Tom McCall, more than any leader of his era, shaped the identity of modern Oregon. As governor from 1967 to 1975, McCall, a Republican, pioneered a doctrine of balancing economic growth with environmental protections and took the lead in establishing safeguards for the state’s beaches, rivers, and farmlands by curbing pollution and suburban sprawl. His leadership, defined by bold actions and lyrical speeches, helped transform Oregon from a political backwater to a state renown for progressive ideals.

Thomas William Lawson McCall was born on March 22, 1913, in Egypt, Massachusetts, on an estate owned by his maternal grandfather, Thomas W. Lawson, a wealthy Boston stock promoter. Lawson had given McCall’s parents, Henry McCall and Dorothy Lawson McCall, a central Oregon ranch along the Crooked River near Prineville, and that is where Tom grew up.

In 1936, Tom McCall graduated from the University of Oregon with a journalism degree. He worked as a sportswriter in Idaho and as a reporter for the Oregonian and a radio news announcer for KGW in Portland before serving in the U.S. Navy during World War II. After the war, he returned to Portland to take a job as a radio host for his own news show on KEX. His flair for language and his distinctive voice—influenced by his parents’ Boston accents—became his trademarks.

McCall was inspired to enter politics by the career of his other grandfather, Samuel Walker McCall, who had been a Massachusetts congressman and governor. In 1949, he left his radio job to work as secretary to Oregon Governor Douglas McKay. After returning to Portland radio in 1951, he ran for Congress, challenging an eight-term incumbent, U.S. Representative Homer Angell, in the 1954 Republican primary. McCall’s upset victory over Angell primed him as a rising political star, but in November he lost a bitter general election race to Democrat Edith Green, a former teacher and union official. McCall blamed himself for allowing right-wing businessmen to manipulate him and his campaign message, and the loss taught him to value political independence.

McCall returned to broadcasting, this time in the emerging medium of television. As a commentator at KGW-TV in Portland, his candor and evenhanded analysis of public affairs earned him growing respect and popularity. McCall also produced landmark documentaries, including Farewell at Celilo in 1959 and Crisis in the Klamath Basin in 1958, which examined the fight over southern Oregon timberlands controlled by the Klamath tribe. In 1962, he co-wrote and anchored Pollution in Paradise, an hour-long documentary on unchecked industrial pollution, especially in the waste-choked Willamette River. The documentary shocked Oregonians, who had never seen such a visceral depiction of the state’s pollution or known its harm to the state’s economy. The documentary inspired legislative reforms that gave the state the authority to shut down polluters, and it established McCall as a champion for what he called Oregon’s “livability.”

In 1964, McCall won election as Oregon secretary of state, and two years later he campaigned to replace outgoing Governor Mark O. Hatfield. In the general election, McCall faced State Treasurer Robert W. Straub, a Democrat and devoted environmentalist. Their debates, nicknamed the “Tom & Bob Show,” revealed more similarities than differences as each sought to persuade voters that he was most committed to protecting the state’s natural resources. McCall won the race with 55 percent of the vote.

During his first term as governor, McCall championed protections for Oregon’s beaches, which were facing threats from private development. He denounced anyone (including fellow Republicans) who stood in the way of protecting the beaches, and lawmakers passed the 1967 Beach Bill as a bulwark against coastal development. McCall also threatened to close polluting mills, and in 1969 won legislative approval to establish the Department of Environmental Quality to enforce stronger standards.

McCall struggled as chief executive, and his first term saw political setbacks. An early advocate for prison reform, his administration mishandled management of the Oregon State Penitentiary. Prisoners rioted in March 1968, taking guards as hostages and burning several buildings. The riot ended with the hostages unharmed after McCall fired the warden and conceded to prisoners’ demands for better conditions. He considered the riot to be the single biggest disgrace during his time as governor.

In 1970, McCall sought re-election in a tough rematch against Straub. That summer, the FBI warned McCall that Vietnam War protestors planned a confrontation in Portland during the national American Legion convention in September, only weeks before election day. Most state and local leaders advocated for tough police action against protestors, but McCall preferred another approach. He opened Milo McIver State Park in Estacada, twenty-five miles southeast of Portland, for a government-sanctioned rock festival. Forty thousand people swarmed the festival, known as Vortex I. McCall’s bold political gamble paid off, and the Legion convention and anti-war protests went off in Portland without incident. He easily won re-election.

The victory emboldened him. In January 1971, McCall told a national television audience that Oregon was willing to protect its beauty and livability even if it meant controlling growth and discouraging newcomers. “Come visit us again and again,” he said. “But for heaven’s sake, don’t come here to live.” His statement—shorthanded as “Visit but don’t stay”—made international headlines and defined Oregon for years. McCall denied he was making the state inhospitable and said he was underscoring Oregon’s new efforts to manage growth. Critics later blamed McCall’s message for frustrating the state’s economic development.

