Jedediah Strong Smith was one of the first and, arguably, the most important of the American trappers and explorers who penetrated the interior Oregon Country in the 1820s. Prior to his arrival in 1826, almost no American trappers had scoured Oregon, and none produced maps to rival the significance of Smith’s master map, which he drafted during his years in the West. Smith and his men bid defiance to the entrenched Hudson’s Bay Company, but also began to tilt the balance of sovereign power toward the United States in the emerging Oregon Question, which was not settled until 1846. Smith’s reports, maps, letters, and journals played a large role in boosting U.S. interest in the Oregon Country, for he was well connected with politicians and entrepreneurs who believed the United States must secure Oregon. Information culled from Smith’s maps also appeared on several maps of the Far West printed between 1836 and 1841.

While in present-day Oregon, Smith’s outfit encountered stout competition from the Snake River Brigades of the Hudson’s Bay Company (1822-1830), led by Peter Skene Ogden, Smith’s opposite number in the Oregon beaver trade. By turns shadowing, harassing, and sharing camps with Ogden’s outfit, Smith learned much about the Oregon Country and its Native residents. Like other fur men, his dealings with Indigenous people ranged from friendship to outright murder, though in general he attempted to maintain peace with Indians by offering gifts and developing trade.

In 1822, Jedediah Smith, a twenty-three-year old New Yorker, arrived in St. Louis, Missouri, where he found employment as a hunter with William H. Ashley and Andrew Henry’s fur-trading company. He accompanied Ashley and Henry’s fur-trapping brigade bound for the Rocky Mountains and spent the next decade as a mountain man, gaining renown as an explorer and talented cartographer. His travels from 1823 to 1828 took him from the South Pass in Wyoming to the Oregon Country, and twice to Mexican California before he again returned to Oregon. In letters to Ashley and others in St. Louis, Smith described the South Pass and thus played a critical role in the inception of what later became known as the Oregon Trail. By 1826, he and two partners (David Jackson and William Sublette) bought out Ashley and Henry. The new firm, Smith, Jackson & Sublette, operated until 1830.

Smith spent the better part of four years in the Oregon Country and made two excursions of significance to Oregon history during 1826-1828. In 1826, he led a small trappers’ brigade across the Mojave Desert into Mexican California. Suspicious Mexican officials detained the Americans for a time and then ordered them to return to the United States by the same route. Instead, Smith led his men north, bushwhacking through the great coastal forests to the California-Oregon borderlands. In May 1827, Smith established a camp near the Stanislaus River, in the vicinity of present-day Modesto. While the bulk of his men remained to trap and hunt, Smith with two other men departed in May for the 1827 fur trade rendezvous near Bear Lake in present-day Idaho, where he was to re-supply and prepare to return to the Stanislaus. They arrived in early July, having completed the first documented transit of the Great Basin and the first eastward crossing of the Sierra Nevada.

On July 13, 1827, Smith departed the rendezvous with another brigade to collect the men he had left in northern California in May. He suffered a devastating encounter in mid-August with angry Mohaves at the Mojave Crossing of the Colorado River, near today’s Laughlin, Nevada, where half of his men were killed. Staggering destitute into California, Smith and his men were again detained. When Smith left California in January 1828, he once more determined to go his own way and returned to the Stanislaus River camp. There he gathered the trappers he had left behind in 1827 and set off on a Northwest Expedition toward the Columbia River, the first documented overland trek from San Francisco to the Columbia.

Smith’s 1828 trek from northern California to Oregon, however, had been fraught with violence between his men and Natives. Escalating mistrust and violence precipitated the Umpqua Massacre on July 14, 1828, when aggrieved Lower Umpqua (Kalawatset) tribesmen murdered all but four trappers in a dawn attack on the debilitated brigade. Smith with two survivors (and separately, a trapper named Arthur Black) made their way to the Hudson Bay Company’s Fort Vancouver, where Chief Factor John McLoughlin sheltered them. McLoughlin dispatched a party under the command of Alexander R. McLeod with orders to restore peace with the Indians, avoid bloodshed, and retrieve as much as possible of Smith’s stolen furs and gear. After wintering at the trading post, Smith sold his furs and livestock to the Hudson’s Bay men, then returned to the central Rockies and eventually to St. Louis. In 1831, Smith disappeared on the Santa Fe Trail in present-day Kansas. His companions recovered his belongings, but Smith was never found.

