"Multnomah" is a word familiar to Oregonians as the name of a county and a waterfall, among other places. Less well known is its origin as the name of an Indian village once located on the upriver end of Sauvie Island facing the Columbia River. The name is from Chinookan máɬnumax̣ (also nímaɬnumax̣) ‘those toward water’ (or ‘toward the Columbia River’, known in Chinookan as ímaɬ or wímaɬ ‘the great water’).

First mentioned by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, who saw the village in November 1805 as they descended the Columbia, Multnomah was one of a number of villages in what the expedition captains called the Wappato Valley, from the abundance of wapato (Sagittaria latifolia) growing in an area reaching from about the Lewis River to about Government Island. Earlier, however, Multnomah may well have been the unnamed village contacted by members of the Vancouver expedition in 1792, to judge by the location.

When Lewis and Clark saw the Multnomah village, they estimated the population to be some two hundred people, an estimate they changed to eight hundred after seeing it again in late March 1806 on their return upriver. The change probably reflected an influx of people seeking wapato and other resources available in the valley in spring. When the Astorian fur hunter Robert Stuart saw Multnomah in 1812, he estimated the place to have some five hundred people, as he reported later to Jedediah Morse.

It is rare to find the people themselves mentioned, but another Astorian, Alfred Seton, said of the village that it was "famous...among our voyageurs for the fat dogs the old squaws always provided." (Apparently, the Astorians, as well as Lewis and Clark earlier, had learned to eat dogs.) And at Fort Astoria in September 1813, there were “Seven Canoes of Multnomah people trading Beaver, dressed Deer Skins, dried Salmon.”

In the early 1830s, a devastating epidemic of malaria swept the Columbia, hitting the Wappato Valley especially hard. The very few survivors on Sauvie Island must have fled. One may have been Marie Mathlomet, age twenty-two, who was baptized and married in 1839. (In the Catholic records, which recorded her name as "Mathlomet by nation," Indian women's original places of origin were often used as surnames.) Only the dead remained in Multnomah, and the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Vancouver ordered the corpses burned. Most of the village washed away, according to Emory Strong, author of Stone Age on the Columbia River (1959). "It is now covered by a farmstead." Artifacts from the site are now in private hands.