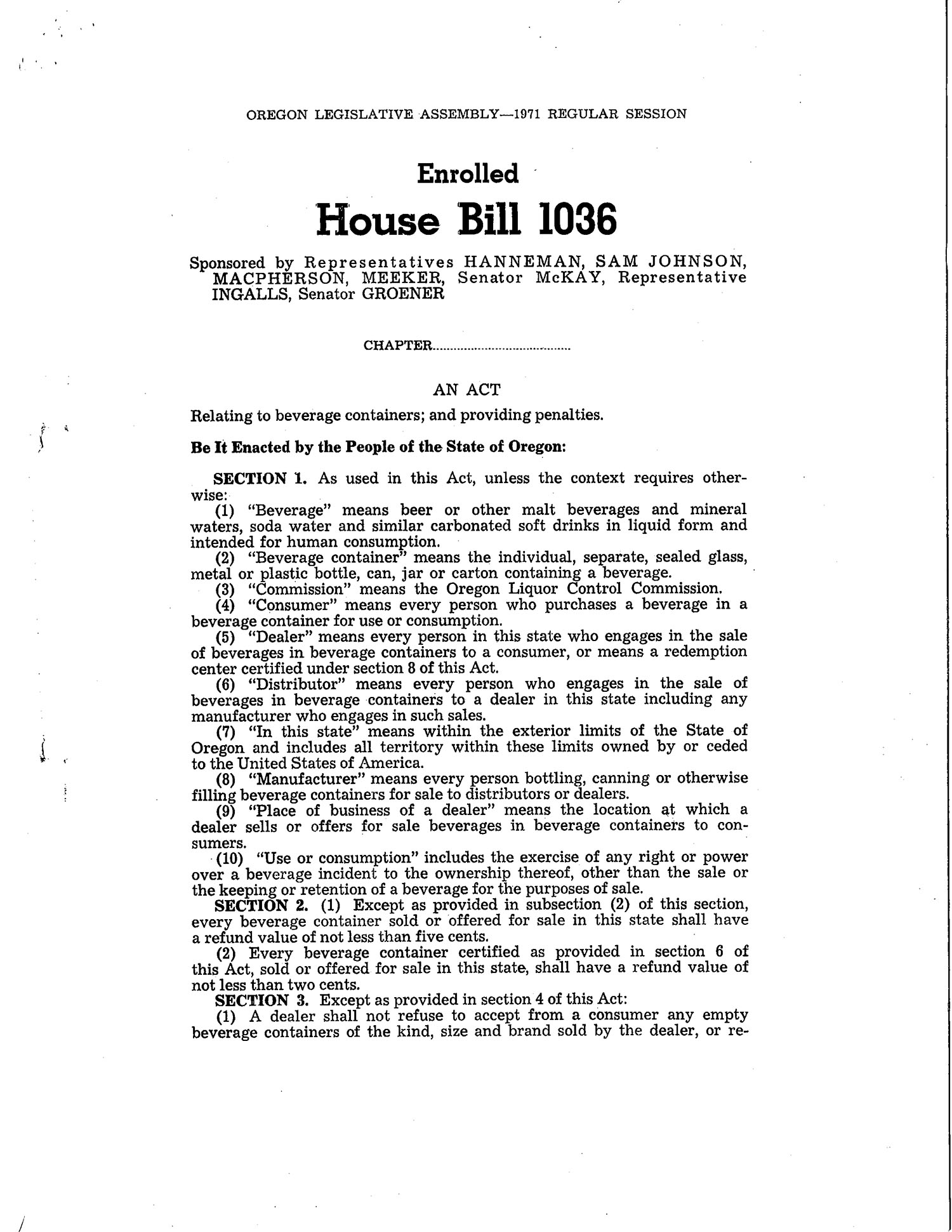

In 1971, McCall led the successful fight for the Oregon Bottle Bill, which became the nation’s first mandatory container deposit law. The bill overcame fierce opposition from beverage manufacturers who would be required to impose a five-cent deposit on cans and bottles. McCall and the bill’s other supporters first championed the idea as an anti-littering law, but he soon saw its potential to promote recycling and conservation and to end what he called the national “no-deposit, no-return ways of waste.”

When the nation faced energy shortages in 1973 and 1974, McCall told businesses to shut off commercial lights. Gas shortages created long lines at Oregon service stations, and the governor ordered an “odd/even” gas rationing plan—a vehicle could get fuel only on odd- or even-numbered days, depending on the last digit of its license plate. As governor, he lacked the legal authority to enforce these measures, but for the most part Oregonians complied. His outspoken advocacy for energy conservation helped create the foundation for the sustainability movement.

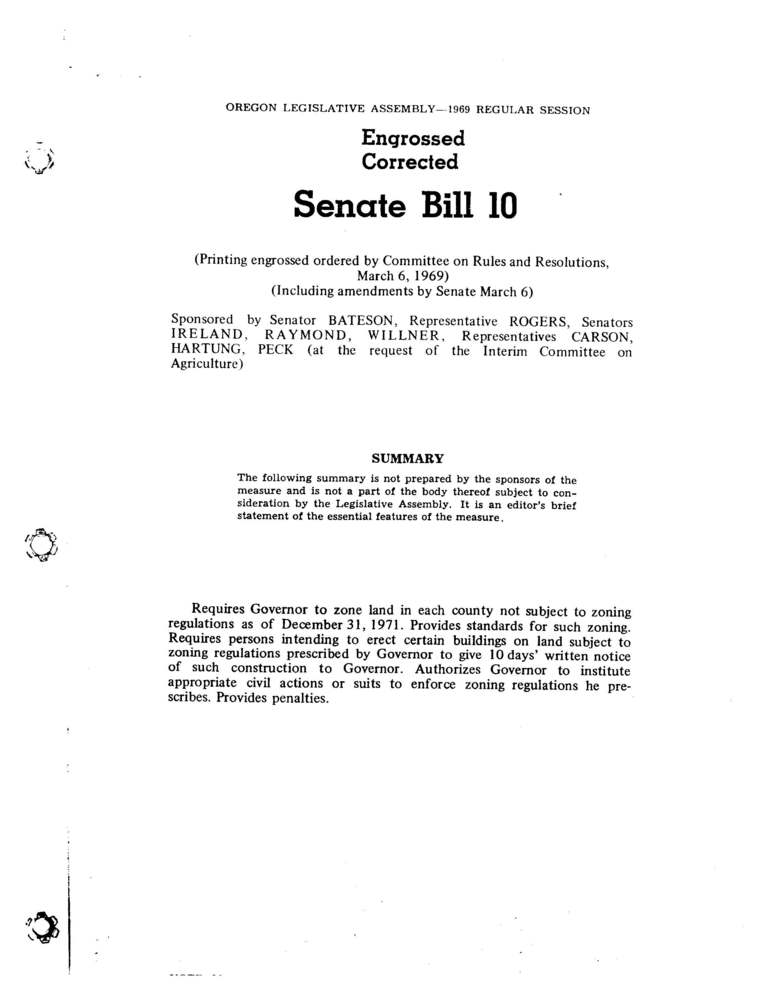

McCall’s most ambitious and enduring success was the creation of statewide land-use planning. In a January 1973 speech that defined his tenure as governor, McCall warned against the “shameless threat” from “sagebrush subdivisions, coastal ‘condomania,’ and the ravenous rampage of suburbia in Willamette Valley.” The 1973 legislature passed Senate Bill 100, a landmark law that established statewide goals for planning and development.

