Robert Shortess, an early pioneer in Oregon, played a significant role in the acquisition of Oregon Territory, the formation of the Oregon state government, and in the region’s relationship with Native tribes. He was at times a key player in the formation and administration of Oregon’s early government, served as a subagent, and held other official positions.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1797, Shortess grew up in Ohio. In the 1830s, while living in Missouri, he met Lindsay Applegate, who hired him as a miller and surveyor. When the Applegates’ gristmill was flooded out in 1839, he joined the Peoria Party, a group of men from Illinois led by Thomas J. Farnham headed to the Oregon Country. Shortess separated from the group at Bent’s Fort in Colorado and led seven people from the original group to Fort Crockett in Wyoming before traveling to Fort Hall in Idaho. The final leg of the journey into Oregon ended in the Willamette Valley in April 1840.

Shortess joined the Methodist Mission Church in present-day Salem in 1841. In letters, he described the Willamette Valley’s mild climate and green hills to Lindsay Applegate, which persuaded the Applegate family and their neighbor Daniel Waldo to emigrate to Oregon in 1844.

In 1843, politician and businessman George Abernethy recruited Shortess to lead an appeal to Congress for government aid to Oregon. Sixty-five people signed what became known as the Shortess Petition (also known as the Farnham Petition), which helped prompt a debate in Congress about the fate of the Oregon Country. On March 2, 1843, Shortess was appointed to the Oregon Provisional Legislature at Champoeg. He became a member of the Committee of Twelve at the Second Wolf Meeting on March 6, and on May 16 he was appointed to a three-person committee to prepare the rules and business for the House, where he served on the Ways and Means and the Private Land Claims committees.

The next year, Shortess took up a land claim in Astoria, at Alderbrook, just south of Tongue’s Point. He worked as a farmer and married a Clatsop woman called Ann; they had a child named Susan. Shortess claimed that he owned two miles along the shoreline because of a hereditary title he received from his wife’s family, although such Indian claims had no legal standing under U.S. law at the time. He was appointed to a two-year term as Clatsop County district judge in August 1845.

Anson Dart, the Oregon superintendent of Indian Affairs, named Shortess subagent of the Astoria District in October 1850, tasking him with arresting Indians for crimes against Americans and keeping them from liquor. Shortess felt a personal need to enforce prohibition among the tribes, both because of the Methodist Church’s position on liquor and because some settlers were using liquor to steal land from Native people, many of whom were Shortess’s relatives.

In February 1851, Shortess reported a census of the Lower Columbia tribes and prepared the Chinook and Tillamook tribes for treaty negotiations. He served as a translator during the negotiations with several tribes at Tansy Point, likely communicating in Chinuk Wawa (Chinook Jargon). Shortly after, he wrote Dart, siding with the tribes over Washington Hall, who had claimed the land, and requesting that Hall vacate the claim. On October 10, 1851, Dart wrote Hall that he did not need to vacate the claim and that Shortess would no longer be an Indian agent. He then fired Shortess by a letter on October 18, 1851.

A friend of ethnographer George Gibbs, Shortess collected a vocabulary of Lower Chinookan and Chinook Jargon, which is now part of the National Anthropological Archives Collections of the Smithsonian Institution. He likely collected the vocabularies through interactions with his Clatsop family.

In 1854, Shortess was on the Gazelle sidewheeler when it exploded at the wharf at Canemah at Willamette Falls, killing twenty people outright and four people later from mortal injuries. He escaped with minor injuries. A few years later, on December 7, 1857, Shortess held a yearlong term as sergeant-at-arms for the Ninth Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Oregon. He was named superintendent of Public Schools for Clatsop County in 1864.

Shortess spent the rest of his life as a farmer and education administrator in Astoria, before selling all but three acres of his land claim in 1870 and moving to John Day, near Astoria, to live with his daughter. He died on May 4, 1878, and is buried in the Astoria Pioneer Cemetery.

-

![]()

