The Oregon and California Lands Act, heralded as a forward-looking conservation measure when it became law in 1937, has been mired in controversy for most of its existence. The origins of the O&C lands are rooted in the Pacific Railway Act of 1862 and its successors, measures that empowered Congress to provide subsidies in land and low-cost loans for railroad construction across the American West. In 1866, Congress bequeathed 3.7 million acres from the public domain to build a railroad from Portland to the California border. Empowered by Congress, the Oregon legislature selected Benjamin Holladay’s Oregon and California Railroad Company to build the line under specific federal stipulations, including a restriction to sell land only to “actual settlers” in 160-acre tracts.

O&C construction crews built the line through the Willamette Valley into the Umpqua watershed, reaching Roseburg in the fall of 1872. Caught in the financial panic of 1873 and heavily in debt, the company defaulted to German bondholders and their agent Henry Villard. The new owners were unable to raise capital to continue construction until 1881, when the O&C resumed its work, extending the line to Grants Pass and then to the new railway town of Medford. At that point, the overextended Villard lost control of the O&C, which became part of the Southern Pacific system. Southern Pacific finished construction into California in 1887, linking the Oregon section with its own railroad to Sacramento and beyond.

Trickery and subterfuge characterized virtually all railroad land grants in the American West. In the case of the O&C, the railroad delayed selecting its lands until toward the end of the nineteenth century, when timber speculators arrived in the Northwest to purchase large acreages of the region’s rich forestland. The Southern Pacific subsequently sold huge blocks of O&C timber to investors. The fraud involved in these transactions and others like them led to the Oregon land fraud trials, which took place between 1904 and 1908, and the conviction of U.S. Senator John Mitchell and Congressman John Willamson.

