Even before the first large wagon trains traveled the Oregon Trail to the Willamette Valley in the early 1840s, United States citizens who had resettled the region during the 1830s circulated petitions, requesting that Congress provide support for their fledgling communities. From 1818 until 1846, when the Oregon Treaty with Great Britain was ratified, the Oregon Country was open to citizens of both nations in joint-occupancy, with no prejudice toward nationals of either one. Nonetheless, American resettlers desired a legal connection to the nation, which would bring economic, political, and social benefits. Aside from electoral voting, the only effective means to achieve their goal and affect national policy-making was through a direct petition to the U.S. Congress. The petitions had to be introduced by a member of Congress, and petitioners from Oregon found willing U.S. senators in Thomas Hart Benton and Lewis Linn of Missouri, who were champions of western expansion.

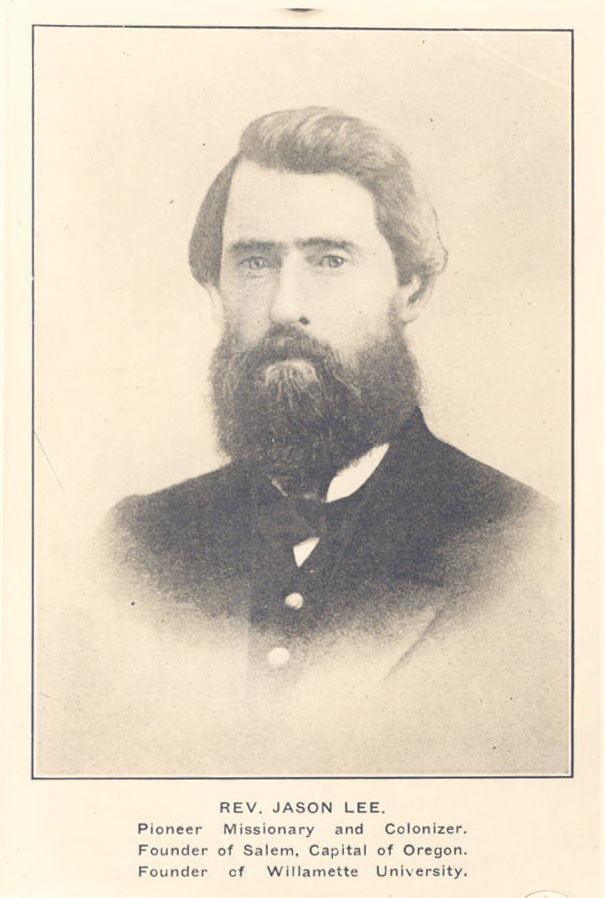

The first petition, crafted in 1838, originated in the Willamette Valley community created by Methodist missionaries during the early 1830s. The petition, written by Jason Lee and put into form by Philip L. Edwards, included a description of the social and economic labors of U.S. citizens in Oregon and clearly requested aid and political affiliation. The petition text concluded: “We have thus briefly shown that the security of our persons and our property, the hopes and destinies of our children, are involved in the objects of our petition. We do not presume to suggest the manner in which the country should be occupied by the Government, nor the extent to which our settlement should be encouraged. We confide in the wisdom of our national legislators, and leave the subject to their candid deliberations, and your petitioners will ever pray.”

The petition, presented to Congress by Lee and Edwards in January 1839, bore the signature of J.L. Whitcomb, a teacher at the Willamette Mission, plus thirty-five others, including nine French Canadians who professed to seek U.S. citizenship. In December 1839, U.S. Senator Lewis Linn, from Missouri, offered a resolution in the Senate that the U.S. government establish military protection for citizens in Oregon. In mid-April 1840, Linn and Kentucky Senator Henry Clay offered additional resolutions that proposed establishing military forts from the Rockies to Oregon and the institution of a land grant to resettlers. Proposing a military action proved too controversial, however, and Congress tabled the petition on April 28, 1840, without further action.

The second petition from resettlers in Oregon, often called the Farnham Petition, originated with members of an emigration party from Peoria, Illinois, who had arrived in the Willamette Valley in October 1839. Thomas Jefferson Farnham and eighteen compatriots had struck out for Oregon purposely to bring the area into the federal union, burnishing a travel banner “Oregon or the Grave.” His route took him first to Santa Fe and then to Oregon, an emigration that exposed Farnham as a trail despot and self-promoter, which prompted defections from his group that left only nine of his original party with him when they arrived in Oregon.

According to Farnham, in Travels in the Great Western Prairies (1843), Americans in the Willamette Valley who worried about British imperial intentions in Oregon pressed a petition on him asking for U.S. governmental aid. He sent the petition, which had more than sixty signatures, to Washington, D.C., by way of Hawaii. Senator Linn introduced it to the Senate on June 4, 1840, and had it printed for distribution. The petition called for American sovereignty in all of Oregon and was stridently anti-Hudson’s Bay Company and anti-British. It was likely the work of two Willamette Mission officials, David Leslie and Elijah White. On January 8, 1841, Senator Linn raised the petition again and advocated for government-authorized occupation of Oregon. It died in committee hearings.

The third petition originated with George Abernethy, acting in the interests of Methodists who had created a milling company at Willamette Falls and were engaged in a dispute over a land claim made by Hudson’s Bay Company Chief Factor John McLoughlin. The petition itemized supposed illegal actions by McLoughlin in perfecting his claim and generally appealed to the government for protection. “And now your memorialists pray your Honorable Body,” the petition concluded, “that immediate action of Congress be taken in regard to this country and good and wholesome laws be enacted for our Territory as may in your wisdom be thought best for the good of the American citizens residing here.”

