In 1973, Oregon took a pioneering step in land use planning. Signed into law on May 29, 1973, Oregon Senate Bill 100 created an institutional structure for statewide planning. It required that every Oregon city and county prepare a comprehensive plan in accordance with a set of general state goals. While preserving the principle of local responsibility for land use decisions, it simultaneously established and defined a broader public interest at the state level. Supervised by a Land Conservation and Development Commission, the Oregon system has been an effort to combine the best of these two approaches to land use planning. The very existence of Oregon's planning system has helped to inspire and justify similar programs elsewhere. Its details have been studied, copied, modified, and sometimes rejected as Florida, New Jersey, Georgia, Washington, Maryland, and other states have considered "second generation" systems of state planning.

Early Land Use Laws

When the legislature adopted Senate Bill 100, formal land use planning in Oregon was just over fifty years old. The state's initial planning legislation in 1919 and 1923 granted cities the authority to develop plans and land use regulations. In a 1920 referendum, Portland voters narrowly rejected citywide zoning under the first enabling act. Four years later, they overwhelmingly approved a simpler zoning ordinance. Planning remained solely a city function until 1947, when the legislature extended similar authority to counties in response to chaotic growth of urban fringe areas during the boom years of World War II. Counties were authorized to form planning commissions, which could recommend "development patterns" (renamed "comprehensive plans" after 1963). Unlike cities, counties were required to develop zoning and other regulations to carry out their plans.

The concern with disorderly growth that led to county planning in the 1940s grew into serious worries about suburban sprawl as Oregon began to grow rapidly in the 1960s. By the end of that decade, Willamette Valley residents from Eugene to Portland viewed sprawl much more broadly as an environmental problem that wasted irreplaceable scenery, farmland, timber, and energy. Metropolitan growth was explicitly associated with the painful example of southern California. Governor Tom McCall summarized the fears of many of his constituents in January 1973, when he spoke to the Oregon legislature about the "shameless threat to our environment and to the whole quality of life—unfettered despoiling of the land" and pointed his finger at suburbanization and second home development.

The initial impulse for state land-use legislation came from the farms rather than the cities. The center of concern was the hundred-mile-long Willamette Valley, where the blue barricade of the Coast Range on one side and the high cones of the Cascades on the other reminded residents that land is finite. The first steps toward the idea of "exclusive farm use" between 1961 and 1967 involved legislative action to set the tax rate on farm land by land rental values—in effect, by its productive capacity as farm land—rather than by comparative sales data which might reflect the demand for suburban development. A conference on "The Willamette Valley—What Is Our Future in Land Use?" held early in 1967 spread awareness of urban pressures on Oregon's agricultural base. With key members drawn from the ranks of Oregon farmers, the Legislative Interim Committee on Agriculture responded by developing the proposal that became Senate Bill 10, Oregon's first mandatory planning legislation.

Senate Bills 10 and 100

Adopted in 1969, SB 10 required cities and counties to prepare comprehensive land-use plans and zoning ordinances that met ten broad goals. The deadline was December 31, 1971. However, the legislation failed to establish mechanisms or criteria for evaluating or coordinating local plans, allowing some counties to opt for pro forma compliance. McCall's successful reelection campaign in 1970 called for strengthening SB 10. At the same time, 55 percent of the state's voters supported the law in a referendum.

The Oregon legislature acted in 1973 to correct flaws in the 1969 law. A state-sponsored report by San Francisco landscape architect Lawrence Halprin titled "Willamette Valley: Choices for the Future" helped to set the stage in the fall of 1972. McCall raised the curtain in January 1973 with an address to the legislature. "There is a shameless threat to our environment," he said, "and to the whole quality of life . . . the unfettered despoiling of the land. Sagebrish subdivisions, coastal condomania, and the ravenous rampage of suburbia in the Willamette Valley all threaten to mock Oregon's status as the environmental model for the nation. We are in dire need of a state land use policy, new subdivision laws, and new stanards for planning and zoning by cities and counties. The interest of Oregon for today and in the future must be protected from the grasping wastrels of the land." Much credit for passage of SB 100 goes to Senator Hector Macpherson, a Linn County dairy farmer convinced of the need to fend off the suburbanization of the entire valley. Drawing on his experience on the Linn County Planning Commission, he articulated the importance of a statewide planning program in protecting and enhancing agricultural investment. When the leadership of the 1971 legislature blocked formation of a formal interim study committee, Macpherson had worked with McCall to set up an informal "Land Use Policy Committee" to suggest ways to improve SB10. Members represented the Governor's office, environmental groups, and business organizations.