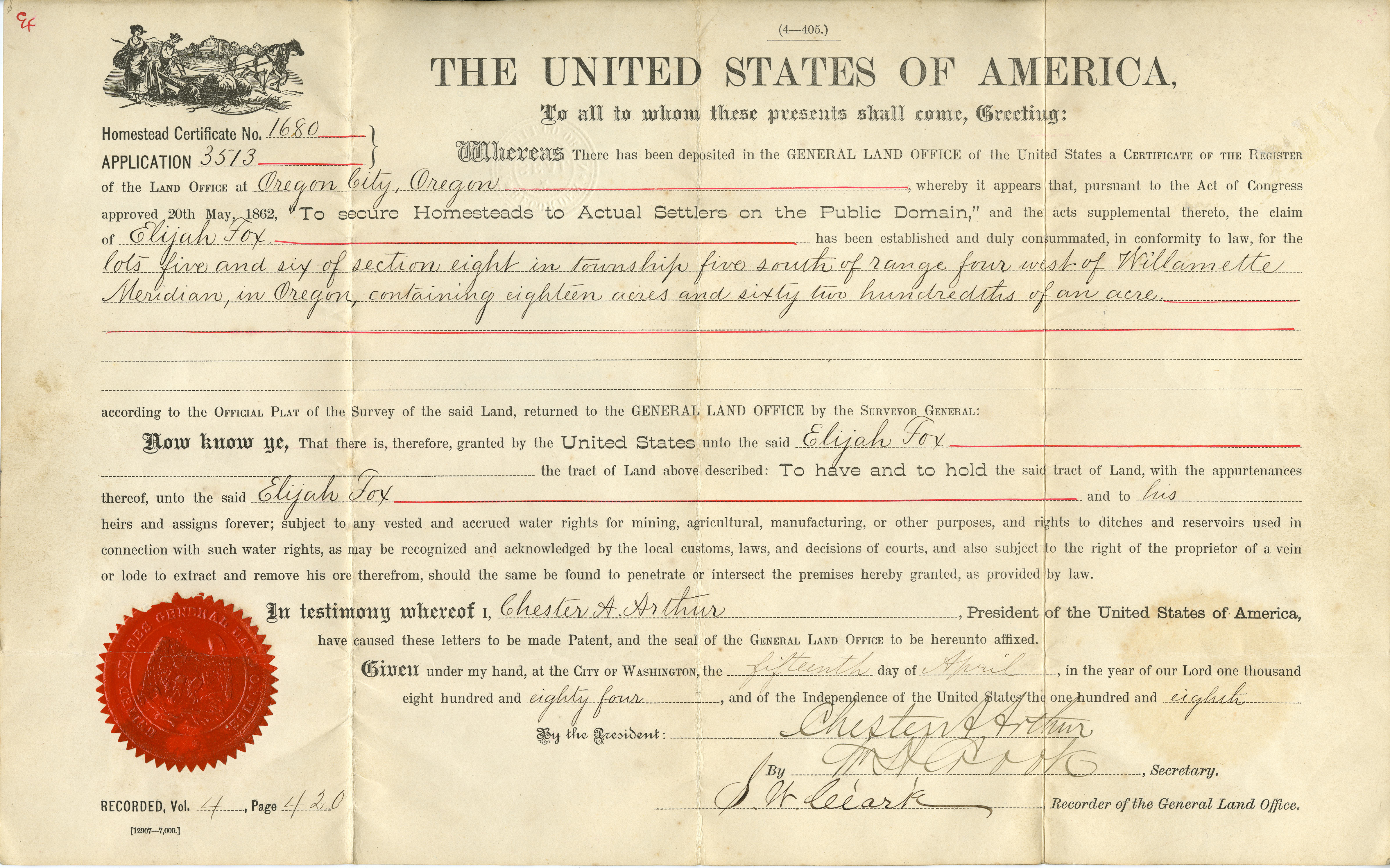

With federal support, Oregon brought suit against Southern Pacific for violating the “actual settler” clause in the original act when it sold land far in excess of the 160-acre limitation. The suit worked its way through the legal system to the Supreme Court, which found for the complainants in 1913 and directed the return of the unsold O&C lands to the government. Congress passed the Ferris-Chamberlin Act in 1916, which placed O&C lands under the jurisdiction of the General Land Office in the Department of the Interior.

The O&C lands remained in limbo until the Great Depression, when western Oregon’s financially strapped timber counties lobbied Congress to provide them with a dependable source of revenue. The result—the Oregon and California Sustained Yield Act of 1937—promised “a permanent source of timber supply, protecting watersheds, regulating stream flow, and contributing to the economic stability of local communities and industries, and providing recreational facilities.”

This paean to community stability and welfare worked well in the years of heavy timber harvesting following World War II. The new Bureau of Land Management, successor to the General Land Office, designated 50 percent of harvest revenue to O&C counties to fund their governments, thereby keeping taxes low. In addition, the counties received 25 percent of the receipts to apply to increasing timber harvests, campgrounds, and other timber-related enhancements. For two decades, jobs in the woods and mills were plentiful, and Oregon’s timber-dependent counties prospered.

Residual problems were accumulating, however. The rapid pace of road-building and harvesting and the size of some clearcuts contributed to landslides, erosion, and worsening water quality. By the mid-1950s, some sawmills were beginning to scramble for access to timber, and the BLM lifted marketing restrictions on timber sales. To stabilize employment, the agency established “marketing circles,” which required that timber harvested within a designated area had to be processed nearby. The larger issue, however, was the dwindling supply of timber available to mills, especially in southwestern Oregon, where there were huge acreages of O&C land. Diminishing timber supplies prompted both the BLM and the Forest Service to begin restricting harvests.

Beginning in 1979 and continuing to the mid-1980s, Oregon experienced one of the worst recessions in post-World War II history with mill closures and high unemployment in every timber district. A few mills, many of them retooled with automated equipment, reopened in O&C counties; but the sands were running out on the freewheeling policies of the past.

Declining salmon runs and diminishing numbers of northern spotted owls and other species led to Endangered Species Act restrictions on timber harvests, when federal district judge William Dwyer blocked timber sales on federal lands in 1991. This had the effect of shutting off supplies to mills relying heavily on federal timber, which led to a protracted conflict and brought hardship to rural counties that relied heavily on timber sales to support schools and other public services. As a result, the federal government has had to bail out cash-strapped O&C and other timber counties, an issue that was hotly contested.

With the creation of the Northwest Forest Plan in 1994, which included protection for the northern spotted owl, the U.S. Forest Service and the BLM were charged with developing management strategies to conduct experimental silvicultural studies and provide modest timber sales for local mills. For the most part, the plan fell victim to threats of environmental lawsuits opposing harvests of any timber. Although there have been modest thinning harvests, they have contributed little to the troubled economies in southwestern Oregon.

-

![Rev. Parrish drives the first spike for the Oregon Central Railroad, at E. Washington and 1st Ave., Portland.]()

Driving of first spike, Portland, 1869.

