The 281-mile-long John Day River in north-central Oregon is the longest river flowing entirely within the state, the longest undammed river in Oregon, and the third-longest undammed river in the continental United States. The river system, extending 9,500 miles from the Blue Mountains to the Ochocos, drains over 8,000 square miles and is fed by approximately 1,200 named and 3,150 unnamed streams. Because of its remarkable properties, segments of the river are protected by the Oregon Scenic Waterways Act and the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. The river is the larger of two Oregon rivers named after John Day, a hunter with the Pacific Fur Company; the other is a six-mile-long tributary of the Columbia near Astoria.

Over ten thousand years of continuous human use of the main stem watershed—especially its fishery—is supported by the archaeological record and has been affirmed by members of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, and the Burns Paiute Tribe, who continue to use the river corridor for hunting, fishing, and other activities. Western Columbia River Sahaptins—known as the Tenino or Warm Springs, the Wyampam, and the John Day—originally held most of the John Day watershed. By the nineteenth century, they shared portions of the upper basin with Bannock and Northern Paiutes in a “sometimes tense and unfriendly association,” according to historians Stephen Dow Beckham and Florence Lentz.

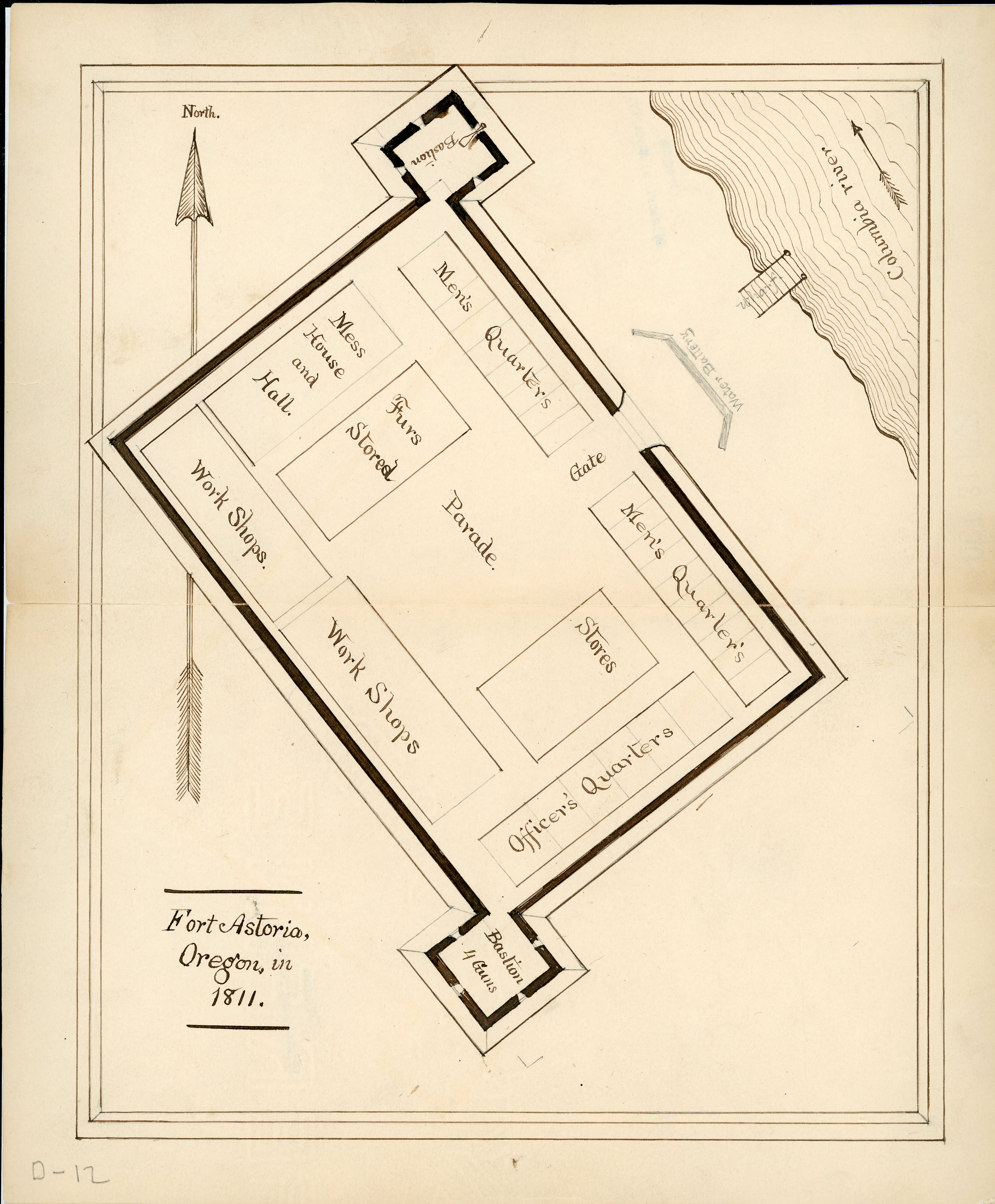

The Lewis and Clark Expedition identified the mouth of the river on October 21, 1805, and named it after expedition member Jean Baptiste LePage. When the North West Company’s David Thompson passed the river a few years later, on August 2, 1811, he recorded its name as the Torks Paez River. In April 1812, near the mouth, Ramsay Crooks and John Day—part of the Pacific Fur Company’s overland expedition to Astoria—encountered a group of Natives riven by a recent murder perpetrated by a company employee from the Astoria post. In retaliation, they took the rifles and equipment from Crooks and Day and sent them away naked. The two men were found upriver days later by a Pacific Fur Company party. The river near the site of the encounter subsequently became known as the John Day River, “so called from its having been the place at which that hunter was attacked.”