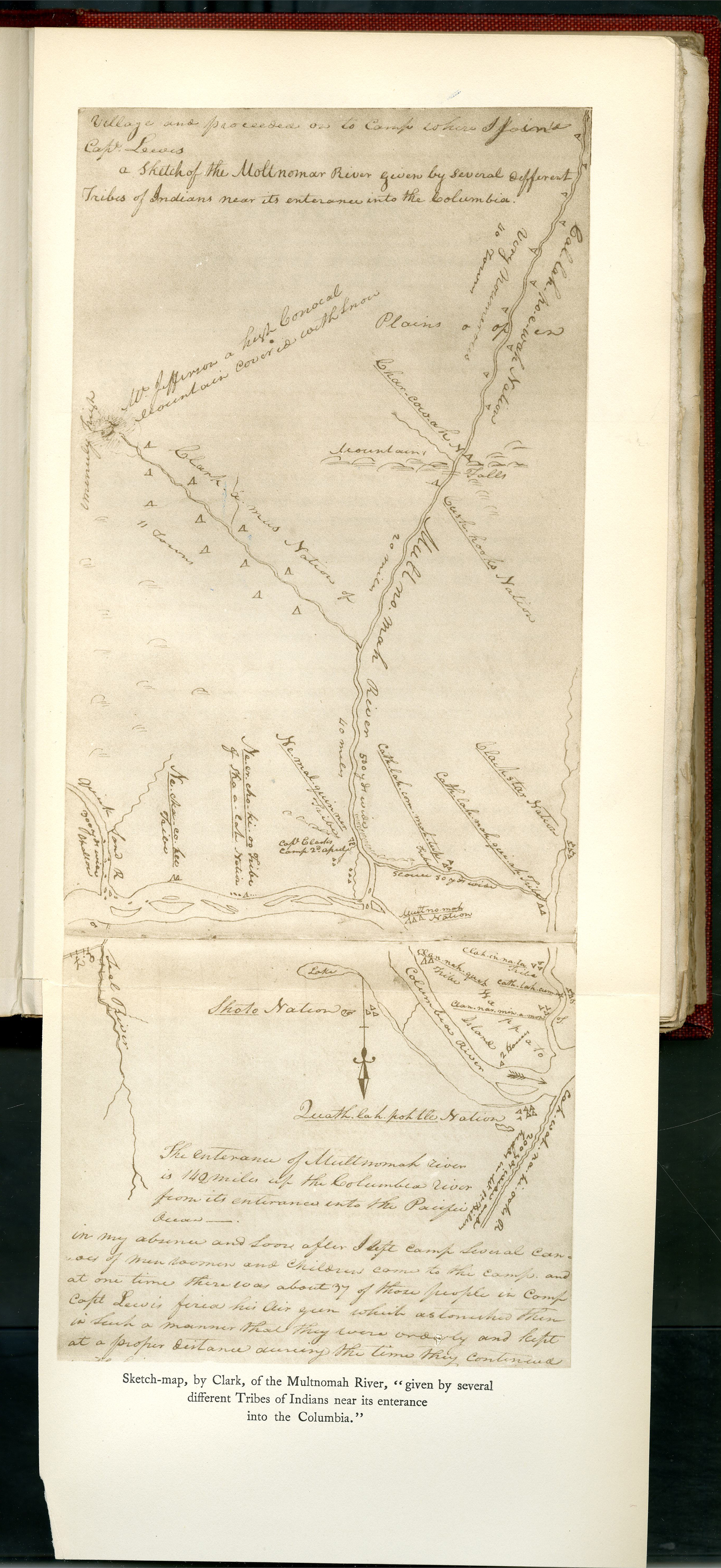

Early on, "Multnomah" referred to an area larger than the original village. In 1811, the Astorian Gabriel Franchère referred to two Multnomah villages. Alfred Seton, a clerk for the Pacific Fur Company, extended the name to Sauvie Island, calling it Multnomah Island, as missionary Samuel Parker and others did later. Lewis and Clark had applied "Multnomah" to what is now called the Willamette River (Clark's map shows the Mult-no-mah River as originating in the vicinity of the Great Salt Lake.) They provided what might be a partial explanation for the persistence of the name: “All the tribes in the neighbourhood of Wappatoo island, we have considered as Multnomahs, not because they are in any degree subordinate to that nation; but they all seem to regard the Multnomahs as the most powerful."

The popular association of the name with an allegedly historical "Chief Multnomah" goes back to Frederick Balch's The Bridge of the Gods (1890), a local exemplar of the Victorian "Indian romance" literary genre. Balch's Chief Multnomah may have been inspired in part by the historical figure of Kiesno, a prominent Wappato Valley chief, but Balch's epic is not to be taken as reliable history.

Although the village is long gone, its name persists. Today, "Multnomah" is applied to the dialect of Chinookan presumably spoken in the Wappato Valley, and sometimes to the valley itself. It signifies a county, a waterfall, a neighborhood of Portland, and streets, businesses, and organizations in Oregon. While the village is no more, the name lives on.

-

![]()

Sauvie Island and Multnomah Channel, aerial.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Org Lot 672

-

![]()

Owl sculpture, Sauvie Island.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Museum, OrHi37732

-

![Click on documents tab to see longer journal entry on Lewis and Clark's observations.]()

Account of Sauvie Island and inhabitants.

Click on documents tab to see longer journal entry on Lewis and Clark's observations. Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib.

-

![]()

Estimate of Western Indians, Lewis and Clark.