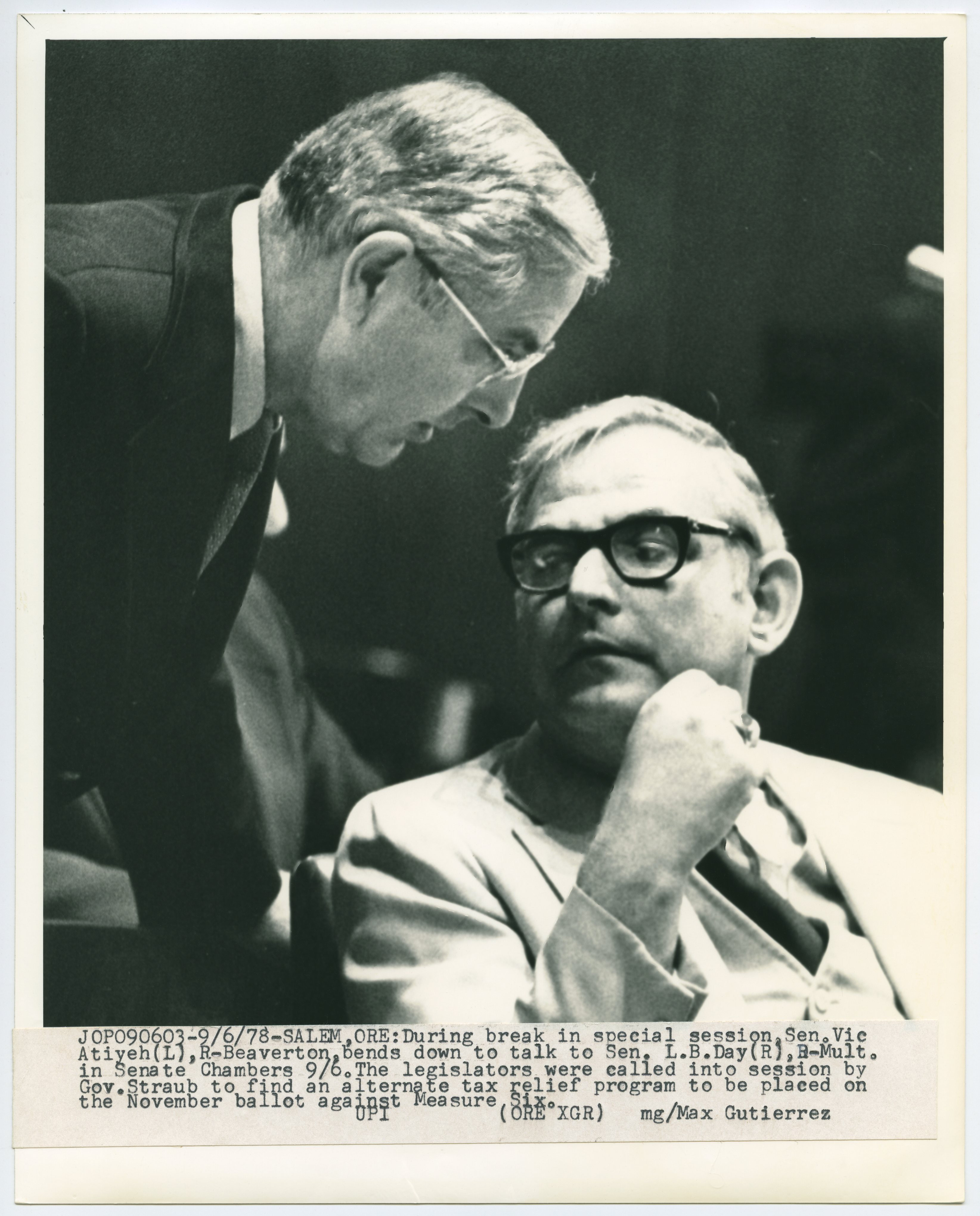

Forced from office by term limits, McCall returned to television in 1975 as a commentator at KATU. In 1978, he sought to reclaim his former office, running as a Republican even though he felt alienated from an increasingly conservative GOP. State Senator Vic Atiyeh, a Republican from Beaverton, defeated him in the primary, ending McCall’s political career.

In 1980, the Oregon economy collapsed under a crushing recession, the worst since the Great Depression. The state’s primary economic engine, the timber industry, lost 25 percent of its jobs. The causes of the recession ran deep, but critics tried to blame McCall’s anti-growth policies and promoted a 1982 ballot measure that would repeal statewide land-use planning. A frail McCall—he had been diagnosed with terminal cancer—spent his final months fighting Ballot Measure 6. Oregonians listened, and voters in November 1982 upheld the land-use planning he had helped put in place.

McCall died in Portland on January 8, 1983. In the following years, McCall’s stature and reputation grew. The city of Portland named Waterfront Park along the Willamette River in his honor, and a twenty-foot bronze statue of McCall stands along the river in Salem. His legacy is alive in the enduring debate Oregonians have over protecting the state’s livability through wise planning. McCall’s style, vision, and success have become the standard against which other Oregon leaders have since been measured.

-

![]()

McCall in the Navy.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![]()

McCall campaigning in Roseburg, Aug. 1966.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 1335

-

![]()

Tom McCall.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 1335

-

![]()

McCall (left) fishing on the Crooked River, 1925.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi97326

-

![]()

McCall interviewing Robert Kennedy during vice commission hearings, c.1956.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi97325

-

![]()

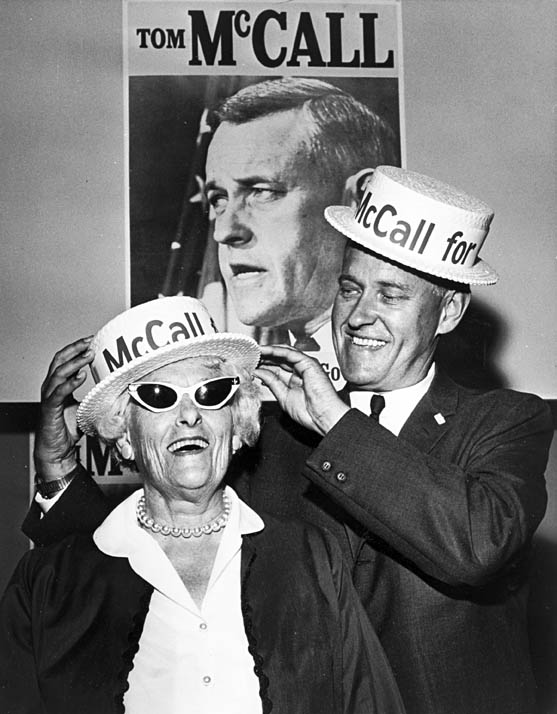

Audrey and Tom McCall, 1966, after successful campaign.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 1335

-

![]()

