for whom a campground on the Rogue River is named.)

In 1891, Kalliah fought to preserve Native fishing rights. She and sixty-eight other Cascade Indians hired a Washington, D.C., attorney to try to get their traditional lands on the north shore, from Wind Mountain downriver to Beacon Rock, set aside for their fishing sites. This legal proposal asked for financial compensation "in case they are permanently deprived of said fishing rights and lands of which they are now dispossessed by the encroachment of settlers and others." Even though the 1855 Willamette Valley Treaty contained provisions for the U.S. government to purchase lands on the north shore for the Cascade Indians, this never happened.

Despite local racism, which was common against Indians in the early to mid-twentieth century, Kalliah and her daughters and grandchildren established themselves in the local community without compromising their heritage. As Indians were often pressured to do, they also took so-called Christian names, but the family was unabashedly proud of their heritage, including speaking Kiksht, the Chinookan language used by the Cascade and Clackamas peoples.

A few months before her death in December 1906, Kalliah was forced to move because the Southern Pacific & Southwestern railroad was building tracks by her cabin. She is buried with her mother, her two sons (who died in childhood), and most of her family in the Cascade Cemetery near North Bonneville. This cemetery, which includes a mass grave of Cascade people relocated from the main cemetery on Bradford Island during the construction of Bonneville Dam, was called the Cascade Pioneer Cemetery. In 1992, following the death of Kalliah's grandson Clyde Williams, the cemetery was renamed the Cascade Indian & Pioneer Cemetery.

-

![]()

Kalliah Tumulth (Indian Mary).

Courtesy Chuck Williams

-

![]()

Kalliah Tumulth (Indian Mary), second from left.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi58422

Related Entries

-

![Cascade Locks]()

Cascade Locks

A massive ground movement known as the Bonneville Landslide, which occu…

-

![Columbia River]()

Columbia River

The River For more than ten millennia, the Columbia River has been the…

-

![Columbia River Gorge]()

Columbia River Gorge

The Columbia River Gorge is a striking natural landscape of mountains, …

-

![Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde]()

Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon is a confede…

-

![Kalapuya Treaty of 1855]()

Kalapuya Treaty of 1855

The treaty with the Confederated Bands of Kalapuya (1855) is the only r…

-

![Philip Henry Sheridan (1831-1888)]()

Philip Henry Sheridan (1831-1888)

Before he gained fame as commander of the cavalry forces of the Army of…

-

![Willamette Valley Treaties]()

Willamette Valley Treaties

From 1848 to 1855, the United States made several treaties with the tri…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Boyd, Robert, Ken Ames, and Tony Johnson. Chinookan Peoples of the Lower Columbia. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2013.

French, David, and Katherine French. "Wasco, Wishram, and Cascades." In Handbook of North American Indians: Plateau. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 1998.

Williams, Chuck. Bridge of the Gods, Mountains of Fire: A Return to the Columbia Gorge. San Francisco: Friends of the Earth, 1980.

Zucker, Jeff, Kay Hummel, and Bob Hogfoss. Oregon Indians: Culture, History, and Current Affairs. Portland: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1983.