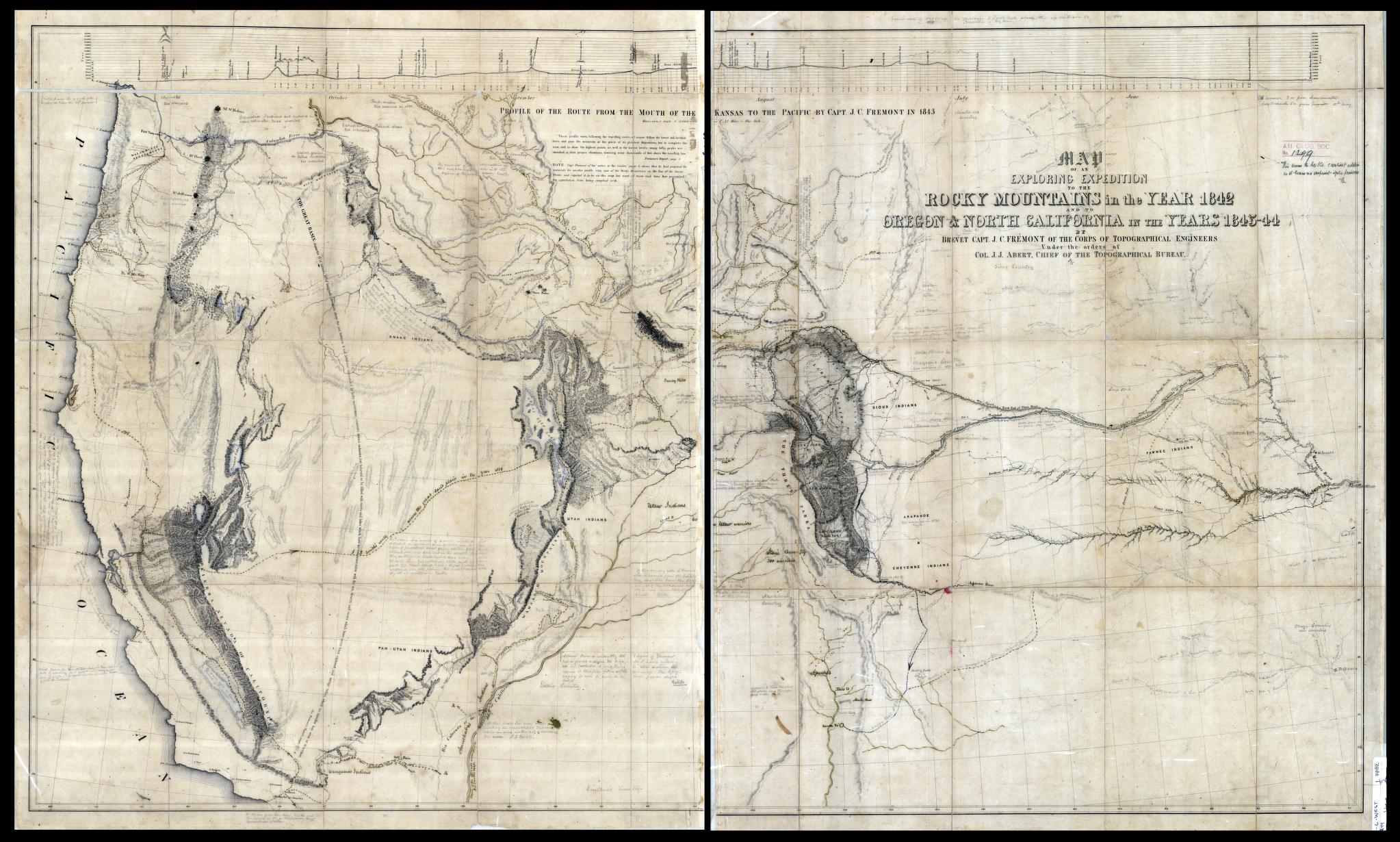

While at Fort Vancouver, Smith presented John McLoughlin with a copy of his master map of the West. None of Smith’s original maps are extant, but definitive evidence of his remarkable cartographic achievements appears on a map discovered by historian Dale L. Morgan and cartographer Carl I. Wheat in 1953, and published a year later. About a hundred years earlier, in 1850, likely at Fort Vancouver, surveyor George Gibbs had studied Smith’s map and transferred dozens of detailed notations onto a printed copy of John C. Frémont’s 1845 map of the West. Encompassing territory from the South Pass to the Mojave Desert and from Monterrey, California, to the Columbia River, details from Smith’s map had by 1850 already been utilized in maps drafted by Albert Gallatin (1836), David H. Burr (1839), and U.S. Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes (1841). A number of Smith’s place-names still appear on modern maps.

