In the history of the North American fur trade, only the mountain man rivals the voyageur in myth, romance, and folklore. Beyond the singing, storytelling, and colorful appearance most often associated with voyageurs, their lives were among the most physically and mentally demanding of the era.

Some have applied the term voyageur to any boatmen of the fur trade era in North America, largely those of French Canadian ethnicity. More recently, historians have used labor status to define voyageurs as contracted servants (engagés) of fur-trading companies. In the strict organizational structure of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), the term voyageur defined one of four general classes of employee, ranking hierarchically below the gentleman and tradesman classes but above the laboring class. The voyageur class included several subclasses of employees, including interpreters, guides, steersmen (derrière), bowsmen (devant), and middlemen (milieu). Each voyageur signed a contract to work for a specific period of time and for an established wage.

As skilled boatmen responsible for safely transporting both people and goods up and down rivers, lakes, and overland stretches known as portages, voyageurs played an integral part in EuroAmerican exploration in the Oregon Country. They provided their skills to seminal colonial efforts, including the Lewis and Clark Expedition, Astor’s American Fur Company experiment, David Thompson’s journeys on the Columbia River, and the establishment of HBC trade centers such as Fort Vancouver. They were also often multi-purposed as trappers.

Through this psychologically trying and physically exhausting work, voyageurs became intimate with the landscape and resources of the Oregon Country. They gave Western names to—or had named for them—geographic landmarks such as The Dalles, where they employed a French term for "sluice" to describe the unique erosion effect of the rapid Columbia River flows on the volcanic rock in the area of today's eponymous Wasco County seat.

While many of the prevailing fur trade gentleman class were of British birth or otherwise connected, the voyageur class was marked by its ethnic diversity. Those of French Canadian and Métis heritage dominated the class, with many voyageurs establishing fur-trade relationships a la façon du pays (after the fashion of the country) with Native women from western tribal groups. Many voyageurs in the Oregon Country were also of Iroquois and Native Hawaiian ancestry. According to trapper and explorer Peter Skene Ogden, Oregon’s Owyhee River earned its name following the death of several Hawaiians tasked with trapping furs in the area.

In 1834 and 1835, voyageurs and others at Fort Vancouver, HBC’s headquarters and depot, requested that Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin petition for the assignment of Catholic priests to the Oregon Country. Retired voyageurs subsequently helped construct the first St. Paul’s church at French Prairie, completed in time for the arrival in 1838 of Frs. F.N. Blanchet and Modeste Demers.

During the same period, voyageurs who were retiring from the company sought authorization from McLoughlin and the HBC to remain in the Willamette Valley in lieu of receiving free passage to their place of origin. HBC voyageurs such as Andre Longtain (c. 1835) and Michel Laframboise (c. 1840) were attracted to the valley, especially near Campement de Sable, or Champoeg. Seasonal trading posts had been established in the Willamette Valley since the winter of 1812-1813, and retired Pacific Fur Company voyageurs, including Joseph Gervais and Etienne Lucier, had been living there since 1821. By 1844, many voyageurs had married local American Indian women and the population of French Canadian families in the area known as French Prairie had exploded to nearly 600 people.

Gervais hosted one of the earliest community meetings linked to establishing a government for Oregon. Despite challenges presented by the growing American population, other retired voyagers and their descendants helped Oregon establish a provisional government and organize as a United States territory and state. Some of today’s Oregonians still trace their roots to the region’s earliest voyageurs.

-

![]()

Champoeg, sketch by George Gibbs, 1851.

