Located at the mouth of the Columbia River and marking the extreme northwestern corner of Oregon, Point Adams is a pivotal landmark in the geography and history of the state. For the Clatsop people, this was the site of the prominent village, Klaát-sop, for which their nation was named. The village was a fishing place of great importance, and Klaát-sop was a reference to the salmon that were caught, processed, and traded from this location. With its position at a regional crossroads, the village was among the great trading centers of the lower Columbia region.

Once European and American ships began plying the Northwest coast, the mouth of the Columbia River became internationally famous for its perilous crossings of the bar and the high number of shipwrecks that occurred there. Upward of two thousand ships have been lost in or near the mouth of the Columbia, prompting the development of both a Point Adams lighthouse (since demolished) and a lightship service during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Fronting both the open ocean and the relatively placid waters of the Columbia River estuary, the Point Adams landscape consists of rolling sand dunes transected by streams, lakes, and estuarine side channels in the low places between. Well-established dunes are clad in Sitka spruce forest with a dense understory of evergreen huckleberry, salal, and other salt-tolerant shrubs; younger dunes have shrubby forests of both native and non-native pines and beach-grass fields, many planted to stabilize the shifting dunes. A rich cultural landscape of military forts, Native sites, shipwrecks, jetties, and other built features overlays the dynamic and windbeaten environment.