Sixty-five signatures appeared on the petition, but Abernethy had abstained to protect his financial interests and pressed Robert Shortess to head up the appeal for government aid. Shortess was a native of Ohio and an original member of Farnham’s emigrant train. He had separated from Farnham and made it to Oregon on his own in 1839. Shortess circulated Abernethy's petition just months before the meeting at Champoeg in May 1843, where participants agreed to form a provisional government. Missouri Senator David Atchison, who had replaced Lewis Linn in the Senate, introduced the so-called Shortess Petition on February 7, 1844. The Senate debate on the petition languished and laid it to rest with no action taken on March 6, 1844.

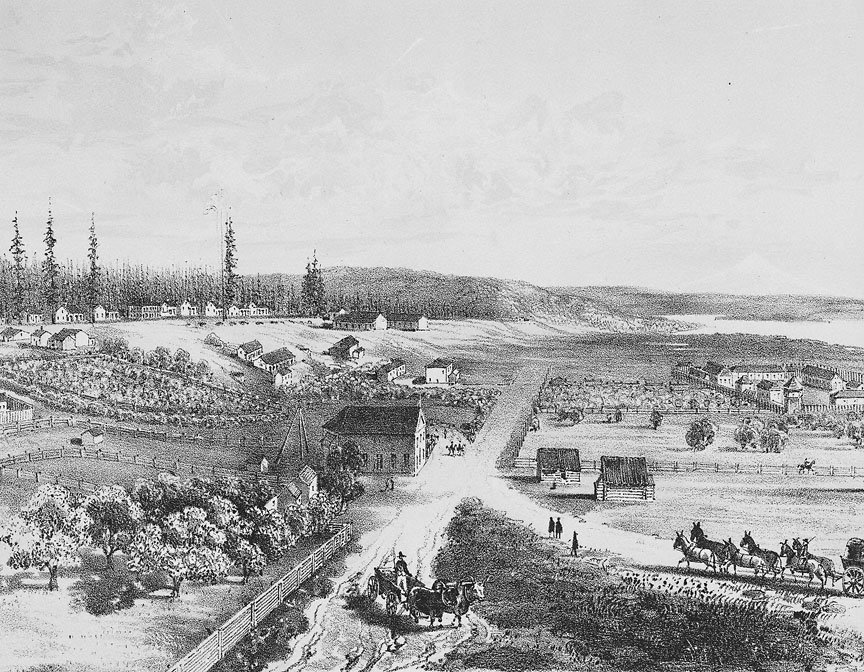

The last petition to Congress before the completion of the Oregon Treaty came from the Provisional Government’s Legislative Assembly in June 1845. A five-person committee drew up the petition, which was signed by a thirteen-member legislative committee, plus James Nesmith, judge of the Circuit Court, and Osborne Russell and Peter G. Stewart for the Provisional Government executive branch. The petition, submitted to Congress on December 8, 1845, was introduced by Senator Benton: “These petitioners stated that, for the preservation of order, they had, among themselves, established a provisional and temporary government, subject to the ratification of the United States government.” The petition advocated for territorial status for Oregon and congressional extension of “adequate military and naval protection, so as to place us at least upon a par with other occupants of this country.” It announced the formation of the Provisional Government and presaged the creation of Oregon Territory in 1848.

-

![]()

Rev. Jason Lee.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, OrHi634

-

![]()

Elijah White.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi728

-

![George Abernethy, Oregon's first and only provisional governor, 1845 to 1849.]()

George Abernethy.

George Abernethy, Oregon's first and only provisional governor, 1845 to 1849. Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., bb003864

-

![]()

James Nesmith.

Courtesy Library of Congress

Documents

Related Entries

-

![George Abernethy (1807-1877)]()

George Abernethy (1807-1877)

George Abernethy cut a wide swath through Oregon's religious, economic,…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

![Jason Lee (1803-1845)]()

Jason Lee (1803-1845)

Few names in the history of early nineteenth-century Oregon are better …

-

![John McLoughlin (1784-1857)]()

John McLoughlin (1784-1857)

One of the most powerful and polarizing people in Oregon history, John …

-

![Oregon Question]()

Oregon Question

“The Oregon boundary question,” historian Frederick Merk concluded, “wa…

-

![Willamette Mission]()

Willamette Mission

Willamette Mission was the first noncommercial agricultural community e…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Bancroft, Hubert Howe. The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft. Vol. 29: The History of Oregon, Vol. I. San Francisco, 1886.

Churchill, Charles B. “Thomas Jefferson Farnham: An Exponent of American Empire in Mexican California.” Pacific Historical Review (November 1991): 519-21.

Congressional Globe, 25th Cong., 3d sess. 141 (1839); 25th Cong., 1st sess. 296 (1840); 26th Cong., 1st sess. 440 (1840); 29th Cong., 1st sess. 24 (1845).

Duniway, David C., and Neil R. Riggs. “The Oregon Archives, 1841-1843.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (June 1959): 228-36.

Loewenberg, Robert J. Equality on the Oregon Frontier. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1976.

Pike, C.J. “Petitions of Oregon Settlers, 1838-48.” Oregon Historical Quarterly (September 1933): 216-35.