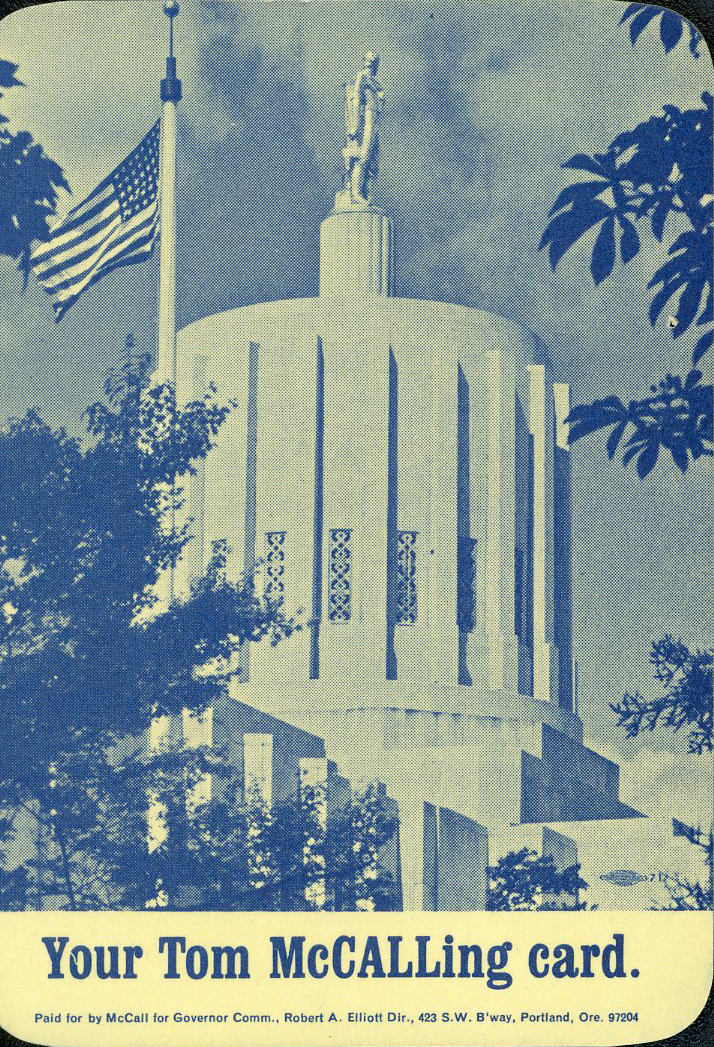

McCall governor campaign card.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss1513

-

![]()

Journalist Tom McCall on camera.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 1335

-

![]()

Oregonian news staff, McCall in back center-right; Earl Snell in center.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![Other guests were Robert Duncan, Anthony Yturri, and F.F. Montgomery]()

Boivin, second from left, on Tom McCall's KGW-TV show, Viewpoint, 1961.

Other guests were Robert Duncan, Anthony Yturri, and F.F. Montgomery Courtesy Oregon Hist. Society Research Lib., Oregon Journal, 012491

-

![]()

Douglas McKay, 1952.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 012518

-

![]()

Pres. Eisenhower greets McCall after 1954 primary win over Angell.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![]()

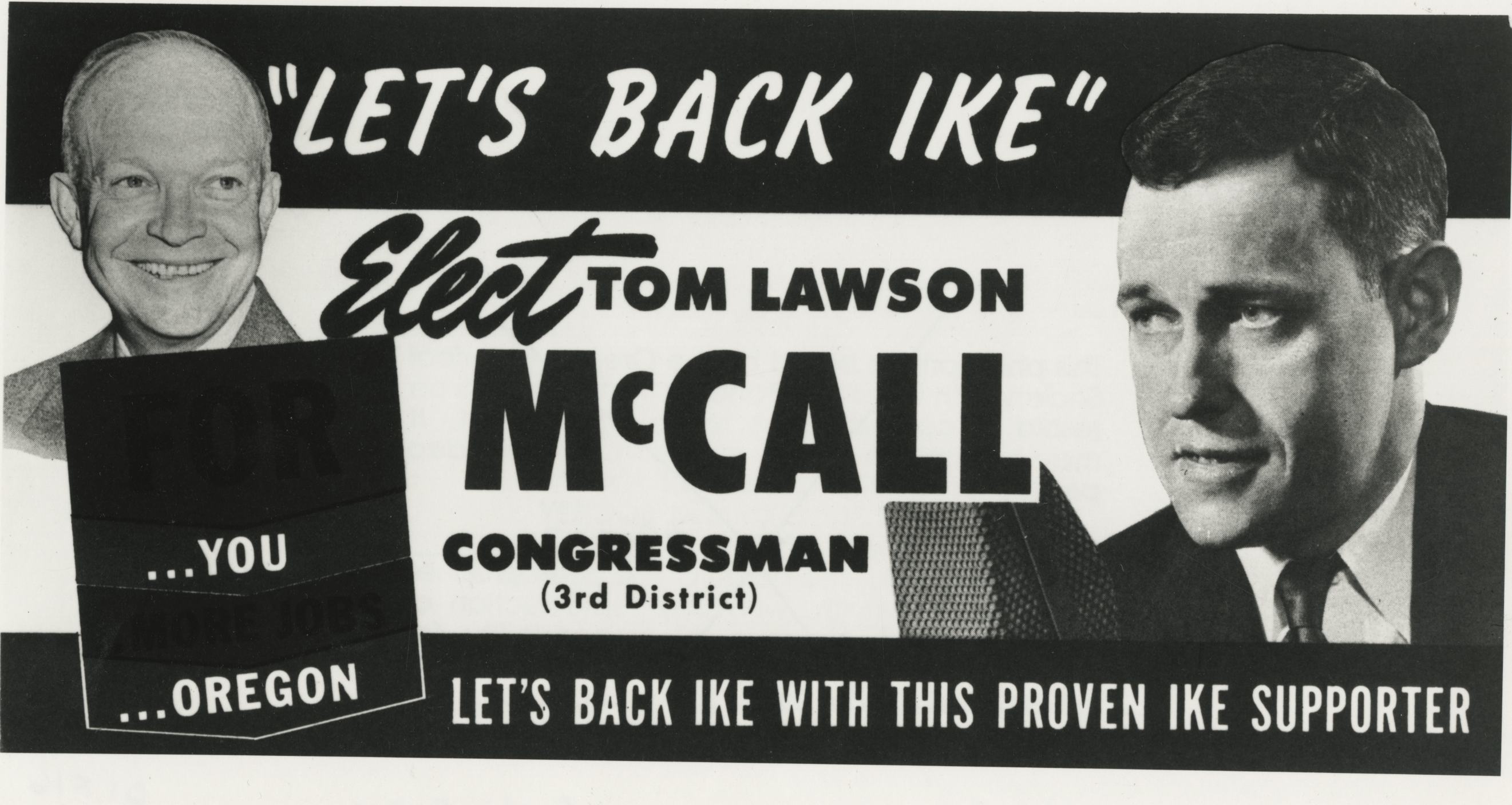

McCall's congressional campaign, 1954.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![]()

McCall concedes to Edith Green, Nov. 1954.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 37444

-

![]()

Secretary of State campaign mailer.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi090805

-

![]()

McCall campaigning on the Willamette river, 1964.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![Monte Ballou and the Castle Jazz Band]()

The opening of the Secretary of State campaign headquarters in Portland, 1964.