Rev. Parrish drives the first spike for the Oregon Central Railroad, at E. Washington and 1st Ave., Portland. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi6884

-

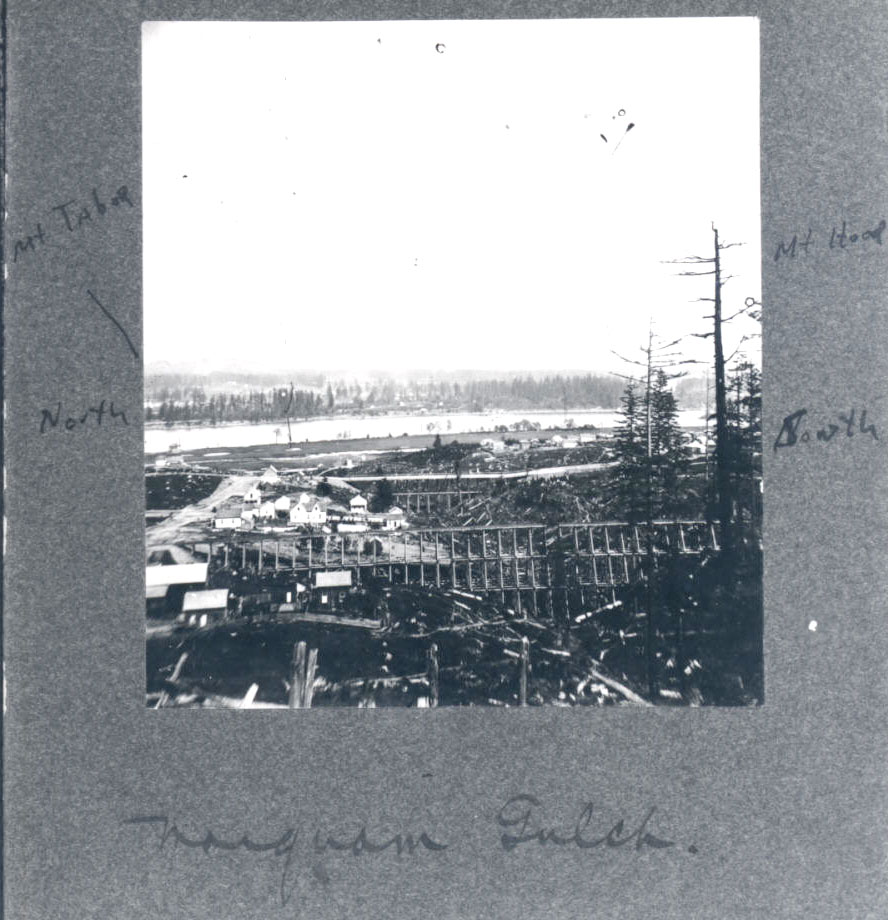

![O&C trestle across Marquam Gulch at 4th St. in Portland.]()

Trestle across Marquam Gulch, 1872.

O&C trestle across Marquam Gulch at 4th St. in Portland. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 002868

-

![]()

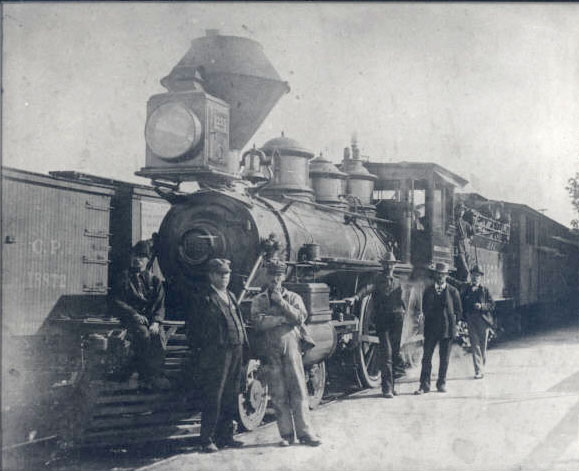

O&C engine, with crew.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 003238

