In 1934, Oregon amended its constitution to allow for non-unanimous jury verdicts in criminal cases, excluding cases where a defendant is on trial for first-degree murder. That change to the state constitution made Oregon one of only two states (the other is Louisiana) that allowed non-unanimous jury convictions in criminal felony cases. All other states and the federal government require that jury verdicts be unanimous in such cases. Oregon voters approved a ballot measure amending the state constitution to allow the non-unanimous jury rule. In 2020, the U.S. Supreme Court, in Ramos v. Louisiana, banned non-unanimous jury verdicts in criminal cases in both federal and state courts. In 2022, the Oregon Supreme Court ruled in Watkins v. Ackley that the Ramos ruling applied retroactively.

The 1934 non-unanimous jury law evolved from the murder trial involving Jacob Silverman, a Portland hotel proprietor, who was charged with murdering Jimmy Walker near Scappoose in April 1933. During jury deliberations, eleven jurors wanted to find Silverman guilty of first-degree murder, and one did not. The jury compromised by finding him guilty of manslaughter. Many Oregonians were outraged at the less severe verdict. Less than a month after Silverman was sentenced, the Oregon legislature proposed a constitutional amendment authorizing non-unanimous jury verdicts.

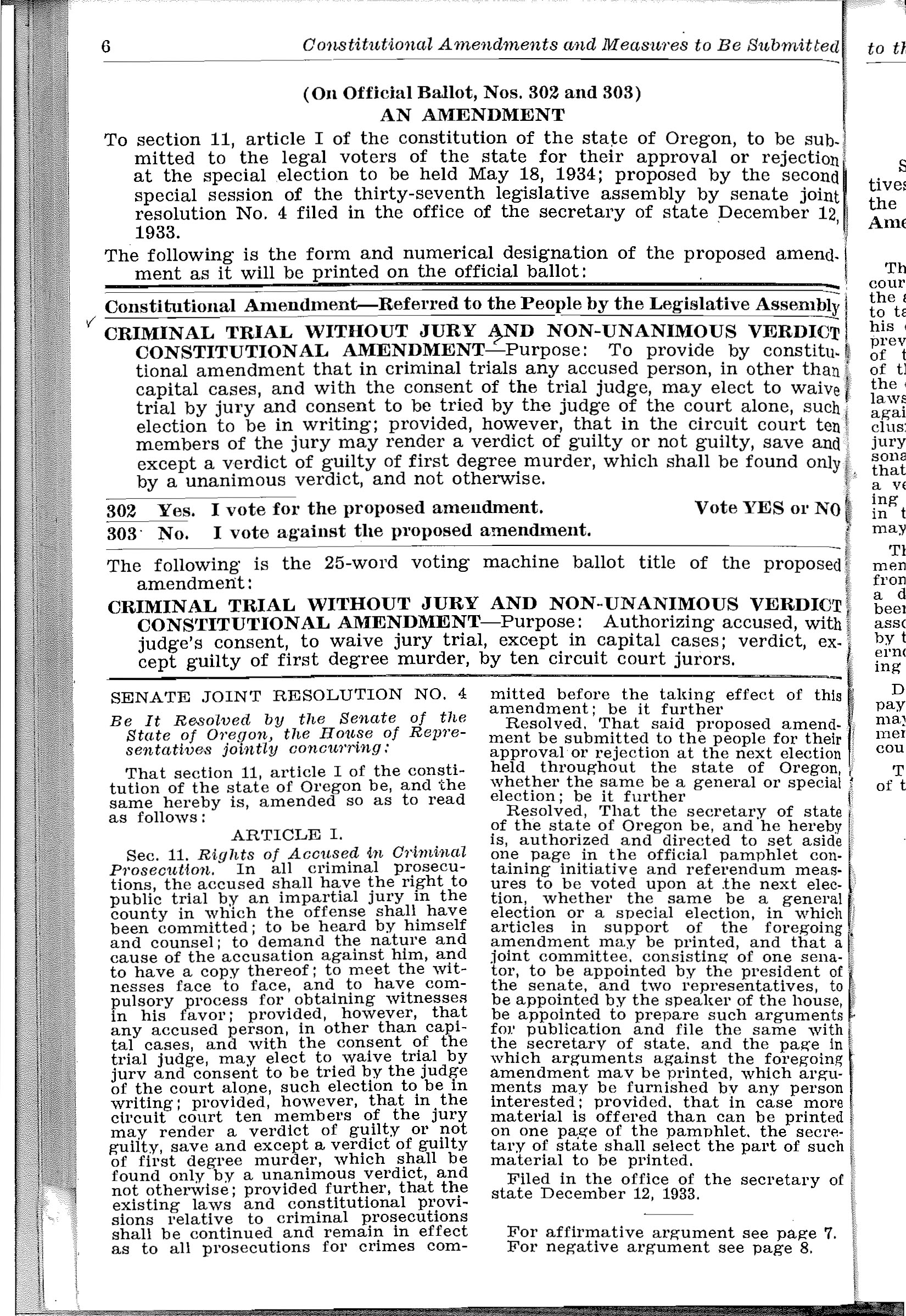

In the 1934 Oregon Voters’ Pamphlet, published by the Oregon Secretary of State’s office, advocates for the change argued that the constitutional amendment would “prevent one or two jurors from controlling the verdict or causing a disagreement,” results that can be costly to taxpayers and cause congestion in the courts. Local news outlets supported the amendment by claiming that hung juries were caused by corrupt jurors and untrained immigrants. “The increased urbanization of American life, and the vast immigration into America from southern and eastern Europe, of people untrained in the jury system,” the November 25, 1933, Oregonian editorialized, “have combined to make the jury of twelve increasingly unwieldy and unsatisfactory.”