Courtesy Oregon Hist. Soc. Research Lib., 002924

-

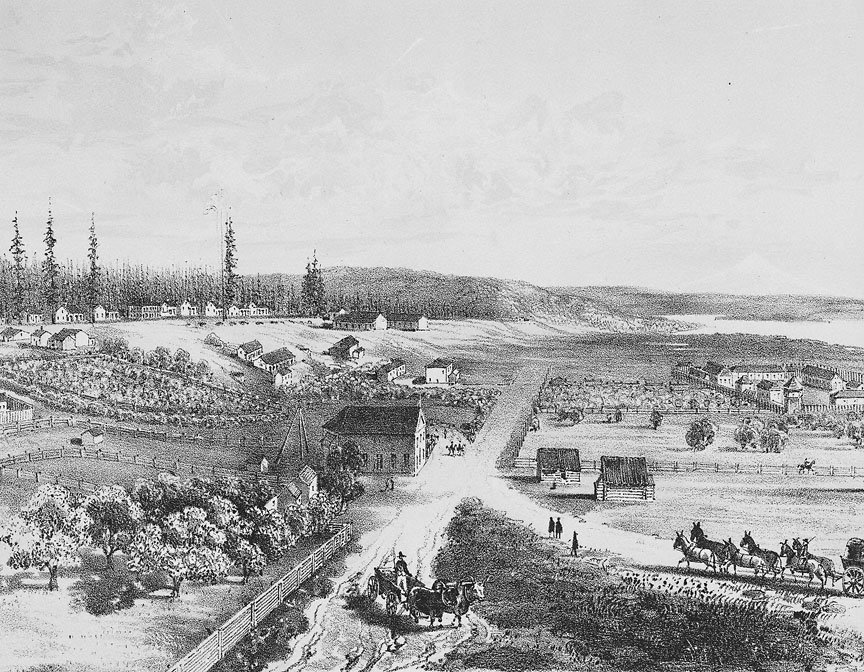

![Sketch of Fort Vancouver by H.J. Warre, c. 1845]()

Sketch of Fort Vancouver by H.J. Warre, c. 1845.

Sketch of Fort Vancouver by H.J. Warre, c. 1845 Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Lib., OrHi83437