Courtesy American Philosophy Association, Philadelphia

Documents

Related Entries

-

![Camas]()

Camas

Camas is a North American bulb-forming geophyte whose greatest diversit…

-

![Disease Epidemics among Indians, 1770s-1850s]()

Disease Epidemics among Indians, 1770s-1850s

In 1972, historian Alfred Crosby introduced the term Columbian Exchange…

-

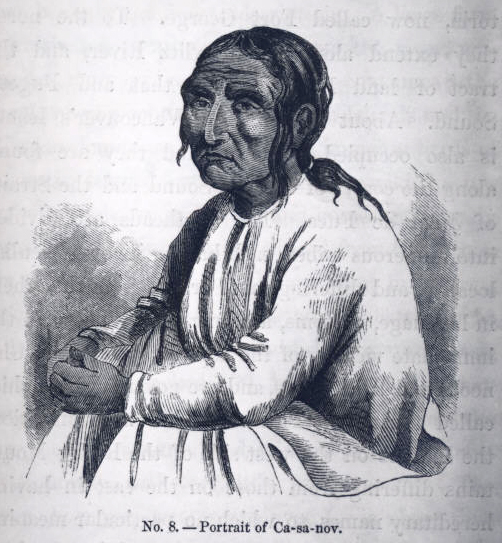

![Kiesno (Chief Cassino) (1779?-1848)]()

Kiesno (Chief Cassino) (1779?-1848)

Chief Kiesno (his name has also been spelled Keasno, Casino, Kiyasnu, Q…

-

![Lewis and Clark Expedition]()

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Expedition No exploration of the Oregon Country has greater histor…

-

![Native Art of the Wapato Valley]()

Native Art of the Wapato Valley

Sauvie Island, at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers,…

-

![Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the early 1800s]()

Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the early 1800s

During the early nineteenth century, upwards of thirty Native American …

-

![Wapato (Wappato) Valley Indians]()