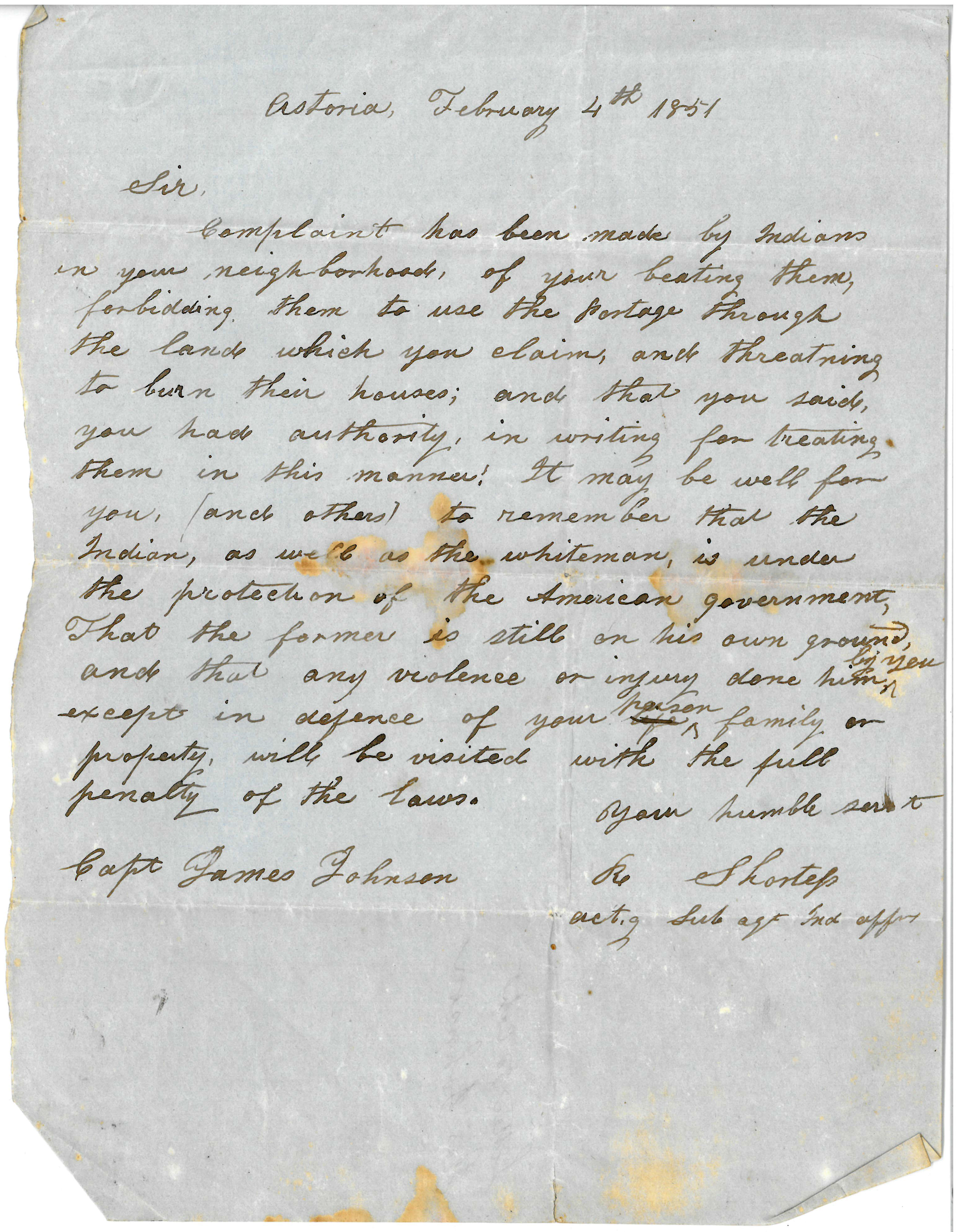

Letter from Shortess to Capt. James Johnson, warning him to stop abusing Native Americans, 1851.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., Coll., Mss1189

Documents

Related Entries

-

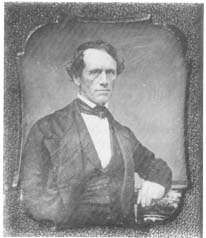

![Anson Dart (1797-1879)]()

Anson Dart (1797-1879)

In 1850, Anson Dart (1797-1879), of Wisconsin, was appointed as the fir…

-

![Champoeg]()

Champoeg

The town of Champoeg had a brief but memorable life. Instigated by geog…

-

![Chinook Jargon (Chinuk Wawa)]()

Chinook Jargon (Chinuk Wawa)

According to our best information, the name "Chinook" (pronounced with …

-

![Gazelle Disaster]()

Gazelle Disaster

The worst steamboat accident on the Willamette River happened on April …

-

Jesse Applegate (1811-1888)

Jesse Applegate, an influential early Oregon settler, is most remembere…

-

![Petitions to Congress, 1838-1845]()

Petitions to Congress, 1838-1845

Even before the first large wagon trains traveled the Oregon Trail to t…

-

![Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the early 1800s]()

Portland Basin Chinookan Villages in the early 1800s

During the early nineteenth century, upwards of thirty Native American …

-

![Provisional Government]()

Provisional Government

The Provisional Government, created in May-July 1843, was the first gov…

-

![Willamette Mission]()

Willamette Mission

Willamette Mission was the first noncommercial agricultural community e…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Couture, Ann Hoffman. "Robert Shortess." In Astorians Eccentric and Extraordinary, by Calvin Trillin. Pendleton: East Oregonian Publishing Co., 2010.

Dobbs, Caroline C. Men of Champoeg. Cottage Grove, Ore.: Emerald valley Craftsmen, 1975

Howison, Neil M. "Report of Lieutenant Neil M. Howison on Oregon, 1846: A Reprint." Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 14 (March 1913): 1-60.

Journal of the Proceedings of the Council of the Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Oregon, 1857.

Shortess, Robert. "First Emigrants to Oregon." In Transactions of the Oregon Trail Association, 1896.

The Oregon Archives: Including the Journals, Governors' Messages and Public Papers of Oregon, from the Earliest Attempt on the Part of the People to Form a Government, Down To, and Inclusive of the Session of the Territorial Legislature : Held in the Year 1849 : Collected and Published Pursuant to an Act of the Legislative Assembly, Passed Jan. 26, 1853