-

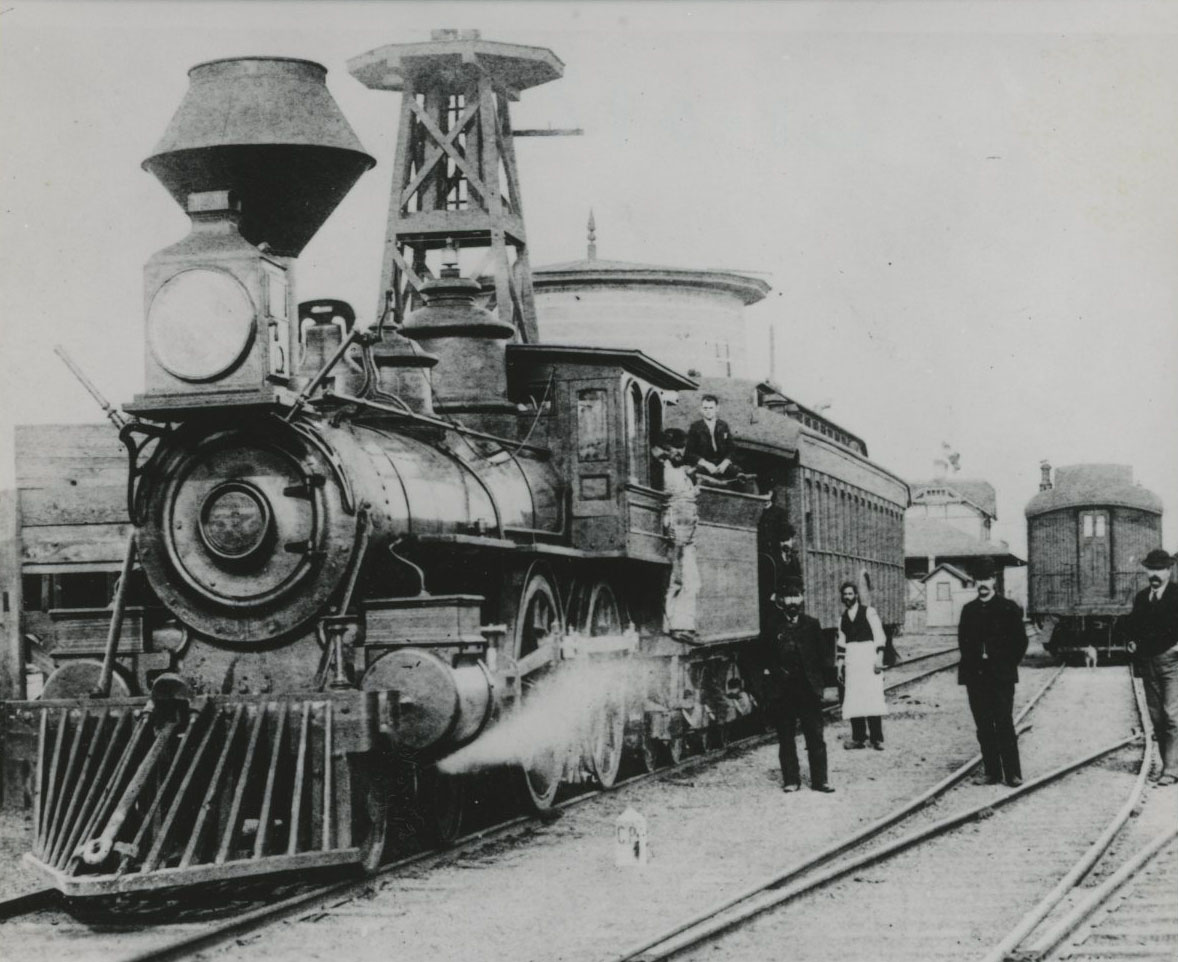

![]()

Oregon, California & Eastern Railroad, Klamath County, 1919.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 017872

-

![]()

Engine 1255, O&C.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 0356P129

-

![The title page to the U.S. Land Office regulations guidebook for opening O&C lands.]()

Regulations for opening former O&C lands, 1918.

The title page to the U.S. Land Office regulations guidebook for opening O&C lands. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