Monte Ballou and the Castle Jazz Band Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![]()

Secretary of State McCall at a press conference, 1966.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi90703

-

![]()

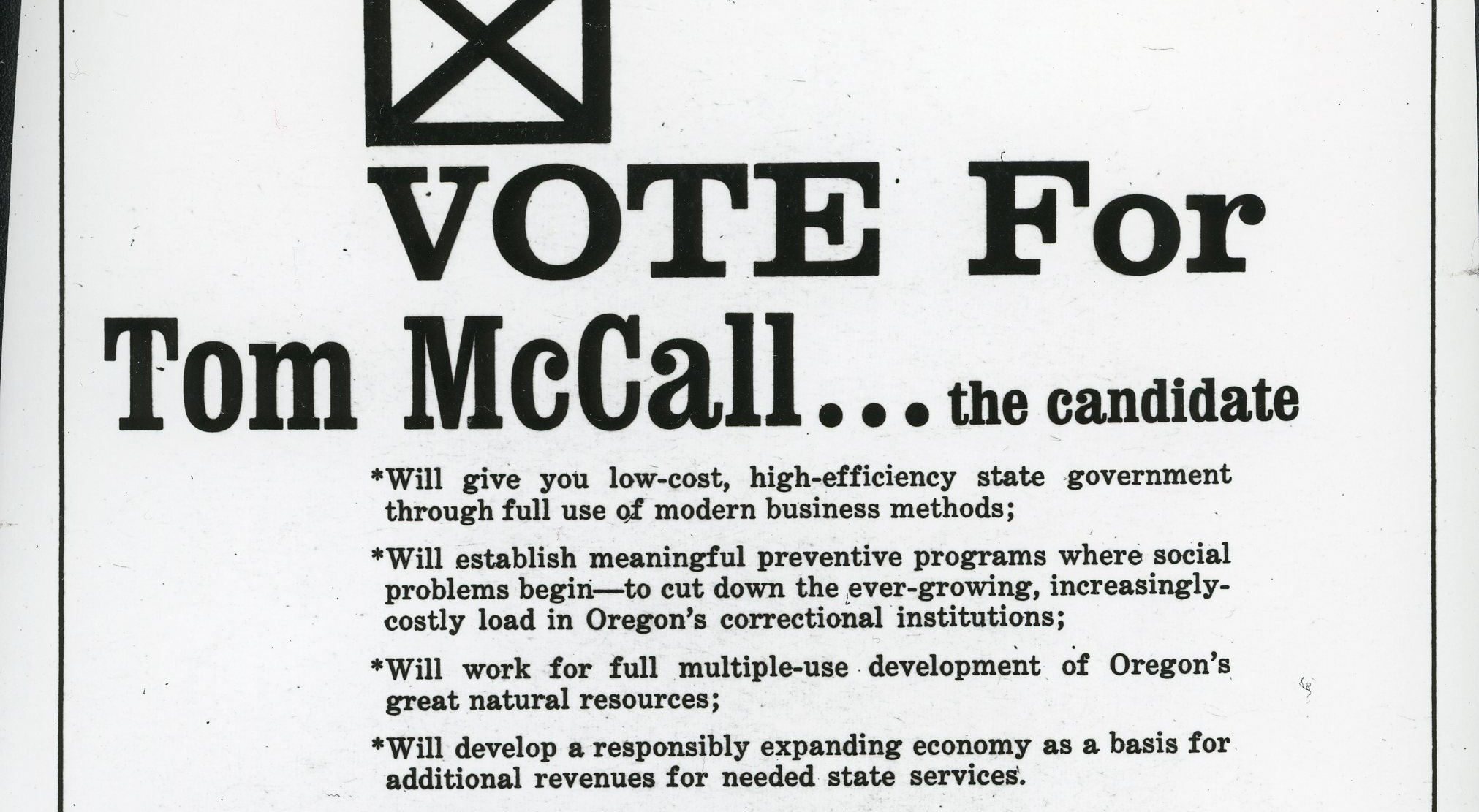

McCall campaign sticker.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Mss1513

-

![]()

McCall campaign event, c1966.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![]()

McCall campaigning in c.1966.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 1335

-

![]()

McCall campaigning for governor, 1966.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi97349

-

![]()