Hudson’s Bay Company fur trapping expeditions into the Snake Country explored sections of the river in search of beaver and other fur-bearing animals during the 1820s. Later EuroAmericans found the river an impediment to travel and developed roads such as the Oregon Trail and The Dalles Military Road, which either crossed the river or avoided it altogether. The discovery of gold in the Canyon Creek area in 1861 attracted thousands of people to the John Day’s upper basin and initiated the area’s placer mining, ranching, lumber, and wheat-farming traditions.

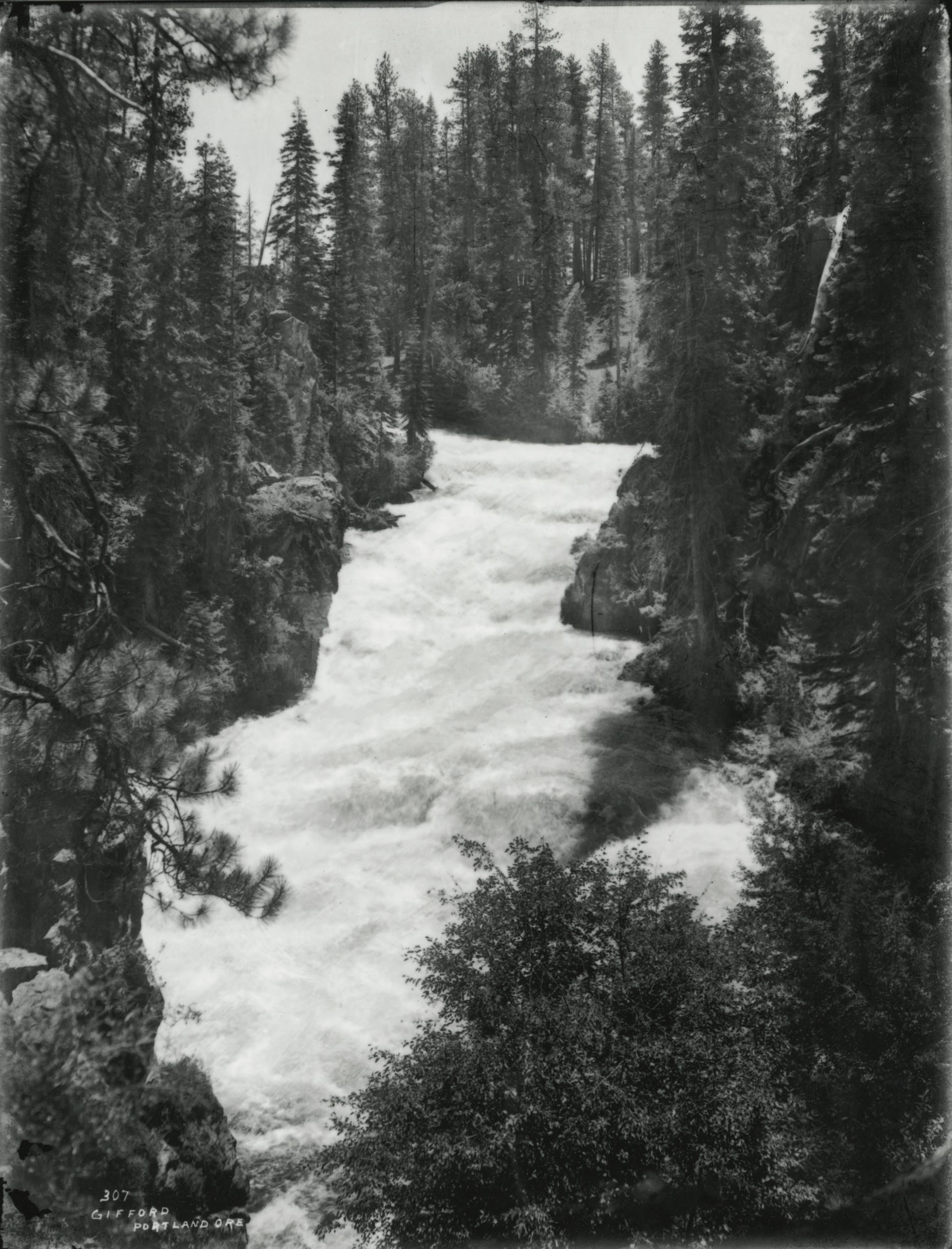

Fed by tributary creeks originating from elevations of up to 8,000 feet in the Malheur National Forest, the main stem of the John Day begins its journey by winding north before bending westward near Prairie City, where streams add water from mountains to the north and south, including the north side of the Strawberry Range and 9,055-foot-high Strawberry Mountain. Joined by the South Fork at Dayville, the river resumes its northerly flow past the deep canyon of Picture Gorge and two units of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument until, fed by the North Fork near Kimberly, it takes a westward course. At Parrish Creek, the river becomes an Oregon Scenic Waterway. After adding Service Creek, it sheds the adjacent state highway and becomes a national wild and scenic river near river mile 190, entering the Deschutes-Umatilla plateau.