In drafting the new legislation, committee members relied heavily on Fred Bosselman and David Callies's book The Quiet Revolution in Land Use Control, published for the federal Council on Environmental Quality in 1972. The volume described state-level land planning programs in Hawaii and Vermont and a number of state efforts to protect such environmentally sensitive lands as Massachusetts wetlands and Wisconsin shorelands. Perhaps the central message for those crafting the Oregon legislation was the need for state programs to build in continuing local participation.

The final version passed both houses of the legislature by comfortable margins in May 1973. In total, forty-nine out of sixty legislators from Willamette Valley districts voted in favor of SB 100. Only nine of their thirty colleagues from coastal and eastern counties agreed. The legislation created the Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC) to oversee compliance of local planning with statewide goals. The Commission is composed of seven members appointed for four-year terms by the Governor and confirmed by the State Senate. One member is appointed from each of Oregon's five Congressional districts and two from the state at large. At least one but no more than two members must be from Multnomah County, the state's largest and most urban county. At least one member must be an elected city or county official at the time of appointment. Staff support for LCDC and the planning program comes from the Department of Land Conservation and Development.

As its first task, the new LCDC rewrote the state planning goals in 1974 after dozens of workshops throughout the state. The ten goals of the 1969 legislation were made more clear and precise and four new goals were added. All fourteen goals were adopted in December 1974. An additional goal on the Willamette River Greenway was added in December 1975 and four goals focusing on coastal zone issues were added in December 1976 (see Senate Bill 100).

Oregon's land use program matured between 1974 and 1982. Implementation required procedural innovations. LCDC defined a formal process of "acknowledgment" to certify that local plans actually met state goals. It similarly defined a requirement for "periodic review" to make sure that plans were adapted to changing circumstances. The legislature established the Land Use Board of Appeals (LUBA) as a specialized tribunal to deal with the increasingly complex details of land use law and cases. The first local plans were acknowledged in 1976, the last nearly a decade later.

Economic Debates

The program also survived three referendum challenges, winning voter approval by a margin of 57 percent to 43 percent in 1976 and a margin of 61 percent to 39 percent in 1978. Support was strongest in Portland, Salem, and Eugene. In 1978, the LCDC program also gathered support along the northern coast and in south-central counties where rapid recreational development had brought problems of urban services to the localities.

During the depression of 1981-82, however, LCDC became the target of frequent complaints that planning requirements inhibited economic development. Opponents of the state planning system placed an anti-LCDC measure on the November 1982 ballot, calling for the abolition of LCDC, return of all land-use planning authority to localities, and retention of state goals purely as guidelines. Editorial discussion debated the economic impacts of statewide planning, with most newspapers accepting the view that statewide planning actually encouraged economic development by requiring the designation of industrial land, stimulating tourism, and allowing large corporations to make plans for the long term. A task force headed by Umatilla agriculturalist Stafford Hansell heard testimony from more than four hundred Oregonians and reported essentially the same conclusions to Governor Vic Atiyeh. The election returns showed the same regional divisions as before, with most of the opposition from ranching counties in the southeastern corner of the state and from lumbering counties in the southwestern corner.

The 1982 referendum was the last comprehensive effort to alter the Oregon planning system for nearly two decades. A statewide economic slump from 1980 to 1986 meant little demand for new housing and few pressures for land conversion, leaving the assumptions of most local plans unchallenged. The legislature also tried to blunt potential opposition to the Oregon system by developing alternative procedures for deciding the location of controversial public facilities such as prisons.