-

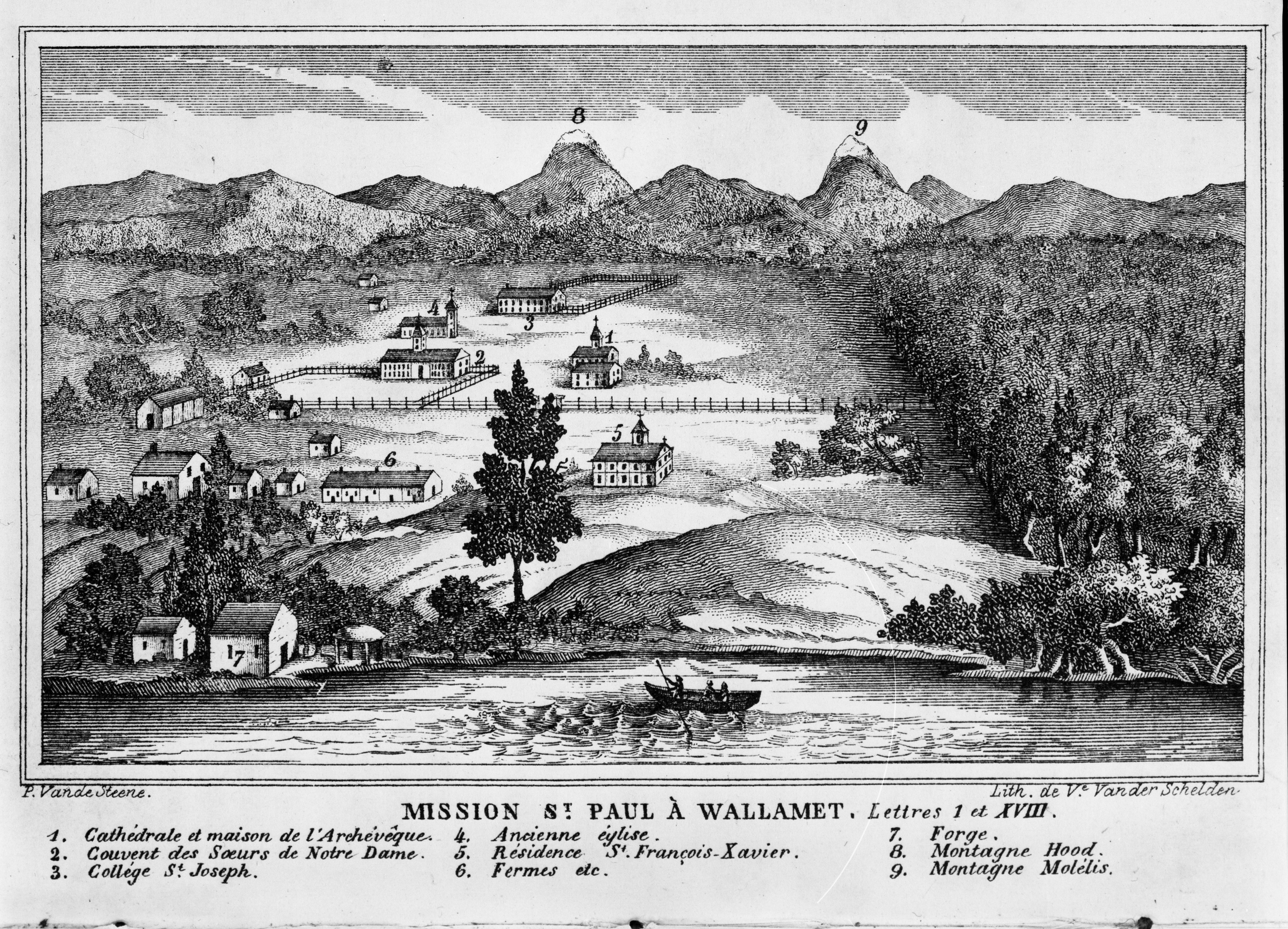

![Lithograph of Saint Paul Mission on the Willamette, 1848.]()

St. Paul Mission, lithograph of, 1848, bb003990.

Lithograph of Saint Paul Mission on the Willamette, 1848. "Saint Paul Mission on the Willamette," p. 50, courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Libr., bb003990

-

![]()

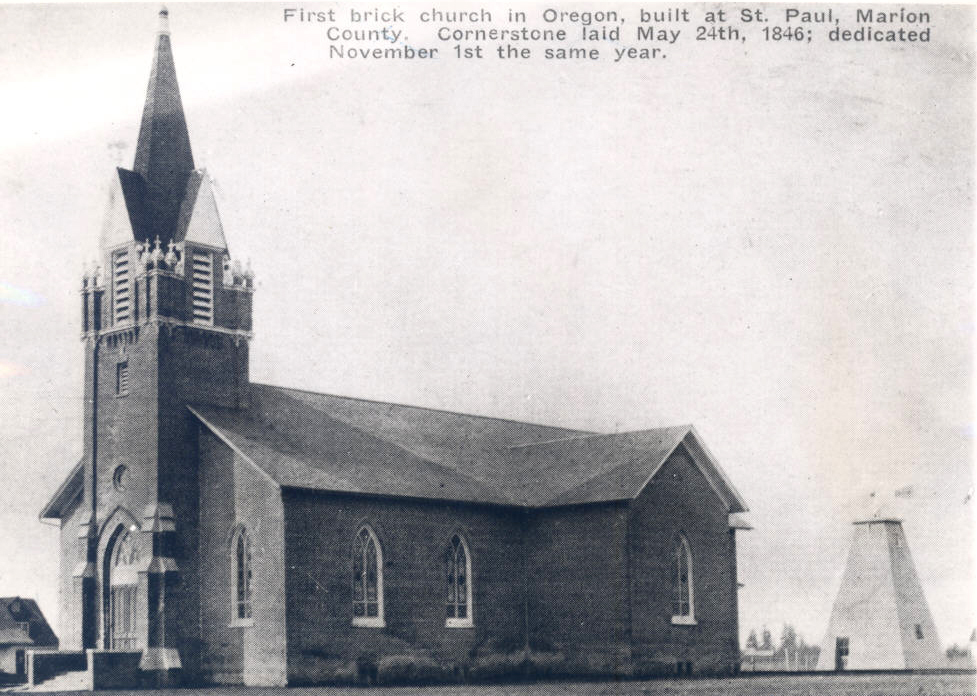

St. Paul Roman Catholic Church.