For the next 180 river miles to Tumwater Falls, the river twists through some of the most remote and rugged canyonland in central Oregon. Passing the Spring Basin Wilderness nearly ten miles after its final northward bend through steep, eroded lava beds, the river meets State Highway 218 at Clarno before flowing through the scenic canyons of the North Pole Ridge, Thirtymile, and Lower John Day Wilderness Study Areas, defining the boundary between Sherman and Gilliam Counties.

Near the crossing of State Highway 206, the John Day enters Cottonwood Canyon State Park and flows past historic livestock ranches and the domain of the largest herd of California bighorn sheep in the state. Downriver of Rock Creek, at McDonald Ferry, the river’s shallows provide a natural ford that thousands of Oregon Trail resettlers used to cross their wagons and livestock. From this river crossing—part of the Oregon National Historic Trail—the river’s final twenty miles are bisected at Tumwater Falls, where the river’s wild and scenic designation ends. The John Day’s final 10 miles run almost parallel to the Columbia River, isolating a peninsula of land known as The Nook. The waters of the Columbia River’s Lake Umatilla, constrained by the John Day Dam, restrict the river’s free flow for its remaining miles before it joins the Columbia at LePage Park at an elevation of 274 feet. At the river mouth, discharge ranges annually from a low of 50-60 cubic feet per second in the summer to as much as 10,000 cubic feet per second in the spring. Although undammed, the river has irrigation diversions, which may account for it going dry in the lower reach during the late summer months of 1966, 1973, and 1975.

In 1988, Senator Mark O. Hatfield proposed the addition of the main stem of the John Day and thirty-nine other Oregon rivers to the National Wild and Scenic River System. The Omnibus Oregon Wild and Scenic Rivers Act designated as wild and scenic 147.5 miles of the John Day’s main stem, plus 47 miles of its South Fork and 54.1 miles of its North Fork.

Despite problems with pollution from runoff and solar heating, the river hosts one of the most significant runs of wild summer steelhead and chinook salmon in the Columbia River system. Federal, state, and local agencies manage the river and the adjacent resources that visitors use for rafting, fishing, hiking, and camping.

-

![]()

John Day River near Cottonwood Canyon, 2018.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management, photo by Greg Shine

-

![]()

Burnt Ranch, John Day River.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi4626, photo file 905j

-

![]()

Fishing on the John Day River, 1954.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., photo file 905j

-

![]()

John Day River, 1954.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 13280, photo file 905j

-

![]()

The mouth of the John Day River, flowing into the Columbia, 1964; John Day Dam in the background.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Oregonian, 57783, photo file 905j

-

![]()

John Day River near Cottonwood Canyon, 2018.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management, photo by Greg Shine

-

![]()

John Day River, 2016.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management, photo by Bob Wick

-

![]()

John Day River, 2016.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management, photo by Bob Wick

-

![]()

Cliff swallow nests along the basalt canyon walls along the John Day River, 2018.

Courtesy Bureau of Land Management, photo by Greg Shine

Related Entries

-

![Astor Expedition (1810-1813)]()

Astor Expedition (1810-1813)

The Astor Expedition was a grand, two-pronged mission, involving scores…

-

![Blue Mountains]()

Blue Mountains

The Blue Mountains, perhaps the most geologically diverse part of Orego…

-

![David Thompson (1770-1857)]()

David Thompson (1770-1857)

British fur agent, surveyor, explorer, and cartographer David Thompson …

-

![John Day Fossil Beds National Monument]()

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, established in October 1975, sh…

-

![National Wild and Scenic Rivers in Oregon]()

National Wild and Scenic Rivers in Oregon

The world's first and most extensive system of protected rivers began w…

-

![North Fork John Day River]()

North Fork John Day River

Flowing 113 miles westward from the Blue Mountains, the North Fork John…

-

![South Fork John Day River]()

South Fork John Day River

From its headwaters in the fir and ponderosa pine forests of Grant and …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Beckham, Stephen Dow with Florence K. Lentz. Rocks & Hard Places: Historic Resources Study, John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Seattle, Wash.: National Park Service, 2006.

Palmer, Tim. Field Guide to Oregon Rivers. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2014.

Ross, Alexander. Adventures of the First Settlers on the Oregon or Columbia River. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 1849.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, John Day River, accessed January 5, 2018.

U.S. National Park Service. John Day River: Wild and Scenic River Study. U.S. National Park Service, September 1979.