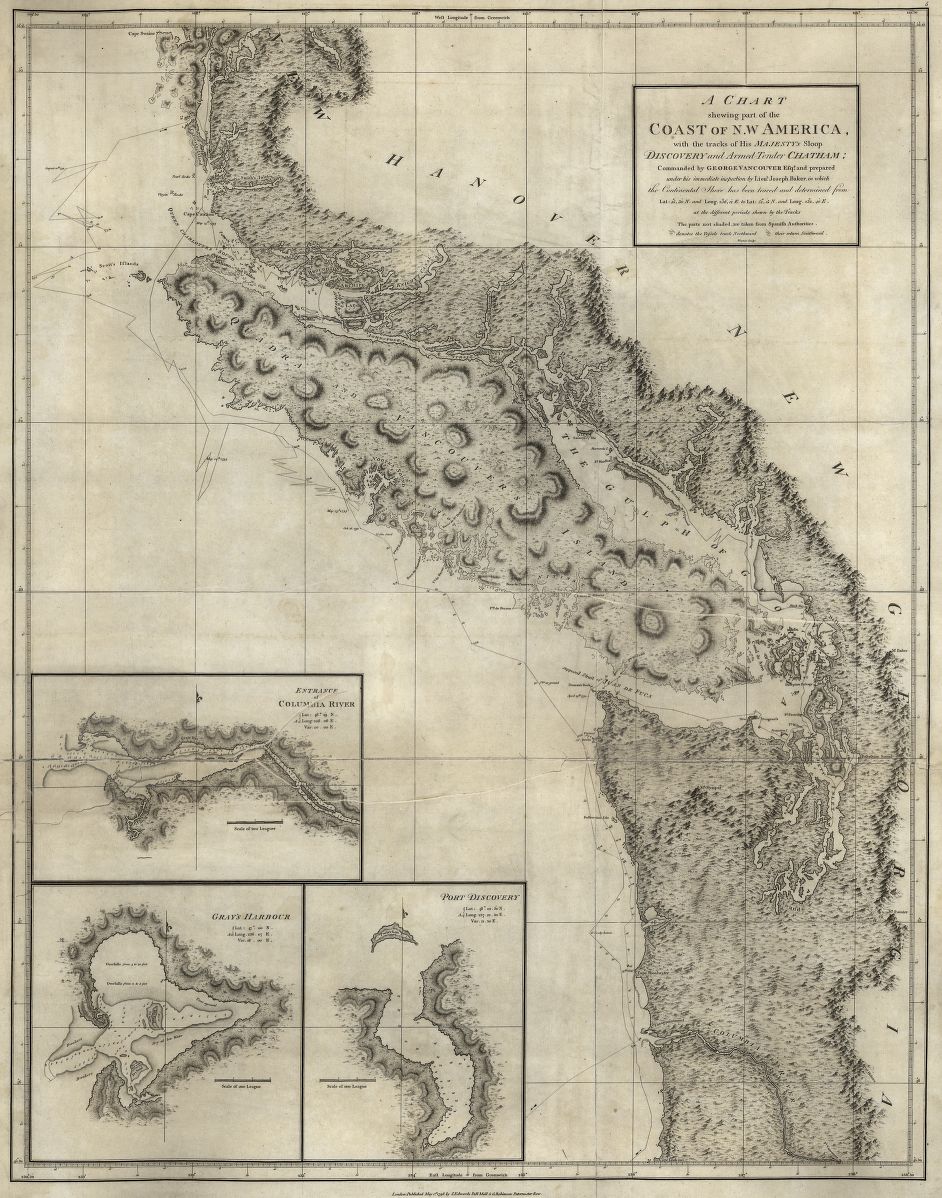

Spanish explorer Bruno de Hezeta y Dudagoitia may have been the first non-Native explorer to document Point Adams. Sailing on the present-day Oregon coast in 1775, he recognized that the Columbia estuary represented a broad “bay” but he could not enter it safely. Hezeta recorded a landmark, perhaps Point Adams, as Cabo Frondoso (“Verdant Cape”). On May 19, 1792, Captain Robert Gray described Point Adams in his official log and named it after President John Adams. Captain George Vancouver documented the same landmark later that year, referring to it as Point Adams, and the U.S. Exploring Expedition officially retained that name beginning in 1841.

The village at Point Adams was a center of tribal life and trade during the fur trade period, despite many incursions by non-Natives. In 1829, the Hudson’s Bay Company bombarded the village in response to false rumors of Clatsop attacks on survivors of the William & Ann shipwreck, and white settlers began encroaching on the site. During the 1851 Tansy Point treaty negotiations to extinguish title of Columbia-Pacific tribes, U.S. negotiators promised Point Adams to the Clatsop as a small reservation. Congress did not ratify these treaties, in part because Oregon Territorial Delegate Joseph Lane and others opposed placing a reservation in an area they believed had strategic value.

The military potential of Point Adams was appreciated by Henry Warre and Mervin Vavasour, British spies who in 1845-1846 proposed a military installation at the site in anticipation of a territorial war with the Americans. In 1852, within six months of the Tansy Point treaty, President Millard Fillmore authorized the construction of a military installation on Point Adams to defend American interests in the thinly settled territory. The construction of the earthwork Fort Stevens in 1863 prompted the forcible removal of the Clatsops from their ancestral village, some to the Coast Reservation; others became part of nonreservation Native communities in northwestern Oregon and southwest Washington.

The army used Fort Stevens when the Pacific became a theater of American military operations during the Spanish-American War, the Philippine revolutionary wars, and the Philippine–American War from 1896 to 1902. After the end of hostilities, the fort languished and was threatened by coastal erosion, which by the 1880s galvanized Congress to fund the Columbia River South Jetty.

Responding to both the navigational hazards of the Columbia bar and erosion that jeopardized the fort, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began constructing South Jetty at Point Adams in 1885, completing it in 1895. The Corps built an extension of the jetty in 1913 that reached 3,300 feet out to sea. By the early twentieth century, North and South Jetties together constituted the largest jetties on earth. South Jetty was strengthened in 1931-1936, but sea action continuously raveled the end, necessitating the placement of a concrete terminal that lengthened the jetty to 3,900 feet. The most recent repairs to South Jetty were completed in 2007.

Because of the jetties, Point Adams has progressed toward the sea, extended by sand accumulation at Clatsop Spit. Natural vegetation stabilized the sand with remarkable speed, succession proceeding in some places from dune grasses to shrubs and shore pine to deep Sitka spruce forest in just over a century’s time. Narrow lakes and lateral streams have formed behind rapidly advancing dune ridges, producing habitat for birds and other species. Civilian Conservation Corps planting of largely nonnative plants in the 1930s also contributed to the rapid change.

Fort Stevens last served as a military installation during World War II. Samuel H. Boardman, Oregon State Parks superintendent, began working to acquire Point Adams federal lands for Fort Stevens State Park as early as 1946. The State Highway Commission, concerned about maintenance and unsure of the area’s value as a park, rejected Boardman’s proposal twice. Negotiations continued after Boardman’s death in 1953, and the park became a reality in 1955, with strong civic support and donations by the City of Hammond, Clatsop County, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and a private donor. The Corps of Engineers retained its ownership of land around South Jetty, and there is a patchwork of private and public land. Over 1,200 acres is still owned by the United States as surplus military property and is leased to the State of Oregon for park use. Point Adams, enlarged by Clatsop Spit, is now a low sandy promontory and a central part of Fort Stevens State Park.