Courtesy Oreg. Hist. Soc. Research Library, 984d158

Related Entries

-

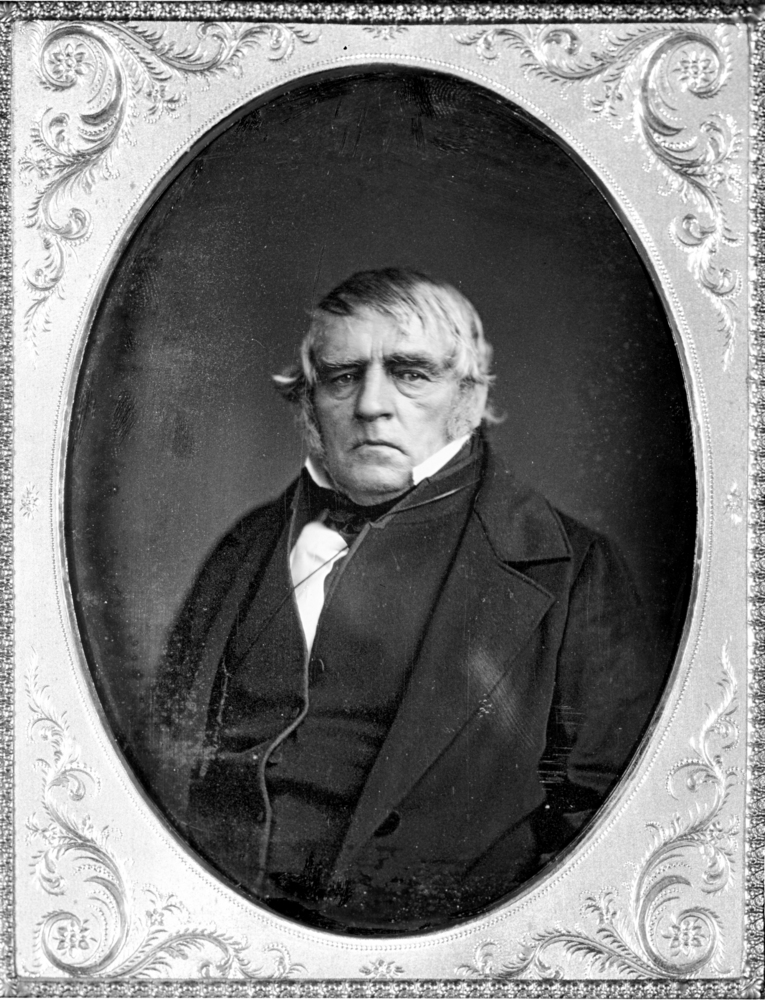

![Etienne Lucier (1793-1853)]()

Etienne Lucier (1793-1853)

Etienne Lucier, one of the first French Canadians to settle in the mid-…

-

![Fort Vancouver]()

Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver, a British fur trading post built in 1824 to optimize th…

-

![French Prairie]()

French Prairie

Located in Oregon's mid-Willamette Valley, French Prairie was resettled…

-

![Fur Trade in Oregon Country]()

Fur Trade in Oregon Country

The fur trade was the earliest and longest-enduring economic enterprise…

-

![Hawaiians in the Oregon Country]()

Hawaiians in the Oregon Country

Native Hawaiians were among the earliest outsiders in present-day Orego…

-

![Hudson's Bay Company]()

Hudson's Bay Company

Although a late arrival to the Oregon Country fur trade, for nearly two…

-

![Joseph Gervais (1777-1861)]()

Joseph Gervais (1777-1861)

Joseph Gervais was a prominent French Canadian settler in the Willamett…

-

![Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)]()

Peter Skene Ogden (1790-1854)

More than any other figure during the years of the Pacific Northwest's …

-

![Provisional Government]()

Provisional Government

The Provisional Government, created in May-July 1843, was the first gov…

-

![St. Paul Roman Catholic Church]()

St. Paul Roman Catholic Church

The St. Paul Roman Catholic Church was established in the mid-Willamett…

Related Historical Records

Map This on the Oregon History WayFinder

The Oregon History Wayfinder is an interactive map that identifies significant places, people, and events in Oregon history.

Further Reading

Mackie, Richard Somerset. Trading Beyond the Mountains: The British Fur Trade on the Pacific, 1793-1843. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1997.

Podruchny, Carolyn. Making the Voyageur World: Travelers and Traders in the North American Fur Trade. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

Shine, Gregory P. "Historical Background for Interpreting Village Houses 1 & 2." In Interpretation in the Fort Vancouver Village. Vancouver Wash.: National Park Service, 2010.