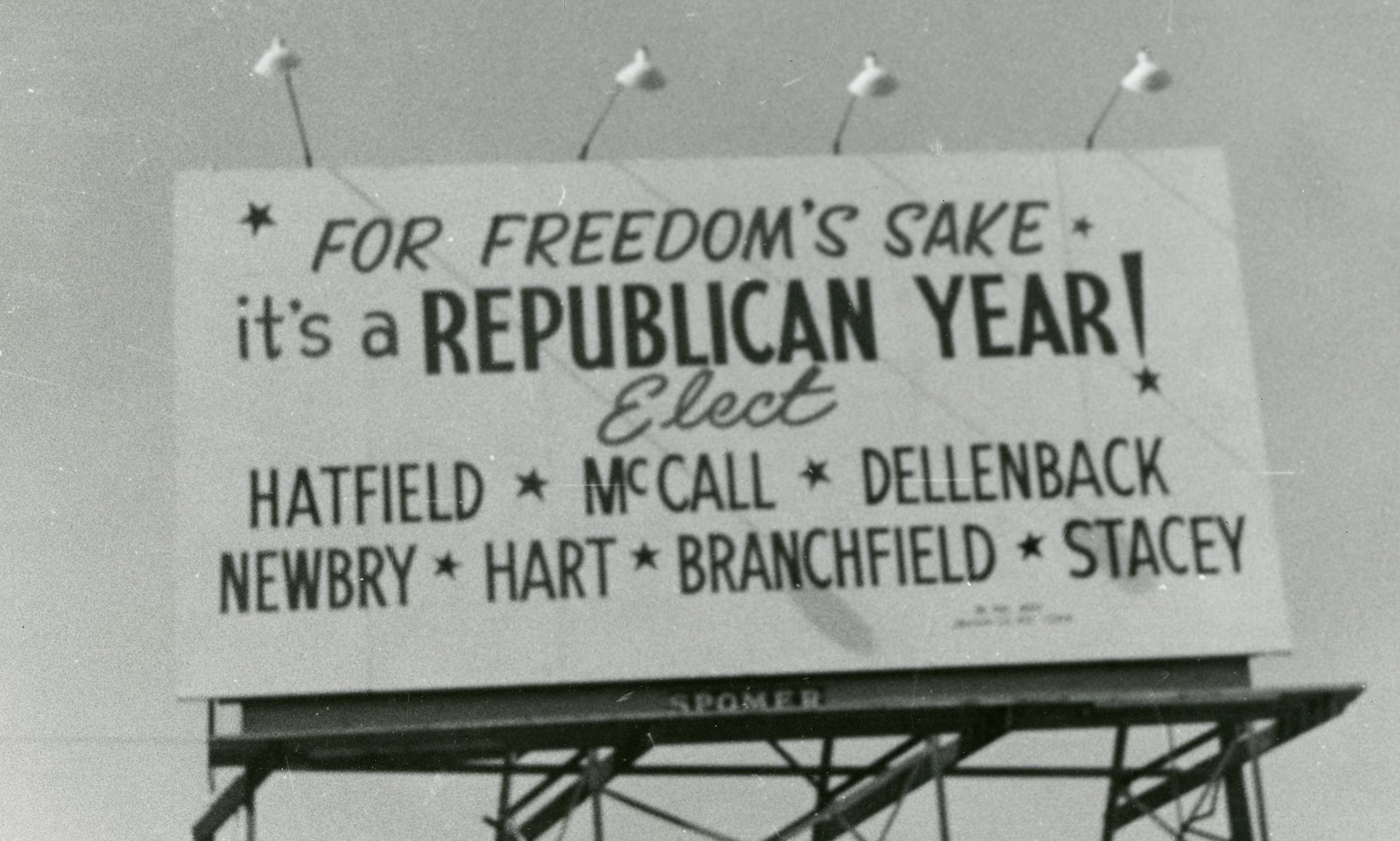

Campaign billboard near Medford, 1966.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 1335

-

![]()

Audrey and Tom McCall, 1966.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 1335

-

![]()

McCall and Nixon, 1954, at an Oregon masonic temple.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![]()

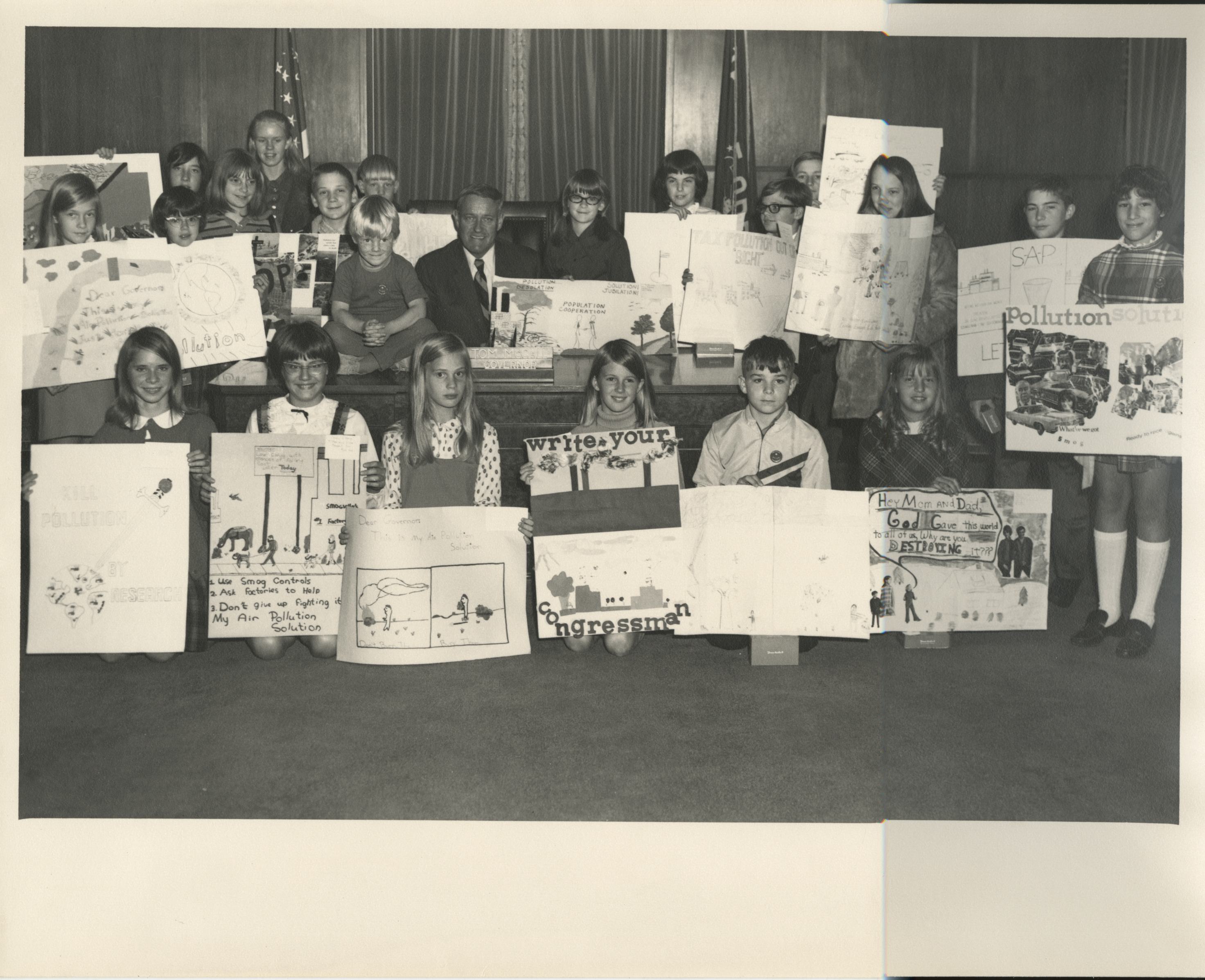

Beaches are for Kids event, 1968.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![]()

McCall in a helicopter flying over Oregon beaches, 1967.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., ba17646

-

![]()

First beach cleanup day, possibly Seaside..