-

![]()

Chart of the lower Columbia River, c.1836.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Salcum, 917.91S1837, paowcez

-

![]()

View of the jetty near Fort Stevens.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 27906

-

![]()

Locomotive carrying boulders to the South (?) Jetty, c.1931.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Oregon Journal, 371N5713

-

![]()

Crane pushing boulders on the South (?) Jetty, c.1931.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Oregon Journal, 371N5715

-

![]()

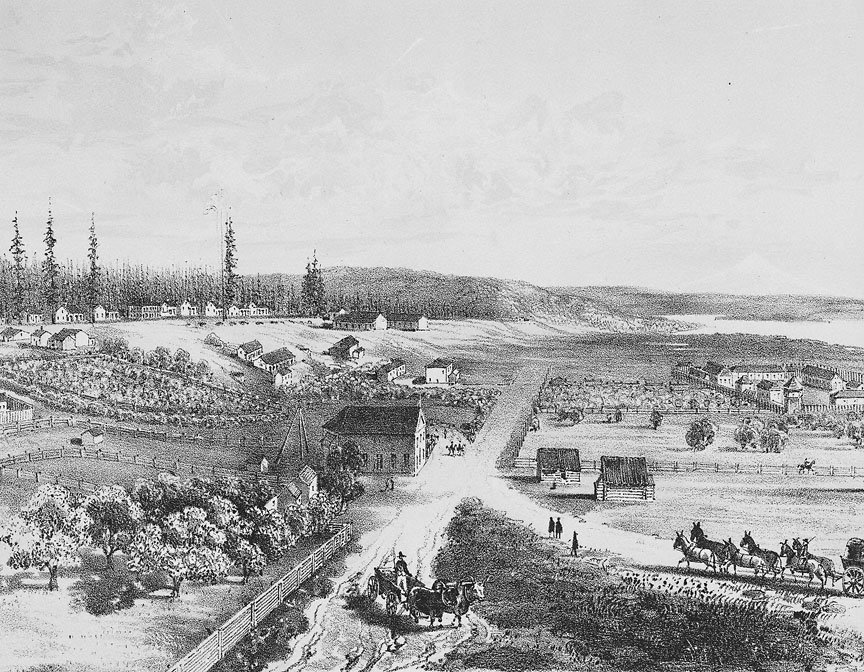

Long view of Fort Stevens, near Hammond, 1938.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 52546

-

![USLSS Station Point Adams, about 1910.]()

USLSS Sta Point Adams, ca 1910.

USLSS Station Point Adams, about 1910. Courtesy USCG HQ -

![]()

"Old Point Adams Lighthouse".

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Orhi76254, pf654c

Related Entries

-

![Bruno de Hezeta y Dudagoitia (1744-1807)]()

Bruno de Hezeta y Dudagoitia (1744-1807)

Bruno de Hezeta y Dudagoitia, a Spanish naval officer, commanded an exp…

-

![Columbia River]()

Columbia River

The River For more than ten millennia, the Columbia River has been the…

-

![Fort Stevens]()

Fort Stevens

One of the three major forts designed to protect the mouth of the Colum…

-

![George Vancouver (1757-1798)]()

George Vancouver (1757-1798)

The role George Vancouver played in Oregon history is tangential, yet i…

-

![Hobsonville Indian Community]()

Hobsonville Indian Community

The Hobsonville Indian Community was a Native settlement on Tillamook B…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

![Konapee wreck]()

Konapee wreck

The possible wreck of a European ship at Point Adams, on the southern e…

-

![Point Adams Lighthouse and Life-Saving Station]()

Point Adams Lighthouse and Life-Saving Station

Point Adams was given its name by Captain Robert Gray, who in his offic…

-

![Robert Gray (1755–1806)]()

Robert Gray (1755–1806)

On May 11, 1792, Robert Gray, the first American to circumnavigate the …

-

![Shipwrecks in Oregon]()

Shipwrecks in Oregon

Approximately three thousand ships have met their fate in Oregon waters…

-

![U.S. Life-Saving Service in Oregon]()

U.S. Life-Saving Service in Oregon

The mission of the U.S. Life-Saving Service was to rescue those in peri…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Deur, Douglas. Empires of the Turning Tide. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Publication Number 2016-001. 2016.

Deur, Douglas. “The Making of Seaside’s Indian Place: Contested and Enduring Native Spaces on the Nineteenth Century Oregon Coast.” Oregon Historical Quarterly 117.4 (2016).

Hanft, Marshall. Fort Stevens: Oregon's defender at the river of the West. Salem: Your Town Press, 1980.