-

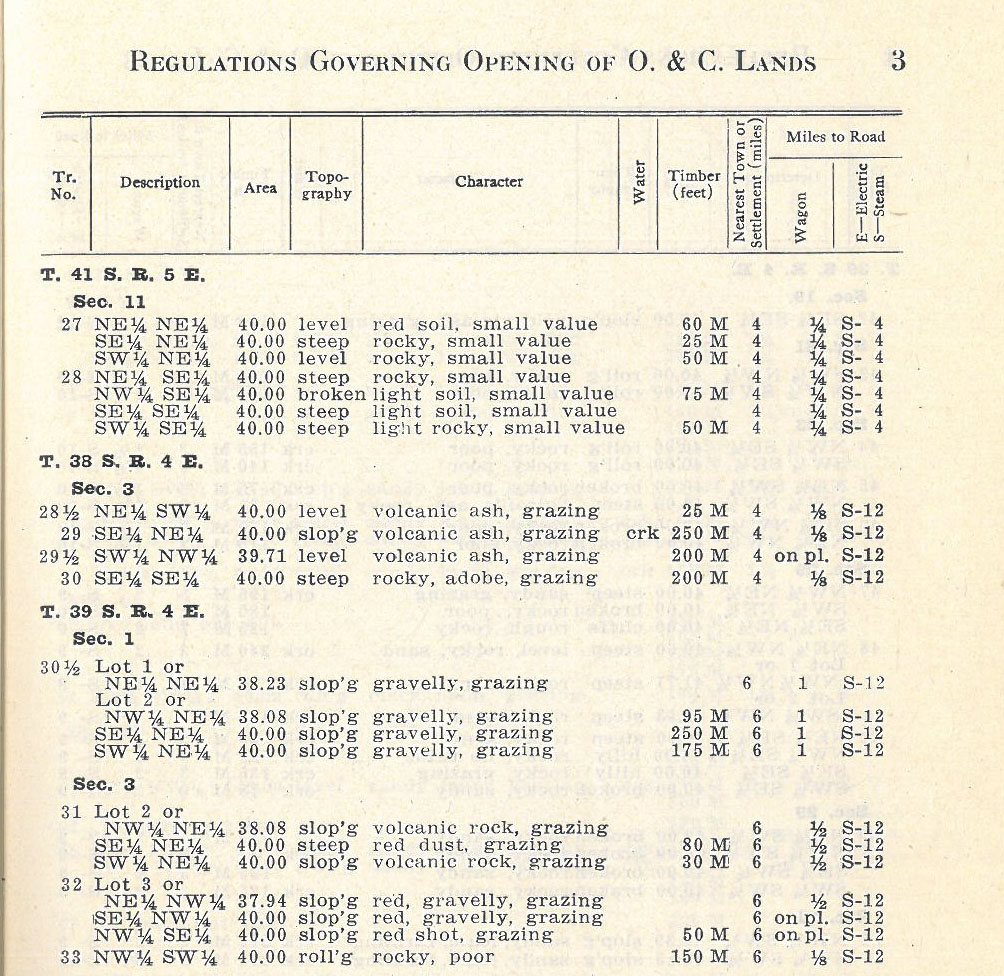

![Detail of land survey from the Regulations guidebook.]()

Regulations for opening former O&C lands, 1918.

Detail of land survey from the Regulations guidebook. Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library

Related Entries

-

![Henry Villard (1835-1900)]()

Henry Villard (1835-1900)

Henry Villard gained national significance as a journalist, advocate of…

-

![John Hipple Mitchell (1835-1905)]()

John Hipple Mitchell (1835-1905)

John Hipple Mitchell was a Portland lawyer and politician whose long ca…

-

![Oregon Land Fraud Trials (1904-1910)]()

Oregon Land Fraud Trials (1904-1910)

During the summer of 1905, while visitors enjoyed the amusements of the…

-

![Timber Industry]()

Timber Industry

Since the 1880s, long before the mythical Paul Bunyan roamed the Northw…

-

![U.S. Bureau of Land Management]()

U.S. Bureau of Land Management

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) administers over 15.7 million acres…

-

![U.S. General Land Office in Oregon, ca. 1850-1946]()

U.S. General Land Office in Oregon, ca. 1850-1946

With the acquisition of the Oregon Country in 1846, the United States w…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Ballaine, Wesley C. "The Revested Oregon and California Railroad Grant Lands: A Problem in Management." Land Economics 29.3 (1953): 219-232.

Robbins, William G. Landscapes of Conflict: The Oregon Story. Seattle: U of Wash. Press, 2010.

Oregon and California land grants: hearings before the Committee on Public Lands, House of Representatives, 64th Congress, 1st session, on H.J. Res. 58, H.J. 99814, and 10058. 1916.

Regulations governing opening to entry of former Oregon and California railroad grant lands under the provisions of the act of June 9, 1916 (39 Stat., 218) at the United States Land office, Roseburg.

Ben Holladay papers, 1862-1957. Mss 893. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Portland.

Richardson, Elmo. BLM's billion-dollar checkerboard: managing the O and C lands. Forest History Society, 1980.

O'Callaghan, Jerry A. The Disposition of the public domain in Oregon. New York: Arno Press, 1979.

Eastern Oregon Land Company records, 1884-1953. Mss 736. Oregon Historical Society Research Library, Portland.