Jedediah Smith played a singular role in developing significant information about Oregon and the Natives who lived there. His reports spurred the growth of the Far Western fur trade, influenced expansionist views of politicians such as Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, and greatly boosted the United States’ interest in securing the Oregon Country. Smith’s identification of the South Pass as a key feature in the future “high-way” to Oregon and the Far West made feasible the rising tide of American emigrants that followed the Oregon Trail to the Willamette Valley after 1840 and tilted the balance of power in favor of the United States, thus enabling the permanent settlement of the Oregon Question in 1846.

Two Pacific Coast rivers bear Smith’s name, one in northern California north of Crescent City and one in Oregon, a tributary of the Umpqua River that joins the Umpqua at Reedsport, where the Umpqua Massacre took place.

-

![]()

Jedediah Smith.

Courtesy Fine Arts Press, public domain

-

![The geographical knowledge of the mountain man Jedediah Smith (1799--1831) is recorded by George Gibbs on this map.]()

Map of an Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1842, Oregon and North California in the Years 1843-44.

The geographical knowledge of the mountain man Jedediah Smith (1799--1831) is recorded by George Gibbs on this map. Courtesy Library of Congress, Frémont, J. C., Gales And Seaton Printer, Gibbs, G., Smith, J. S. & United States Army. Corps Of Topographical Engineers Sponsor. (1844)

Related Entries

-

![Fur Trade in Oregon Country]()

Fur Trade in Oregon Country

The fur trade was the earliest and longest-enduring economic enterprise…

-

![Oregon Trail]()

Oregon Trail

Introduction In popular culture, the Oregon Trail is perhaps the most …

-

![Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)]()

Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)

More than any other figure during the years of the Pacific Northwest's …

-

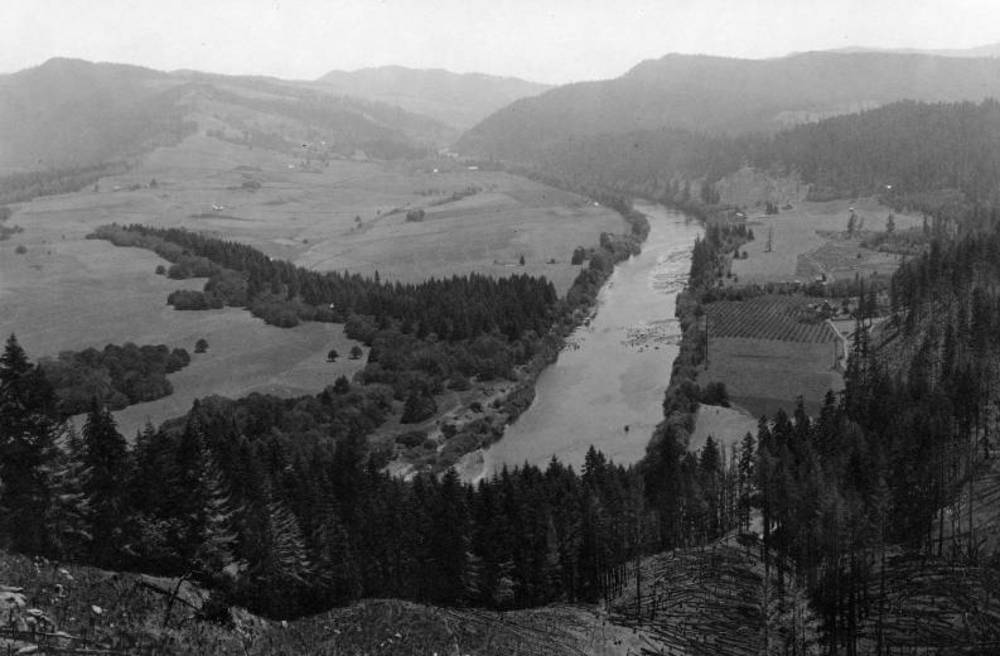

![Umpqua River]()

Umpqua River

The Umpqua River, approximately 111 miles long, is a principal river of…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Barbour, Barton. Jedediah Smith: No Ordinary Mountain Man. University of Oklahoma Press, 2009.