Wapato (Wappato) Valley Indians

Lewis and Clark called them the "Wappato Indians," the people who inhab…

-

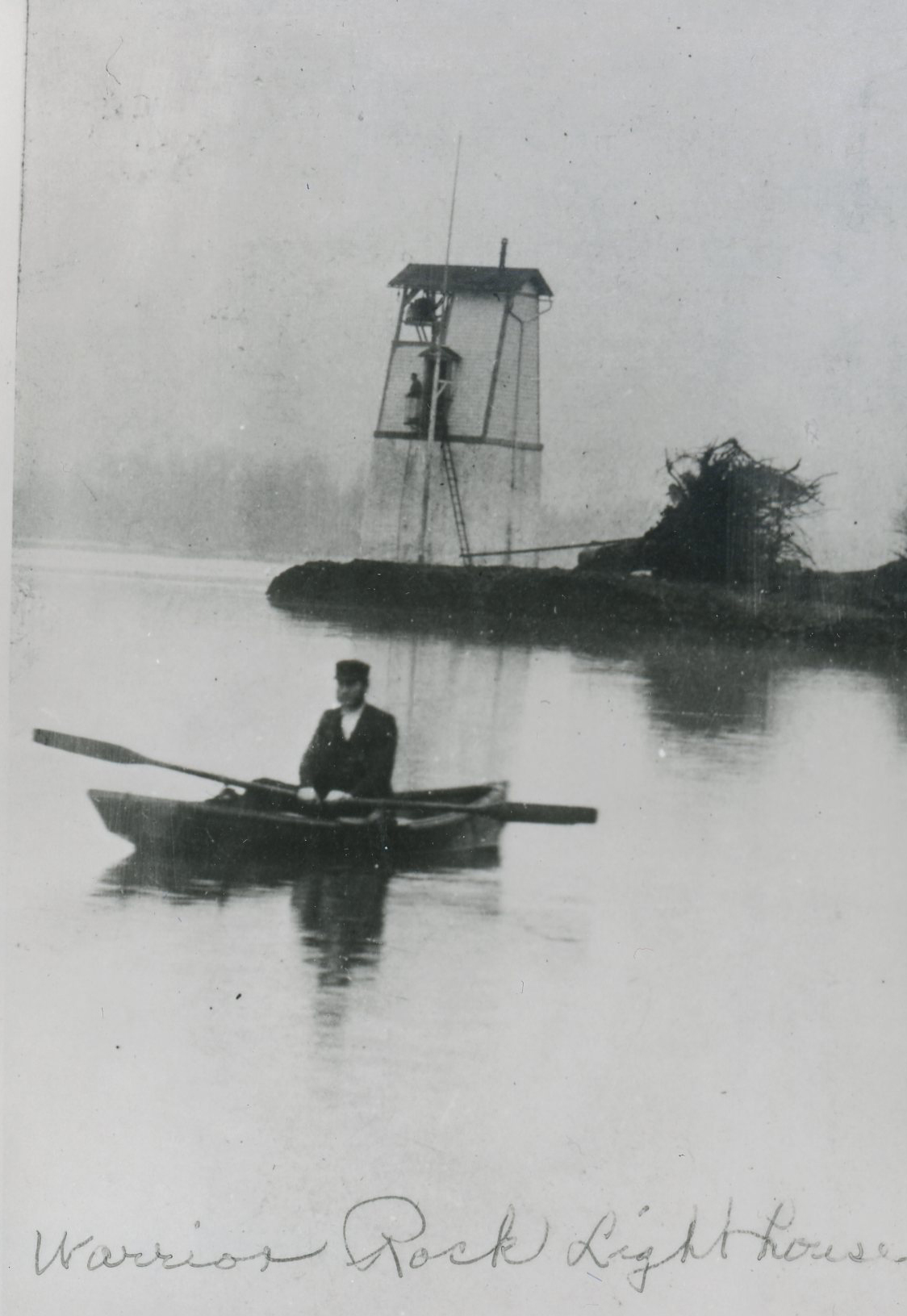

![Warrior Point]()

Warrior Point

Warrior Point, on the north end of Sauvie Island in the Columbia River …

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Balch, Frederick. Bridge of the Gods. Chicago, Ill. :McClurg and Co., 1890.

Bell, Edward. "Excerpt from Edward Bell's Journal." In J. Neilson Barry, Columbia River Exploration 1792. Oregon Historical Quarterly 33.1 (March 1932): 31-42.

Biddle, Nicholas. History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis and Clark. 2 vols. Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1814. Reprint, New York: AMS Press, 1973.

Franchere, Gabriel. Journal of a Voyage on the North West Coast of North America during the years 1811, 1812, 1813, and 1814. Translated by W. Kaye. Edited by Winnie Lamb. Toronto: Champlain Society, 1969.

Jones, Robert F., ed. Annals of Astoria. New York: Fordham University Press, 1990.

Lewis, Meriwether and William Clark. Definitive Journals of Lewis and Clark, vol. 6. Edited by Gary Moulton. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. 1990.

Morse, Jedediah. A Report to the Secretary of War of the United States on Indian Affairs, Comprising a Narrative of a Tour Performed in the Summer of 1820. New Haven, Conn.: S. Converse, 1822.

Munnick, Harriet. Catholic Church Records of the Pacific Northwest: Vancouver, vols. 1 and 2 (1838-1856), and Stellamaris Mission (1848-1860). St. Paul, Ore.: French Prairie Press. 1972.

Ogden, Peter. Traits of Indian Life and Character. San Francisco: Grabhorn Press, 1853. Reprint, New York: AMS Press, 1972.

Parker, Samuel. Journal of an Exploring Tour beyond the Rocky Mountains. Minneapolis, WI: Ross & Haines, 1963.

Seton, Alfred. The Journal of Alfred Steon. Edited by Robert P. Jones. New York: Fordham University Press, 1993.

Silverstein, Michael. "Chinookans of the Lower Columbia." In Northwest Coast, Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 7., edited by Wayne Suttles, 533-46. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution., 1990.

Strong, Emory. Stone Age on the Columbia. Portland, Ore.: Binfords and Mort, 1959.

Zenk, Henry, Yvonne Hajda, and Robert Boyd. "Chinookan Villages of the Lower Columbia." Oregon Historical Quarterly 117.1 (2016): 6-37.