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![]()

McCall meeting with the Willamette Oregon Council of the Blind.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![]()

McCall working from his hospital bed, Aug. 1, 1973.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![Governor Jimmy Carter sits in the front row.]()

McCall on Meet the Press, 1974, to talk about Watergate.

Governor Jimmy Carter sits in the front row. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![]()

McCall dedicating the Oregon Friendship Forest in Israel, 1973.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![]()

McCall greets Bob Hope.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 1335

-

![]()

McCall with Sam, Tad, and Audrey, 1967.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi97357

-

![]()

Tom and Audrey at son Tad's wedding to Barbara Jean Pyle, 1971.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 1335

-

![]()

Dorothy McCall with Tom at a book signing.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![]()

McCall and Howard Lane fishing, 1970.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![]()

McCall at an unknown Vikings-themed event.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 1335

-

![]()

McCall participating in a Grants Pass Cavemen event .

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 1335

-

![]()

Audrey and Tom McCall, 1964, following Sec. of State win.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 1335

-

![]()

Audrey and Tom McCall.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![]()

Tom and Audrey McCall.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

-

![]()

Tom and Audrey McCall, 1981, following Tom's hospital stay.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 353

Related Entries

-

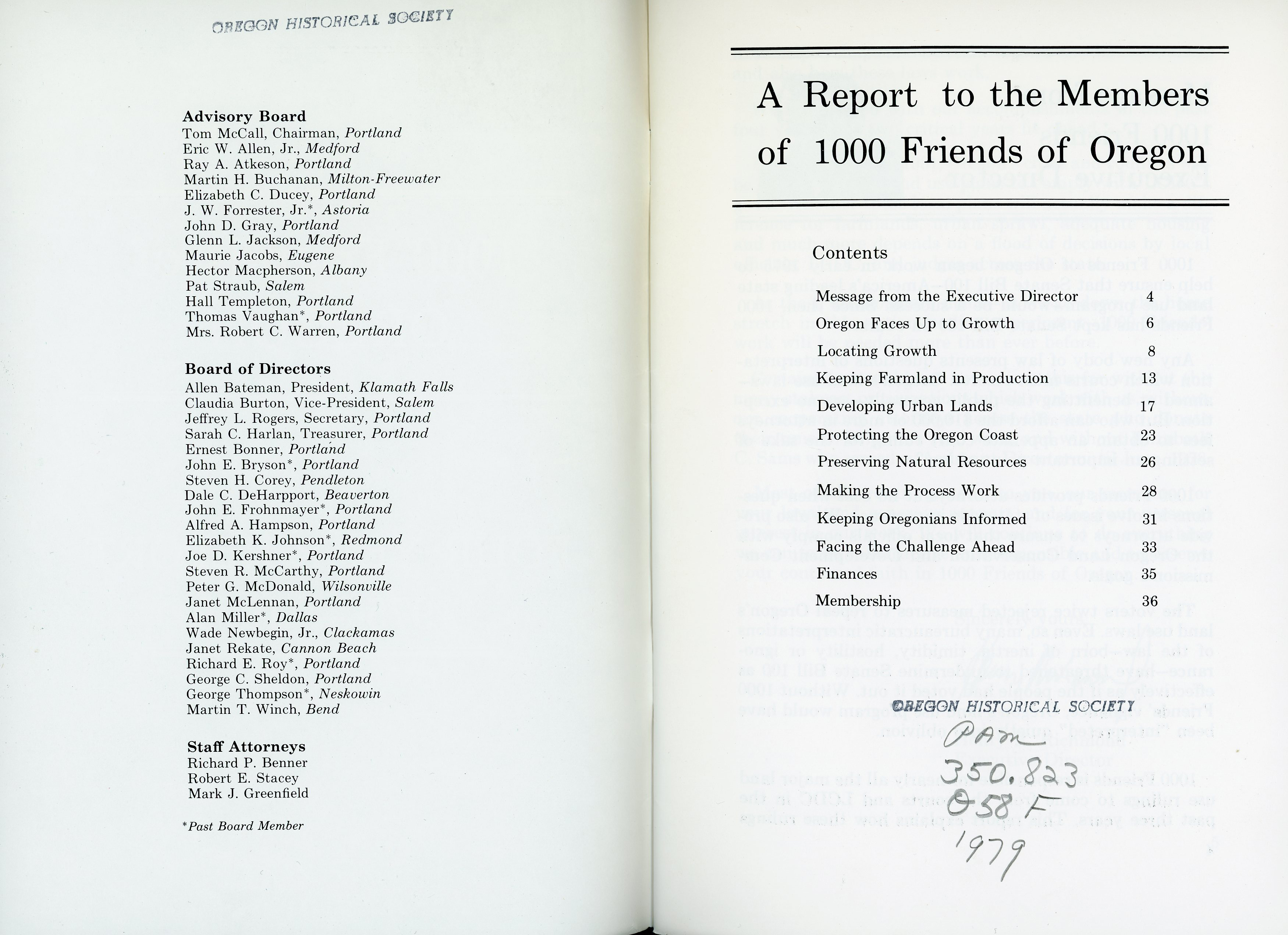

![1000 Friends of Oregon]()

1000 Friends of Oregon

1000 Friends of Oregon was founded in 1975 by Governor Tom McCall and a…

-

![Beverage Container Act (Bottle Bill)]()

Beverage Container Act (Bottle Bill)

The Oregon Beverage Container Act of 1971, popularly called the Bottle …

-

![Crisis in the Klamath Basin (documentary film)]()

Crisis in the Klamath Basin (documentary film)

The 1958 KGW-TV documentary Crisis in the Klamath Basin broke important…

-

![Department of Environmental Quality]()

Department of Environmental Quality

The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) administers and en…

-

![Dorothy Lawson McCall (1888-1982)]()

Dorothy Lawson McCall (1888-1982)

Dorothy Lawson, mother of Oregon Governor Thomas Lawson McCall, was bor…

-

![Hector Macpherson (1918-2015)]()

Hector Macpherson (1918-2015)

Hector Macpherson Jr. received the Distinguished Leadership Award for a…

-

![L. B. Day (1932-1986)]()

L. B. Day (1932-1986)

L.B. Day was one of a handful of political giants who played leadership…

-

![Operation Red Hat]()

Operation Red Hat

Operation Red Hat was the label the American military applied broadly t…

-

![Oregon Beach Bill]()