Housing and Property Rights

The main arena in which the Oregon system has addressed social issues has been housing. Reflecting the strong interest during the 1970s in "fair share" housing policies that tried to distribute low-income housing throughout entire metropolitan areas, Goal 10 requires that jurisdictions provide "appropriate types and amounts of land . . . necessary and suitable for housing that meets the housing needs of households of all income levels." In an early assertion of its authority, LCDC forbade the small town of Durham in Washington County to shift its entire multifamily zone to single-family. The city of Milwaukie ran into trouble by trying to set more stringent review standards for apartments than for detached houses. In 1982, the small suburban Portland municipality of Happy Valley became a test case when LCDC ordered it to plan for a substantially greater residential density than its residents desired.

Oregon land use planning was a model for other states in the 1980s and 1990s. Oregonians have been key players in national communication networks on state planning, with staff of the land use advocacy group 1000 Friends of Oregon playing especially prominent roles. Several aspects of the state system have been especially "exportable." These include its emphases on certainty and timeliness in procedures; its requirement of consistency between local plans and state standards; its use of urban growth boundaries; and its emphases on the protection of resource land and affordable housing.

In November 2000, however, 53 percent of Oregon voters approved Measure 7. This amendment to the state constitution required government compensation for any and all loss of potential property value because of state or local regulations affecting the use of land (making it the nation's most stringent property rights measure). Non-metropolitan areas voted heavily for the measure, so it also picked up substantial support in Portland's suburban counties. It can be read both as a reflective of a national trend toward free market values and as an indication of frustration with a planning system with increasingly elaborate sets of regulations. Measure 7 never went into effect because the Oregon Supreme Court overturned the vote on the technical grounds that it simultaneously amended more than one clause of the state constitution.

Because of the court action, and because the legislature was not able to devise an acceptable replacement measure, property rights advocates placed Measure 37 on the ballot, this time structuring it as simple legislation rather than a constitutional amendment. The measure passed overwhelmingly in November 2004. It requires local governments, on request of a property owner, to waive regulations imposed since the most recent transfer of ownership or pay compensation for lost value. In response, the legislature placed Measure 49 on the November 2007 ballot to clarify technical points and to partially limit the applicability of Measure 37.