The only argument against the amendment in the voters’ pamphlet noted the irony of excluding the most egregious crimes from being judged by a non-unanimous jury, which the writer cautioned would increase the likelihood of acquittal for first-degree murder. The writer also suggested higher pay for district attorneys, who supported the measure, in order to attract competent lawyers to the job.

Oregonians approved the amendment with 58 percent of the vote, adding to Article 1, Section 11 of the Oregon Constitution: “in the circuit court ten members of the jury may render a verdict of guilty or not guilty, save and except a verdict of guilty of first degree murder, which shall be found only by a unanimous verdict, and not otherwise.”

The Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guarantees rights to the accused in a criminal prosecution, including the right to a trial by jury, but it is silent as to whether a jury verdict must be unanimous. In 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court addressed the issue of non-unanimous juries in Duncan v. Louisiana, ruling that the right to a jury trial is a fundamental right to be incorporated against the states by the Fourteenth Amendment and that unanimity is a characteristic of that right. (The incorporation doctrine is a constitutional doctrine through which provisions of the Bill of Rights are made applicable to the states through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment).

Four years later, however, in Apodaca v. Oregon (1972) and Johnson v. Louisiana (1972), the U.S. Supreme Court declined to require unanimity in state criminal cases. In Apodaca, the Court held that state juries may convict a defendant by less than unanimity even though federal law requires federal juries to reach criminal verdicts unanimously. The opinion was split. Four justices found that the Sixth Amendment did not mandate unanimity, while four justices found that it did and that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporated the requirement against the states. Justice Lewis Powell, writing alone and deciding the outcome of the case, found that the Sixth Amendment required unanimity in federal cases but not in state cases.

The split court opinion was important, because it demonstrated that there was still debate over whether a non-unanimous jury verdict violates a criminal defendant’s constitutional rights. Advocates argued that all states, including Oregon, should be subjected to the unanimous jury requirement in accordance with the U.S. Constitution; it is a right provided by the Sixth Amendment, they noted, and ensures that the burden of proof beyond a reasonable doubt is met. They also argued that not only do non-unanimous jury verdicts infringe on Oregonians’ constitutional rights, but they also lead to the conviction of innocent defendants and disregard the viewpoint of minority jurors.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled on April 20, 2020, in Ramos v. Louisiana, that the Constitution banned non-unanimous jury verdicts in criminal cases, a decision that affects defendants and prisoners in Louisiana and Oregon. While there was never any dispute over whether the unanimous jury requirement applies to the federal government, the question in Ramos v. Louisiana was whether it applied to the states as well. A six-justice Supreme Court majority, made up of both conservatives and liberal justices, rejected the Apodaca decision and concluded that Justice Powell’s 1972 ruling had been a mistake. Justice Neil Gorsuch, writing for the majority, laid out the history behind the Oregon law. The adoption of the non-unanimous jury rule, he wrote, "can similarly be traced to the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and efforts to dilute the influence of racial and ethnic and religious minorities on Oregon juries."

Ramos left unanswered the question of whether it would apply retroactively to convictions determined before the decision was issued. The U.S. Supreme Court addressed that question in May 2021 in Edwards v. Vannoy. The Court held that under federal law the requirement for unanimous jury verdicts in serious criminal cases applied to new cases going forward and cases currently on appeal; it did not require the reversal of criminal convictions finalized prior to the Ramos decision. Edwards clarified, however, that states were not bound to follow federal law and could pass laws that would apply the Ramos decision retroactively.

In July 2021, the question of whether Ramos should apply retroactively under state law was certified to the Oregon Supreme Court. On December 30, 2022, the Oregon Supreme Court ruled in Watkins v. Ackley that the prohibition on non-unanimous convictions established by Ramos applies to all such convictions in Oregon, including those finalized before the Ramos ruling in April 2020. Based on Watkins, those convicted by a non-unanimous jury verdict can bring a claim to have their conviction reversed.

-

![]()

Voter pamphlet, 1934.

Courtesy Oregon State Library

Related Entries

-

![14th Amendment]()

14th Amendment

The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution declared that the fed…

-

![Death with Dignity Law]()

Death with Dignity Law

In 1994, Oregon voters were the first in the nation to approve an act t…

-

![Ku Klux Klan]()

Ku Klux Klan

Fiery crosses and marchers in Ku Klux Klan (KKK) regalia were common si…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Ramos v Louisiana, 18-5924, S. Ct. (April 20, 2020). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/19pdf/18-5924_n6io.pdf

OR. CONST. art I, § 11.

One Juror Against Eleven, THE MORNING OREGONIAN, Nov. 25, 1933.

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968).

Apodaca v. Oregon, 406 U.S. 404 (1972).

Johnson v. Louisiana, 406 U.S. 356 (1972).