Oregon Beach Bill

Oregonians struggling to maintain public access to Pacific Ocean beache…

-

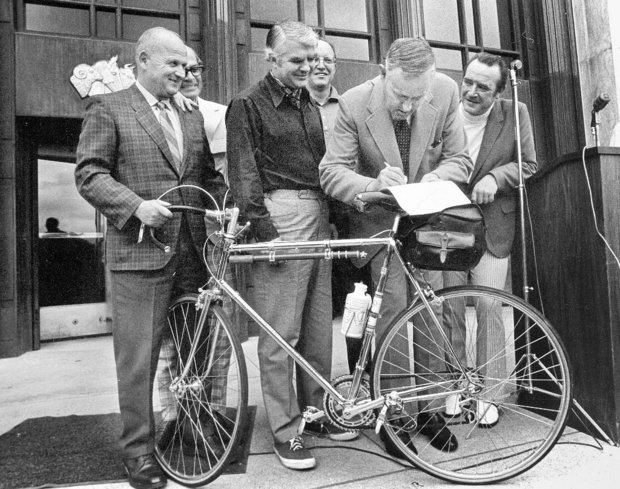

![Oregon Bicycle Bill]()

Oregon Bicycle Bill

On June 11, 1971, Governor Tom McCall, with his usual flair for publici…

-

![Pollution in Paradise (documentary film)]()

Pollution in Paradise (documentary film)

KGW-TV aired Tom McCall’s one-hour documentary Pollution in Paradise on…

-

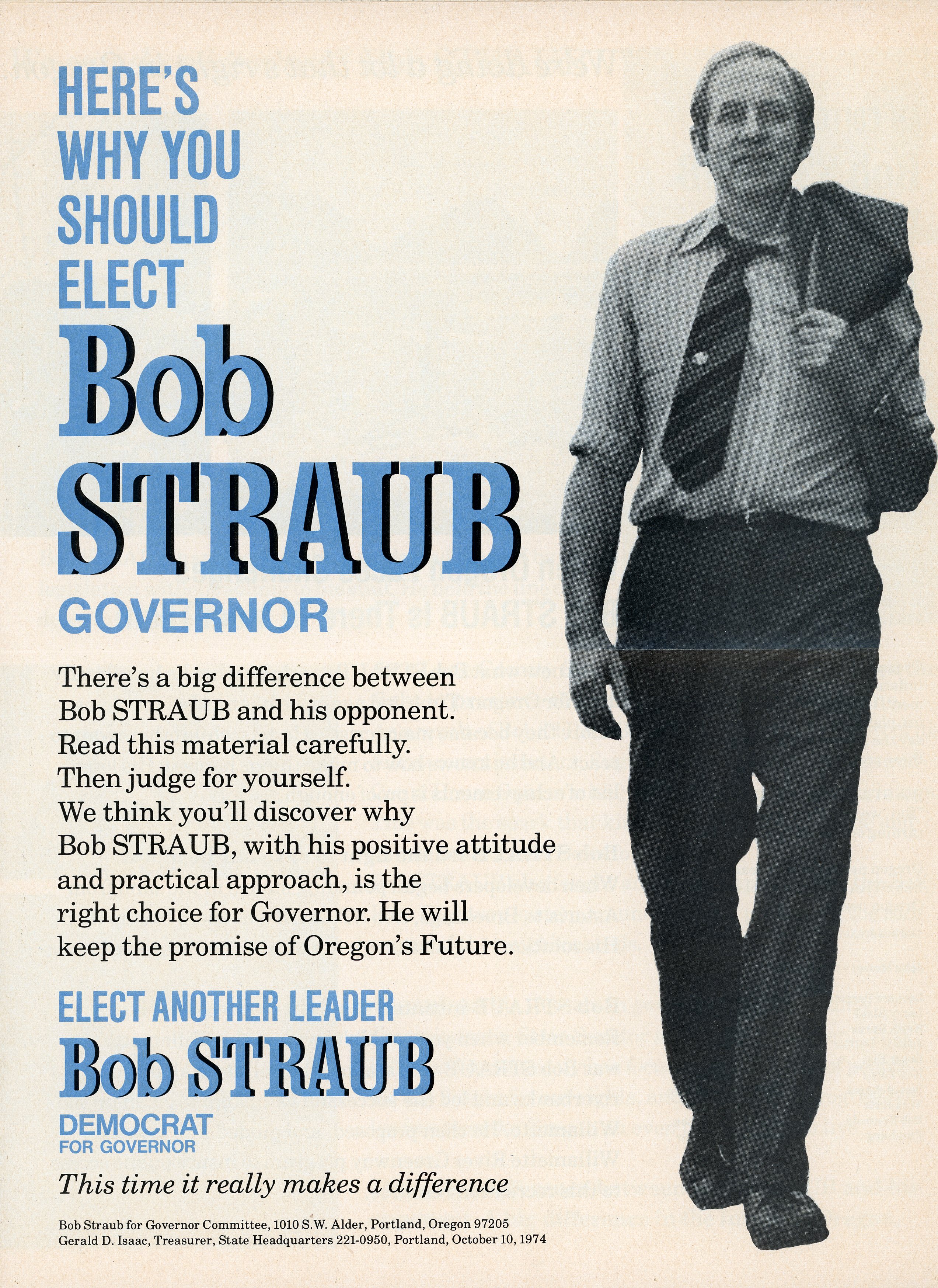

![Robert Straub (1920-2002)]()

Robert Straub (1920-2002)

Robert W. Straub, Oregon’s thirty-first governor, was a plainspoken pol…

-

![Senate Bill 100]()

Senate Bill 100

Signed into law on May 29, 1973, Oregon Senate Bill 100 created an inst…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

McCall, Tom, and Steve Neal. Tom McCall: Maverick. Portland: Binford & Mort, 1977.

Tom McCall Papers. Mss 625, Oregon Historical Society, Portland.

Tom McCall Photo Collections. Org. Lot. 353, Oregon Historical Society, Portland.

Dorothy Lawson McCall Papers. Mss1393, Oregon Historical Society, Portland.

Interview with Governor Tom McCall, by Steve Lorton. Sound recording. SR298, Oregon Historical Society, Portland.

Penwell Collection. Org Lot 1335, Oregon Historical Society, Portland.

Logan, Robert K. The Oregon Land Use Story. Salem: Oregon Local Government Relations Division, 1974.

Plotkin, Sidney. Keep Out: The Struggle for Land Use Control. BerkeleyL U. of California Press, 1981.

Liberty, Robert. “The battle over Tom McCall’s legacy: the story of land use in the 1995 Oregon legislature.” Pamphlet. Portland: 1000 Friends of Oregon, 1995.