-

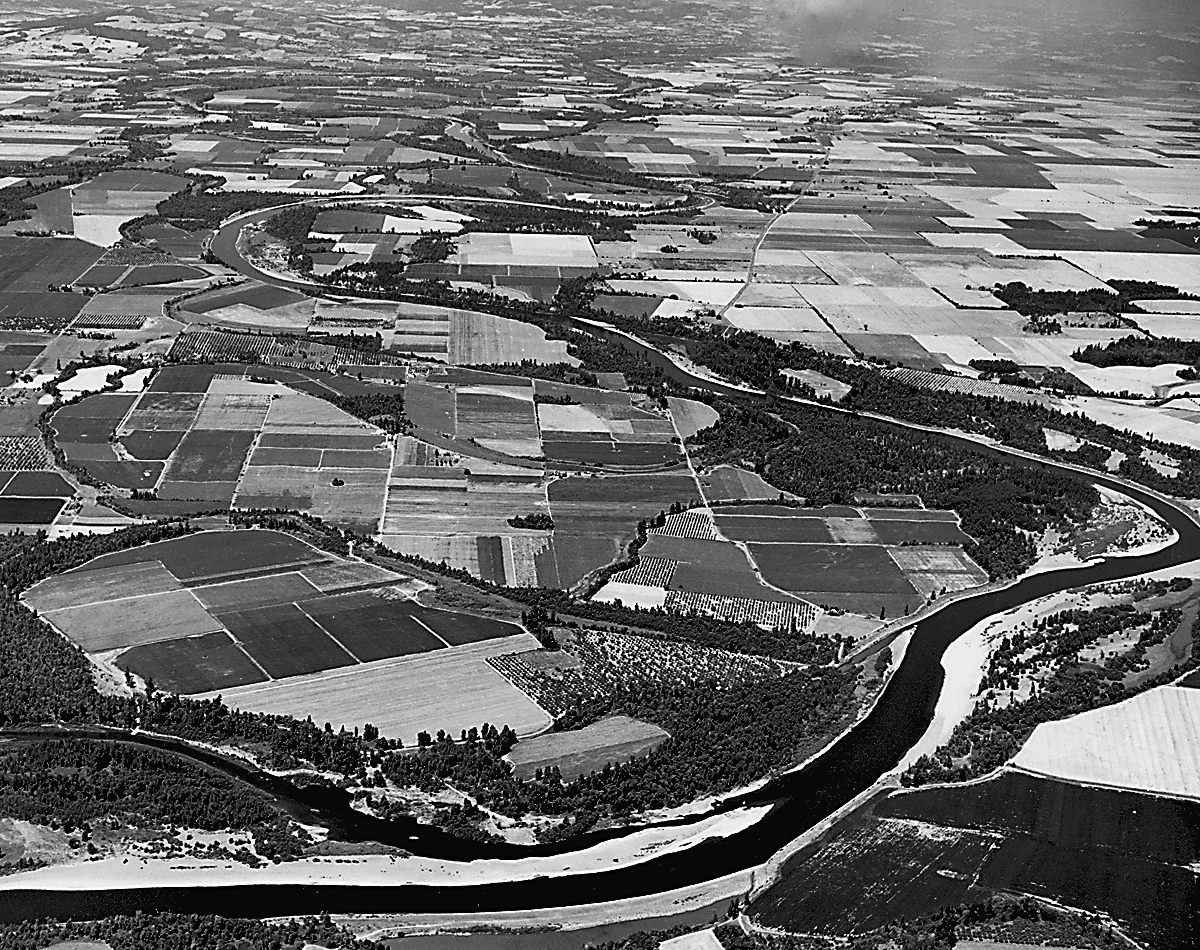

Willamette Valley, north of Albany, about 1970.

Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb003272

-

![]()

First page of Senate Bill 10.

Courtesy Oregon State Archives

-

![]()

First page of Senate Bill 100.

Courtesy Oregon State Archives

Related Entries

-

![Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC)]()

Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC)

In 1973, Oregon Senate Bill 100 established the Land Conservation and D…

-

![Metro Regional Government]()

Metro Regional Government

Metro is a regional agency that serves the urbanized portions of Multno…

-

![Senate Bill 10]()

Senate Bill 10

The enactment of Senate Bill 10 in 1969 was a crucial step on the path …

-

![Senate Bill 100]()

Senate Bill 100

Signed into law on May 29, 1973, Oregon Senate Bill 100 created an inst…

-

![Thomas William Lawson McCall (1913-1983)]()

Thomas William Lawson McCall (1913-1983)

Tom McCall, more than any leader of his era, shaped the identity of mod…

-

Urban Growth Boundary

Each urban area in Oregon is required to define an Urban Growth Boundar…

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Abbott, Carl, Deborah Howe, and Sy Adler, eds., Planning the Oregon Way: A Twenty Year Evaluation. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 1994.

Abbott, Carl, Deborah Howe, and Sy Adler. A Quiet Counterrevolution in Land Use Regulation: The Origins and Impact of Oregon's Measure 7. Housing Policy Debate (2004)

DeGrove, John. Planning, Policy and Politics: Smart Growth in the States. Cambridge, Mass.: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 2005.

Judd, Richard, and Christopher Beach. Natural States: The Environmental Imagination in Maine, Oregon, and the Nation. Washington D.C.: Resources for the Future, 2003.

Knaap, Gerrit, and Arthur C. Nelson, The Regulated Landscape: Lessons on State Land use Planning from Oregon. Cambridge, Mass.: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 1992.